Introduction

Northern Canada, which is also referred to as the North, is the extensive northernmost region of Canada, which is distinct from other parts of the world by its topography and administrative structure. When the term northern Canada is used within a political context, it refers to three northern territories in Canada. These, according to Britton (123), are Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut.

From the year 1925, Canada has claimed large portions of the Arctic, claiming that they lie within her border. This is especially the region lying between 60 degrees west and 141 degrees west longitude (Doem & Kinder 53). This portion extends all the way to the north of the North Pole.

It includes all the islands in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago and Herschel (Doem & Kinder 54). The country also claims the territorial waters that surround these islands.

The large part of Northern Canada is permanently covered by ice, making it unsuitable for agriculture. Construction is also impossible, and where it occurs, it is characterized by a lot of hazards both to the constructors and to the habitants.

This is given the fact that heat from the house may melt the snow above which it lies, making it sink (Smith 12). Construction activities may also destabilize the packed snow, which may lead to avalanches.

However, despite this fact, the area is made up of geological regions of varying types, some of which are habitable by man. One of them is the Innuitian Mountains, part of the famous Arctic Cordillera mountain range (Muise & McIntosh 67). This area is especially different from the rest of the Arctic Region, which is mainly composed of lowlands.

The northern parts of Canada were relatively uninhabited for a very long time. This is despite the fact that, with an area of approximately 3,921,739 kilometre squares, the area makes up about 39.3 percent of Canada geographically (World Diamond Council 3). Northern Canada is bigger than India, which is only 3,287,263 kilometre square (Bastedo 43).

However, over the past two decades, the population density in this area has significantly increased. According to the latest census statistics in this country, which were conducted in 2006, the area is still sparsely populated despite this increase in population density.

Northern Canada is home to about 101,310 people as of 2006 (Doem & Kinder 50). This is as compared to about 31,511,587 in the other parts of the country (Doem & Kinder 50).

Analysts have attributed this population growth to the rise of the extraction industry in this region over the last few decades. This is especially the diamond mining industry, given the fact that this area has one of the world’s largest deposits of diamond.

The diamond production industry has brought several changes to the northern region of Canada. Opinion is divided between those who view the production as having impacted the area positively and those who view the impact as largely negative.

Positive effects include reduced levels of unemployment, development of infrastructure such as roads and communication networks among others. Negative impacts include destruction of the environment as well as destabilization of the ecological balance in the area.

This research paper is going to look at how the extraction industry has transformed both the natural and social environments in the Canadian north (Arctic). The researcher will especially look at the impact of diamond exploration on the economic and demographic structures of Northern Canada.

The major theme of this paper is that, despite the positive changes brought about by diamond and other mineral productions in Northern Canada, the wellbeing of the indigenous population in the region has not significantly improved.

Thesis Statement

The following is the thesis statement of this research paper:

Despite the positive changes that have been brought about by diamond and other mineral production in Northern Canada, the wellbeing of the indigenous population has not significantly improved.

Background Information

For many centuries, Northern Canada has been regarded as one of the largest uncivilized regions in the world (Smith 12). This is given the fact that its climatic condition could not support civilization for the longest time. The permafrost made it impossible to carry out farming and construction of residences, making it hard for humans to survive in this region.

Canada is the third largest exporter of diamond in the world. By the year 2003, this country accounted for about fifteen percent of the value of diamonds that were produced in the world in that year (Smith 2). The exploration for this mineral started in the mid 1990s.

Actual mining started in 2008, with several prospecting companies establishing mines in various parts of the regions (Gibson & Klinck 118). One of the first companies to establish mines in the northern part of Canada was Ekati Mines (Gibson & Klinck 118). This was soon followed by Diavik mine, and according to Smith (1) by the year 2006, the total number of mining companies in Northern Canada were expected to rise to four.

The contribution that these mines have made to the community in these parts of Canada is significant. For example, in 2002, production of this mineral made up about 19.9 percent of the total real output in this part of Canada (Smith 3). From this fact, it is obvious that despite it being a recent industry in the region, it did make a significant impact on the growth of the economy.

This fact was captured in a report that was drafted by the Centre for the Study of Living Standards (herein referred to as the CSLS) in 2002.

The report, titled Productivity Trends in Natural Resources Industries in Canada, was presented to the Natural Resources Canada (herein referred to as NRCan), and it analyzed several attributes of the economy as they related to the country’s natural resources within a period of forty years. The report found that mining is one of the major drivers of the country’s economy, and diamond production played a significant role in this.

The mining took place in areas that were devoid of trees and human habitation. But the production needed human labour, and this led to the rise of population in these areas. The infrastructure of the northern region has also improved since the start of mineral production.

This is given the fact that the mining activities called for a road network to transport both the products and labour needed. Communication was also needed, and as such, this infrastructure also developed.

However, the benefits of this production have not really trickled down to the aborigines in this region, and as such, their life has not significantly improved. One of the explanations for this situation is the fact that most of the mines are owned by outsiders, and the communities own only a small portion of the companies. As such, most benefits accrue to the foreigners.

The aborigines only benefit by providing peripheral services such as labour for the production. The contact with the foreigners have also negatively affected the aborigines’ population, especially given that the foreigners brought with them diseases to which the aborigines had no natural immunity to. As such, many aborigines died from diseases such as small pox.

Research Questions

The following are the research questions for this paper:

- What are the various impacts of diamond mining to the aboriginal community in Northern Canada?

- How can the positive impacts of this activity be sustained?

- How can the negative impacts of this activity be mitigated?

- Has the benefits of diamond production in this region trickled down to the aborigine community?

- What is the future for diamond mining in Northern Canada?

Research Objectives

The research objectives of this study are closely related to the research questions. The major objective is to analyze how the extraction industry has both natural and social environment in the Canadian north. The study will have several specific objectives, and it is the attainment of these that will lead to the effective attainment of the major objective. The following are the specific objectives for this research:

- To analyze the impacts of the extraction industry on the northern Canada communities

- To analyze how the negative impacts of mineral extraction industry can be mitigated and the positive impacts sustained

- Analyze the factors that make the aboriginal community benefit or lose from the extraction industry in Northern Canada

- Analyze the future for extraction industry in Northern Canada

Methodology and Structure of the Paper

After the introduction, the paper will start with an analysis of the population growth in Northern Canada. The researcher will review how the population has increased or decreased over the years, and this will later be connected to diamond mining in the region.

The demographic trends in this region will be analyzed, and an explanation sought for the continuous flow of people to this area over the years. This information will be obtained from several sources, such as Canada’s National Statistical Agency.

The economic development of this region will then be analyzed. Aspects such as income per capita, gross domestic product and such others will be addressed. The aim of this will be to determine the economic impact of diamond exploration.

The transformation that the mining activity has had on the landscape of the region is another issue that will be analyzed. To this end, a case study will be made of the city of Yellowknife. The development of infrastructure in this city will be analyzed, and the connection between this and the mining industry.

Significance of the Study

The findings of this study will be important to several stakeholders in this matter. The findings will reveal how the extraction industry transforms both the natural and social environments of a region. Environmentalists and miners will use this knowledge to come up with policies that will maximize the benefits of the activity while mitigating the negative impacts.

Agencies interested with the wellbeing of the aboriginal community will use this information to come up with strategies that can be used by these communities to benefit more from the extraction industry while avoiding the costs associated with the same.

Mining is an integral part of Canada in general and of the northern part in particular. This being the case, it becomes important to know how this activity has shaped this society and how it will affect the future of the country. The findings of this study will go a long way to address this.

Diamond Exploration In Northern Canada

Introduction

Before embarking on the issue of population and economic growth in this region, it is important to first address the issue of diamond exploration and how it has changed over the years. A brief overview of this exploration will provide a context for the analysis of the impacts that this activity has had on the region.

Diamond Exploration in Northern Canada: A Brief History

In mid February, 2011, the Ekati mines in Canada made a history of sorts in the world’s diamond market. A diamond from these mines, aptly named the Ekati Spirit, raised the spirits of diamond merchants in this country by fetching a staggering $6 million in an auction (Greig 2).

The piece of gem was the size of a cherry, and it weighed 78 carats (Greig 2). But it is the distinct clarity of the stone, coupled with its colour that made it break the history previously set at $1.2 million a couple of years in the past.

It is more likely that this diamond came from one of the Ekati mines in Northern Canada. This scenario depicts the niche that Canadian diamonds have curved for themselves in the world market, breaking records and setting new standards. But this development illustrates the current status of diamond extraction and marketing in Northern Canada. But how did we get where we are now?

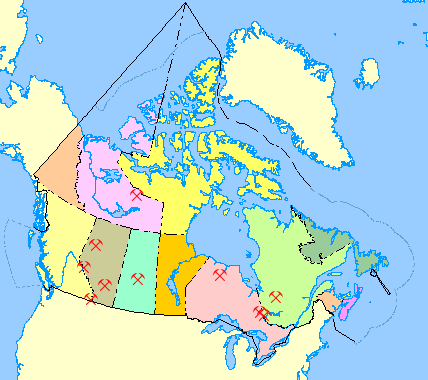

The map below represents the extent of diamond exploration as of 1997:

The history of diamond exploration in Northern Canada is an interesting one. In early 19th century, random findings of diamond were made in North America, and most were made on glacial drifts (Greig 4). Scholars hypothesized that the diamonds had been carried by glacier from the north. A study on ice flow was made, and it revealed that James Bay Lowlands, Northern Canada, was the probable source of the diamonds.

However, it was not until the beginning of the 1960 decade that systematic explorations were made on commercial basis in this region. DeBeers, a South African mining company, was one of the first companies to show interest in this region (Wilkes 9).

But the first discovery of diamond was made in September 1991, after decades of incessant explorations involving a lot of financial and human resource investment. It was made by Dia Met and BHP, a multinational company that was working on the Lac Gras region (Bastedo 40).

This discovery raised the exploration activity for diamonds to fever pitch levels. More mines were commissioned, and Canada became one of the world’s top producers of diamond, only third after Botswana and Russia.

Diamond Exploration in Northern Canada: A Study of Major Producers

Ekati Mines

Ekati is one of the first mines in this region, having been commissioned on October 14th, 1998 (Wilkes 13). It remains one of the largest producers of this commodity, located in the Lac de Gras region (Wilkes 13). By the year 2000, the production from this mine has risen to about four million carats per annum.

This is roughly 3 percent of the whole world’s production of diamond, making Ekati, and Canada in extension, to be one of the major players in the diamond market. It is expected that the mine will be economically viable for the next eleven years (Wilkes 14).

The mine is joint venture of BHP Diamonds Inc. and Dia Met Minerals Ltd, the former been an Australian corporation with operations in other parts of the world (Gibson & Klinck 129). The operations of this mine started earlier than the incorporation of the company, with one of the Canadian partners, a geologist by profession, carrying out studies in the Mackenzie Range, near the border between Yukon and Northwest Territory.

The mine lies on a barren land, part of the Northwest Territories, and despite the barrenness, the land holds an array of flora and fauna. Animal life includes caribou, grizzly bears, and ptarmigans among others. This is together with a robust marine life in the lakes that the mine covers, marine animals such as slimy scupins, swim-trout just to mention but a few.

The robust flora and fauna of the area has been affected by the mining operation. This is for example the draining of lakes and excavation of caribou’s migration routes. More on this issue will be provided later in this paper.

The Diavik Diamond Mine

This is another major player in the northern diamond production business. It is located in the North Slave Region, Northwestern Territories, just like the Ekati mines highlighted above. The mine was surveyed in 1992, but the erection of the mining facilities were to begin nine years later, in 2001 (Monro, Wicander & Hazlett 369).

Commercial production of diamonds from this mine began in early 2003, several years after the commencement of operations at the Ekati mines. It is expected that it will be economically viable for the next 20 years (Monro et al 369).

Just like Ekati mines, this is also a joint venture operation. It is co-owned by Harry Winston Diamond Corp. and Diavik Mines Inc., the latter been an operating arm of Rio Tinto Group (Monro et al 368).

Initially, the mine operated through open pit technique, wrecking damage to the topography of the region. However, from March 2010, authorities in this mine started to incorporate underground mining in their operations. By 2012, it is expected that the mine will be fully operating through underground mining (Monro et al 367). This transition was made as an effort to conserve the environment that supported the local community.

It is important to note at this juncture that the two mines above are not the sole operators in Northern Canada, though they are some of the major players in the industry. There are other mines owned by companies such as Snap Lake Diamond Mine, Arctic Star Diamond Corp., Ashton Mining Canada Inc. among others. The two case studies above were just selected for their central role in the industry.

Population Growth In Northern Canada

Introduction

It is a fact beyond doubt that Canada has experienced a significant population growth in the recent past. However, it is debatable how much of this growth can be attributed to the rise of the mining industry in the country.

It is evident that since the start of the mining industry, population has significantly increased, but it is not clear whether there are other factors that would have led to this development, apart from the increased mining activities.

Population Growth in Canada

The most recent census in this country was carried out in 2006. It is noted that the country recorded a higher population growth between the years 2001 and 2006 than the preceding inter-censal period (Doem & Kinder 50). This growth was the highest among all the G8 countries, of which Canada is a member.

There are those who are of the view that this growth can be attributed to the rise in mining activities in the country. However, this is challenged by the realization that almost 90 percent of this growth within the five years was largely concentrated in large urban centres (Prno, Bradshaw & Lapierre 5).

This is despite the fact that most of the mining activities take place in remote areas such as the northern regions, and as such, it becomes hard to attribute the population growth solely to the extraction industry. For example, Alberta and Ontario areas, which account for a small portion of diamond production in the country, accounted for two thirds of the population growth within the five years period.

But one can argue that the effects of diamond mining on the country’s population growth are not limited to the remote areas within which the mining takes place.

The money from the mining is invested in the large urban areas, improving the economy and the infrastructure, and in extension retaining a higher population and attracting more people to these cities. As such, the mining industry cannot be totally excluded from the population growth in Canada.

According to the 2006 census figures, the current population in Canada stands at 31,612,897 (Prno et al 3). This represents an additional 1.6 million people over the 2001 census statistics. As earlier indicated, Ontario was one of the cities recording high population growth, standing at 19.2 percent (Prno et al 8).

Several factors, apart from the increased mining activities, have influenced this growth in population. This includes the aboriginal population, extension of the country’s traditional boundaries together with migration to the country (Bastedo 42).

The latter is especially significant given the fact that Canada is one of the most open societies in the western world. However, the fact that a large portion of this country is inhabitable, especially in the north, reduces its carrying capacity.

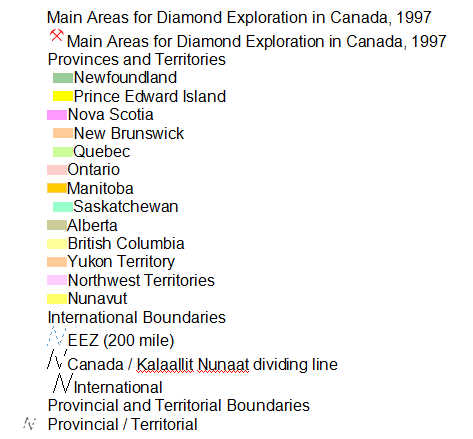

The figure below represents the growth of population since 1867 to 2002. Note that the population growth has been on an upward trend in this period:

Population Growth in Northern Canada

Having looked at the population growth in Canada as a whole, it is now to look at the trend in the northern areas, the area of interest for this paper.

As already indicated in this paper, despite the vastness of the region, it is still sparsely populated. The 2006 census statistics indicated that it is only about 101,310 people who live in this area (Prno 3). The scanty population of this area can be appreciated if one compares these figures with those of the whole country that were given above.

The population density in this area, going by the figures of the 2006 census, stands at 0.03 persons per square kilometre, a low concentration by any standards. For Yukon, the concentration is at 0.03 persons per square kilometre, and 0.01 per square kilometre in the case of Northwestern Territories (Prno et al 8).

Like the rest of Canada, northern Canada has also recorded population growth between 2001 and 2006. In Nunavut, the population grew from 26,745 in 2001 to 29,474 in 2006, a 10.2 percent increase (Prno et al 8).

In Northwest Territories, the population grew from 37,360 to 41,464 within the same period, an 11.0 percent increase. Yukon Territory recorded a similar growth, rising from 28,674 to 30,372, a 5.9 percent increase (Prno et al 8).

According to the figures released in 2006 census, 52.8 percent of the residents in this area were of aboriginals. Yukon had 25.1 percent, Northwest Territories 50.3 percent and Nunavut had the highest concentration of aborigines, standing at 85.0 percent of the total population (Prno et al 8).

From the above discourse, it is obvious that, given its concentration in this region, the indigenous community is the one that is greatly affected by the mining taking place in northern Canada. This being the case, it is important to take these communities into consideration when appraising the impacts of mining in the region.

Economic Growth In Canada

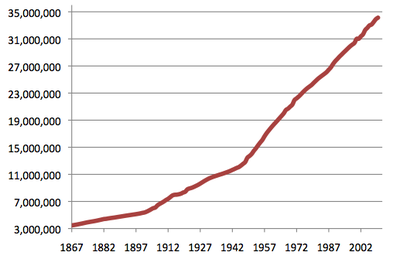

Canada is regarded as the world’s 10th largest economy, and most of this is credited to the country’s natural resources (Muise & McIntosh 70). In the last quarter of 2010, the Gross Domestic Product grew by about 0.80 percent as compared to the last quarter of 2009. On average, the GDP growth of this country on a quarterly basis is 0.84, and this has been sustained since 1963, with little variance (Muise & McIntosh 79).

The figure below represents the quarterly growth rate of this country’s GDP since 2007:

It is noted that the economy of this country is diversified and highly developed, and it is one of the few developed nations whose economies are net exporters (Britton 130). Foreign trade accounts for a larger part of this country’s economy, and the United States of America, the country’s southern neighbour, is her largest trade partner.

The mining industry has largely contributed to this economic growth. The fact that Canada is the world’s third largest exporter of diamond is proof to this, given that exports account for a substantially larger part of this country’s economy. As such, it is not farfetched to claim that diamond mining has impacted positively on this economy.

Economic Growth in Northern Canada

Analysts note that northern Canada experienced some of the fastest economic growths in the country and in the world in extension. For example, according to Doem & Kinder (54), three of the country’s five regions that recorded spectacular economic growth between 1999 and 2008 are located in the north. These are as indicated below:

Top Five Economic Growth Regions in Canada (1999-2008)

- Northern Newfoundland and Labrador – 63.8% (Prno et al 9).

- Southern Newfoundland and Labrador – 59.9% (Prno et al 9).

- Northwest Territories – 55.2% (Prno et al 8).

- Nunavut – 28.5% (Prno et al 8).

- New Brunswick – 21.4% (Prno et al 8).

Newfoundland and Labrador, Northwest Territories and Nunavut are all regions in Northern Canada. According to Gibson & Klinck (131), mining, oil and gas industries has accounted to this expansion in the economy.

This is more evident given the fact that diamond was discovered in this region in the early 1990s, and the economy has been growing positively ever since. This observation further proves that diamond mining is a central part of this region’s economy.

Ironically, northern Canada also hosts four of the five regions that recorded the slowest economic growth rates between 1999 and 2008 (Prno et al 9). These are as listed below:

Five Regions with Lowest Economic Growth Rates in Canada (1999-2008)

- Northern Quebec – 2.2%.

- Northern Ontario – 3.0%.

- Northern Alberta – 7.9%.

- Southern Ontario – 8.5%.

- Northern Manitoba – 12.2%.

The above table points to the fact that the benefits of diamond mining are not uniformly distributed in northern Canada. It appears that the benefits of the extraction industry are limited to the specific regions that it takes place. For example, northern Québec and northern Ontario relies heavily on forestry and not mining like Northwest Territories and other areas.

Benefits Of Diamond Mining In Northern Canada To The Indigenous Community

Introduction

This paper has alluded to the fact that diamond mining has had several benefits to communities living in this region. For more than a century, this activity has been a central pillar of this region’s economy. Benefits range from reduced unemployment levels, social benefits as well as economic development. In this section, some of these benefits will be highlighted.

Impact on Employment

Analysts are of the view that since diamond mines started operating in the northern region in the early 1990s, several employments related benefits have been realised. For example, between 1995 and 2008, this sector provided direct employment to more than 25,000 persons per year in the whole country (World Diamond Council 4).

Indigenous communities from northern Canada accounted for 13,000 persons per year as far as employment is concerned (Santarossa 8). These figures are cumulative, reflecting the total number of employees during this period.

In 2006, 975 aboriginal Canadians were directly employed in the mining of diamond industry (Prno et al 7). This was 25 percent of the total workforce in this industry this year. As earlier noted, majority of Canadian aboriginals reside in the north, and as such, it is in order to argue that they were the beneficiaries of this economic development.

Social Benefits

It is a fact beyond doubt that the diamond mining industry has improved the quality of life for the aboriginals in northern Canada. The benefits are viewed variously be different people in the society, and there are those who argue that the status of the aboriginals’ life is not significantly different now as compared to the period before the onset of the mining industry.

Gibson & Klinck (118) argue that more than twenty aboriginal and northern Canada communities have benefited from the mining industry, and their quality of life has largely improved.

This has led to a multitude of innovative and award winning educational initiatives by the companies. Some of these are outlined below (Gibson & Klinck 23):

Scholarships Targeting Post Secondary Education

Many families from the aboriginal community have been able to send their children to higher learning institutions courtesy of the mining industry. By paying for their post secondary education, the mining industry uplifts quality of life for the children, their family and the whole community in extension.

Aboriginal Leadership Development

The companies mentor the community leaders through workshops and such other forums. This ensures that the leaders can competently lead their community, and are better placed to fight for their rights. This has greatly improved the quality of life for the whole community.

Apprenticeship Trades Training

Mining companies especially train their workers, equipping them with skills on mining and other economic activities in the industry. Most of these workers are drawn from the aboriginal communities and their improved skills leads to their improved marketability, meaning that their labour is worth more in the market.

Aboriginal Employment Partnerships

These partnerships ensure that a considerable segment of the mining companies’ labour force is composed of aborigines. This increases the per capita income of these residents, making them afford basic items in the market. This, at the end of the day, improves their quality of life significantly.

Workplace and Community Based Skills Training Programs (Monro et al 360)

The companies, through workshops and similar forums, trains and equips the members of the community with skills that are needed in the social and economic contexts of their life. For example, they are trained on skills such as operation of mining machinery, or on conflict resolution and fighting addiction. This ensures that the community experiences an all round benefit from these companies.

The impact of the above initiatives to the quality of life in the community can be deciphered from an analysis of various attributes in the community. For example, between 1994 and 2007, the rate of high school graduation in Northwest Territories, one of the areas that host a large number of aborigines, rose by 20 percent (Prno 9).

In 1994, the graduation rate was 36 percent, and this rose to 56 percent by the end of 2007 (Prno 9). This is one of the success stories that can be cited as far as the intervention of the diamond mining industry in this region is concerned.

There are other community development initiatives that are undertaken by the diamond mining industry in northern Canada. For example, the mines ensure that the transportation routes in these areas are upgraded. This is significant, noting that before the entry of these companies, some of the communities in the north were cut off from the rest of the country.

The mines invest on roads, airports and other transport infrastructure. For example, the Diavik mines constructed an ice road that connected the area to Yellowknife city. Plans are also underway to construct a deep water port in Bathurst Inlet (Monro et al 360), and this will help in opening up the area to the rest of Canada. Diavik mine has also constructed an airport with a 1596 long gravel runway (Monro et al 359).

Given the fact that the mines need electricity to operate, power transmission has really improved in this region. The industry also sponsors other services such as medical facilities, sports centres among others.

But it is erroneous to assume that these companies have the interests of the aboriginal communities at heart when embarking on all these initiatives. Initiatives such as transport network are aimed at increasing the profitability of the mines by making access to the markets easier, and supply of labour more convenient.

Facilities such as medical and sports are aimed at keeping the workforce for the mines healthy and strong, ensuring that diseases do not affect the production of the mines.

Economic Prosperity

The climate of northern Canada is so harsh, and as such unable to support farming. The area is also very remote, and has a very small population density, making trade unviable. However, the fact that the region is endowed with natural resources has made the local community to turn to the mineral industry, making this one of the most important source of livelihood in this region.

It is estimated that, since the inception of economic mineral exploration in this area in late 1970s, mineral wealth in excess of $34 billion has been realised (Kaarina 77). Analysts are of the view that a third of this wealth base emanates from diamond mining, making it one of the most significant source of livelihood for the community.

Production of diamond in the whole of Canada has realised more than $12 billion of wealth (Kaarina 66). In the Northwest Territories, this industry has invested approximately $10 billion, and this has gone to capital and operational expenditures. More than fifty percent of this has been used on northern and aboriginal economic ventures.

A case study of Northwest Territories will reveal the significance of the diamond mining industry in this region. This activity makes up more than forty percent of this region’s GDP (Prno et al 9).

Impact Of Diamond Mining To The Region’s Physical Environment: A Case Study Of Yellowknife City

Yellowknife City: An Overview

This town is both the capital and largest city of the Northwest Territories, strategically located on the northern shores of the Great Slave Lake (Bastedo 38). The area was first settled in the year 1935, and this is after prospectus discovered gold in the region (Bastedo 38). Soon after, this town will become the economic base of this territory, and capital city in late 1960s.

The significance of this city as a mining centre was revived with the discovery of diamonds in early 1990s. Diavik mines followed in 2003, and in 2004, the two mines produced more than 12,618,000 carats of diamond (Doem & Kinder 52). This consignment was worth more than 2.1 billion Canadian dollars.

Yellowknife City and Diamond Mining

From 1991, when commercial exploitation of diamond resources in this region began, many changes have taken place. For example, the area has been isolated geographically for the longest time. But the transportation sector has since been upgraded. For example, the Yellowknife Airport is one of the significant in northern Canada (Smith 12).

The airport has been used a great deal by the mining industry to transport diamonds to the market and bring in supplies. It has also been instrumental in bringing in labour from the larger Canada and from other parts of the world.

The population of the city has increased with the rise in mining activity. In 2009, 19,711 people were living in the city, making it one of the densely populated regions in northern Canada (Prno et al 3). As of 2006, about 22 percent of the population was made up of indigenous communities. This means that the area has experienced an influx of outsiders, who have been attracted by the diamond mines in the area.

The Negative Impacts Of Diamond Mining In Northern Canada

Overview

Most people argue that the mining business in this part of the world is not as glamorous as the gems extracted from the bowels of the earth. This supports the thesis statement of this paper, which hypothesises that the indigenous community has not significantly benefited from the mining ventures.

Impact of Diamond Mining on the Region’s Wildlife

The indigenous community in northern Canada has traditionally relied on the caribou for survival. However, the mines have affected the Bathurst caribou herd, a significant source of livelihood for many communities in this region. For example, approximately 350,000 caribou in Bathurst use the diamond mine fields as their migration routes (Doem & Kinder 51).

Mines such as Diavik cover a paltry 0.03 percent of this space. However, a combination of many mines in this area will surely affect the population of the caribou. This is given that explorers have discovered more diamond deposits under the animal’s migration grounds.

This being the case, it might be argued that the welfare of the northern communities may be negatively affected in the future. This is especially so after the deposits are exhausted, and the miners leave in their wake large swathes of waste land.

Impact of Mining on the Environment

The extraction methods that are adapted by this industry may sometimes be harmful to the environment. This is especially so given the fragile nature of the northern environment. There have been cases of lakes been drained in order to reach kimberlite pipes on the seabed. This destabilises the marine wildlife, which is a major source of livelihood for the locals.

Other mining techniques such as open pit methods bare large swathes of land, destroying trees and interfering with the natural topography. This affects the wildlife on the ground, for example blocking migration routes of animals that are used as source of food by the aborigines.

Dumping of large quantities of dirt on the ground to make room for the mining equipment also affects the ground layout of the area. A case in point is the Gahcho Rue Mine, which displaced large herds of caribou from their natural habitat (Muise & McIntosh 70).

While this mine is credited with the production of more than 600,000 carats of this gem per annum, it also produces more than 2 and a half million tonnes of waste dirt annually. It also drains more than 40 Olympic sized pools of salt water to the adjacent Attawapiskat River on a daily basis, further raising concerns of environment degradation by these mines (Prno et al 8).

The mines also use chemicals in their processes, and these somehow find their way to the environment. For example, in 2004, the Ekati mine was found to have raised chemical levels in the surrounding lakes, while more than 19 square kilometres of natural habitat was lost to the mine (Doem & Kinder 54).

Conclusion And Recommendations

From these arguments, it is obvious that the aboriginal communities may be affected negatively by the mining taking place in the area. Most of the mining companies are owned by foreigners. For those that are owned by local Canadians, it is most likely that they are not members of the aboriginal communities.

This means that most of the wealth taken from the mines is repatriated by the investors. The locals are left with little or nothing at all, and the environment is affected negatively.

Most of the initiatives that are undertaken by the mining companies are ostensibly aimed at improving the lives of the locals. But in reality, the initiatives are meant to benefit the mining companies.

For example, sponsoring students from the aboriginal communities is meant to create a more skilled labour force for the mines. Training the community on conflict resolution skills ensures that the members of the community are not tied down by conflicts, and they are available to work for the mines.

However, there are ways that the local community can ensure that they benefit more from the diamond mining industry. The following are some of the recommendations to this end:

- Sensitise the community members on their right to be involved in the exploitation of resources that are in their territory. This way, they will share on the benefits derived from the exploitation, raising their quality of life more.

- The Canadian government should come up with strategies that ensure that the benefits of the mines are sustainable in the community. For example, the community should be empowered so that they may continue with their life uninterrupted even after the closure of the mines.

- Environmental bodies should ensure that the mining companies adhere to laid down rules and regulations that ensure that they safeguard the environment.

- The mining companies should ensure that the interests of the local communities are taken into consideration in their operations. Corporate social responsibility initiatives should be tailored such that they benefit the community and not the mining company only.

Works Cited

Bastedo, Jamie. Yellowknife Outdoors – Best Places for Hiking, Biking, Paddling, and Camping. Calgary: Red Deer Press, 2007.

Britton, John. Canada and the Global Economy: The Geography of Structural and Technological Change. Ontario: McGill-Queen’s Press, 1996. Print.

Doem, Gregory & Kinder, James. Strategic Science in the Public Interest: Canada’s Government Laboratories and Science-Based Agencies. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2007. Print.

Gibson, Ginger & Klinck, Jason. “Canada’s Resilient North: The Impact of Mining on Aboriginal Communities”. Pimatisiwin: A Journal of Aboriginal and Indigenous Community Health, 3(1); 2008.

Greig, Kelly. Considering the Costs of Canada’s Diamonds. Canadian Geographic. 2011. Web.

Kaarina, Stiff. “Cumulative Effects Assessment and Sustainability: Diamond Mining in the Slave Geological Province.” University of Waterloo, Ontario Canada, 2001.

Monro, James. Wicander, Reed & Hazlett, Richard. Physical Geology: Exploring Earth. New York: Cengage Learning, 2006. Print.

Muise, Delphin & McIntosh, Robert. Coal Mining in Canada: A Historical and Comparative Overview. Ottawa: National Museum of Science and Technology, 1996. Print.

Prno, Jason. Bradshaw, Ben & Lapierre, Dianne. “Impact and Benefit Agreements: Are they Working?” CIM, 2010.

Santarossa, Bruna. Diamonds: Adding Lustre to the Canadian Economy. Statistics Canada. 2009. Web.

Smith, Jeremy. “The Growth of Diamond Mining in Canada and Implications for Mining Productivity”. Centre for the Study of Living Standards, 2004.

Wilkes, James. The Role of Integrated Environmental Impact Assessment for Mining Projects in Canadian Aboriginal Communities: A Systematic Literature Review of Current Trends and Challenges. Trent University. 2008. Web.

World Diamond Council. Diamond Mining and the Environment Fact Sheet. World Diamond Council. 2008. Web.