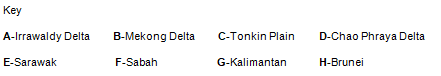

Map comparisons

Chinese immigrants form the largest minority group in the Southeast Asia. Noteworthy, their arrival can be traced back to the eras between Ming and Qing dynasties. Nevertheless, the largest influx falls between the years 1870 and 1940, the last phase of colonial rule, evident by over 20 million immigrants thronging the region.

Basically, they were motivated by the fact that, the European powers incorporated them into their system as administrators in their new colonies, and they too acted as trade partners. Eventually, they penetrated big cities, formed ‘Chinese town,’ and hence they were commercial kingpins.

This did not auger well with the Europeans powers, who noticed the burgeoning Chinese population cum influence and hence; they were forced to restrain them but with the Second World War on the horizon they were unsuccessful. Hitherto, Southeast Asia is a home to majority Chinese immigrants (over 30 million).

On many occasions they have been victimized by their hosts (Indonesian Muslims) with regard to their religious allegiance (Christianity), and their commercial superiority. However, the economic miracle that is enjoyed in the Pacific realm is owed to them.

The colonial power (French) that ruled a quadrant of this part of the sphere had christened it Indochina. As such, this is a manifestation of Chinese influence in this realm.

Buoyed by opportunities for settlement presented to them by European powers following the upheavals present in their motherland, many Chinese (seafarers, traders, fishermen among others) felt home and safe in this realm. As such, overtime, Chinese population and influence in social-political issues increased to date (Kimble 510).

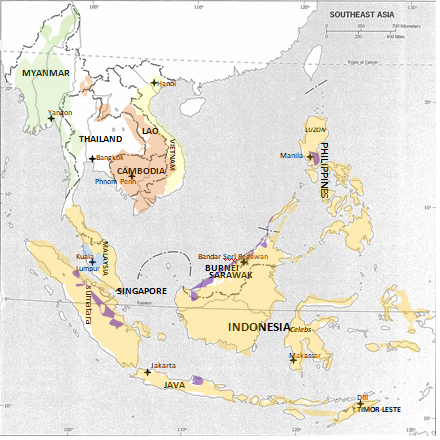

The degree of ethnic mosaic present in the Southeast Asian map typically portrays how diversified a culture is the realm. Basically, this region is a composite of cultures including Indo-Aryan (Hindustan), Miao Yao, Monkhmer, Chinese, Tibeto-Burman, Indonesian, Thai, Vietnamese, and Papuan among others. To further complicate this realm there exist cultural minorities that don mainly the Indonesia.

These include Javanese, Sundanese, Madurese, and Balinese among others. In a synopsis, the discrete groups that constitute this realm belong to unique religious affiliations. In essence, while the western part of the realm (Myanmar) is synonymous with Buddhism, majority of Indonesians are Muslims. On the other hand, majority of the Chinese speaking people that constitute the ethnic minorities of this realm are Christians.

These observations differ from the information provided for in figure 7-2 which gives a blanket religious pattern. However, the largest religious affiliation displayed by the most populous culture (Indonesians) is Islam. Buddhism has had quite an influence though biased in some regions like the Singapore in small pockets.

A state’s boundary forms the most sensitive part of a nation and thus; can spark wars between disputing parties. With respect to Southeast Asian map, many a positive feedback can be said about the post-colonial boundary. While a majority of the post-colonial maps (most notably in Africa) have unclear delineation, Southeast Asian maps are clearly defined and demarcated.

When drawing the map, unlike other maps, several factors were considered e.g. population densities. However, even with these many a diplomatic relations have been strained. For instance, the boundary between Papua and Papua New Guinea is a precarious situation. Significantly, boundaries are classified according to the “cultural landscape they traverse” (Schaefer 230).

The scope of this question requires that antecedent boundaries (boundaries that traverse inhabited tropical rainforest) be listed from several maps of the world. Examples are boundaries between: Malaysia and Indonesia, Nigeria and Mali, Cameroon and Nigeria, and many more others (MacLeod and Jones 677).

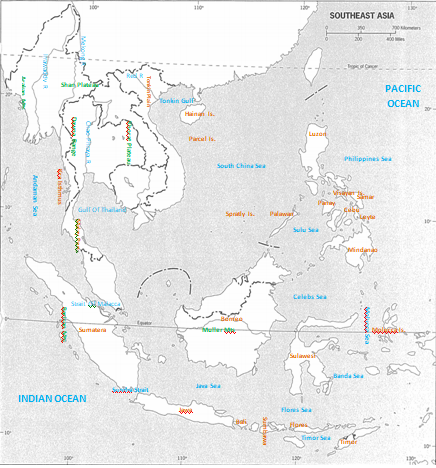

Map 1: Physical geography of Southwest Asia.

Map 2: Political cultural information.

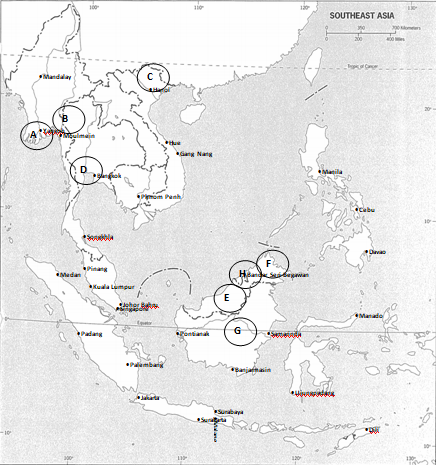

Map 3: Economic Urban Information.

Works Cited

Kimble, Hebert. “The Inadequacy of the Regional Concept” London Essays in Geography 2.17 (1951): 492-411. Print.

MacLeod, George, and Jones Mother. “Renewing The Geography of Regions.” Environment and Planning 16.9 (2001): 669-800. Print.

Schaefer, Frankline. “Exceptionalism in Geography: A Methodological Examination.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 43.3 (1953): 226-245. Print.