Charlotte Perkins Gilman was born in Hartford, Connecticut, on July 3, 1860. She is best known for her short story, The Yellow Wall-Paper (1892), and her treatise, Women and Economics (1898). The author believed in equal rights, being greatly influenced and inspired by the women’s suffrage movement. Her death was a suicide in Pasadena, California, on August 17, 1935.

Read the full Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s biography prepared by our editorial team to find out more!

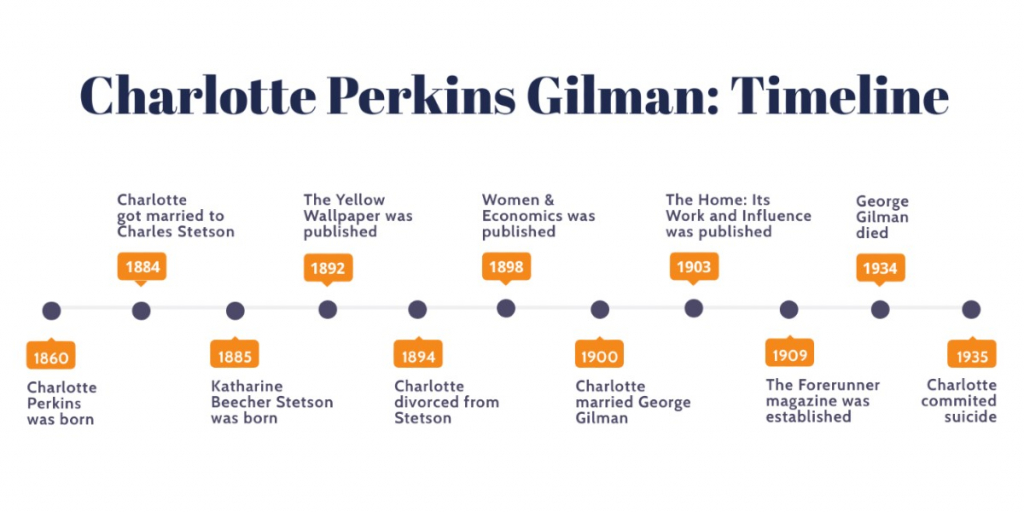

📈 Charlotte Perkins Gilman: Timeline

Below is the timeline of Charlotte Perkins Gilman. It reflects the most important events of the writer’s life.

👪 Charlotte Perkins Gilman: Early Years

Charlotte Perkins Gilman was a second child in the Perkins family, born on July 3, 1860. Her lineage included women who Gilman was influenced and inspired by. They were Harriet Beecher Stowe, a noted novelist; Catherine Beecher, a women’s higher education advocate; and Isabella Beecher Hooker, a suffrage movement leader.

Mr. Perkins abandoned the family in Charlotte’s early years, so Mrs. Perkins was left at her relatives’ pity, moving with children from house to house and living in poverty. Gilman received little to no formal education. Still, she had the opportunity to support herself by designing greeting cards after attending the Rhode Island School of Design for two years (1878-1880).

💑 First Marriage

In 1884, a 24-year-old Charlotte married Charles Walter Stetson, an aspiring artist. She gave birth to their only child, Katharine Beecher Stetson, the following year. After that, Gilman suffered from postpartum depression, which nearly drove her to the edge. To treat her “neurasthenia,” Dr. Silas Weir Mitchell implemented the infamous “rest cure,” the newest invention of his. This treatment prohibited the patient from moving around, talking, and doing anything, not even reading. Instead, the patient was to lie in bed and eat a lot, and that’s it.

After a month of such a lifestyle, Gilman went home and tried to follow the rest of the “noted specialist’s” prescription.

“Live as domestic a life as possible. Have but two hours’ intellectual life a day. And never touch a pen, brush, or pencil as long as you live.”

This almost drew Gilman insane. Divorces were a rare occasion in the 19th century, but as Gilman later wrote, “It was not a choice between going and staying, but between going sane, and staying insane.” This experience influenced and inspired Charlotte Perkins Gilman to write her best-known story: The Yellow Wallpaper.

♀️ Women’s Rights Activism

After the separation, Charlotte Perkins Gilman and her daughter moved to Pasadena, California. There, the author became an accomplished writer. She was known for writing plays, poetry, fiction, and non-fiction works and was published in progressive magazines. Gilman also became active as a women’s rights advocate. The author lectured about feminist theory, social reforms, and how the traditional domestic environment was oppressive to women.

One of the best-known non-fiction works of Gilman is a treatise, Women and Economics (1898). There, the author expressed the belief that women will gain true independence only when they have economic freedom. The themes explored in Gilman’s lectures and papers on economics and sociology translate into her fiction. For instance, in the short story If I Were a Man (1914), Gilman revealed the thoughts of a young woman who craved to be a man. When the heroine suddenly became her husband, she experienced a perspective entirely different from hers. In 1915, Gilman wrote Herland, a novel exploring a utopian world composed entirely of women, with an ideal social order free of conflict, war, and domination.

Gilman established The Forerunner (1909-1916), a magazine where she expressed her ideas on feminism and social reform.

👵 Later Years

Charlotte Perkins Gilman wanted her daughter, Katharine, to get to know her father, Stetson. Gilman’s ex-husband was remarried to her close friend, Grace Ellery Channing. In 1894, the girl arrived to be raised by the pair. That was an unorthodox decision for the time, but Gilman was of progressive views on parental rights. After that, Gilman married her first cousin, George Houghton Gilman, in 1900. When he died in 1934, Gilman went back to California to be close to her daughter.

Charlotte Perkins Gilman: Suicide

Two years before her husband’s death, in 1932, Charlotte Perkins Gilman was diagnosed with inoperable breast cancer. Being a euthanasia advocate, Gilman, aged 75, took her life with a chloroform overdose in 1935. In her last letter, she stated that she “preferred chloroform to cancer.” Her suicide note read:

“When all usefulness is over, when one is assured of unavoidable and imminent death, it is the simplest of human rights to choose a quick and easy death in place of a slow and horrible one.”

📚 Charlotte Perkins Gilman: Bibliography

Non-Fiction

- Women and Economics: A Study of the Economic Relation Between Men and Women as a Factor in Social Evolution (1898)

- Concerning Children (1900)

- The Home: Its Work and Influence (1903)

- Human Work (1904)

- The Man-Made World; or, Our Androcentric Culture (1911)

- Our Brains and What Ails Them (1912)

- Humanness (1913)

- Social Ethics (1914)

- The Dress of Women (1915)

- Growth and Combat (1916)

- His Religion and Hers: A Study of the Faith of Our Fathers and the Work of Our Mothers (1923)

- The Living of Charlotte Perkins Gilman: an Autobiography (1935)

Fiction

- The Yellow Wallpaper (1892)

- What Diantha Did (1910)

- Moving the Mountain (1911)

- The Crux (1911)

- Benigna Machiavelli (1916)

- Herland (1915)

- With Her in Ourland (1916)

- Unpunished (1997)

Poetry

- In This Our World (1893)

- Suffrage Songs and Verses (1911)

💬 Charlotte Perkins Gilman: Quotes

There is no female mind. The brain is not an organ of sex. As well speak of a female liver.

Women and Economics, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Chapter VIII

This quote is from Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s famous treatise, Women and Economics, that she wrote in 1898. It calls for a radical social reform concerning the domestic servitude of women and necessitates women’s economic independence. Gilman theorizes that such social responsibilities as domestic chores and child-care are to be designated to people suited and trained for this work.

The first duty of a human being is to assume the right functional relationship to society – more briefly, to find your real job, and do it.

An Autobiography, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Chapter IV

This quote is from Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s The Living of Charlotte Perkins Gilman: an Autobiography, which she wrote in 1935. It translates Gilman’s idea of the absolute necessity for a person of any gender to express themselves by assuming a role in society and carrying out their duties, day after day. Otherwise, the person will inevitably degrade, or worse, go mad.

Death? Why this fuss about death? Use your imagination, try to visualize a world without death! Death is the essential condition of life, not an evil.

An Autobiography, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Chapter IV

This quote is from Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s The Living of Charlotte Perkins Gilman: an Autobiography written in 1935. It colors death as a natural part of life, which shouldn’t be regarded with such fear as it often is.

…when all usefulness is over, when one is assured of unavoidable and imminent death, it is the simplest of human rights to choose a quick and easy death in place of a slow and horrible one.

Suicide Note, Charlotte Perkins Gilman

This quote is from Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s suicide note written in 1935. It translates Gilman’s advocacy for euthanasia, the person’s freedom to choose whether they live or die, and the person’s right to have agency over their life.