Demographics

Nowadays, Dubai is commonly referred to as the most rapidly developing city in the Gulf region. The principal reason for this is that for the duration of the last few decades the Emirati capital has been enjoying the reputation of one of the world’s well-established tourist and business destinations. In its turn, this explains the qualitative aspects of the demographic situation in Dubai. The most notable of them are as follows:

As of 2015, the city’s population amounted to 2,446,675, with the number of permanent (Emirati) and non-permanent (expatriates/temporary workers) residents having been estimated to account for 222,875 and 2,223,800 respectively (“البابالأول-السكان” 2).

The main implication of this statistical insight is that Dubai is extremely diverse, in the cultural sense of this word. The population’s male/female ratio is shifted rather dramatically towards the representatives of “stronger sex”. In the same year, the number of the city’s male residents accounted for 1,703,355 and the number of female residents for 743,320 (“الباب الأول- السكان” 1). In its turn, this can be interpreted as the indication of the Dubaian society being strongly patriarchal – something that correlates well with the Emirati government’s commitment to the protection of Islamic traditional values.

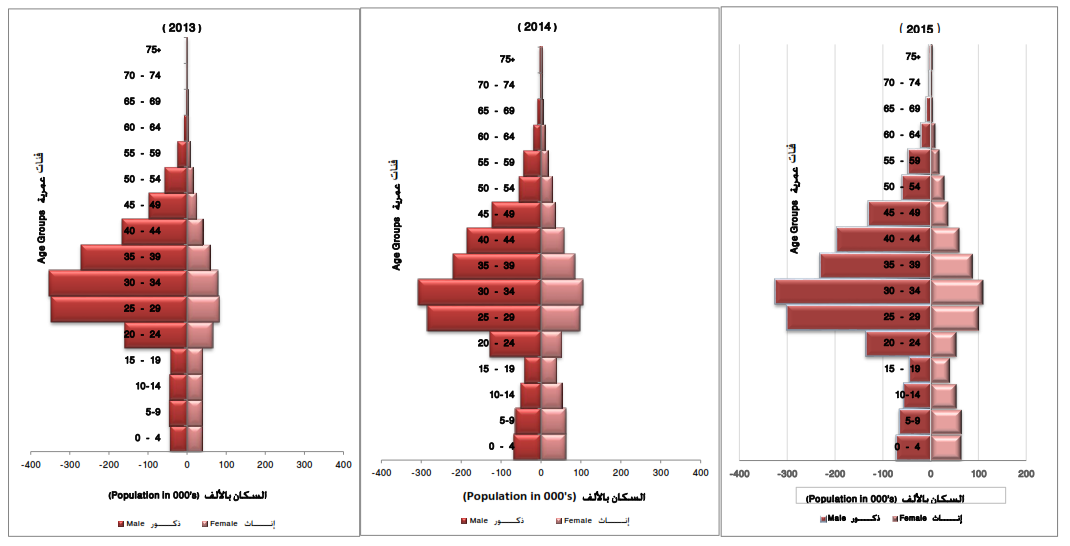

As it appears from Population Pyramid by Sex (“الباب الأول- السكان” 5), through the years 2013-2015, the largest portion of Dubai’s population continued to consist of middle-aged males (see Fig. 1), which is consistent with the earlier mentioned fact that Dubai provides many employment opportunities for foreign workers.

Nevertheless, even though the percentage of the city’s senior residents appears insignificant, there is a good reason to believe that it will continue to grow as time goes on. The validity of this statement can be illustrated by the steady increase in the number of suburban households that surround Greater Dubai. Whereas in 2013 there were 357,773 of them, by the year 2015 the concerned number went up to 413,310 (“الباب الأول- السكان” 6). Our suggestion is validated even further, concerning the fact that life expectancy among Dubai’s residents is estimated to be as high as 82 years (“الباب الأول- السكان” 19).

What this means is that there is indeed much rationale for the government of Dubai to invest in ensuring the city’s infrastructural integrity, especially given the upcoming Expo 2020 event. As of today, there remains much uncertainty about the number of disabled people living in Dubai, as well as what these individuals consider the foremost challenges within the context of how they go about trying to achieve social self-actualization.

Nevertheless, there is a good reason to believe that the situation, in this regard, will change for better by the end of this year. As Miran pointed out: “Dubai will have a database for people with disabilities by 2017 to help develop policies and services that best integrate them into society”. Such a would-be development is indeed thoroughly justified because the current socio-economic realities in Dubai establish many objective preconditions for the disability rate among residents to be on the rise – contrary to the fact that the UAE features some of the world’s highest standards of living. This explains our choice for the subject of this research – specifically, the population of physically disabled individuals in Dubai.

Social Needs in Dubai and its Shortcomings

The main problem, faced by the chosen category of Dubai’s socially dependent residents, is that they often experience difficulties while trying to get around – both within the city and outside of its municipal boundaries. Probably the most troubling of these difficulties is that the “special needs” people (with the majority of them being wheelchair-bound) find it utterly challenging getting off the walkway into the main road and vice versa, as there are simply not enough curb ramps alongside pavements in Dubai.

Because of it, concerned persons’ traveling choices become severely limited. As Bindiya Farswan (“a 31-year-old Dubai resident from India, who is wheelchair-bound due to cerebral palsy quadriplegia”) noted: “I use the roads when I have to get somewhere, not the walkways” (Geranpayeh 1). It is understood, of course, that the described situation is hardly tolerable, especially given the fact that the “expulsion” of disabled residents onto the city’s streets contributes even further towards making the problem of traffic jams in Dubai ever more serious.

Up until this date, there have been a few strategies deployed under the auspices of the Road and Transport Authority/RTA to make it easier for the physically disadvantaged residents to commute through the city. In this regard, we can mention the following:

- New buses in Dubai are now equipped with the floor-lowering system, so that wheelchairlers do not experience any problems getting inside (Geranpayeh 3).

- The city’s “water buses” now have a special space, reserved exclusively for people in wheelchairs. Each of such “buses” is presupposed to provide accommodation to no less than 3 disabled commuters (Geranpayeh 3).

- Physically disadvantaged drivers are entitled to several different parking privileges while being exempted from the requirement to pay any parking fees, applicable to Dubai’s able-bodied drivers (“People of Determination”).

- Taxi Dubai operates the fleet of seven taxis, specifically reserved for the clients with “special needs”. According to Geranpayeh, these taxis are: “fitted with special lifts for wheelchairs, artificial respiratory systems, wheelchair on board and seats for companions” (4).

- RTA came up with the provision for the design of the would-be built Dubai Metro to be observant of the specifics of the disabled individuals’ commuting needs (Geranpayeh 4).

Generally speaking, the deployment of the earlier outlined strategies proved to be rather effective, in the sense of empowering the Dubai’s disabled residents within the context of how they address different transportation-related challenges: “Dubai has made it quite easy for individuals with special needs to remain mobile and access public places” (Geranpayeh 1). Nevertheless, the undertaken measures, in this respect, are far from being considered exhaustive. Moreover, there is an objective reason for what has been done so far to accommodate the needs of physically disadvantaged Dubaians to prove only partially workable.

For example, as opposed to what it is the case in most Western cities, Dubai’s traffic lights at the pedestrian crossings do not give out an audible signal – much to the blind residents’ dismay (“Irish Traffic Lights”). Yet, it is namely the fact that the implementation of these measures does not quite adhere to the principle of systemic wholesomeness, which appears to represent their main shortcoming. The reason for this is that, as it can be inferred from what has been said earlier, the currently enacted strategies on the way of making Dubai “special needs”-friendly presuppose that ensuring the disabled people’s well-being has the value of a “thing in itself”. Such an assumption, however, is flawed to an extent, because it de facto stands opposed to the idea that the agenda of the city’s physically handicapped residents are inseparably interconnected with the agenda of the Dubaian society as a whole.

The thematically relevant social enterprise that I am going to propose aims to eliminate the discursive inconsistency in question. The theoretical premise out of which my initiative derives can be formulated as follows – instead of being solely concerned with helping physically handicapped Dubaians to get around the city,

the enactment of the “special needs”-friendly policies in Dubai should also aim to benefit the city’s able-bodied residents. The viability of this suggestion is reflective of both the fact that Dubai’s disabled residents are naturally driven to favor buses as the primary mean of traveling and the fact that the government is currently trying to find the best way to address the problem of traffic jams on the city’s roads. One thing is clear about the latter objective – it can only be achieved by providing as many Dubaians as possible with the strong enough incentive to refrain from using their vehicles to commute. As Tesorero argued: “The main solution (to Dubai’s congestion with traffic)… is to get more vehicles off Dubai roads. Even if the city road network is expanded, it will not be enough to keep pace with the increasing population and demand for cars”. The available statistical data provides us with insight into why the majority of residents continue to prefer driving cars, as opposed to riding buses.

As of today, there are 1,122 operating buses in Dubai (“Dubai in Figures 2017”). If we divide 2,446,675 (Dubai’s population) by this number, the derived population/bus ratio will equal 2180 – something suggestive of the scarcity of buses in Dubai (in large Western cities, there is approximately 1 bus per 1000 residents) (“Number of Buses”). In Dubai, the average waiting period between the arriving and departing busses is estimated to account for 30 minutes (“How to Get from Dubai”).

This again suggests that the number of buses in the Dubai’s system of public transportation is hardly adequate – the actual reason why the city’s streets continue to be clogged with more and more privately owned cars, even though most Dubaians are fully aware of the sheer abnormality of such a situation. If they were to choose between the options of having to spend 20-30 minutes riding a bus or to waste 1-2 hours being stuck in traffic while trying to get to the same destination in a car, most of them would favor the first option. The first option, however, can only become available to Dubaians if the mentioned waiting intervals between buses are no longer than 5-10 minutes.

The discursive implication of the above-stated is quite apparent – RTA will need to acquire 2,224 more buses (equipped with wheelchair lifts for the disabled). By doing it, the concerned organization will be able to “kill two rabbits with one shot” – to increase the commuting empowerment of disabled residents and effectively solve the problem of traffic jams in Dubai. Given the average cost of purchasing one new bus (about $100,000), the suggested social enterprise’s overall cost will amount to approximately $220 million. It is understood, of course, that as compared to building new highways/widening the old ones (something that usually requires the budget of billions of dollars and consequently spawns corruption), my initiative would prove a much more cost-effective/workable way of increasing the residential appeal of Dubai.

Conclusion

I believe that if implemented practically, the proposed social enterprise will prove utterly successful – all due to its strongly defined systemic quality. As it was shown earlier, the Dubai government’s current approach to helping disabled Dubaians to cope with the transportation-related challenges is indeed objectively predetermined. However, it does not take into consideration the fact that, within the context of how one goes about trying to ensure the effectiveness of infrastructural initiatives in urban areas, the application of linear logic often backfires. We can only welcome what has been done so far to empower the city’s physically disadvantaged residents, but the fact remains – most of them are strongly accustomed to using either their cars or the RTA-operated buses for getting from point A to point B.

In its turn, this implies that for as long as Dubai’s roads continue to remain congested with traffic, these people will not be able to benefit a whole lot from the ongoing expansion of the city’s “special needs” infrastructure. This once again illustrates the full soundness of the proposed social enterprise, on my part. The enterprise’s only drawback is that, despite being systemically sound and cost-effective, it can hardly be deemed “sophisticated” enough to represent much appeal to the governmental officials, in charge of integrating the concept of CSR in the very philosophy of the city’s infrastructural functioning. Therefore, it is rather unlikely that it will ever be considered seriously. This, however, does not make the related suggestions, on my part, any less viable.

Works Cited

“الباب الأول- السكان.” Government of Dubai, 2015. Web.

“Dubai in Figures 2017.” Government of Dubai, 2017. Web.

Geranpayeh, Sarvy. “How Disabled-Friendly is Dubai?” Gulf News. 2016. ProQuest. Web.

“How to Get from Dubai to Abu Dhabi Without a Car.” What’s On, 2017. Web.

“Irish Traffic Lights.” YouTube. Web.

Miran, Aisha. “Dubai to Have Database of People with Disabilities by 2017.” Gulf News, 2015. Web.

“Number of Buses per 1,000 People.” Urban Bus Toolkit, 2016. Web.

“People of Determination.” Government of Dubai, 2017. Web.

Tesorero, Angel. “Traffic Jams in Dubai Cost Time, Money and Health.” Khaleej Times, 2016. Web.