Introduction

Company Overview

The current coursework focuses on the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences (hereinafter referred to as the Faculty) of Swansea University (hereinafter referred to as the University). The University is a research-led institution that generates significant outcomes in the spheres of culture, health, wealth, and social development (Swansea University, n.d.a). One should clarify that the Faculty “is home to a welcoming and inclusive community that pursues scholarship, research, and innovation that benefits society, and which promotes a student experience” (Swansea University, n.d.b, para. 1). Thus, the company draws sufficient attention to research and requires innovative solutions to promote scientific activities and share results, and the current coursework focuses on these issues.

Nature of the Challenge

The coursework is a Faculty-specific add-on to the successful AgorIP Open Innovation project. In turn, AgorIP is a platform that a scientist can use to seek assistance in finding professional service contractors who can help them to deliver their projects (AgorIP, 2018). AgorDawn is implemented to drive commercialization and encourage the Faculty staff to engage in research and share their results and knowledge with an external audience. When it comes to sharing research outcomes, a barrier exists regarding the misconception of commercialization because staff members do not want to be blamed for a focus on capitalism and profit-making (Cole et al., 2021). Another barrier refers to organizational features that include the lack of sufficient resources, time pressure, and workload (Yousefi & Abdullah, 2019). All these barriers result in the fact that the Faculty staff members tend to avoid dealing with AgorDawn to publish their research findings.

Contact with the Company

It is necessary to highlight that the University has actively participated in the project. First of all, the organization quickly approved the coursework so that the scientific process could start. Simultaneously, the Faculty members willingly engaged in the project and gave their time to answer interview questions. It is challenging to overestimate the importance of the company’s contribution to the coursework because the organization supported and promoted the research efforts to investigate the issue under analysis.

Market Analysis

Market Overview

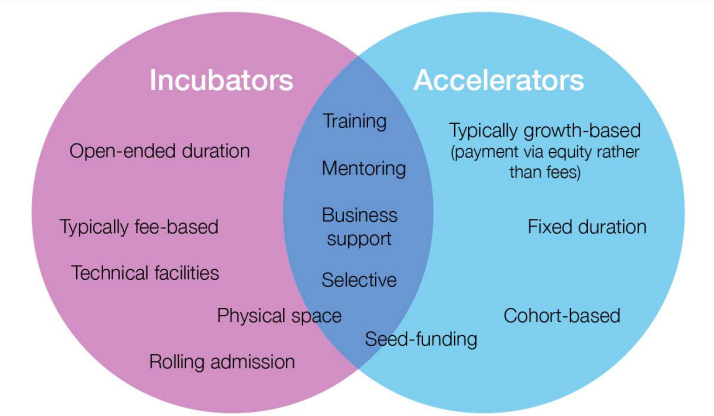

AgorDawn operates within the sphere of business and research incubators and accelerators. It is now reasonable to explain what these facilities mean and how the platform under analysis refers to them. On the one hand, research incubators are physical workspaces “with the addition of some shared facilities and business support services, such as mentoring, training, and access to investors” (Bone et al., 2019, p. 9). These facilities feature open-ended duration and are typically fee-based. On the other hand, accelerators “offer their services through an intensive cohort-based program of limited duration (usually 3-12 months) and typically focus on services over physical space” (Bone et al., 2019, p. 10). Accelerators are growth-based, which denotes that payment amounts depend on equity (Bone et al., 2019). Figure 1 by Bone et al. (2019) presents the characteristic features of these two facilities. This visual allows for assessing the functionality of the facilities.

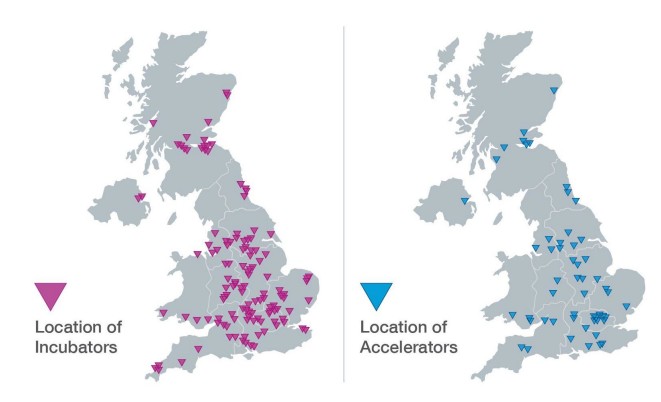

It is now rational to explain how AgorDawn relates to its competitors in the market. The platform has a significant advantage because it is not limited to physical facilities. Beresford (n.d.) highlights that the provision of physical spaces is a characteristic feature of accelerators and incubators. According to Bone et al. (2017), there were 205 incubators and 163 accelerators in the UK in 2017. However, these figures were not stable, and the quantity increased in 2019 (Bone et al., 2019). This information demonstrates that the UK offers a supportive environment for these facilities to emerge and operate. Figure 2 by Bone et al. (2019) depicts that accelerators and incubators are relatively evenly distributed across the UK. However, it is still true that the facilities are typically found in locations close to institutions and business parks (Hassan, 2020). That is why AgorDawn offers a significant advantage for scientists.

Appropriate Theories

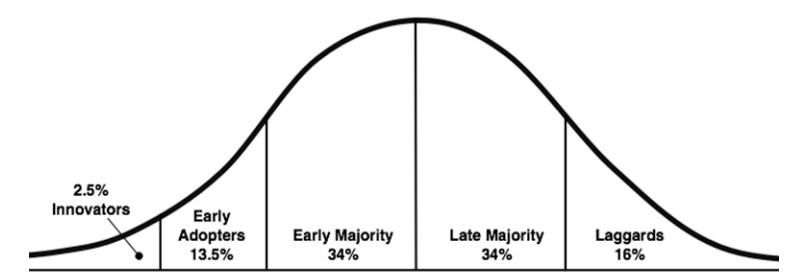

Various theoretical assumptions can be used to understand how and why AgorDawn was introduced into the market. Firstly, it is reasonable to look at the Diffusion of Innovation Theory developed by E. M. Rogers in 1962 (Boston University School of Public Health, 2019). This framework divides technology adopters into five categories, and Figure 3 depicts the adoption curve. It is rational to explain the visual:

- Innovators: these people are willing to start using new technologies;

- Early Adopters: they are opinion leaders and use innovations because of the need to introduce improvement;

- Early Majority: they start relying on innovations when they are aware of their benefits;

- Late Majority: they are skeptical of innovation and only use it when the majority proves its effectiveness;

- Laggards: these individuals are very conservative and require strong statistics and facts to believe that new technologies are worth considering (Boston University School of Public Health, 2019).

This theoretical assumption explains why some employees are more willing to use AgorDawn.

Secondly, it is reasonable to look at the university-business-government collaboration (UXC) approach. According to Nyman (2015), a traditional approach stipulates that the ethos and culture of scientific endeavor traditionally motivated academics to engage in research practices. However, the current environment has brought some changes, which denotes that research is often promoted by economic and competitive factors (Nyman, 2015). This finding reveals that the modern world deals with a new emerging model of innovation and commercialization of research projects. That is why AgorDawn represents a unique and suitable environment that meets the current trends and facilities scientific activities.

Thirdly, one should highlight that much theoretical information proves that research incubators imply various advantages. According to Kain et al. (2014), these facilities are an environment that is supported by universities to promote innovation among scholars and students. Van Weele et al. (2020) support this statement and add that incubators “have become one of the most prominent instruments for facilitating the survival and growth of innovative startups” (p. 984). These findings allow for the suggestion that these facilities often result in significant projects that produce knowledge with practical importance. Thus, AgorDawn is an example of such an incubator that, simultaneously, offers specific benefits introduced by online technologies and the absence of fees.

Aims and Objectives

Project Aim

The coursework focuses on encouraging the Faculty staff members to share their knowledge and research with a wide audience in a way that is beneficial for all the stakeholders. This aim denotes that the project attempts to ensure that research findings are more available to an external audience, which will popularize science and the University among scholars. The following sub-section will present the SMART objectives that specify what outcomes the coursework plans to achieve.

SMART Objectives

The SMART objectives are needed to ensure that the project has specific and achievable goals.

- Objective 1: To identify at least two relevant obstacles facing research incubators such as AgorDawn by the end of September 2022.

- Objective 2: To critically analyze the market environment where AgorDawn operates and identify at least two relevant threats and two opportunities and determine whether the use gap is a case for AgorDawn by the end of September 2022.

- Objective 3: To develop strategic recommendations based on marketing to enhance the participation of the University staff in the AgorDawn project by the end of September 2022.

These objectives demonstrate that the coursework, generally speaking, focuses on the aspects that accompany the implementation of AgorDawn.

All Tasks

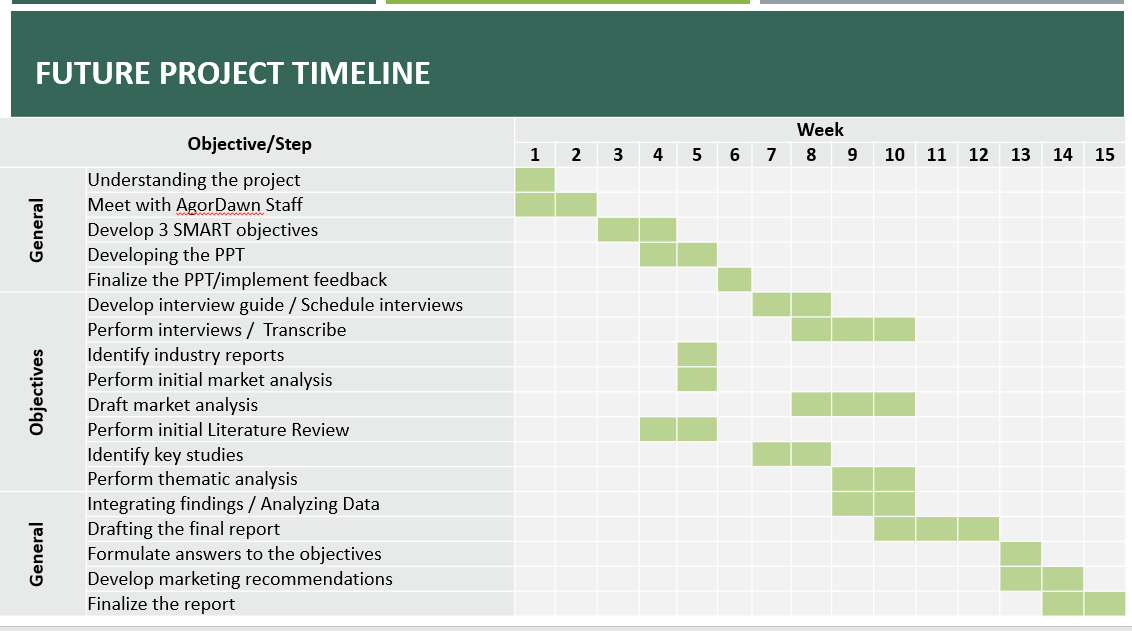

The leading aim and the three objectives above represent the main project goals, while specific tasks to perform will be presented below. The project is implemented individually, which denotes that its author is responsible for completing all the stipulated tasks. Figure 1 below presents a Gantt chart that highlights the individual steps needed to implement the project and their timeline, which allows for understanding the project delivery.

Figure 1 demonstrates that it took 15 weeks to complete the coursework. Week 1 was needed to understand the project, while two weeks were suitable to meet with AgorDawn staff. Weeks 3 and 4 witnessed as the 3 SMART objectives were developed. Furthermore, a PowerPoint presentation and the initial literature review were prepared during Weeks 4 and 5. Week 5 was suitable for identifying industry reports and performing an initial market analysis. The PowerPoint presentation was finalized with the incorporation of the feedback during Week 6. Weeks 7 and 8 were productive because the interview guide was developed, and the interviews themselves were scheduled. Simultaneously, key literature sources and studies were identified during the same period.

Performing interviews and transcribing them was a challenging task that required many resources, which justified the fact that the task was performed during Weeks 8-10. In parallel with this task, the market analysis was drafted. It took Weeks 9 and 10 to perform the thematic analysis and analyze the identified data to integrate the findings. Weeks 10-12 witnessed that the coursework’s author dealt with drafting the final report, which implied drawing attention to the project’s content, grammar, and style. Answers to the objectives were formulated during Week 13, and this activity was significant because it revealed whether the project met its goals. Market recommendations were formulated during Weeks 13 and 14 to explain how research could be promoted. Finally, it took Weeks 14 and 15 to finalize the report.

Research and Methodology

Primary Research

The coursework relies on various data sources, and primary research is significant. Semi-structured interviews were used to collect data from members of the Faculty. The given instrument was selected because this approach follows a previously developed protocol and allows for additional discovery, which denotes that researchers are free to ask additional questions when they consider it necessary (Magaldi & Berler, 2020). This strategy guarantees that the obtained answers can present an in-depth discussion of an issue under analysis. The project’s aim and SMART objectives guided the interview creation, which denoted that questions were developed to find out how faculty members assessed AgorDawn. It is possible to find the questions in Appendix A. Once the answers were obtained, thematic analysis was manually performed to discover meanings and identify the existing trends in using the software application (Braun & Clarke, 2006). These steps demonstrate that the coursework relied on a promising methodology to deal with primary research.

Secondary Research

In addition to that, the report relies on secondary research to compare the findings from the interviews with the existing knowledge. Secondary data was used similarly to the work by Kain et al. (2014) because these scholars performed a high-quality study to analyze the role of research incubators. Multiple sources were used to locate appropriate data for the coursework. On the one hand, the report relied on the UK government reports (GOV.UK) to identify how the sphere of research incubators and accelerators was developed. These sources were chosen because they were the most reputable in presenting this information, and links to a few reports are found in Appendix B. On the other hand, a systematic analysis of scholarly articles was performed to determine what experts stated about the issue under analysis. Appropriate works were extracted from reputable and professional journals that were accessed via Google Scholar.

Ethics of Primary Research

Specific steps were taken to ensure that primary research was free from ethical issues. The respondents signed informed consent to state that they were familiar with research objectives and processes (Husband, 2020). Simultaneously, the participants were instructed that they could stop answering questions at any time, which demonstrated that they voluntarily engaged in the project (Josephson & Smale, 2021). Data confidentiality was ensured because the responses were not sent to any third parties. The chief researcher reviewed and transcribed them, while manually written copies would only be stored in the investigator’s computer. Simultaneously, the responses were coded, which implied that every answer was headed using numbers from “1” to “4.” This step was necessary to ensure that the analysis was confidential and unbiased. All these measures were obligatory to prove that the project would not result in any harm to the participants. All this information demonstrates the primary research methodology relied on the Data Protection Act 2018 requirements (GOV.UK, n.d.). This UK’s interpretation of the General Data Protection Regulation ensures that primary research is fair, lawful, adequate, and unbiased.

Ethics of Secondary Research

Secondary research processes did not involve any ethical issues that could impact the entire project. It was not necessary to receive informed consent from articles’ and report’s authors before using these resources in the coursework. Secondary research dealt with data that was easily accessible on the Internet. Furthermore, it is worth admitting that the project included articles if their full texts were accessible. These procedures demonstrate that no ethical issues could affect the process.

Risks

It is reasonable to admit that various risks could impact project implementation. Firstly, it was necessary to ensure that credible and timely data was used. That is why the focus was placed on working with government reports and evidence from scholarly sources. Secondly, there existed a risk that the chief investigator could miss a significant concept from the existing literature or from the interviews. Thus, the double-checking principle was strictly followed while working on the project.

Delivery

Four interviews were performed to collect data from the Faculty staff members. These individuals were selected because they had some experience in working within the research field and voluntarily agreed to participate in the project. These respondents were interviewed using Skype and according to the plan presented in Appendix A. Once the answers were obtained, it took a few weeks to transcribe them, which was necessary to make the answers friendly for thematic analysis. According to the determined objectives, there were created four themes with appropriate codes, including 1 – Obstacles, 2 – Threats, 3 – Opportunities, and 4 – Strategic Recommendations. These answers were then analyzed to determine where the themes are present in the responses, and the obtained results are presented in Table 1 below.

Table 1: The Presence of Themes in the Responses

Table 1 demonstrates that the respondents more frequently talked about opportunities that AgorDawn could bring. These possibilities include providing support, promoting innovation and engagement, making research commercialized, and providing accessibility. Obstacles represent the second popular theme, and the individuals admitted that the platform was underutilized because it lacked the popularity and was scary for academics who did not want to equal research to profit making. The respondents acknowledged that similar platforms from Oxford, Sheffield, Cardiff, and other universities represented the main Threats to AgorDawn. Finally, it was possible to improve the situation with the help of Strategic Recommendations. They included socializing the platform, using meetings to help staff understand its meaning, and reckon on the government impact to make the platform use more widespread. This fact demonstrates that staff members understand the importance of using the platform, but numerous obstacles and threats lead to the use gap.

Objective 1: Obstacles

This objective focuses on finding research incubators’ obstacles, and three essential barriers were obtained from the primary research above. Now, one should identify what the existing literature says about these barriers. A mixed-method study of three universities in Brazil identified that resistance to commercialization prevented employees from dealing with research incubators (Thomas et al., 2021). It was found during the interviews that this obstacle was an issue for AgorDawn. Another scholarly article utilizes Rogers’s theory of adaptation and determines that staff members can avoid using research incubators and accelerators because many people typically resist changes (Porter & Graham, 2016). Simultaneously, respondents of scientific interviews indicated that they were likely to utilize innovative approaches when they trusted them (Milwood & Roehl, 2018). Another scientific study stipulates that the use of research incubators and accelerators can be low because of disadvantaged economic conditions that prevail in a particular area (Rodríguez‐Pose & Wilkie, 2019). Finally, a scientific article by Fischer et al. (2018) mentions that a significant obstacle refers to the fact that some accelerators and incubators offer poor access to capital. The last two obstacles are irrelevant to the AgorDawn case.

Objective 2: Threats and Opportunities

Numerous scholarly articles comment on what opportunities and threats are associated with research incubators and accelerators. These institutions can promote research, and its results can lead to solving the existing social and other problems (Thomas & Pugh, 2020). Simultaneously, scientists indicate that incubators are effective because they create effective networks that facilitate cooperation among various stakeholders and offer financial and other support (Nieth, 2019; Siddiqui et al., 2021; Alpenidze et al., 2019). Another positive aspect refers to the fact that these institutions lead to open innovation, which can lead to significant improvement in various spheres (Hausberg & Korreck, 2021). Finally, Chase and Webb (2018) acknowledge that incubators and accelerators lead to short and long-term benefits for individuals and organizations. Among the selected studies, only one of them commented on what threats could affect the use of accelerators and incubators. Lukosiute et al. (2019) mention that working in cooperation with other stakeholders within incubators can put intellectual property at risk. These findings reveal what threats and opportunities impact the use of accelerators and incubators.

Objective 3: Strategic Recommendations

It is possible to extract some strategic recommendations from the existing literature. Firstly, Wakkee et al. (2019) stipulate that active and effective implementation of research incubators and accelerators depends on leadership. This statement denotes that organizations should find and develop leaders that will promote collective action. Secondly, Radinger-Peer (2019) explains that appropriate policy actions are needed to make stakeholders actively refer to the resources under analysis. It is reasonable to issue specific regulations that will motivate individuals and organizations to deal with incubators and accelerators. However, this measure can be taken if all the identified obstacles are addressed.

Evaluation

It is possible to mention that the research project has successfully coped with the stipulated tasks, which has allowed for meeting the overall aim and SMART objectives. Objectives are considered satisfied because the primary and secondary research activities have resulted in finding the required information. The respondents willingly participated in the interviews and answered the predetermined questions, while the interviewers asked additional questions to delve deeper into the topic. The project is of high quality because the interviewees and experts rely on the same aspects to answer the questions. For example, some respondents stipulated that some opportunities include providing support and promoting innovation, while Nieth (2019), Siddiqui et al. (2021), and Alpenidze et al. (2019) mentioned the same. Thus, one can suggest that the project is worth considering because it has revealed the connection between scientists’ and practitioners’ points of view regarding the use of research incubators and accelerators.

Even though the respondents and the literature articles have drawn various levels of attention to different aspects, including obstacles, threats, opportunities, and strategic recommendations, sufficient information was located to meet the objectives. The rationale behind this statement is that the project has located over two obstacles (Thomas et al., 2021; Porter & Graham, 2016), two threats (Lukosiute et al., 2019), over two opportunities (Thomas & Pugh, 2020; Hausberg & Korreck, 2021), and valuable strategic recommendations (Wakkee et al., 2019; Radinger-Peer, 2019). This information denotes that the overall aim is met because the project explains why Staff members deal with accelerators and incubators while others avoid cooperating with them. Thus, these findings have practical meaning because organizations can maximize opportunities and eliminate obstacles and threats to make incubators and accelerators more widely used.

However, one should admit that the qualitative methodology can only identify the threats, obstacles, opportunities, and recommendations. This information denotes that the project does not comment on which specific aspects are the most impactful. It is necessary to conduct a different study using a quantitative method to rate the effect of the identified barriers and opportunities. Thus, this project is worth considering because it contributes to further research.

In conclusion, it is worth stating that the project has created versatile stakeholder value. Firstly, its benefit refers to awareness raising among potential users. As interviewees mention, the AgorDawn platform was underutilized because not all staff members were aware of it, while others were afraid of using the service. The same conclusion was found in the literature because the absence of trust in new technology can significantly limit its use rate (Milwood & Roehl, 2018). Secondly, the project is going to result in significant social advantages. If the AgorDawn platform is actively utilized by the Staff members, they will create more studies. The latter, in turn, are expected to generate valuable knowledge that can bring essential improvement in the social sphere. That is why there is no doubt that the project can be beneficial for individuals and the entire community because experts obtain an opportunity to engage in research and generate valuable knowledge.

Conclusions

The given research project has found that AgorDawn is an effective platform to increase research activities among university staff members and make these individuals share their findings with the general public. Even though this resource seems needed and beneficial, it often remains underutilized. That is why the present project has been implemented to determine what obstacles, threats, and opportunities are associated with the use of research accelerators and incubators. Primary and secondary research activities have been utilized to find the required information. According to the interviewees and authors of scholarly studies, there are many factors that can either motivate or prevent individuals from dealing with research incubators and facilitators. Organizations should keep these findings in mind to increase the AgorDawn use rate and ensure that more staff members are willing to work with the platform.

The project provides society with both theoretical and practical significance. On the one hand, the paper has identified, analyzed, and synthesized evidence from many scholarly articles on the selected topic. That is why the project presents the current state of research regarding the implementation of research incubators and accelerators. On the other hand, the project is helpful because it reveals the most significant aspects that hinder or promote the use of AgorDawn. That is why the selected organization can refer to the findings to increase the use rate, while other institutions also can use the results to facilitate the implementation of different accelerators and incubators.

Recommendations

Since a particular use gap has been identified, it is reasonable to offer specific recommendations on how to make staff members use AgorDawn more actively. Firstly, Participant 1 (Appendix C) mentions that it is necessary to socialize the platform better. This suggestion implies that not all stakeholders are aware of this resource and its opportunities. It is possible to create a specific marketing campaign to advertise AgorDawn and explain why this platform is better than competitive accelerators and incubators that are scattered across the UK (Bone et al., 2019). The current project is a significant step toward raising awareness of the public regarding AgorDawn and its advantages. Numerous online sources are suitable means to market the platform.

Secondly, organizations should take practical steps to prove that their employees understand what AgorDawn is. Participants 1 and 4 (Appendix C) stipulate that it is reasonable to organize regular meetings where experts explain why this platform deserves attention. These events seem effective because they guarantee that many interested individuals will discover about AgorDawn within a limited period of time. These stakeholders can ask questions during these meetings, which will improve their knowledge of the given research accelerator. That is why the University should consider organizing these events on a regular basis to improve the utilization rates of AgorDawn.

Thirdly, the meetings can be more successful if the organizations have effective leaders who are interested in research accelerators and incubators. According to Wakkee et al. (2019), leaders are significant because they can promote collective action. For example, if a leader is aware of AgorDawn and understands its benefits, this person can motivate and make others deal with the given platform. That is why organizations should contribute to leader development since such individuals can essentially help increase AgorDawn use rates.

Fourthly, one should remember that AgorDawn and other research accelerators and incubators can generate essential benefits for the entire community. That is why it is reasonable to expect that the government can make a specific effort to promote the use of such platforms. In particular, Radinger-Peer (2019) stipulates that appropriate policy changes are needed to prove that more organizations and institutions actively cooperate with these accelerators and incubators. Simultaneously, Participant 1 (Appendix C) acknowledges that the government can improve the given state of affairs by issuing regulations that will popularize AgorDawn. All these four recommendations can address the use gap and make research incubators and accelerators more requested.

References

AgorIP. (2018). What we do. Web.

Alpenidze, O., Pauceanu, A. M., & Sanyal, S. (2019). Key success factors for business incubators in Europe: An empirical study. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 25(1), 1-13.

Beresford, K. (n.d.). New report. Incubators and accelerators in the UK. Enterprise Educators. Web.

Bone, J., Allen, O., & Haley, C. (2017). Business incubators and accelerators: The national picture. Department for Business, Energy, & Industrial Strategy. Web.

Bone, J., Gonzalez-Uribe, J., Haley, C., & Lahr, H. (2019). The impact of business accelerators and incubators in the UK. Department for Business, Energy, & Industrial Strategy. Web.

Boston University School of Public Health. (2019). Diffusion of innovation theory. Web.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101.

Chase, T., & Webb, J. (2018). Business incubator and accelerator sustainability. Business Innovation and Incubation Australia, 1-36.

Cole, C. L., Sengupta, S., Rossetti, S., Vawdrey, D. K., Halaas, M., Maddox, T. M., Gordon, G., Dave, T., Payne, P. R. O., Williams, A. E., & Estrin, D. (2021). Ten principles for data sharing and commercialization. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 28(3), 646-649. Web.

Fischer, B. B., Queiroz, S., & Vonortas, N. S. (2018). On the location of knowledge-intensive entrepreneurship in developing countries: Lessons from São Paulo, Brazil. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 30(5-6), 612-638. Web.

GOV.UK. (n.d.). Data protection. Web.

Hassan, N. A. (2020). University business incubators as a tool for accelerating entrepreneurship: Theoretical perspective. Review of Economics and Political Science, 1-20. Web.

Hausberg, J. P., & Korreck, S. (2021). Business incubators and accelerators: A co-citation analysis-based, systematic literature review. Journal of Technology Transfer, 45, 151-176. Web.

Husband, G. (2020). Ethical data collection and recognizing the impact of semi-structured interviews on research respondents. Education Sciences, 10(8), 206. Web.

Josephson, A., & Smale, M. (2021). What do you mean by “informed consent”? Ethics in economic development research. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 43(4), 1305-1329. Web.

Kain, V. J., Hepworth, J., Bogossian, F., & McTaggart, L. (2014). Inside the research incubator: A case study of an intensive undergraduate research experience for nursing & midwifery students. Collegian, 21(3), 217-223. Web.

Lukosiute, K., Jensen, S., & Tanev, S. (2019). Is joining a business incubator or accelerator always a good thing? Technology Innovation Management Review, 9(7), 5-15.

Magaldi, D., & Berler, M. (2020). Semi-structured interviews. Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences, 4825-4830. Web.

Milwood, P. A., & Roehl, W. S. (2018). Orchestration of innovation networks in collaborative settings. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(6), 2562-2582. Web.

Nieth, L. (2019). Understanding the strategic ‘black hole’ in regional innovation coalitions: Reflections from the Twente region, eastern Netherlands. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 6(1), 203-216. Web.

Nyman, G. S. (2015). University-business-government collaboration: From institutes to platforms and ecosystems. Triple Helix 2(2). Web.

Porter, W. W., & Graham, C. R. (2016). Institutional drivers and barriers to faculty adoption of blended learning in higher education. British Journal of Educational Technology, 47(4), 748-762. Web.

Radinger-Peer, V. (2019). What influences universities’ regional engagement? A multi-stakeholder perspective applying a Q-methodological approach. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 6(1), 170-185. Web.

Rodríguez‐Pose, A., & Wilkie, C. (2019). Innovating in less developed regions: What drives patenting in the lagging regions of Europe and North America. Growth and Change, 50(1), 4-37. Web.

Siddiqui, K. A., Al-Shaikh, M. E., Bajwa, I. A., & Al-Subaie, A. (2021). Identifying critical success factors for university business incubators in Saudi Arabia. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues, 8(3), 267-279. Web.

Swansea University. (n.d.a). About us. Web.

Swansea University. (n.d.b). Faculty of humanities and social sciences. Web.

Thomas, E., Faccin, K., & Asheim, B. T. (2021). Universities as orchestrators of the development of regional innovation ecosystems in emerging economies. Growth and Change, 52(2), 770-789. Web.

Thomas, E., & Pugh, R. (2020). From ‘entrepreneurial’ to ‘engaged’ universities: Social innovation for regional development in the Global South. Regional Studies, 54(12), 1631-1643. Web.

van Weele, M. A., van Rijnsoever, F. J., Groen, M., & Moors, E. H. M. (2020). Gimme shelter? Heterogeneous preferences for tangible and intangible resources when choosing an incubator. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 45, 984-1015. Web.

Wakkee, I., van der Sijde, P., Vaupell, C., & Ghuman, K. (2019). The university’s role in sustainable development: Activating entrepreneurial scholars as agents of change. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 141, 195-205. Web.

Yousefi, M., & Abdullah, A. G. K. (2019). The impact of organizational stressors on job performance among academic staff. International Journal of Instruction, 12(3), 561-576. Web.