Introduction

Pricing of products and services is of fundamental importance in the four elements of marketing mix that generates profit for business enterprises. According to Boone and Kurtz (2011), the factors that influence the price of commodities and services can be categorized as external and internal.

Pricing thus, is more than just simple calculations of the cost of production and setting up a markup (Giddens, Parcell & Brees 2005). Consequently, pricing policy becomes a major component of enterprise marketing plan, which is part of the whole business plan (Boone & Kurtz 2011). Moreover, pricing policy ultimately affects the other marketing mix elements of the product which in turn, impact on how the product is viewed by consumers and purchase decisions (Giddens, Parcell & Brees 2005).

Target market segment

The target segment is a part of consumers that can be optimally served by the company’s projected and existing capacities at a profit. The introduction of more efficient technologies has enabled construction of lighter, less expensive, and more powerful radio and aircraft systems (Doyle 2002).

As a result, there has been a global rise in the hobby of flying RC airplanes and the application of such airplanes in the military and scientific research organizations. The target market for the new RC airplane will be individual users, research stations, governments, and military units. However, it is worth noting that each of the target users mentioned is unique and requires different marketing and pricing strategies that can be adjusted in accordance to prevailing market conditions (Kotler 1997).

Channel of distribution

The sole objective of every business enterprise is to make profit by selling their commodities and services to consumers or ultimate users. In order for the producer of the commodities to achieve this objective, they must ensure that the goods they produce reach the consumer. The goods must follow a defined distribution network to reach the consumers via what is commonly referred to as trade channel or distribution channel (Kotler 1997).

In fact, the trade channel acts as the link between the producer and the consumers; therefore, any channel of distribution comprises the producer, middlemen, and final buyers (Anderson & James 1990).

Selling the new RC airplanes will be done using the indirect method distribution channel; however, caution will be taken to ensure that middlemen are minimized. Minimizing the middlemen (Kotler 2003) is essential in ensuring profit maximization and that consumers are not overcharged since every middleman charges extra profit or commission for the goods they sell.

In fact, according to Anderson and James (1990), goods that are produced in large quantity cannot reach the final users or consumers at the right time and place without the input of middlemen. Consequently, they will be sold via two middlemen as depicted in figure 1.1 below.

Fig: 1.1: Distribution Channel for the new RC airplanes

Source: (Anderson & James 1990)

Prior research to adoption of pricing policy

According to Aaker (1999), good policies are vital for the attainment of progress in both economic and social spheres. Price policy formulation; thus, is central to success of any business enterprise and more often the quality of price policies formed is depended on the capacity of the marketing team in the business and the strategies employed by the team (Frank 1998; Boone & Kurtz 2011).

Before making any price policies, it is important for the firm to carry out research on the factors affecting pricing; both internal and external. Furthermore, the pricing policy should compare all the available pricing options and result in an acceptable price level range for the product (Uva 2001). Anderson and James (1990), note that performing prior research to determine most appropriate pricing strategies is important as the knowledge acquired can be used in assigning the best price markups for the products.

To achieve an acceptable pricing policy, it is important for the marketing team to carry out prior research in the following areas;

- on the mix of products they intend to offer in the market, this is important because it limits or broadens the pricing strategies options available for the business to exploit;

- market research to be able to determine the target market and the best possible pricing goals and strategies for the targeted market demographics;

- the best method of distribution or channel of distributions of products ultimately impacts on the pricing strategies, for example, direct sales grants the producer more control over the product in terms of pricing, or displays as opposed to wholesale;

- research should be done on the approximate life cycle of each product since the life cycle of the product determines the quantity to produce at a particular time. For example, goods with estimated short life cycles require that they are produced in massive quantities to be able to generate bigger profit margins, while those with estimated long life cycles gives the producer time to attain their pricing objectives;

- policies such as government regulatory policies that may impose price regulations on your product by limiting the maximum prices that can be charged for the product;

- finally, the company ought to carry out prior research on the anticipated product demand. For example, projected high demands means that the consumers will highly unlikely be concerned with price of the product thus the producer has more flexibility in choosing an appropriate pricing strategy (Uva 2001; NetMBA 2005).

Pricing objective

The pricing objective to be adopted by the company for the new RC airplanes will be quantity maximization since the company’s main mission is to become a leader in terms of market share amongst companies producing RC aircrafts. Consequently, the pricing objective of the company seeks to maximize the number of the new models of RC airplanes sold (Giddens, Parcell & Brees 2005).

Pricing strategies

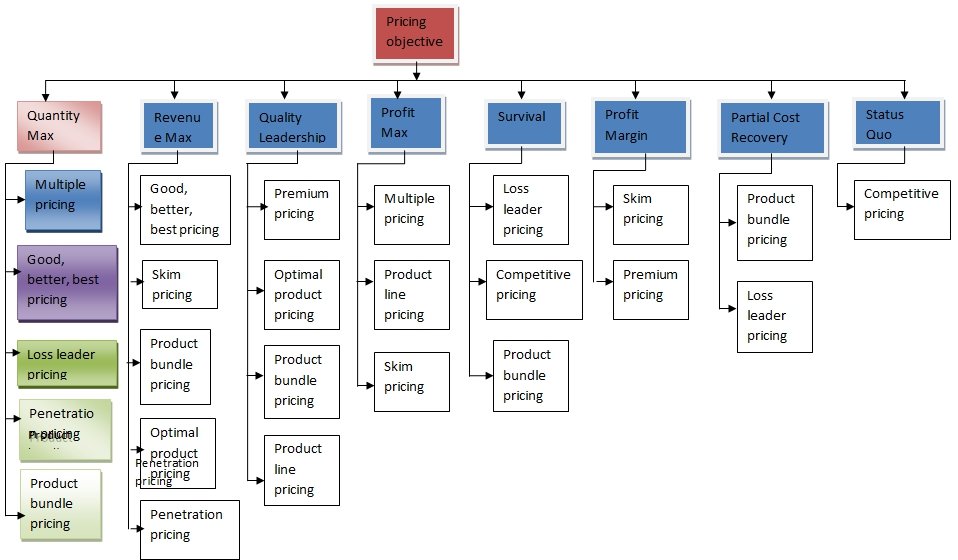

According to Kotler (2003), several pricing strategies exist for companies to choose from, however, some of these pricing strategies only work well with certain pricing objectives. Uva (2001) advises that a careful selection ought to be done by business managers when choosing a pricing objective as the choice of appropriate pricing strategies depends on the selected pricing objective.

Moreover, each pricing objective works well with a particular set of pricing strategies (Figure 2.2). Finally, it has been noted (Doyle 2000) that different pricing strategies can be successfully applied at different times to fit the changing market strategies, product life cycles, and market conditions.

Figure 2.2: Pricing objective and strategies

From figure 2.2 above, it can be noted that owing to the pricing objective of the company; quantity maximization, the best marketing strategies would be as follows: (1)Multiple pricing; (2) Good, better, best pricing; (3) Loss leader pricing; (4) penetration pricing; and (5) product bundle pricing (Uva 2001; Doyle 2002).

Multiple pricing: aims at luring customers to make large purchases by offering slight discounts to customers who buy goods in large quantities. The prices of single items are slightly higher to those that purchased in bulk (Boone & Kurtz 2011). For example, buying one new RC airplane will cost the customer approximately $ 85; the customer will be required to pay $ 165 for two RC airplanes. As a result, the customers will feel that they are getting discount for buying two items since $ 82.5 (165÷2) is $ 2.5 less than $ 85.

However, $ 82.5 is the price that the company would be charging for each new RC airplane if the company was not employing the multiple pricing strategies. The strategy will be able to generate more profit for the company by increasing the quantity of items sold, as well as through increasing prices for customers who purchase one item. Practically, the strategy penalizes the customer for purchasing one item since the price is typically set higher than it will cost; that is at $ 85 instead of $ 82.5.

Good, better, best pricing: this is a pricing strategy in which the price of the same item increases with slight changes that are made to the product, for example, changes in packaging. The price can be offered in a series of three formats with the price of each series rising above the price of the previous series (Doyle 2002).

The goods that are priced at ‘better” price and those that are priced at “best” price require more attention from the producer than those with“good” price; however, the higher prices charged for them are worth the extra effort (Achrol 1997; Day & Liam 1988).

For example, the new RC can be categorized into those that are very heavy, slow, and noisy as being “good” price, while those that are less heavy, fast, and produce relatively low noise as “better” price and those that are light, faster, and have noise minimization capabilities as being priced at “best” prices.

Loss leader pricing: in this strategy, the customers are enticed into visiting the shop that deals with different product or parts by reducing the price of one item. This is done with the hope that when customers visit the shop to make purchase of the cheaper item they may also buy other items (Alderson 1937).

For example, in applying this strategy to the pricing of the new RC airplanes, the company will use other accessories such as the RC airplane battery as the loss leader product, thus customers who come to buy the RC airplane batteries may end up buying other accessories or even purchase a new model of the RC airplane.

Penetration pricing: this is a strategy that is employed by business enterprises that want to break into a new market or segment of the market that is not previously served by the business. The main objective of the penetration pricing strategy is to attract and increase the market share of the product (Day & Liam 1988).

Therefore, applying the penetration pricing strategy requires that the business reduces the prices to a certain minimum in order to attract customers; however, this price must be increased once the management is satisfied that the objective has been attained as this strategy initially reduces profit margins significantly (Urbany 2001).

For example, if the market research indicated that the competitors sold their RC aircrafts for $ 83 to $ 99, then the company will have to sell the new RC airplane models for about $ 80 in order to attract customers since there are already several other RC airplane sellers in the market and the company is new.

This will be done for six months after which there will be a price review upwards as the price of $ 80 covers the production cost but it is the lowest of the market range. This pricing strategy achieves the objective of the quantity maximization by increasing number of items sold at low prices. At the same, the strategy can help in revenue maximization that results from the large numbers of purchases made (Whitefield, 1994).

Product bundle pricing: this pricing strategy is applied when the producer wants to get rid of overstock or sell complementary products. The products are bundled together and the customer who buys the new item can get an older or complimentary good for less (Day & Liam 1988; Doyle 2002).

In respect to the new RC airplane models, the company may decide to sell the older versions or accessories that are compatible with the new models in bundles at lower prices. Product bundling will help the company achieve its objective by making it possible to sell items that might have not been sold.

Procedure for price calculation

In calculating the unit cost of the new RC airplane models, the company will apply the Conjoint Analysis (Curry 1996), which is a marketing research tool that is used to determine attributes the new product and how the new features affect the price of the new product.

The choice to use conjoint analysis is supported by the fact that it is flexible and less expensive to carry out than concept testing (Trout 1998; Nagle & Holden 2001; Rhim & Cooper 2005). Suppose the company intended to produce sets of new RC airplanes, from the users’ perspective and experience, the new sets will be affected by some important product features, for example, speed, average plane life, and price.

Table 1: Attributes of new RC airplane

From table 1, it clear that the markets “ideal” RC airplane is the one that has a speed of 80Km/hr, an average life of 60 falls, and is less expensive costing $ 82.5. However, from a manufacturing perspective the “ideal” new RC airplane is that which has a speed of 60Km/hr, has shorter life cycle of 35 falls, and cost more at $ 90 assuming that it cost less to manufacture RC airplanes that are slow and have shorter life cycles.

Ranking the features conjointly between two buyers

Table 2: Buyer 1

Table 3: Buyer 2

From table 2 and 3 the buyers tend to agree on the least preferred feature of the plane, but, buyer one tends to tradeoff average speed to ball life while buyer two makes an opposite tradeoff. Next is to figure out a set of values that when summed up produces buyer one’s rank as shown in table 3.

Table 3: Set of values that produce buyer’s preferences

Suppose table 4 represents the tradeoffs buyer one buyer one is willing to make between price and average airplane life:

Table 4a

Table 4b

From the analysis the company then ends up with a set of complete values known as utilities that capture buyer 1’s tradeoffs a shown in table five below.

Table 5: Buyer 1 tradeoffs

The company will use the table above in calculating the price of the RC airplane to produce as follows: suppose the company intends to produce two models of RC airplane as show in table 6.

Table 6

Then, the values for buyer one in table 5 when summed up provides the estimate of the buyer’s preferences as shown below in table 7.

Table 7

From table 7, it can be concluded that the customer is likely to prefer long life RC airplane over the faster model because it has the highest amount of utility. The company should produce life RC airplanes and sell them at about $ 90 per item.

Due to multitude and complexity of factors involved in determining the price of products, assembling relevant information on the market conditions will determine the long term price changes. However, the short term price policies are tactical in nature as they endeavor to realize short term business objectives, and will be employed in relation to the goal they are intended to achieve.

List of References

Aaker, D A 1999, Managing brand equity: capitalizing on the value of a brand name, The Free Press, New York.

Achrol, RS 1997, “Changes in the theory of inter-organizational relations in marketing: toward a network paradigm”, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, vol. 25 no. 1, pp. 56-71.

Alderson, W 1937, “A Marketing view of competition”, Journal of Marketing, vol.1, pp.189-190

Anderson, J C & James, A N 1990, “A Model of distributor firm and manufacturer firm working partnerships”, Journal of Marketing, vol.54, pp. 42-58.

Boone, LE & Kurtz DL 2011, Contemporary marketing, Cengage Learning, Belmont CA

Curry J 1996, Understanding conjoint analysis in 15 minutes: Quirk’s Marketing Research Review, Sawtooth Technologies, Inc.

Day, G S & Liam F 1988, “Valuing market strategies”, Journal of Marketing, vol.2, pp. 45-57

Doyle, P 2000, Value based marketing: marketing strategies for corporate growth and shareholder value, Wiley, Chichester.

Doyle, P 2002, Marketing management strategy, Prentice Hall, Harlow

Frank, G 1998, Cost of production versus cost of production, University of Wisconsin Press, Madison.

Giddens, NJ, Parcell, & Brees M 2005, Selecting an appropriate pricing strategy, viewed on <https://www.extension.iastate.edu/agdm/>

Kotler, P 1997, Marketing management: analysis, planning, implementation and control, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Kotler, P 2003, Marketing management, Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ

Nagle, T & Holden, R 2001, The strategy and tactics of pricing, Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ.

NetMBA 2005, Pricing strategy, viewed on <http://www.netmba.com/marketing/pricing/>

Rhim, H & Cooper, LG 2005, “Assessing potential threats to incumbent brands: new product positioning under price competition in a multi segmented markets,” International Journal of Research in Marketing, vol. 22, no. 2, pp.159-182.

Trout, J 1998, “Prices: simple guidelines to get them right,” Journal of Business Strategy, vol. 22, pp. 13-16.

Urbany, JE 2001, “Are your prices too low?” Harvard Business Review, vol. 79, no. 9, pp. 26-28.

Uva, W L 2001, Smart pricing strategies, Department of Applied Economics and Management, Cornell University, Ithaca.

Whitefield, J 1994, Conflicts in construction: Avoiding, managing, resolving, MacMillan, New York.