Introduction

Context of Inquiry

Researchers such as Harry (2008) and Bruder (1998) have highlighted the importance of family involvement in early intervention (EI). They say that the participation of parents in EI is vital in making sure that children have the necessary support needed in their education (Harry, 2008; Bruder, 1998). Families that are involved in early childhood education are also able to understand the link between what children learn at school and what happens at home (Friend & Cook, 2003).

Studies have also pointed out that the relationship between school and homework is critical in promoting further learning and is an integral part of their overall development (Friend & Cook, 2003). The current study is linked to this assertion because it contains an investigation of the perceptions of parents towards collaboration with education professionals in EI.

The findings of this study will help to extend early childhood education activities beyond the classroom. This way, children can have a more positive learning experience both at home and in the classroom. In addition, the contents of the study will be useful in helping parents to understand their children’s competencies and deficiencies in EI, thereby putting them in a strategic position of improving their confidence and learning abilities.

Indeed, by understanding the perception of parents towards collaboration with education professionals, the gap that exists in parent-teacher collaboration will be minimized because the lack of synergy between both parties in EI has been of significant concern (Friend & Cook, 2003; Harry, 2008; Bruder, 1998). Therefore, the current study will provide a basis for which teachers would better engage parents in EI because by understanding how to communicate or engage parents, teachers would be in a powerful position of positively influencing the learning environment for children with special needs.

Purpose of the study

The purpose of this study is to investigate the perceptions of parents towards collaboration with education professionals in EI. Scholars say that collaboration between different education stakeholders portends several positive effects on children with special needs (Trivette, Dunst, & Hamby, 2010). For example, these collaborative practices enable parents to develop parenting strategies that would improve the education outcomes of their children (Karst & Van Hecke, 2012). Notably, when parents and education professionals collaborate in EI, they are likely to understand children’s’ weaknesses and strengths and formulate strategies that would address pertinent issues in the learning environment (Dempsey & Keen, 2008).

Rationale for the Study

It is important to examine the role that collaboration plays in supporting successful early intervention because the law requires that parents and teachers should work together to improve children’s educational outcomes (McKenzie, 2009). For example, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) outlines the rights of teachers and parents in the education setting (Viviani, 2016).

However, collaboration between teachers and parents is not only encouraged because of this legal requirement but also because it is the right thing to do. Indeed, it is important to examine the role that collaboration plays in supporting successful early intervention because it helps to build a community of caring individuals who intend to support the educational achievement of children with special needs (Sayeski, 2009). Through this framework, it is possible to integrate the input of different types of education stakeholders in EI (Robinson & Buly, 2007).

The role of parental involvement in successful early intervention is further supported by research studies, which highlight the important role played by parents in improving education standards in the society (Shonkoff & Meisels, 2000; Friend & Cook, 2000). For example, Robinson and Buly (2007) suggest that parents are the single-most powerful catalytic factor for improving education standards of children with disability. Relative to this view, promoting collaboration between parents and teachers has many advantages linked with improved educational outcomes, such as a low dropout rate, improved test scores and high levels of self-esteem among children with special needs (Goddard & Goddard, 2007).

Significance of the Study and Research Gap

Research gap

Given the increased attention early education experts have given to collaboration in the inclusive learning environment, it is important to investigate the perception of families towards collaboration with education professionals in special education. As noted above, a research gap exists due to the failure of existing research to investigate the effects of cultural, social, and legislative factors on parents’ perceptions of collaboration in early intervention in special education in Saudi Arabia. However, most past studies have focused on investigating teachers’ perceptions regarding collaboration in early intervention with little focus on family’s perception regarding EI.

This preconception in research means that the evidence on collaboration in EI is biased towards only highlighting the professional view of collaboration in special education because past studies have mostly focused on investigating teachers’ perceptions towards collaboration. Consequently, this gap in the literature has made it difficult to address the contribution of families towards the practice as a strategy of improving the learning outcomes of preschool children with special needs.

This biased representation of collaboration has continued to characterize academic literature on collaboration in EI (Brownell, Ross, Colón, & McCallum, 2005) despite the existence of evidence showing the important role of families in supporting children’s learning development.

In addition, most of the empirical investigations involving collaboration between family members and professionals in early childhood special education are based in the United States. Therefore, we do not know the experiences and perceptions of parents in non-western countries, such as Saudi Arabia regarding collaboration in early childhood education. Indeed, the literature is almost silent on how parents or families in non-western countries perceive collaboration in the inclusive learning environment or how their cultures influence the quality of partnerships among education stakeholders in early childhood education.

In addition, no study has explored the perception of family members towards collaboration for children with special needs who are between 0 to six years old in Saudi Arabia. Consequently, there is a clear gap in the literature, which is centered on understanding how parents in Saudi Arabia view collaboration with education professionals for special education children below six years of age. The current study will address this gap to provide a balanced and holistic view of collaboration in EI. To fill this gap, the proposed study will focus on investigating families’ perceptions of collaboration in early childhood development in Saudi Arabia. The significance of this investigation appears below.

Significance of study

Although Saudi Arabia has been credited for making significant gains in promoting collaboration and inclusivity in its education sector (Murry & Alqahtani, 2015), authorities still need to do more to further inclusion efforts and support collaboration in the country’s educational system. This finding justifies the need to undertake the proposed study because there are concerns about the effects of segregation on the educational progress of children with disabilities in the kingdom. Such concerns could be partly rooted in the perceptions of families towards collaboration. This concern underscores the need to review the role of families towards collaboration with other stakeholders in early childhood education.

The aim of the proposed study is to understand the perceptions of families in Saudi Arabia towards collaboration with professionals in early childhood special education. Relative to this aim, the investigation will be in two parts. The first one will explore quantitative issues relating to the research aim. Here, three key areas of research will guide this study. The first one focuses on understanding the current trends in the perception of Saudi Arabian families towards collaboration in early childhood development. This area of research seeks to establish current patterns of engagement between families and professionals in EI.

Based on this understanding, it will be possible to comprehend their perceptions towards collaboration. The second area of analysis that will be investigated in this study will focus on the potential barriers that exist between Saudi families and professionals in early childhood education. Lastly, this study will seek to find out whether demographical differences among Saudi families affect their perception of collaboration in early childhood development. Collectively, these issues will form the framework for the quantitative part of the investigation.

The second part of the study will investigate qualitative issues relating to the research aim. Here, three key issues will be investigated as well. The first one centers on investigating the influence of cultural factors and communication styles in understanding the perceptions of Saudi Arabian parents towards collaboration in early childhood intervention. Comparatively, the second part of the investigation will focus on understanding factors that promote collaboration between families and professionals in early intervention services in Saudi Arabia. The last area of investigation for the qualitative research part will explore the main issues that hinder parents’ collaboration with professionals in early intervention services in Saudi Arabia. A list of the research aim and questions appears below.

Research Aim

To understand the perceptions of families in Saudi Arabia towards collaboration with professionals in early childhood special education

Research Questions

Quantitative questions

- What are the natural trends of Saudi Arabian parents’ current perceptions of collaboration with professionals in early intervention?

- What are the potential barriers to Saudi Arabian parents collaborating in the delivery of early intervention services?

- Are there significant differences in Saudi Arabian parents’ perceptions of collaboration across demographic differences in the population?

Qualitative questions

- What are the perceptions of Saudi Arabian parents regarding collaboration with professionals? What are the effects of cultural influences on Saudi parents’ collaboration with professionals? What communication methods are most effective for use in early intervention services in Saudi Arabia?

- What factors promote parents’ collaboration with professionals in early intervention services in Saudi Arabia?

- What factors hinder parents’ collaboration with professionals in early intervention services in Saudi Arabia?

Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework of this study will be useful in explaining, predicting and understanding the research phenomenon. It could also help in extending the knowledge characterizing the perceptions of families regarding collaboration with professionals in early childhood development. The framework will also demonstrate how collaboration extends to the broader area of research that will be investigated in this study. Based on these findings, the researcher will use the community of practice (COP) theory as the main theoretical framework for the proposed study.

The model proposes elements of collaborative learning among different educations stakeholders to solve problems or create projects that appeal to shared interests and goals (Wenger, 1998). The COP theory addresses different issues in collaboration such as social interactions, team dynamics, and education planning. It helps to address issues of common interest through collaborate over an extended period by addressing issues and challenges associated with the achievement of common goals in EI special education (Wenger, 1998). Wenger (1998) also describes three dimensions of the model as joint enterprise, shared repertoire, and mutual engagement. He argues that these elements interact within a broader framework of collaboration that defines COP development (Wenger, 1998).

The COP theory, which will be used in this study, stems from a broader group of concepts and principles in collaboration linked with family-centered practices. A family-centered practice is a collaborative approach in education that enables family members to support and protect their children across multiple service systems (Bamm & Rosenbaum, 2008). Family-centered practices are based on the idea that education professionals should treat parents with respect using individualized, flexible, and effective teaching practices (Dunst, 2002).

Family-centered practices also emphasize the need for education stakeholders to share information so that parents can make informed decisions about their children’s’ educational development and achieve desired goals based their children’s needs (Bamm & Rosenbaum, 2008). Family-centered practices also stress the importance of child safety within family or community settings, while building on existing social networks to achieve optimal outcomes (Bamm & Rosenbaum, 2008).

In this study, families of children with special needs are the primary focus of the study because the proposed investigation aims to investigate their perceptions towards collaboration. Therefore, when they get help to develop flexible and effective practices, they are better able to support their children at home and school (Dunst, 2002). Within this framework, professionals can also help families to participate in collaboration when delivering services to their children, based on family dynamics and children’s unique needs.

The COP theory also shares a link with Bronfenbrenner’s (1992) bioecological systems theory, which suggests that a person’s development is impacted by their interaction with the environment. Here, the environment is reviewed by investigating five different terms. The first one is the micro-system, which focuses on relationships between individuals and interactions with the immediate living environment (Jaeger, 2016). The second one is the mesosystem, which focuses on evaluating interactions between different parts of the microsystem (Bronfenbrenner, 1992). For example, it could investigate the relationship between a child’s parents and educators.

Exosystem is the third term used in the bioecological systems theory. It refers to relationships between different parts of the microsystem, which do not directly influence a person’s development (Vélez-Agosto, Soto-Crespo, Vizcarrondo-Oppenheimer, Vega-Molina, & Coll, 2017). Another tenet of the theory is the macrosystem, which focuses on understanding how people’s cultural and social norms affect their behaviors and developmental growth patterns.

Lastly, chronosystem is the last tenet of the bioecological systems theory and it refers to the events and transitions in one’s environment, which take place throughout one’s life (Jaeger, 2016). Based on these findings, collaboration between parents and professionals occurs within the mesosystem because it allows the researcher to understand how the quality of the partnership influences children’s outcomes in early intervention.

Despite the link between the bioecological systems theory, family-centered practices, and the COP theory, the latter forms the theoretical framework for this study. The justification for choosing this theoretical framework is based on different categories of education stakeholders that can be involved in COP development for several reasons including “sharing historical roots, having related enterprises, facing similar conditions, sharing artifacts, and competing for the same resources (Wenger, 1998, p.127). From this perspective, families can work with education professionals to address the needs of children with special needs.

The Cop theory also provides a model for understanding how to improve their practices in a variety of settings, such as homes, schools, or other natural environments in the community. Overall, the COP theory will help the researcher to frame how families and professionals could foster collaboration in EI by pursuing shared goals that are centered on improving the learning outcomes of children with special needs.

Definition of Terms

Early intervention (Early Childhood in Special Education) – Early intervention means taking precaution to address a child’s educational and developmental needs in the learning environment. This type of service should provide support to families or parents of children who are in their preschool years to identify key strengths and weaknesses that affect their children’s’ educational development. Family members may receive several types of support. Some of them include therapy, counseling, and universal health services (among others) (Bruder, 2010).

Collaboration – Collaboration in early intervention refers to a model where two or more parties involved in a child’s education come together and create positive outcomes that are otherwise unattainable if one of the parties was acting alone (Tzivinikou, 2015). Usually, collaboration allows stakeholders to work together by addressing the learning challenges affecting children. This process gives them room to look for new means of creating a positive working environment for children with special needs (Tzivinikou, 2015).

Parents of children with special needs – Parents of children with special needs refer to a group of people who exercise parental rights on pre-school children with special needs (Bruder & Bologna, 1993). These people may be biological parents or guardians but in some cases, caretakers could also fit this description (Golya& McIntyre, 2018).

Professionals of children with special needs – Professionals of children with special needs are people who are certified early intervention specialists. Their work is to provide education services to children with special needs. These people often have educational, academic, or professional qualifications to do their work (Robinson & Buly, 2007). For example, a person with a Master’s degree in special education and provides services that are in line with the profession fit this description. Based on this understanding, there are different kinds of professionals for young children with special needs. Some of them include teachers, therapists, speech language professionals, and principals (Robinson & Buly, 2007).

Literature Review

Introduction

This second part of the study will investigate what other researchers have said about the current research topic. However, before delving into the details of this analysis, it is important to restate that this investigation will help to operationalize the legal requirement guiding collaboration between families and professionals in early childhood development in Saudi Arabia. As highlighted in the first chapter of this report, different jurisdictions have unique laws that govern how teachers and parents should collaborate in early childhood development. For example, reference was made to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), which outlines the rights of teachers and parents when collaborating in the education setting.

However, the importance of undertaking this review is not limited to fulfilling legal responsibilities of education stakeholders because the researcher recognizes that investigating the perceptions of families towards collaboration with education professionals in EI is the right thing to do. In other words, this study will help to build a community of caring individuals who intend to support the educational achievement of preschool children.

The overriding framework that supports the implementation of this research plan is also instrumental in promoting collaboration of all stakeholders and not only families and professionals in early childhood education. Therefore, this study will be instrumental in integrating the input of different types of stakeholders in EI. The important role of promoting stakeholder integration in EI is supported by research studies, which highlight the significance of families in improving education standards in the society (Brownell, Adams, Sindelar, Waldron, & Vanhover, 2006).

Through the development of a reliable framework for increasing collaboration between education stakeholders in EI, there is likely to be a low dropout rate, improved test scores and high levels of self-esteem for children with special needs (Goddard & Goddard, 2007). Although the benefits of undertaking this study are succinctly highlighted, it is essential to understand early intervention and its importance to the educational development of children with special needs.

What Is Early Intervention and Why Is It Important?

According to Bruder (2010), early intervention means taking precaution to address a child’s educational and developmental needs early in the child’s life to provide room for teachers or parents to take remedial action if there is a need to do so. This type of service is aimed at providing the necessary support for families or parents of children who are in their preschool years to improve their children’s learning outcomes. Such types of support may include therapy, counseling, or even universal health services (Brownell et al., 2006).

Early intervention is important because it plays a role in the future development of a child. Indeed, according to two scholars, Marilyn Friend and Jean Ann Summers (as cited in Bruder 2010), the first five years of a child’s life are important to their neurological and brain development. The importance of this growth phase in their lives is underscored by the sensitivity of a child’s cognitive development process to their daily experiences in the school setting (Bruder, 2010).

Therefore, it is not enough for children to be exposed to a good environment at school because the home environment is also critical for their development (Lim, 2015). Consequently, there needs to be a collaborative framework between education professionals and families if they are to create a good environment for children to learn (both within and out of school).

Experts suggest that parents or teachers should address developmental delays early in a child’s life before it gets worse and affects other areas of their development (Macfarlane & Lakhani, 2015). This recommendation is the essence of early intervention because it encourages families and teachers of preschool children to introduce the right interventions early in a child’s life to provide the best kind of environment for education development (Whitbread, Bruder, Fleming, & Park, 2007). Indeed, when early intervention is introduced in EI, children could easily meet their learning goals at a time when their minds are receptive to new knowledge. Therefore, early intervention can have a significant impact on a child’s developmental trajectory.

Researchers such as Whitbread et al. (2007) have highlighted the importance of family involvement in early childhood intervention. They say that parental involvement in education is critical, in making sure that children have the necessary support in learning (Whitbread et al., 2007). Families that are involved in early childhood education understand the link that exists between what the children learn at school and what happens at home. Studies have also pointed out that the link between the school and home environment is critical in promoting learning and is an integral part of children’s overall development (Goddard & Goddard, 2007; Whitbread et al., 2007).

The current study plugs into the link between the school and work environments by contributing to the availability of resources that children need in early childhood intervention. Therefore, it will help to extent early childhood education activities beyond the classroom. This way, children can have a more positive experience learning both at home and at school. Consequently, the findings of this study will be useful in helping parents to understand their children’s competencies and deficiencies, which puts them in a strategic position of helping them to improve their confidence and learning abilities.

Collaboration will also help to minimize the gap between families and teachers, because the lack of synergy between both parties in EI has been of significant concern to stakeholders. Therefore, the current study will provide a basis for which teachers would better engage parents in EI development. Therefore, by understanding how to communicate or engage with parents in the inclusive learning environment, teachers would be in a powerful position of positively influencing the learning environment.

An Overview of Early Intervention Services in Saudi Arabia for Children who are below Six Years

Despite the existence of variations in how professionals in the education sector implement their teaching styles, there is a consensus that early childhood education helps to prepare children for success both in their academic and personal lives (Aldabas, 2015; Harry, 2008; Bruder, 1998). This principle is also applicable to the Saudi Arabian education system because education authorities in the country consider early childhood education for children aged between 0 and 6 years as important (Aldabas, 2015). Indeed, it is a common Saudi culture to respect the educational growth of children because they are the future of the society.

The progress made in promoting the development of early intervention in Saudi Arabia within the last five decades have been broadly influenced by different social, religious, historical and economic issues (Rabaah, Doaa, & Asma, 2016). Notably, The government of Saudi Arabia has taken a proactive role in making sure children within this age group get the best education services (Rabaah et al., 2016). It has also developed policies that facilitate the provision of education services for children with special needs (Rabaah et al., 2016).

The provision of early childhood education for preschool children in Saudi Arabia started in the 1970s (Rabaah et al., 2016). The establishment of additional classrooms attached to the general education environment characterized the introductory phase of this growth (Rabaah et al., 2016). The Saudi Arabian Ministry of education is mandated to develop policies that guide the provision of education services for preschool children (Murry & Alqahtani, 2015). The ministry also provides education services to children with special needs who fall within this age group (Murry & Alqahtani, 2015). Children who have severe disabilities often receive education services in private educational facilities, while those who have mild cognitive disabilities learn in inclusive environments (Aldabas, 2015).

The provision of special education services in Saudi Arabia was mostly spearheaded by communities who advocated for the establishment of special education schools that totally or partially integrated children with special needs in the mainstream educational setting (Rabaah et al., 2016). Total integration was implemented through the construction of special education classes that were linked to regular school programs (Al-Zoubi & Rahman, 2015). Therefore, resource use programs were used to facilitate integration. Counselor and teacher programs also helped to facilitate integration in the education setting.

When a review of the Saudi Arabian educational curriculum used for children with disabilities was undertaken, it emerged that past curricula was significantly underdeveloped (Al-Zoubi & Rahman, 2015).

This is because teachers had the freedom to structure the curriculum whichever way they wanted and it brought inconsistencies in the assessment of educational outcomes. However, after the government mainstreamed the country’s educational practices, this practice was abolished and a mainstream educational curriculum that was premised on education theory and best practices was developed (Rabaah et al., 2016; Al-Zoubi & Rahman, 2015). Today, Saudi Arabia offers age-appropriate education services that reflect international standards in the field.

According to the Saudi Arabian government guidelines, the educational curriculum offered to preschool children today is premised on three goals (Murry & Alqahtani, 2015). The first one is to direct the educational services of children by giving them opportunities to improve sensory development and maintain a robust physical growth (Murry & Alqahtani, 2015). The second objective is to encourage children to collaborate with one another and enjoy being in the presence of their peers (Murry & Alqahtani, 2015).

The third objective is to make sure that the students get the best opportunities for optimum mental, moral, and physical growth (Murry & Alqahtani, 2015). In this framework, current educational guidelines encourage educators to prepare children for environmental factors that characterize elementary school settings (Rabaah et al., 2016; Al-Zoubi & Rahman, 2015). This guideline encourages teachers to teach age-appropriate learning content and promote the development of social skills and language among preschool children.

Importance and Outcomes of Family Involvement in Early Intervention Special Education Programs

Many researchers have investigated the need for family involvement in education (Sabol, Sommer, Sanchez, & Busby, 2018; Bruder, 1998). Relative to this assertion, Bruder (2010) highlights the need for parental involvement across all stages of learning and age groups (not only among preschool children). In other words, the higher the level of engagement between families and educators, the more children are likely to benefit from a positive learning environment, which will ultimately boost their learning outcomes (Bruder, 2010).

Nonetheless, family engagement in early intervention could take different forms and it is essential for all stakeholders to understand these variations and their influence on children’s educational outcomes. Relative to this assertion, studies have shown that the beliefs held by educators about family involvement are likely to affect the quality of relationships that will be forged between family members and education professionals (Simpson & Envy, 2015).

The involvement of family members in their children’s education is associated with several positive outcomes including low levels of absenteeism, increased concentration of children in their class work, and improved educational performance (Simpson & Envy, 2015). Several research articles have supported this analogy by pointing out that children who experience adequate family involvement in their educational experience benefit from improved social skills and behaviors (Idol, Nevin, & Paolucci-Whitcomb, 2000; Simpson & Envy, 2015; Friend & Cook, 2003; Harry, 2008; Bruder, 1998).

They also earn higher grades and test scores compared to their counterparts who do not get the same quality of education (Simpson & Envy, 2015). The benefits of parental involvement in education services has also been highlighted by researchers, such as Bailey, Simeonsson, Yoder, and Huntington (1990), who say that parents tend to have a higher level of confidence regarding their children’s education system if they are involved in it. Notably, studies have also shown that a strong involvement of family members in their children’s education could lead to improved physical and academic performance (Bailey et al., 1990).

These positive attributes are realized through increased academic focus, which is associated with children who enjoy high levels of collaboration between their teachers and family members. Different countries recognize this fact. Consequently, they have anchored the need for parents and teachers to collaborate in law. Current legislations that guide how education professionals and family members collaborate in America and Saudi Arabia are discussed below.

Current Legislation That Involve the Families in Educational Process

As highlighted in this document, collaboration among different stakeholders in early childhood education is partly supported by legislative policies, which provide a framework of engagement for family members and education professionals in EI. One of the first attempts at legalizing collaboration between families and education professionals happened in the US in 1975 through the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (Hernandez, 2013).

This piece of legislation required American schools to provide free education services to children who had special needs (Hernandez, 2013). Such legislative advancements were premised on the understanding that collaboration among education stakeholders was one of the best practices in the special education field. In line with this vision, special educators and related service providers were required to take part in the implementation of Individualized education plans (Hernandez, 2013).

The legal focus on pre-school children only happened in the 1990s when the theme of collaboration extended to education professionals who provided associated services to children aged between 0 and 3 years (Hernandez, 2013). The most recent evolution of this legislative piece happened through the IDEA, which does not make open reference to collaboration but encourages education professionals to collaborate across different levels of teaching (mostly between general and special education teaching) (Pugach, Blanton, & Correa, 2011; Paulsen, 2008).

Here, researchers say that different education agencies also contributed to the advancement of the collaborative spirit among education stakeholders in America (Hernandez, 2013). For example, the Council of Exceptional Children (CEC) incorporated collaboration as part of its operational standards because of the national movement towards providing holistic education in the US (Hernandez, 2013).

It is through the involvement of such organizations that the role of collaboration between family members and education professionals has been highlighted or emphasized in the legal framework of education service provision in the US. For example, the CEC underscores the need for education professionals to collaborate with family members in a culturally appropriate manner (Hernandez, 2013). The conversation has been extended further to emphasize the need for hiring teachers or education professionals who have collaborative skills in special education (Pugach et al., 2011).

This need was emphasized after it was established that professionals from related skills may not understand how to collaborate with families in the special education setting (Paulsen, 2008). Nonetheless, the legislation of collaborative practices in early intervention has created a new culture of separating roles among different education professionals (Pugach et al., 2011). The unique culture was developed from the understanding that collaboration with family members would create a new culture because education stakeholders would be operating in a different setting from the one where the children’s peers were present (Hernandez, 2013).

The progress made in legislating collaboration between family members and education professionals in the US has significantly contributed to a strict adherence to educational policies that support collaboration in the special education sector (Pugach et al., 2011). The 2004 changes made to the IDEA are the most relevant pieces of legislation in understanding the legislative progress that has been made in the education sector to support collaboration between different stakeholder groups.

Notably, the law has unique parts that guide how families should be involved in collaborative processes. For example, Part C of the legislation requires parents to be involved in their children’s transition plan (Pam, 2017). This provision is articulated in Section 303.209 of the Act (Pam, 2017). The law also requires the lead agencies involved in the early intervention to notify parents about eligibility discrepancies for children who are covered under the Act (Yell, 2019). Here, the goal is to allow parents to dispute findings, especially if their children are found not to meet the eligibility criteria of children with disability.

Part C of IDEA also requires leading educational agencies to notify parents about their rights when their children are referred to Part C of the law (Yell, 2019). This provision is outlined in confidentiality provisions of the law that require participating agencies to comply with maintenance retention and storage policies (Pam, 2017). The IDEA also mandates education professionals to comply with a request from a family member to review any records about early intervention, at least within 10 days after such a request is made (Pam, 2017).

Through such requests, the leading agencies may provide parents with evaluation reports or assessment documents of the child’s educational records. Lastly, the law also requires education professionals to seek the consent of parents before divulging any personal information relating to their children in public documents (Yell, 2019). Broadly, the IDEA requires professionals in the education system to nurture a spirit of collaboration with family members.

In Saudi Arabia, collaboration between families and education professionals is also encouraged in law but there are no specific legal provisions outlining how the process should occur. Instead, most of Saudi Arabian laws related to collaboration are focused on defining disabilities and integrating children with special needs in the mainstream education system (through partial or full integration). For example, the Regulations of Special Education Programs and Institutes (RSEPI) law stipulates these issues (Rotatori, Bakken, Obiakor, Burkhardt, & Sharma, 2014).

Therefore, the legal environment in Saudi Arabia has not evolved to outline how collaboration between parents and education professionals should occur. Nonetheless, the RSEPI outlines different rights and responsibilities of stakeholders in the provision of education services in Saudi Arabia (Rotatori et al., 2014).

Broadly, the findings highlighted in this document show that the US and Saudi Arabia both have legal provisions stipulating how special education services should be provided and the roles of different stakeholders in the process. The law contains specific provisions surrounding transition services, and a definition of important concepts in special education, such as disability, the least restrictive environment and transition services.

Least Restrictive Environment (LRE) in Early Intervention

The concept of the least restrictive environment comes from the understanding that children with special needs should receive education services in settings that are close to the mainstream education classroom (Blackmore, Aylward, & Grace, 2016). The concept also suggests that an appropriate educational program can be developed to help children make significant gains in their learning programs.

For many researchers, the concept of the LRE is synonymous with inclusion (Hamilton-Jones & Vail, 2014). In other quarters, it has been associated with the placement of children with special needs in the general education setting (Blackmore et al., 2016). Although not all types of children who have special needs learn in the mainstream educational classroom, LRE has made it possible for education professionals to provide instructions for children with varied disabilities (Friend, Cook, Hurley-Chamberlain, & Shamberger, 2010).

Family Needs in Early Intervention

To understand family needs in early intervention, it is important to comprehend the experiences of families in raising and educating children with special needs. According to Sukkar, Dunst, and Kirkby (2016), most families are under intense pressure and financial strain raising children with special needs. These pressures could lead to depression, anger, self-blame or even denial (Kyzar, Brady, Summers, Haines, & Turnbull, 2016).

These negative feelings may influence how well they collaborate with education professionals in the special education setting (Lam, 2014). Regardless, of these sentiments, Turnbull et al. (2007) encourage families to engage with teachers and care providers who understand their needs. However, evidence suggests that many education systems do not appeal to family needs (Sukkar et al., 2016).

According to Sukkar et al., (2016), families experience early intervention at different levels. The opportunities it creates are expected to offset the developmental limitations associated with children who have special needs. Family centered practices adopted in early intervention are predicated on competency-enhancing experiences (Dunst, Trivette, & Hamby, 2008). The goal of using them is to develop capacity-building and enhancing experiences (Dunst et al., 2008).

Nonetheless, the global or universal application of collaboration in early intervention is based on the attachment of family dynamics to a broader based ecological system of societal growth and development (Bronfenbrenner, 2005). The nature of these systems could either have development-enhancing or development-impeding experiences for those involved (Bronfenbrenner, 1992).

One of the biggest challenges early childhood educators have with collaboration is the development of support systems that would aid collaborative relationships. Although family-centered collaborative practices have universal applicability (Dunst, Trivette, & Hamby, 2006), their application to EI have not received widespread support. Regardless of these challenges, family-centered collaborative practices are largely deemed as necessary inputs of preparing families to manage the reaction and challenges of educating children with special needs (Sukkar et al., 2016).

Indeed, when families and education professionals collaborate effectively, there is likely to be better responsiveness to family and cultural values, which would have long-term positive effects on children with special needs (Sukkar et al., 2016). For example, in a study authored by Cameron and Kovac (2017), it was established that collaboration helped to minimize bullying incidents among pre-school children.

Role of Collaboration between Parents and Teachers

The role of collaboration between parents and teacher stems from the vital support that both educational stakeholders provide to children in early intervention. Indeed, as highlighted in this document, when parents and teachers collaborate effectively, they are likely to have a long-term impact on the educational achievement standards of children with special needs. Collaboration between both parties plays a vital role in empowering children to improve their learning outcomes and adopt better social behaviors (Sukkar et al., 2016).

In this regard, collaboration encourages teachers to open up their lines of communication and let parents know what is happening in the classroom and how learning about their children’s educational progress could aid their work. In this regard, collaboration allows teachers to share what is happening in the classroom by involving families in their activities and projects. They can achieve significant progress in their work by tailoring their communication styles to their classroom environments (Sukkar et al., 2016).

Sukkar et al. (2016) add that one of the most significant roles played by collaboration is to provide education professionals with development opportunities because it expands the scope of their work and the visibility of their practices. For example, researchers have highlighted the role of training in promoting collaborative practices in early intervention (Stratigos & Fenech, 2018; Moss, 2015).

Such programs help education professionals to improve their skills because they learn new knowledge about communication styles, which they could use to engage with family members. From this analysis, the role of collaboration is partly enshrined in its ability to incorporate family involvement in the growth and developmental progress of education professionals (Stratigos & Fenech, 2018; Moss, 2015). Through the effective support of these communication plans, teachers learn of new pathways to achieve high levels of skills competency based on collaborative practices.

Collaboration between Families and Professionals

Collaboration between families and professionals has been highlighted in this literature review as an important strategy for the promotion of learning outcomes in early interventions. An attempt to understand the importance of collaboration between family members and professionals in early intervention requires a holistic comprehension of the concept. Different people perceive collaboration in unique ways, depending on their environmental influences.

However, a general overview of the concept suggests that it occurs when educational stakeholders work together to create interdependent professional relationships (Hernandez, 2013). Therefore, in the context of this study, collaboration refers to the act of working with someone else to fulfill a predetermined set of goals. If the concept is applied to families and professionals, it refers to how well people who have the legal custody of a child collaborate with education professionals who may include teachers, speech language professionals or even therapists.

Types of Collaboration

Collaboration may take different forms, based on the context of application or the preexisting legal environment. The most common types are discussed below.

Communication

Communication is an intrinsic part of what education professionals do in early intervention because they impart knowledge to children by speaking to them. The same strategy is used to foster collaborative practices with family members. In other words, education professionals could collaborate with family members through oral, written, and non-verbal communication messaging. In a study authored by Burnage (2018), it is established that communication is one of the most effective collaboration skills required in early intervention.

Home visits

One of the challenges associated with collaboration between education professionals and teachers is unequal schedules and time constraints because both sets of education stakeholders are juggling multiple responsibilities at the same time. Home visits are used in early intervention settings when there are discrepancies regarding parental follow-up of children with special needs. In other words, other collaborative frameworks may only involve the transfer of secondary information regarding what is being undertaken in schools or a simple phone call from a concerned parent or teacher regarding a child’s education progress.

Research studies have shown that home visits provide an affective form of collaboration between parents and teachers (Families and Schools Together, Inc., 2016). Such visits are often arranged when teachers want to develop personal relationships with parents or family members. Home visits are deemed some of the most fruitful collaborative engagements between education professionals and family members because they occur in informal environments where both parents and teachers can interact informally and share information about their children’s development which would otherwise not have been known if there was a formal communication structure (Families and Schools Together, Inc., 2016).

Through such visits, educational professionals can also learn more about the family values and goals of their students and even recommend ways in which their educational growth could be fostered at home (Families and Schools Together, Inc., 2016). The opposite is true because family members can also better understand their child’s teacher and support their work at an interpersonal level (Families and Schools Together, Inc., 2016).

Assessment reviews

Collaboration between education professionals and family members has also occurred through assessment reviews, which refer to the process of involving family members in assessment practices (Yell, 2019). In this type of collaborative framework, parents or family members are notified about their children’s progress and encouraged to make follow-ups at home to improve any areas of weaknesses (Yell, 2019).

The benefit of this kind of assessment method to parents is its tendency to inform family members about the education progress of their children (Yell, 2019). Therefore, they are aware of the strengths and weaknesses of their children’s education progress in a timely manner (Pam, 2017). This information enables them to understand how to help their children both at home and at school. Their contribution at schools could be broad and may include different activities, such as providing learning resources needed to support their children’s education, or simply showing up at schools to take part in assessment reviews (Pam, 2017).

At home, they could follow up on their children’s weak areas of learning that show up in the assessment process. Overall, their involvement in assessment reviews makes them aware of their children’s education development, thereby empowering them to support their growth and development.

Individualized family service plan (IFSP) meetings

IFSP refers to the development of an educational service plan for children with special needs (Special Education Guide, 2019). This tenet of education service provision is an important part of collaborative learning because it provides the framework through which education professionals and families can interact freely (Special Education Guide, 2019). For example, through the IFSP, parents can learn about the educational services their children will receive. Similarly, it allows family members to understand the current level of perception about their educational outcomes or the specific learning needs of their children (Special Education Guide, 2019).

Scholars such as Donald Bailey and Carol Trivette have demonstrated that family members can be integrated in such meetings to improve current levels of function in EI by adopting a family-based approach in decision-making (Shonkoff & Meisels, 2000). Involving parents in IFSP meetings would make sure the overall education program includes features that are supportive of family input. Therefore, collaboration between education professionals and family members in EI can be fostered by changing the makeup of people who take part in EI meetings.

Ideally, the main stakeholders in such meetings include physical therapists, occupational therapist and speech and language therapists (Special Education Guide, 2019). In some cases, a psychiatrist and neurologist are also involved in the process (Special Education Guide, 2019).

Data-based decision-making

Data-based decision-making can also occur as a type of collaborative framework because it centers on making joint decisions based on preexisting data regarding collaboration. According to McWilliam (2010), the data based decision-making method refers to the formulation of decisions regarding the educational achievement of children using assessment data. For a long time, teachers have been using this technique to inform instructional decision-making processes (Friend et al., 2010). Education professionals often rely on different kinds of data sources to make these decisions (McWilliam, 2010).

However, with the development of legal provisions surrounding the integration of children with special needs in the general education setting, the generation of data from standardized tests has emerged as a legal requirement in some jurisdictions (Friend et al., 2010).

The increase in accountability standards for educators has also increased the profile for data-driven decision-making (McWilliam, 2010). In the same breadth of analysis, it has become increasingly important for education professionals to make data-driven decisions (McWilliam, 2010). This need has been registered in collaboration literature because family members have also been included in making data-driven decisions about their children’s education (Friend et al., 2010; McWilliam, 2010).

Education professionals could use educational data to find out areas of strength or weakness regarding a child’s education and share the same findings with family members (Friend et al., 2010; McWilliam, 2010). At the same time, some researchers have shown that they could use the same data to examine their instructional practices and improve on the same field with the help of family contribution to the decision-making process (Singh & Zhang, 2018; Zhang, 2017).

The data-driven decision-making process could also be used to support formative assessment methods such as home work and teachers assessment techniques because families can provide a good environment both at school and at home to help their children to do home work based on a teacher’s recommendations and observations at school (Singh & Zhang, 2018; Zhang, 2017). Data-driven decision-making methods are also useful in supporting summative assessment processes, such as classroom tests and performance-based assessments, because they are useful in generating the data that will be used to share information with family members (Singh & Zhang, 2018; Zhang, 2017). These findings highlight the need to understand the benefits and challenges of collaboration.

Benefits and Challenges of Collaboration

Positive outcomes associated with collaboration between family and professional

Collaboration between families and education professionals has been hailed as a useful tool for helping children with disabilities to improve their learning outcomes (Friend & Cook, 2007). Some researchers deem collaboration between these two groups of education stakeholders as a best practice in special education (Epstein, 2001). Some education experts also view collaboration as an important tool for EI development because it provides a framework for education professionals to take up more responsibilities in the provision of special education services (Friend & Cook, 2007).

Indeed, collaboration between families and education professionals has been tied to the long-term success of children with special needs. Alternatively, the lack of collaboration among education stakeholders has been associated with poor quality learning outcomes and a narrow extent of service provision (Epstein, 2001; Friend & Cook, 2007).

Factors that support successful of collaboration practices between families and professionals

One of the most significant aspects of collaboration, which affects the success of collaboration in EI, is a proper understanding of the concept (collaboration). Here, education stakeholders need to understand that collaboration is not focused on being liked or liking other people; instead, the concept is about mutual trust and respect among the parties involved (Paulsen, 2008).

When different parties respect these values, collaboration flourishes. Therefore, some researchers have struggled to clarify that collaboration is not a stand-alone process, but rather a tool that education professionals and family members could use to improve the learning outcomes of children with special needs (Epstein, 2001; Friend & Cook, 2007).

The nature of special education also influences the success of collaboration in EI (Barron, Taylor, Nettleton, & Amin, 2017). For instance, the structures of special education funding could influence the quality of collaboration in many special education settings (Barron et al., 2017). Funding requirements may prompt education professionals to develop additional documentation that could influence their attitudes towards collaboration. For example, the increased use of Medicaid funds to finance special education activities in the US has increased the documentation requirements associated with providing education services to children with special needs (Hernandez, 2013).

Indeed, according to Hernandez (2013), it is possible to find one teacher developing at least three documents relating to one child. Such requirements have an effect on the productivity levels of education professionals, thereby influencing their ability to collaborate effectively with family members. Notably, the structure and funding requirements of special education services gives these professionals less time to collaborate with family members in the advancement of their children’s educational outcomes. Therefore, it is unlikely that collaboration would be successful in such a context.

Factors hindering successful collaboration practices between families and professionals

Although progress has been made to break down the barriers that prevent children with special needs from accessing quality education, several factors still prevent education professionals from effectively collaborating with other stakeholders to improve the quality of education for children with special needs. For example, the lack of a proper and clear definition of collaboration and a poor understanding of the framework that family members and education professionals should use to collaborate is a hindrance to the creation of synergy between both parties (Hernandez, 2013).

The lack of proper definition of the collaboration concept stems from concerns about the role of collaboration in affecting educational outcomes. Blue-Banning et al. (2004) add that the poor understanding of interpersonal relationships contributes to the failure of collaborative relationships.

Notably, researchers, such as Lynne Cook and Marlee Pugach (as cited in Hernandez, 2013) seek to assure stakeholders that collaboration is good for children, after highlighting evidence from improved learning outcomes and skill acquisition. This view was aimed at addressing concerns among stakeholders regarding the intent of collaboration. Nonetheless, the ambiguity associated with collaboration has also been linked with the inability to effectively implement the concept in EI because some people have confused it with coordination, which is a managerial task (Paulsen, 2008). Comparatively, collaboration (in the context of this study) refers to the willingness of different parties to take part in the education developed of children with special needs, regardless of the outcomes.

Hernandez (2013) adds to this discussion by saying that collaboration is easy to achieve, unlike coordination, which is a tedious process that requires alignment of strategic plans in a business setting. Based on this view, some educational professionals have not successfully embraced collaboration because they do not understand what it is about (Paulsen, 2008). Their inability to comprehend the concept partly supports recommendations by some researchers who highlight the need for proper training of educational professionals in the implementation of collaborative practices (Hernandez, 2013).

Another challenge characterizing the implementation of collaborative practices in EI is the unwillingness of some education professionals to embrace the concept (Hamilton-Jones & Vail, 2014). This problem has been attributed to ambivalence and significant difficulties of employing the concept in early intervention (Hamilton-Jones & Vail, 2014). Some researchers have attributed the unwillingness of some education professionals to collaborate with one another to the individualistic culture that characterizes many western countries (Hernandez, 2013; Goddard & Goddard, 2007; Whitbread et al., 2007).

Consequently, there have been attempts to relate the concept to a needs-based philosophy where it is used as a tool for creating and sustaining relationships among educational stakeholders (Hernandez, 2013). There have also been questions regarding why all fields of service provision in education have to be forced to collaborate with family members (Hernandez, 2013). For example, the field of language pathology in special education has registered the highest opposition to collaboration because professionals are not trained to collaborate with other people (Hernandez, 2013). This problem is also linked to other aspects of the education sector, which deem collaboration as contrary to their professional demeanor.

Therefore, they experience a strong preference to work independently (Hernandez, 2013). Three types of professionals manifest this attitude. They include teachers, occupational therapists and speech language pathologists (Hernandez, 2013).

In cases where individualistic barriers to collaboration are broken down and education professionals are willing to collaborate, there is often a lack of proper team structure to support collaborative efforts (Barron et al., 2017).

Here, it is also important to point out that, like other forms of relationships, collaboration may not flourish under certain conditions. Therefore, the adoption of collaborative practices is not an express admission that it will improve the learning outcomes of preschool children. One condition, which may influence the success of collaboration, is the privatization of the practice (Hernandez, 2013). In other words, collaboration among family members and education professionals may be affected by human dynamics.

A South Korean study authored by Bang (2018) shows that negative attitudes among teachers and parents towards collaboration was also another significant barrier to collaboration. The study also pointed out that some family members had unreasonable expectations regarding their child’s education, thereby causing them to be unreceptive to collaboration (Bang, 2018). Lastly, some researchers point out the negative effects that mandated testing of children with special needs has on collaboration with professionals in early childhood special education (Hopkins, Lorains, Issaka, & Podbury, 2017).

These tests create a high-stakes competitive environment in the special education setting, which nurtures an environment of uncertainty, which has a negative impact on collaborative practices (Hopkins et al., 2017). Therefore, education professionals spend a lot of time preparing children to meet mandated testing requirements as opposed to providing stimulating student instructions.

Summary

The empirical findings reviewed in this chapter, which have investigated collaboration between family members and professionals in early childhood special education are based in the United States. Therefore, we do not know the experiences and perceptions of parents in non-western countries, such as Saudi Arabia, regarding collaboration in early childhood education. Indeed, the literature is almost silent on how parents or families in non-western countries perceive collaboration in the inclusive learning environment or how their cultures influence the quality of partnerships among education stakeholders in EI.

In addition, no study has explored the perception of family members towards collaboration for children with special needs who are between 0 to six years old in Saudi Arabia. Consequently, there is a clear gap in the literature, which is centered on understanding how parents in Saudi Arabia view collaboration with education professionals. The proposed study will address this gap and provide a balanced and holistic view of collaboration in EI. To fill this gap, the proposed study will also focus on investigating families’ perceptions of collaboration in early childhood development in Saudi Arabia.

Methodology

Introduction and Research Gap

Given the increased attention early education experts have given to collaboration in the inclusive learning environment, it is important to investigate this matter from the Saudi Arabian perspective. As noted in chapter 2, a research gap exists due to the failure of past research studies to investigate the non-western parents’ perspective of collaboration with professionals in EI. In fact, no single research study based in Saudi Arabia has investigated families’ perceptions of collaboration in early childhood. To fill this gap, the current study proposes to investigate families’ perceptions of collaboration in early childhood development in Saudi Arabia. The proposed research methodology will be discussed below.

Research Method

The mixed methods approach will be used for the proposed study. The mixed methods design is defined as, “Research in which the investigator collects and analyzes data, integrates the findings, and draws inferences using both qualitative and quantitative approaches or methods in a single study or a program of inquiry” (Tashakkori& Creswell, 2007, p. 4). This technique involves multiple forms of data collection. Stated differently, it allows for the collection of both qualitative and quantitative data (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2007). Mixed methods research is considered a “third major research paradigm” (Johnson & Onwuegbuzie, 2004, p. 23), or the “third methodological movement” (Teddlie & Tashakkori, 2011, p. 285).

This approach will be employed in the proposed study because the researcher intends to use multiple data collection methods (quantitative and qualitative) to answer the research questions optimally and to “investigate a phenomenon of interest” (Teddlie& Tashakkori, 2011, p. 286). Additionally, the mixed methods technique aligns with the nature of the research topic because “collaboration” cannot be contextualized as solely a qualitative or quantitative issue.

Therefore, the mixed methods approach allows for the comprehensive analysis of the research topic (Watkins & Gioia, 2015). Moreover, the research questions that will guide the study investigation require a broad understanding of collaboration and a deeper interpretation of family views on the same. The mixed methods research approach allows for this kind of in-depth investigation and for a wide breadth of data analysis (Bergman, 2008; Creswell, 2003). To recap, the mixed methods approach will help to answer the following research questions.

Research Questions

Quantitative questions

- What are the trends of Saudi Arabian parents’ current perceptions of collaboration with professionals in early intervention?

- What are the potential barriers to Saudi Arabian parents collaborating in the delivery of early intervention services?

- Are there significant differences in Saudi Arabian parents’ perceptions of collaboration across demographic variables (e.g., gender, family income, severity of child’s disability, and family’s level of educational achievement)?

Qualitative questions

- What are the perceptions of Saudi Arabian parents regarding collaboration with professionals? What are the effects of cultural influences on Saudi parents’ collaboration with professionals? What communication methods are most effective for use in early intervention services in Saudi Arabia?

- What factors promote parents’ collaboration with professionals in early intervention services in Saudi Arabia?

- What factors hinder parents’ collaboration with professionals in early intervention services in Saudi Arabia?

Research hypotheses

- H1. Families have a favorable view towards collaboration in early childhood development in Saudi Arabia.

- H2. Cultural barriers are the greatest deterrents to the development of positive attitudes towards collaboration in early childhood development in Saudi Arabia.

- H3. There are significant differences in the level of support for collaboration in early childhood development in Saudi Arabia, relative to demographic differences.

Research Design

Multi-strand design is considered more complex than mono-strand design because it analyzes at least two types of research issues (Teddlie & Tashakkori, 2006). In this framework, the integration of qualitative and quantitative research designs could occur at different phases of the study. In detail, the sequential mixed technique has been selected for use in the proposed study. This technique often integrates two chronologically occurring strands of data (Teddlie & Tashakkori, 2006).

Their occurrence could happen in the form of qualitative-to-quantitative or quantitative-to-qualitative reviews (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2011; Teddlie & Tashakkori, 2009). The latter method will be used in the proposed study because the researcher intends to emphasize on the collection quantitative data, as opposed to qualitative information.

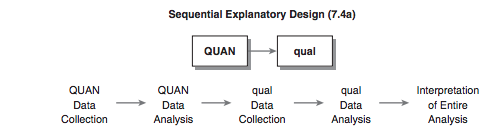

Therefore, the proposed study will rely on the sequential explanatory design. It encourages researchers to collect quantitative data, as the first line of information, and later the qualitative data, which is collected in the second phase (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2011; Creswell et al., 2003). The generation of quantitative data will later be used to undertake a qualitative interview that will expand the extent of the information analyzed.

Therefore, the main motivation for employing sequential explanatory mixed methods design is to use qualitative data to explain quantitative findings. The main objective of using sequential explanatory design is to use analyzed qualitative data to explain and provide an interpretation of the results of the quantitative data that will be collected first. In this design type, mixing occurs across chronological phases (Creswell et al., 2003).

The sequential explanatory design has several advantages, one of which is its effectiveness in creating a “feeling for the whole” because it involves the completion of successive passes of data collection in a non-linear manner (Teddlie & Tashakkori, 2009). This way, it will be possible for the researcher to develop subtle shades of meaning for the research questions after analyzing both sets of data (qualitative and quantitative). This technique also gives researchers an opportunity to review divergent information and switch perspectives in data analysis to get a broader understanding of the research issue (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2007).

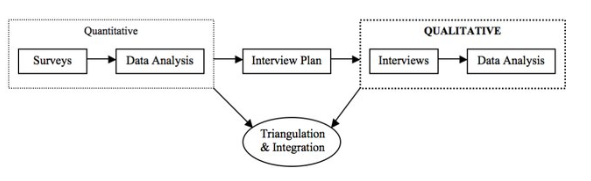

In addition, the qualitative data collection that follows can be used to examine unexpected quantitative data in more detail and with more explanation (Creswell et al., 2003). The main advantage of using this design is that the quantitative results will be deliberately prioritized. In other words, the quantitative phase of the study will be used to identify the characters of the participants to answer the research questions. Afterwards, the researcher will use the quantitative data to guide the purposeful sampling of participants for the qualitative phase (Creswell et al., 2003). Figure 1 below describes how this technique will be applied in the proposed study.

Comparatively, figure 2 below outlines the sequential explanatory design, which has more detail under an expanded typology for the mixed methods technique.

Data Collection Method

According to Creswell and Plano Clark (2011), the data collection process involves five steps as listed:

- selecting the participants;

- completing consent forms or getting permissions;

- gathering data;

- reporting the data;

- managing the process.

As mentioned in this document, the researcher intends to collect data using a mixed methods approach. The sequential explanatory mixed methods design, which allows for the collection of quantitative data in the first phase followed by the collection of qualitative data in the second phase, will provide the research design. Quantitative data will be collected as discussed below.

Quantitative data

Quantitative data will be collected in the first phase using questionnaires that will be distributed as surveys to the respondents as the main data collection instrument. The questionnaire examines parental participation and the barriers to early intervention services for deaf and hard of hearing children in Kuwait (AlRashidi, 2018) (see Appendix A). This survey technique is selected for use in the proposed study because it has a high efficacy in gathering responses from a large participant pool (Bickman & Rog, 2009).

The researcher will use an internet survey to get responses from the Web (Bickman & Rog, 2009). Participants will be asked to respond to a series of questions using a 5-point Likert scale. This type of scale is defined by Bernard (2011) as an ordinal psychometric tool for assessing people’s attitudes towards specific research issues. Therefore, respondents will have either to agree or disagree to a set of statements, using multiple-choice format, where they choose between “strongly agree,” “agree,” “are neutral,” disagree,” or “strongly disagree,” with the research statements.

The 5-point Likert scale is a useful tool for gathering respondents’ views because it standardizes them, thereby making it easier to analyze the data (Bernard, 2011). Additionally, the standardization of views into five key criteria is helpful to the researcher because statistical software will be used for purposes of data analysis. The 5-point Likert scale will support the integration of respondents’ views into the statistical software by categorizing them into quantifiable assessment units. In other words, the scale allows for the statistical integration of respondents’ views into the data analysis software. The scale is also a proven technique of data collection in the social sciences and has a reputation for being a universally accepted technique of survey data collection (Pallant, 2016).

Qualitative data

Qualitative information will be collected in the second phase of the research using interviews as the data collection technique. This process will only involve a selection of the participants who took part in the first phase of the investigation to explain the findings of the first stage of the investigation. The aim of these interviews is to investigate Saudi parents’ perceptions toward collaboration with professionals during the provision of early intervention services.

The interviews will be conducted via telephone or online communication platforms, such as Google Hangouts and Facetime (the time limit for the interviews will be approximately between 20-30 minutes). The qualitative method for this data collection phase will be semi-structured interviews to allow the researcher to give the interview subjects the opportunity to deviate from the specific question based on the flow of the conversation with the respondents.

However, these discourses will be limited to a selected number of themes that the researcher will seek to investigate in the second phase of data collection. Therefore, the interview questions that will be posed to the respondents will be identified before the interview begins and will be approved by the university’s academic advisory committee. Since the sample population will be comprised of Saudis only, the interview will be conducted in Arabic and will be recorded on an iPad or iPhone for purposes of data analysis. There will also be backup copies of the interview made using the researcher’s recorded notes, in either physical or electronic form.

This interview technique is selected for the current study because it allows the researcher to gather information in greater depth than quantitative data collection techniques allow (Tracy, 2012). It will also help the researcher to understand the major themes regarding collaboration in the inclusive learning environment that will emerge from the study, thereby adding a human dimension to the statistical data that will be generated in the first phase of data collection (Tracy, 2012).

Sample Population

Tailor (2005) defined a sample as a subgroup of a population. For the first phase of the investigation (quantitative analysis), research participants will be recruited from families that have children with disabilities who are under six years of age. They will be supplied with the questionnaire that will be uploaded to WSU Qualtrics (web-based questionnaire-type survey) as a survey. Links to the survey will be shared with selected early childhood education centers in Saudi Arabia.

The same link will be shared to several accounts that focus on early childhood education via Twitter® and Facebook®. Parents will be given first priority to participate as informants in the research. There will be no gender bias when recruiting subjects and either fathers or mothers may act as informants. If a parent is unavailable, a guardian will take their place. The parents (or guardians) must have children with disabilities who are enrolled in a Saudi early education center.

The second phase of data collection will be centered on the qualitative investigation. Here, the researcher intends to interview six to eight participants. This number is considered appropriate for qualitative studies, as noted by Teddlie and Tashakkori (2009) who said that the ideal number of participants is between six and ten. Consent will be obtained from the respondents before they take part in the second phase of the investigation and their contact information will be recorded after they have signed the informed consent form.

This process will ensure that their participation in the study is voluntary. The respondents could also withdraw from the research without any repercussions. Lastly, the information offered by the respondents will be confidential because their identities will not be disclosed or shared. If necessary, pseudonyms will be assigned to each participant to protect the respondents’ privacy.

Participants and sampling method

The researcher will recruit participants by contacting administrators of early intervention centers in major cities of Saudi Arabia, such as Jeddah and Makkah. The sample size was determined by using G*Power statistical software, which aligns with several computational techniques, such as ANOVA (UCLA Statistical Consulting Group, 2018) and the required number of the participants is (n=210) to reach significant result for two groups of respondents.

Participants will be recruited from the above-mentioned cities, as these urban centers are known for having essential early intervention services, such as language skills and occupational therapy services. These cities are also selectively chosen to be sampling centers because they are diverse and geographically dispersed. Therefore, one assumption of the study is that the families that will be contacted in these cities will largely represent the diversity of Saudi Arabia.

Convenience sampling will be used to recruit participants for both the qualitative and quantitative phases of data collection in this study. According to Etikan, Musa, and Alkassim, (2016), convenience sampling is defined as: