Purpose

Identifying microbes is the process of determining the species or type of a microorganism based on the study of cultural, morphological, biochemical, serological, and pathogenic properties. The cultural properties of microorganisms are determined by inoculating them on liquid, semi-liquid and solid media (Thomas & Segata, 2019). Determination of these microbes is an essential task for any researcher for several reasons, primarily due to microbiological problems. First, pathogen identification is necessary for choosing an antibiotic therapy regimen to treat purulent infections and sepsis. Secondly, this process allows for optimizing activities in monitoring biological threats. Finally, comparative analysis brings the subject area closer to answering many questions of applied importance in medicine, surveying, and other sciences related to human activity, often using advanced information technology methods (Baldrian, 2019; Das & Dash, 2018, Harrington et al., 2021, Modha, 2022). In this laboratory work, a series of tests determine the nature of an unknown bacterium, number 9.

Materials and Methods

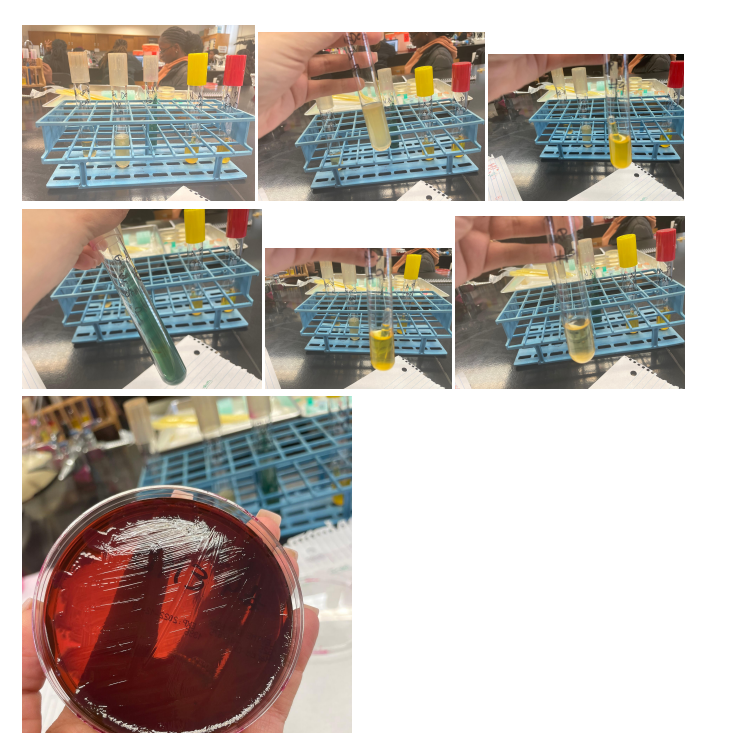

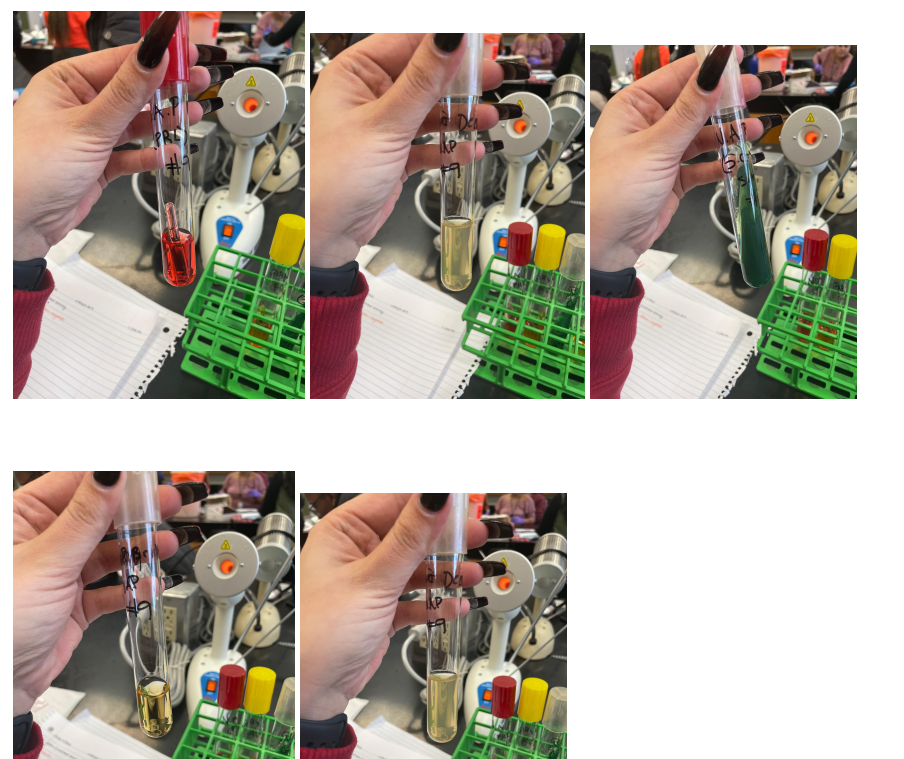

First, in this work, the Gram test was applied – a staining method that allows us to divide this group of prokaryotic microorganisms into gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria. After determining the group of bacteria, a series of tests specific to this classification is applied. In this work, the Gram test showed a Gram-negative bacterium; hence the following tests were used for glucose and lactose, Indole, MR, VP, Citrate, and H2S tests.

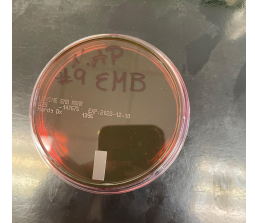

Fermentation of lactose, detected by the traditional method, occurs with the participation of two enzymes: permease, which ensures the transfer of the lactose molecule into the bacterial cell, and b-galactosidase, which splits lactose into galactose and glucose. Non-lactose fermenting bacteria lack both enzymes (Talaiekhozani, 2021). Glucose, lactose, and EMB tests are used to identify bacteria with a latent ability to ferment lactose, a hallmark of members of the Enterobacteriaceae family.

Indole is one of the breakdown products of tryptophan during bacterial metabolism. In media containing sufficient tryptophan, indole can be detected by its ability to react with certain aldehydes to form a stainable compound. It can be done using the drop test, a rapid method that is particularly useful for the preliminary identification of E. coli (Talaiekhozani, 2021). An alternative method for determining indole is the conventional tube test, which requires overnight incubation of crops. Kovacs reagents are used as indicators.

The MR test determines the concentration of ions (pH) in the medium of glucose-fermenting microorganisms. All members of the Enterobacteriaceae family convert glucose to pyruvic acid via the Embden-Meyerhoff metabolic pathway. The methyl red indicator used in this test turns the medium red at pH<5.0 and yellow at pH>5.8 (Talaiekhozani, 2021). Most enterobacteria use one end-of-life glucose pathway, which allows them to be differentiated using this test.

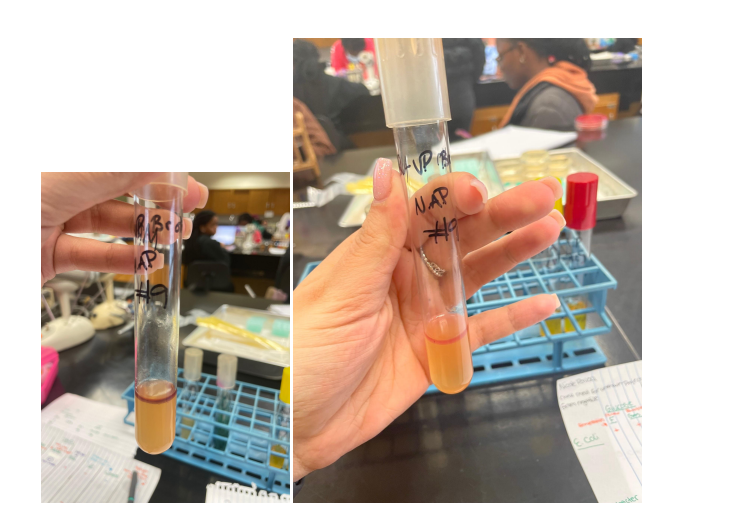

The VP test detects acetoin (acetyl-methylcarbinol), an intermediate product in the conversion of pyruvic acid, which is formed during the breakdown of glucose via the butylene glycol pathway (Talaiekhozani, 2021). In the presence of oxygen and KOH, acetoin is oxidized to diacetyl, which forms a red compound. The sensitivity of the test increases with the addition of α-naphthol prior to the addition of KOH.

Some microorganisms can utilize citrate as the sole carbon source. Since ammonium salts serve as a source of nitrogen in a medium with citrate, the growth of bacteria is accompanied by alkalization of the medium (pH > 7.6) with a change in its color in the presence of an indicator. This trait is used in differentiating members of the family Enterobacteriaceae and other Gram(-) rods: this explains the use of the citrate test (Talaiekhozani, 2021). Moreover, some organisms are capable of the enzymatic release of sulfur from sulfur-containing amino acids or inorganic compounds. Formed by interaction with hydrogen, it can react with some salts of iron and lead, indicators of sulfur compounds, with the formation of insoluble precipitates of iron sulfide or zinc sulfide, painted black.

Table of Results

Table 1. Results

Discussion of Results

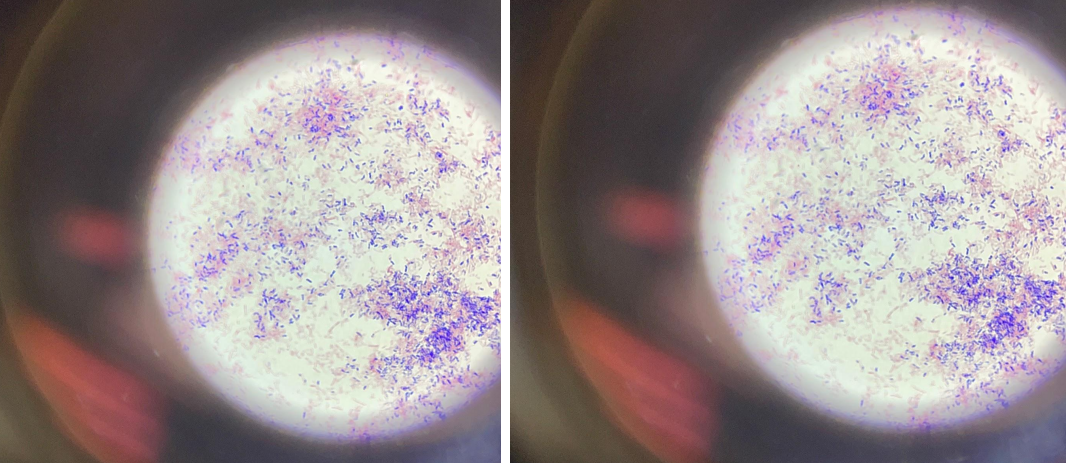

Gram-negative bacteria are covered on the outside with a single layer of peptidoglycan associated with the cytoplasmic membrane utilizing a lipoprotein; the outer membrane consists of lipopolysaccharides, phospholipids, and proteins. Due to the higher lipid content, the cell walls of gram-negative bacteria have increased permeability, and when decolorized with alcohol, the primary violet complex of the dye is easily removed through the pores of the cell wall, after which the bacteria acquire an additional color: bright crimson. The purple color in Figure 1 is due to the separation of liquid streams after repeated immersion of the drug in alcohol. After exposure to the dye, the bacteria acquired a crimson color.

The number of bacteria narrowed to three, and further tests showed that the desired bacterium is exactly E. coli for several reasons. Firstly, due to the breakdown of tryptophan, indole is released, which, as a result of reactions with aldehydes, gives a red color, which makes it possible to identify E. Coli over other candidates preliminarily. Secondly, the apparent alkalinization of the medium in the citrate test due to bacterial growth leads to a green coloration, which indicates a negative result of the test and identification of E. Coli. Otherwise, the medium did not change color during glucose fermentation in the H2S test, indicating a bacterium of the Enterobacteriaceae family. Appendix A contains photographs of the results of these tests.

Significance

Escherichia coli are stable in the environment, persist in soil, water, and feces for a long time, and tolerate drying well. Bacteria can multiply in food products, especially in milk, but they quickly die when boiled and exposed to disinfectants: bleach or, for example, formalin. Wide Escherichia coli varieties, including more than 100 pathogenic types, are grouped into four classes: enteropathogenic, enterotoxigenic, enteroinvasive, and enterohemorrhagic. There are no morphological differences between pathogenic and non-pathogenic Escherichia. The number of Escherichia coli, among other representatives of the intestinal microflora, does not exceed 1%, but they play a critical role in the functioning of the gastrointestinal tract (Denamur et al., 2021). Deviations from average values are a sign of dysbacteriosis. For bacterial overgrowth, bacteriophages or drug therapy with probiotics are used.

Pathogenicity, or the potential ability of bacteria to cause an infectious disease, refers to a genetic trait that arose during the evolution of microorganisms. E. coli refers to opportunistic microorganisms that, under normal living conditions in animals or humans, do not cause an infectious process (Denamur et al., 2021). The pathogenic genotype of opportunistic bacteria can be realized only in animals with imperfect immunity or incomplete physiological development, as well as in the weakening of their immune system and natural resistance, which prevents the invasion of these bacteria or the manifestation of the toxic effect of their products. For physiologically complete organisms, E. coli, as, indeed, for other members of the Enterobacteriaceae family with an opportunistic genotype, remain non-pathogenic.

Depending on the pathogenicity factors and the mechanism of their pathogenetic effect on the macroorganism, E. coli, pathogenic for animals and humans, can be divided into two groups. The first group consists of invasive strains that cause diarrhea syndrome – enterocolitis. The second includes non-invasive forms characterized by two features: they multiply and colonize in the area of the small intestine; produce one or more enterotoxins (Denamur et al., 2021). In strains of the second group, the toxin responsible for the development of the enterotoxic effect has nothing to do with the first stage of the interaction of the microbe with the cells of the intestinal epithelium. This stage is carried out by adhesins located on the cell surface. E. coli adhesins play the role of a mediator in the attachment of microbial cells to epithelial microvilli, and therefore are considered as colonization factors. With the help of adhesins, the process of recognition by enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli of the corresponding tissue in the small intestine, which is sensitive to the action of the toxin produced by this pathogen, is carried out (Denamur et al., 2021). During colonization of the mucous membrane, enteropathogenic Escherichia coli do not penetrate into the epithelial tissue itself and are found over the entire surface of the epithelium villi from top to bottom and even on the marginal bristles. They are not found in crypts. Non-enterotoxigenic strains, as a rule, remain in the intestinal lumen, only approaching the top of the villi.

References

Baldrian, P. (2019). The known and the unknown in soil microbial ecology. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 95(2), fiz005. Web.

Das, S., & Dash, H. R. (Eds.). (2018). Microbial diversity in the genomic era. Academic Press.

Denamur, E., Clermont, O., Bonacorsi, S., & Gordon, D. (2021). The population genetics of pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 19(1), 37-54. Web.

Harrington, V., Lau, L., Seddu, K., & Suez, J. (2021). Ecology and Medicine Converge at the Microbiome-Host Interface. Msystems, 6(4), e00756-21. Web.

Modha, S. (2022). Sequence data mining and characterisation of unclassified microbial diversity (Doctoral dissertation, University of Glasgow).

Talaiekhozani, A. (2021). Guidelines for quick application of biochemical tests to identify unknown bacteria. Account of Biotechnology Research, 2021. Web.

Thomas, A. M., & Segata, N. (2019). Multiple levels of the unknown in microbiome research. BMC Biology, 17(1), 1-4. Web.

Appendix

Before adding

After adding