Background

Since 1960, Japan, Britain and U.S.A were recognized as the leading countries in the global economy. However, due to the embracing of technology and lessening of trade barriers, there has been swift economic development in developing nations like China, Singapore, Malaysia, Hong Kong and Taiwan. Currently, these nations are competing fairly with the developed nations with regard to the world output, with prospect predictions depicting that the developing nations are going to dominate the global economy.

Decrease of trade barriers under the General Agreements on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) led to the liberated flow of goods, services and resources between nations. The WTO system was also put in place for argument resolution, enforcement of trade rules and control of levy on manufactured goods, services and agricultural products.

Whereas the lessening of trade barricade made globalization of market and production a hypothetical prospect, technological change made it a solid actuality. Some technological advances included: microprocessors and telecommunications, the World Web and internet, and transport technology. Major progress in connections and information processing decreased the cost of universal communication hence the cost of synchronizing and controlling global organizations.

This research was designed to evaluate current practices across China, Singapore and Malaysia with comparison to the United States and Britain. The results depict that the developing nations, and especially China, are likely to dominate the world output.

Introduction

Over the years, there has been a swing towards a more incorporated and interdependent world economy, also known as globalization. Many firms source commodities and services from diverse locations around the world in an attempt to obtain advantage of national disparity in the cost and value of factors of production which include: land, capital, labor and energy, thereby enabling them to race more effectively with there competitors (Hill 24).

As a result, several global institutions have appeared so as to administer, regulate and control the global market place by encouraging the establishment of international treaties to oversee the global business organization. Some examples of international institutions include the World Trade Organization (WTO), World Bank, International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the United Nations (UN).

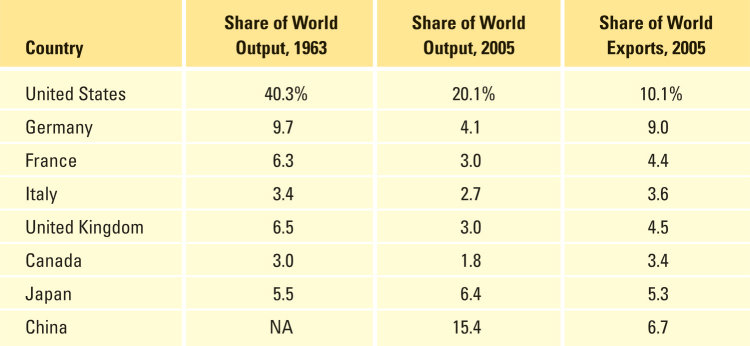

The two key factors that have encouraged globalization include: lessening trade barriers and technological change. Advancements in transportation technology have facilitated firms to better respond to global client demands. This has led to transformation in the global economy. For instance, in early 1960’s, U.S. subjugated the world economy accounting for almost 40.3% of the world industrialized output.

However, by 2005 the U.S. accounted for no more than 20.1%. This was as a product of the swift economic development that was experienced in other states like China, Malaysia and Singapore. Forecasts predict a swift rise in the share of globe output accounted for by developing nations like China, Hong Kong, Singapore and Malaysia and a turn down in developed nations like U.S. and Britain (Hill 32). This forms the rationale for the evaluation of exports and imports practices in these countries.

The paper starts with a definition of the key terms used followed by history of imports and exports, driving and impeding forces, case studies of China, Singapore and Malaysia, suggestions, future trends and finally, a conclusion.

Definition of Terms

- Globalization: the drift towards a more incorporated economic system.

- Globalization of markets: the verity that in various industries historically different and separate markets are integrating into one vast global market place in which the feelings and preferences of customers in different states are beginning to congregate upon some global standard (Rawski 43).

- Globalization of production: the propensity among several firms to font goods and services from diverse locations around the world in an effort to take advantage of nationwide discrepancies in the cost and factors of production which include labor, land, energy and capital, thus enabling them to compete more efficiently with their competitors.

- Exports: sale of goods and service to a foreign country.

- Import: Buying of goods and services from other countries.

- Internationaltrade: the sale of goods and services to customers in another state..

- Foreign direct investment: the supply of business practices and resources outside a firm’s dwelling nation.

- Stock: total collective value of overseas investments.

History of Imports and Exports

In the 1960’s, the U.S. was the globe’s leading industrial power accounting for almost 40.3 percent of universal production output (Kwan 20). In 2005, the U.S. accounted for not more than 20.1 percent. Swift economic development is now being experienced by states like China, Indonesia and Thailand.

An additional relative turn down in the U.S. share of globe output and universal exports appear likely. Forecasts envisage a swift rise in the share of globe output accounted for by emerging nations such as China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore and Malaysia and a turn down in the share by developed countries such as Britain, Japan and U.S. (shown in Table 1).

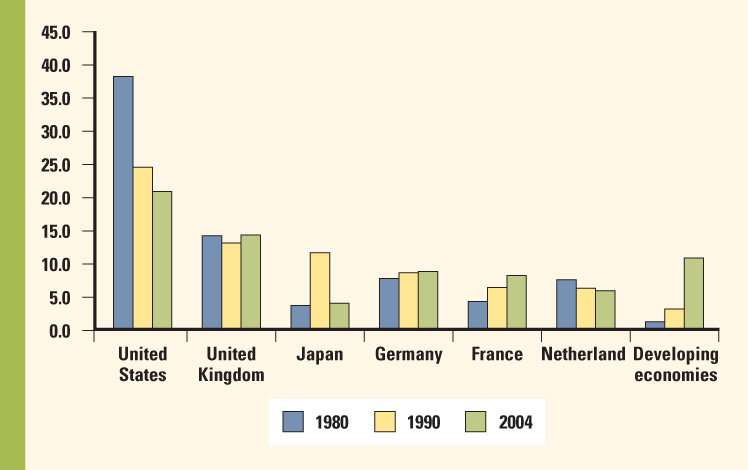

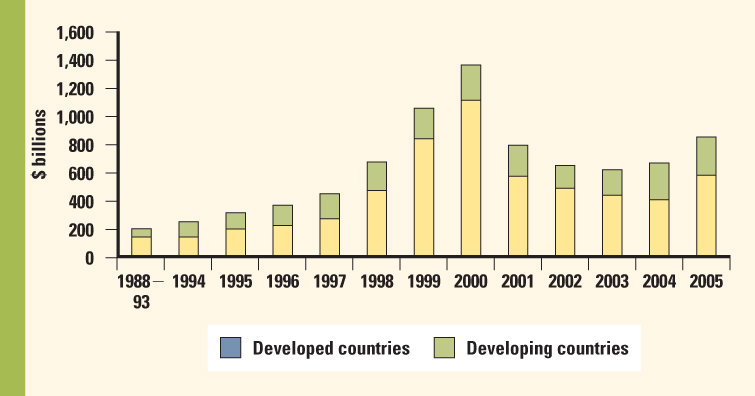

Changes have occurred in Foreign Direct Investments. Since 1960’s the distribution of world output created by counties has been gradually increasing. The stock made by rich industrial nations has been on a sound decline. There has been a continuous growth in cross-border streams of Foreign Direct Investment.

The stream of Foreign Direct Investment (quantity invested across state borders every year) has been aimed at developing states, particularly China ( Hill 32)). The stock of FDI by the globe’s six major important state sources is shown in Fig. 1 while the continued growth in cross-border streams of FDI and the surfacing of developing countries as important target for FDI is shown in Fig. 2

Driving and impeding forces

The two key macro factors that motivate the drift towards larger globalization include waning trade and investment barriers and technological transformation.

After the Second World War, the developed countries of the West initiated the process of eliminating barriers to the free stream of capital, goods and services between counties. As a result of establishment of the General Agreements on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), more than hundred countries negotiated more decreases in duty and made momentous progress on several non-tariff issues.

Through the establishment of the World Trade Organization (WTO), a forum for dispute ruling and enforcement of trade regulations came into being. The WTO also pushed the reduction of tariffs on agricultural products, manufactured goods and services.

The elimination of barriers to trade led to augmented international trade, globe output and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). The quantity of world trade and investments has increased since 1980’s.

Whereas the lessening of trade barriers made globalization of markets and manufacturing a notional possibility, technological transformation made it a tangible realism (Messerlin 87). Some technological advancement included: World Wide Web and Internet, transport technology, microprocessors and telecommunications.

Major transformations in communications and information processing lessened the cost of universal contact and therefore the cost of synchronizing and controlling an international organization. Web-based dealings have grown to $7 trillion in 2004 from virtually nil in 1996.

The most significant advancement in transport and technology consist of the development of commercial super freighters and jet air craft s, which significantly simplifies trans-shipment from to different forms of transport (World Trade Organization 5). All these technological advancements enable firms to well again respond to worldwide consumer demands. However, they have also formed a more aggressive and compound market environment.

Case Studies

China

Every year, China raises its imports and export due to various factors, one of them being an increase of China’s goods rivalry which has resulted to an extension of their shares in the global market (Kwan 245). To slacken trade in China, the Chinese administration reduces governmental obstacles to develop its attractiveness to the overseas companies through establishing bilateral and regional Free Trade Agreements (FTAs).

- China’s top exports include: electrical machinery and equipment, footwear, vehicles, excluding rail, optics and medical equipment, inorganic and organic chemicals, furniture, ships and boats, power generation equipment and iron.

- China’s top imports include: electrical equipment and machinery, power generation equipment, optics and medical equipment, ores, slag and ash, copper, iron and steel and mineral fuel and oil.

In the year 2010, the volumes of all export goods increased. For instance, electrical equipment and appliances had 388.8 volume which was a 29.1 percent change over 2009.In the same year, the volume also increased. For example, the volume of copper was 46.1 which was a 55.8 percent change comparing to the previous year.

China’s Trade Agreements

Companies take advantage of the FTAs to lessen the custom duties that are levied on commodities when they are imported into a nation. This has the advantage of lessening the landed cost, which improves profitability, market access and competitiveness. Commitment in China’s WTO rules and Working Party Report found rights and obligations enforceable in the course of WTO dispute settlement measures (Messerlin 34).

China and the USA have established key provisions involving protection against import surges, technology transfer requirements and counterbalance, as well as performance of state-owned and state-invested activities. These rules are of exceptional significance to USA workers and trade.

China has agreed to execute the TRIMs accord upon accession, eradicate and stop enforcing trade and foreign exchange harmonizing requirements, eradicate and stop enforcing local substance requirements, decline to enforce contracts commanding these requirements, and simply implement or enforce laws or other requirements relating to the shift of technology if they are in agreement with the WTO accords on guard of intellectual property rights and trade-associated investment procedures.

These stipulations will also help guard American firms against compulsory technology transfers, as China has also decided that, upon accession, it will not form investment approvals, import permit, or any other import approval procedure on performance requirements of any type.

Channel Distribution

Since 1979, the record of distribution in China has been loaded with infrastructure troubles and difficult legal issues, and several firms have been strained by those conditions to use highly creative techniques to bypass outdated and restraining regulations in order to distribute their goods.

To counter this, many alien firms have managed to put up countrywide distribution channels and are well placed to strive in a post-WTO China. Hitherto a good number of those same firms have to use a compound array of channels to achieve their distribution wants and find it hard to fuse to take benefit of economies of scale.

Nevertheless, the actuality of the marketplace has been the supreme driver of transformation in distribution. A close glance at what goods are accessible in the marketplace at present both on the coast and interior reveals enormous changes judge against five years ago. In spite of the infrastructure and logistics troubles, goods always appear to find their way to market.

Currently, overseas firms are not allowed to distribute products apart from those they make in China, or to run distribution networks, wholesaling channels or warehouses (Maddison 54). China also now regularly issues business permits which limit the capacity of American firms to carry out marketing, customer support, after-sales service, repair and maintenance. This is a severe baffler to goods and service exports.

However, China’s commitments deal with all these issues. They mirror a comprehensive undertaking on distribution including: retailing, wholesaling, sales away from a fixed position, transportation, and maintenance and repair. Thus, Americans are able to dispense imported products as well as those prepared in China, offering a major opportunity to enlarge USA exports of goods.

China is coming up with ways of discarding all boundaries on distribution services for nearly all products. Chinese dedication in services supporting distribution include hire and leasing, freight forwarding, air courier, advertising, storage and warehousing, technical analysis and testing and casing services.

It is anticipated that then, USA service traders will be able to found 100 per cent wholly owned auxiliaries. It is worth noting that the U.S. has a more constructive meaning of chain store than that which presently exists in Chinese law.

Tax Incentives

Incentive rule took full form in 1991 with the ratification of the Income Tax Law of the People’s Republic of China enterprises with Foreign Investment and Foreign Enterprises (FEITL). Many of the common forms of tax motivation can be found in this law and its execution rules. Some of the most important includes: tax holidays and reduced rates for manufacture-oriented ventures and accelerated depreciation refunds for reinvesting profits (Hills 24).

Following the execution of the Enterprise Income Tax Law on 1 January 2008 (the 2008 EIT Law), the structure of China’s tax incentive regimes altered radically. Previously, alien investors took enjoyment in tax incentives that were not accessible to home investors. However Under the 2008 EIT Law, tax incentives were applied to domestic enterprises, tough their range was much reduced.

Singapore

Singapore is rated as the fourteenth largest exporter and the fifteenth biggest importer in the globe (Banerjee 16). For a long time, international trade has powerfully impacted the economy. Singapore has the maximum trade to GDP share in the globe at 407.9 percent. Due to its geographical location and urbanized port facilities, 47 percent of exports are made up of re-exports.

As a sturdy backer of free trade, Singapore has comparatively few trade barriers. Trade cohorts with Most Favored Nation (MFN) have no tariff rates applied to their goods apart from six lines for hard beverages. There are though some imports limitations originate mainly on health, ecological, and public safety concerns. Rice import also requires import permit in order to guarantee food security and price steadiness

Trade Agreements

Laws in Singapore have been formulated to mirror dedications made under a variety of FTAs (Baneerjie 25). For example, the customs law in Singapore has been formulated to confer better tariff treatment and other treatment as agreed under the FTAs.

Apart from the governmental changes, Singapore now also promises, through treaty commitment, such action for imported goods, investments and services as are in the commitment made to its FTA associates. Such treatment includes state treatment and admission to investor arbitration.

Apart from alterations to mirror preference in the importation of merchandise, customs law has also been adjusted to provide procedures for subject of preferential certificates of source for relevant producers or exporters of goods from Singapore to FTA associate countries.

For example, subsequent to FTA with the U.S. Singapore import/export laws now allow the import of chewing gum with advantageous value and the export of textile and clothing goods of the WTO Agreement on clothing and textiles is now synchronized under Singapore export/import law. The law states that where any part of the produce of such goods is conceded or secured by any individual in Singapore, for such merchandise to be exported from USA TO Singapore, such an individual must be registered.

Singapore has undertaken dedication through a number of FTA agreements to guarantee a certain level of intelligibility with respect to its decrees and legal processes. The commitments bode well for foreign businesses as they advance strengthen Singapore’s legal structure. Warning and consultation requirements are included in some cases to make sure that interested persons can offer input and feedback on anticipated changes to law and rule.

Overseas investors and investments roofed under the various FTAs take pleasure in certain assurances in relative to expropriation of goods (Maddison 56). The FTAs contain pledges on the conditions under which such feat may take place as well as on the reimbursement that must be given must such action happen.

In some instances, side letters complementary to the FTAs provide further knowledge about the parties’ position on such deed. These FTA commitments are significant in giving shareholders and investments from FTA associate countries guard beyond that existing under WTO agreements and common Singapore business law.

Singapore is a party to the WTO’s Government Procurement Agreement. Due to FTA commitments, Singapore currently offers a more striking procurement setting to its FTA partners. The enhancements include those relating to entrance values of procurement agreements.

To additionally promote trade, several mutual recognition agreements (MRAs) on compliance assessment for several goods have been signed by Singapore and her trade partners including Japan, United States and Australia. These agreements deal with goods such as pharmaceuticals, food and horticultural products, electrical and electronic goods and telecommunications equipment.

Through Singapore’s FTAs, country-country dispute resolution processes have been formed to provide partner countries and Singapore with added avenues for solving their disputes. The dispute settlement rules differ from FTA to FTA in their range and operation. They usually offer for consultation procedures as well as international mediation.

Singapore’s major imports partners are: China, Malaysia, Indonesia, South Korea and Japan. Singapore’s sum trade in 2010 added to $661.58 billion, 20.7% more from 2009. In 2010, Singapore’s imports summed to $310.39 billion while exports totaled $351.18 billion. Singapore’s major import source country was Malaysia, as well as its chief export market, engrossing 11.9% of Singapore’s exports, seconded by Hong Kong with 11.7%.

Other main export markets included the U. S. with 6.4%, Indonesia with 9.4% and China with 10.3%. Singapore was ranked the 13th-largest trading partner of the U.S. in 2010. Re-exports were responsible for 48.1% of Singapore’s sum sales to other states in 2010.

Singapore’s chief exports are, food and beverages, chemicals, petroleum products pharmaceuticals, electronic components, transport equipment and telecommunication apparatus. Singapore’s key imports are petroleum products, aircraft, electronic components, crude oil, consumer electronics, chemicals, industrial machinery and equipment, motor vehicles, food and beverages, iron and steel and electricity generators.

Malaysia

Malaysia, part of South East Asia has been a trade center for centuries (Cottier 67). Since the commencement of history, Malacca has been a fundamental region business center for Indian, Arab, Chinese and Malay merchants for trade of valuable merchandise (Das 145). At present, Malaysia holds healthy trade affairs with a number of states, particularly the US.

The nation is associated with trade groups, such as ASEAN, WTO and APEC. The ASEAN Free Trade Area that was founded for trade support among ASEAN associates also has Malaysia as its origin member. Malaysia also has Free Trade Agreements with nations like Pakistan, China, Japan and New Zealand. Most of Malaysian exports to U.S. are computer accessories, computers & telecommunications equipment (55%) while Malaysian imports from America (43%) are semiconductors.

The U.S. consumes almost 19% of Malaysian exports. Other chief customers for Malaysian exports include Japan (8.9%), China (7.2%), Singapore (15.4%), Hong Kong (4.9%) and Thailand (5.3%).Principal Malaysian exports are petroleum and liquefied natural gas, palm oil, electronic equipment, wood and wood products and rubber and textiles.

Japanese products account for 13.3% of imports into Malaysia, followed closely by America at 12.6%, China at 12.2% and Singapore at 11.7%. Thailand (5.5%), Taiwan (5.5%), South Korea (5.4%) and Germany (4.4%) furnish considerable import amounts to the southeastern Asian nation. Principal imports from Malaysia include electronics, machinery, petroleum products, plastics, vehicles, chemicals, plus iron and steel products.

In the year 2007, Malaysia exported a projected US$181.2 billion worth of merchandise onto the global trade marketplace. Malaysian imports summed up roughly $145.7 billion, leading to Malaysia’s $35.5-billionn in general trade excess last year.

Malaysian Trade with the U.S.

A closer glance at Malaysia’s trade figures with the United States indicate that in 2007, Malaysia enjoyed a US$21.1 billion trade surplus with its American trade partner. The latest surplus gauge is 45.3% higher than the Malaysia to US surplus in 2003 but symbolizes a 12% reduction from the 2006’s $24 billion surplus.

Exports from Malaysia to U.S. In 2007, Malaysia exported US$32.8 billion value of goods to the United States in 2007, indicating a 10.2% decline from 2006 and up 28.9% in four years. In total, Malaysia’s top ten export merchandise categories experienced declined sales to the U.S. in 2007, losing 12.5% from 2006. This compares with an 8.5% increase for the top ten export s to the U.S. from 2005 to 2006.

The fastest growing Malaysian exports to U.S. include: food oils and oil seeds, industrial organic chemicals, fuel oil, other automotive parts and accessories and business machinery other than computers. The fastest decreasing Malaysian exports to U.S. include: crude oil, semi-finished iron and steel mill products, telecommunications equipment, stereo equipment and video equipment.

In the year 2007, Malaysian imports fell by 6.9% TO $11.7 billon, an increase by 7% since 2003.

Why Companies Use these Countries

Many companies use these counties because they have a level stage field for all with no overseas ownership boundaries, have low, easy, and conventional tax regime, capital gains, shares, and sales, and have a rule of decree that allows free association of talent, capital and groups (Akamitsu 43).

Future Trends

In future, it is expected that the three countries, China, Malaysia, and Singapore will experience rapid economic growth while the developed nations like Britain and the U.S. will experience a decline in the global economy.

Suggestions

Noting that the actions of most governments bound economic development in many countries, it is important for all governments to reduce trade barriers and adopt the FTAs.

Among the benefits of FTA’s include: accord and improve long term market entry prospect for products and services, give access to less expensive imports from the FTA partner states, which is seen as inputs for the nation’s exports; boost a nation’s position as a striking target for foreign direct investment, encourage capability building through economic and technical collaboration tasks, develop the effectiveness and competitiveness of a state’s industries, through better rivalry and economies of scale, and aid trade through founding of mutual recognition accords.

FTAs can also be used by companies to enlarge and infiltrate foreign markets. With easier market entrance companies can embark on joint business enterprise or acquisition into the foreign markets. The removal of import duties on bargained products serve as an aperture for a country’s goods to be established into the foreign market, apart from mounting current market share. Industrialized companies should take benefit of duty removal or substantial lessening, especially in countries which have the benefit of preferential treatment.

Firms must be conscious that while the new integrated global economy presents novel chances, it could also outcome in political and economic commotion that may throw plans into dismay.

Conclusions

As a result of trade liberalization and technological advancements, there has been an increase in the exports and imports among developing nations like China, Malaysia and Indonesia. Trade barriers are reduced through the establishment of FTAs. For developed countries which have continued to ignore the FTAs, it is predicted that their world output will decline. Free trade enables countries to concentrate in the production of those merchandise and services that they can produce most proficiently, while importing those merchandise and services that they can not generate competently.

FTAs also enable industries to font inputs at more viable prices. Bilateral FTAs enable developing countries to expand their services and goods into other countries through partnerships with projects from FTA members. FTAs can offer trade supporting actions for industries to enlarge trade, as well as capacity building to advance and increase their competitiveness.

Technological advancements and tax incentives have also contributed largely to the growth of exports/imports. It is predicted that in future, the developing nations, particularly China will take a lead in the world output, hence the global economy.

China’s top exports include electrical machinery and equipment, footwear, vehicles, excluding rail, optics and medical equipment, inorganic and organic chemicals, furniture, ships and boats, power generation equipment and iron. Its top imports are electrical equipment and machinery, power generation equipment, optics and medical equipment, ores, slag and ash, copper, iron and steel and mineral fuel and oil.

Singapore’s chief exports are, food and beverages, chemicals, petroleum products pharmaceuticals, electronic components, transport equipment and telecommunication apparatus. Singapore’s key imports are petroleum products, aircraft, electronic components, crude oil, consumer electronics, chemicals, industrial machinery and equipment, motor vehicles, food and beverages, iron and steel and electricity generators.

Singapore’s major imports partners are China, Malaysia, Indonesia, South Korea, and Japan. Singapore’s sum trade in 2010 added to $661.58 billion, 20.7% more from 2009. In 2010, Singapore’s imports summed to $310.39 billion while exports totaled $351.18 billion.

The fastest growing Malaysian exports to U.S. include food oils and oil seeds, industrial organic chemicals, fuel oil, other automotive parts and accessories and business machinery other than computers. The fastest decreasing Malaysian exports to U.S. include crude oil, semi-finished iron and steel mill products, telecommunications equipment, stereo equipment and video equipment.

A closer glance at Malaysia’s trade figures with the United States indicate that in 2007, Malaysia enjoyed a US$21.1 billion trade surplus with its American trade partner. The latest surplus gauge is 45.3% higher than the Malaysia to US surplus in 2003 but symbolizes a 12% reduction from the 2006’s $24 billion surplus.

In developing states, the figure of mini-multinational companies is swiftly increasing. The economic growth of China presents gigantic opportunities and threats in spite of its continued communist’s control.

References

Akamatsu, Kark. A Theory of Unbalanced Growth in the World Economy. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Banerjee, Peter. Beyond the Transition Phase of World Trade Organization: A Singapore Perspective on Emerging Issues. New Delhi, Academic Foundations, 2009.

Cottier, Margaret. International Trade and Free Trade Agreement in Malaysia. London: Sage, 2009.

Das, Dilip. “Liberalization Efforts in Malaysia and Accession to the World Trade Organization.”The Journal of World Investment, 2008, 2: 761-789.

Hill, Charles. Global Business Today. 7th ed. New York: University of Washington, 2010.

Kwan, Chile. The Rise of China and Asia’s Flying Geese Pattern of Economic Development. Tokyo: Nomura Research Institute, 2009.

Maddison, Albert. The World Economy: A Millennial Perspective. Paris: OECD Development Center, 2008.

Messerlin, Patrick. China in the WTO: Antidumping and Safeguards. Geneva: World Trade Organization, 2008.

Rawski, Thomas. “What is Happening to China’s GDP Statistics?” China Economic Review, 2009, 12: 374-54.

World Trade Organization. International Trade Statistics 2010. Geneva: World Trade Organization, 2010.