Chapter 1: Introduction

Background

Gamification, defined in the literature as the use of game design components in non-game environments (Looyestyn, et al., 2017), is increasingly gaining prominence in institutions of learning as teachers continuously pursue new instructional strategies to replace traditional approaches perceived by many students as ineffective and boring (Dicheva, Dichev, Agre, & Angelova, 2015).

Although the application of gamification in education is still an evolving trend, there is a wide-reaching consensus among stakeholders that the concept is effective in increasing student motivation and engagement in learning contexts (Kim, 2015b). Indeed, according to Dicheva et al. (2015), the use of gamification as a learning instrument is a promising strategy due to the concept’s capabilities to teach and reinforce the internalization of knowledge and other important life skills, such as problem-solving, collaboration, and communication.

Research consistently supports the use of gamification in classroom contexts as providing added benefits in terms of boosting enthusiasm towards math and science subjects, lessening disruptive behavior, increasing cognitive growth, incorporating mature make-believes that enhance growth and development, and improving attention span through game-centric learning (Roberts, 2014; Bruder, 2015).

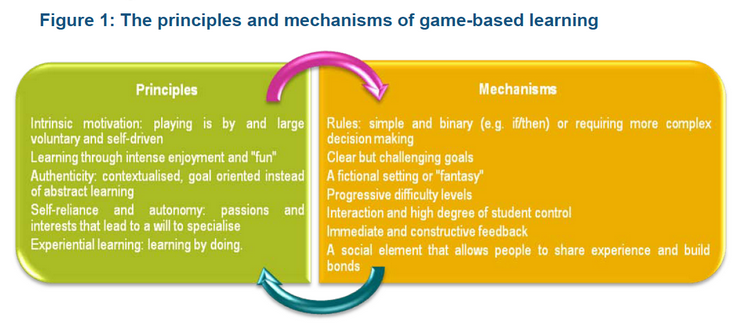

The game design elements that make gamification more motivating and engaging in educational contexts, according to these authors, include continuous challenges, interesting storylines, flexibility, immediate rewards, and the ability to combine fun with realism.

However, despite the perceived benefits, opinions on the factors that influence the adoption of education gamification have been mixed to date, and it is not clear yet how these factors inform the adoption process in distinct geographical environments (Looyestyn, et al., 2017). As such, the current research study is an effort to illuminate the factors that affect the implementation of gamification in learning contexts, its emergence, and consolidation in Abu Dhabi. This research study uses a sample of participants from Abu Dhabi’s higher education sector to identify the factors that affect the adoption of gamification in educational contexts in general.

Research Problem

Research consistently shows that traditional schooling techniques are no longer as effective as they used to be in previous eras due to their incapacity to provide student motivation and engagement (Dicheva, Dichev, Agre, & Angelova, 2015). Students in developed and developing economies are demanding more engaging and collaborative learning environments to keep in line with the emerging shifts in technological advances and competition patterns (Looyestyn, et al., 2017).

As such, there has been an ongoing shift from traditional education systems comprising a classroom of fifteen to thirty students with different strengths and weaknesses, towards a more digitized approach of instructional delivery which aims to motivate and engage students while boosting their enthusiasm for difficult subjects and increasing their cognitive growth (Bruder, 2015). In traditional schooling, students can often encounter difficulties in understanding their study books, which in turn increases their frustration, boredom and disinterest in the objectives of learning (Dicheva, Dichev, Agre, & Angelova, 2015).

The growing technology seems to attract children of every age, and especially those who like to play games more in comparison to spending time on book-based study. Recently, there has been an influx in the presentation of course content using the gamification technique with the view to motivating students and ensuring that they become more engaged with their lessons (Kim, 2015c).

The main objective of using the gamification technique in educational contexts, it seems, is to optimize enjoyment and engagement by not only capturing the interest of students, but also stimulating them and, thus, encouraging continuous learning.

Gamification “can function as a win-win strategy that results in fun, self-improvement for individuals, and even a social good all at the same time when it is carefully designated to create fun and joy with a goal closely aligned with players’ own desires and values” (Kim, 2015a, p. 20). This is consistent with the description offered by Bruder (2015), who explains gamification in terms of the utilization of game based mechanics, aesthetics and game thinking for engaging people, motivating their actions, promoting learning, and solving problems.

Research Aim and Objectives

The main aim of this research study was to undertake a quantitative investigation of the factors that influence the adoption of education gamification in Abu Dhabi. The following were the specific research objectives:

- To determine the main factors that affect the adoption of education gamification in Abu Dhabi;

- To analyze the challenges facing the adoption of education gamification in Abu Dhabi, and;

- To recommend strategies aimed at facilitating the adoption of education gamification in Abu.

Research Questions

The main research question for this particular study was as follows: What factors affect the adoption of gamification in learning contexts in Abu Dhabi? The supporting research questions were as follows:

- RQ1: What are the factors that influence the adoption of education gamification in Abu Dhabi?

- RQ2: What are the perceptions and viewpoints of Abu Dhabi students regarding the application of gamification in learning contexts?

- RQ3: What are the challenges to the successful implementation of gamification by institutions of higher learning in Abu Dhabi?

Significance of the Research

This study is significant because the data and findings will add to the inadequate quantitative data already existing on the factors that influence the adoption of education gamification in the Arab educational context and the challenges experienced by students when it comes to the adoption of education gamification. Indeed, the perceptions and viewpoints provided by students enrolled in institutions of higher learning in Abu Dhabi could help stakeholders in the education sector to develop and implement policy frameworks that will facilitate the adoption of education gamification in the wider educational context.

This is in line with the realization made by several researchers about the value of game-based education in stimulating students and engaging their attention (Huang & Soman, 2013; Malyakkal, 2014). Additionally, information could be drawn from this study to assist students and educators to increase their awareness about the potential benefits offered by education gamification, which in turn could increase the uptake of the game-based pedagogical approach in institutions of higher learning.

In addition, these findings may have significance for education stakeholders charged with the responsibility of coming up with ways and strategies that could be used to address the challenges associated with the adoption of gamification teaching and learning methodologies in educational settings. Factually, the study’s capacity to offer a detailed analysis of the factors that affect gamification in learning contexts means that schools can use the accumulated knowledge to address the challenges identified and take advantage of gamification.

Scope of Research

The study focused on education gamification among institutions of higher learning in Abu Dhabi by examining factors that influence its adoption, perceptions and viewpoints of students regarding the application of gamification in learning, and challenges that hinder successful education gamification. To obtain the data, the study surveyed students in institutions of higher learning in Abu Dhabi, which offer certificate, diploma, degree, masters, and doctorate courses in the fields of IT sciences, health sciences, education, applied communication, arts and design, and engineering amongst others.

Learning institutions examined are HCT, ZU, UAEU, INSEAD, KUSTAR, MIST, Sorbonne University, ADU, ADSM, and other colleges. Moreover, the students examined represented both genders, different ages, employed or not employed, and single or married. In essence, students surveyed had different demographic variables implying findings reflect the diversity of students in the United Arab Emirates. As the best tools used in gamification, the study examined usage video projector, presentation slides, simulation, video conferencing, flipcharts, whiteboard, and smart board. As for delimitation, the collected data are limited to the understanding of gamification among students. Additionally, the study collected only primary data and used them in data analysis in line with research objectives.

Research Assumptions

Overall, the researcher made the following assumptions:

- The structured survey instrument used to collect data from the field is an accurate measure of perceptions regarding the factors that influence the adoption of education gamification in Abu Dhabi,

- Participants sampled for the study responded accurately and honestly to the survey,

- Data received from the administration of the structured survey provide an accurate representation of students’ perceptions about the factors that influence the adoption of education gamification in Abu Dhabi,

- The only variables studied were representative of the stated research objectives and questions, and

- This study was specifically limited to the attitudes and perceptions of students enrolled in institutions of higher learning in Abu Dhabi.

Chapter 2: Literature Review

Introduction

In reviewing the extant literature on the topic of gamification, a multiplicity of philosophical and professional research articles, books and other scholarly documents were used to explain the premise behind the proliferation of this concept in both business and educational contexts. However, significant studies on student perceptions about the factors that appear to influence the adoption of education gamification, as well as what educational institutions could do to address the challenges emanating from transitioning to a game-based pedagogy, were lacking. The objectives of this review were as follows:

Identify gamification trends worldwide,

- Identify and explain gamification trends within the specific UAE context,

- Explore how education gamification is being adopted in Abu Dhabi, and

- Summarize the literature reviewed based on the factors and challenges used in the development of the questionnaire.

Gamification Worldwide

Gamification is the application of typical tools of game playing to the areas of activities, such as education and marketing. It is more like a typical online marketing technique for persuading customers to buy products and services (Lee & Hammer, 2011). A projection made in 2013 by a leading advisory company in information technology demonstrates that, by 2015, 40 percent of global 1000 organizations were likely to make a switch to gamification as the most important instrument for transforming their business operations, and 50 percent of these organizations we likely to be using the concept for learning and recruitment by the end of 2017 (Arabian Gazette, 2013).

Gamification is an active learning technique that ensures students remain engaged in what they are doing, hence assisting them to “move away from being spoon-fed facts and figures to developing concepts, understanding principles and applying knowledge in practice” (Day-Black, Merrill, Konzelman, Williams, & Hart, 2015, p. 90). In the United States, for example, a charter school known as Quest2Learn has attempted to gamify the whole school system by making the entire learning process into a game and using elements such as boss levels, quests, missions, avatars, and incentives to motivate and involve students (Kim, 2015b).

This school employs games as rule-based learning systems, developing “worlds where players take on identities and behaviors of appropriate characters such as explorers, mathematicians, historians, writers, and evolutionary biologists; use strategic thinking to make choices; solve complex problems; seek content knowledge; receive constant feedback; and consider the point of view of others” (Kim, 2015b, p. 7). Indeed, as noted by this particular researcher, the potential for gamification as a learning tool is increasingly attracting interest from institutions in the United States, as well as globally.

A researcher interviewed five leaders from the academic background and shared a game-based learning model because of the size and inertia of the public education system and transformation process in the current culture and society (Titthasiri, 2013). The author explained that traditional learning concepts are focused on large concepts and structures. Students get disinterested and bored from studying books and following the same route of education every day.

The students start getting distracted and prefer playing video games or any outdoor games instead of reading books. The traditional learning process emphasizes on the individual student work. Students under this model receive fewer opportunities for practicing the group dynamics. This traditional model of learning parallels what may be desired in contemporary educational settings as demonstrated by educational researchers (Lee & Hammer, 2011), who found that present-day students are more likely to engage themselves in online games rather than interact with other students in real-life environments by virtue of growing up surrounded by computers and the Internet. In their study, Caponetto, Earp, and Ott (2014) reinforced the argument made by Lee and Hammer (2011) by arguing that the students’ desire to engage in e-learning experiences is embedded in three justifications, namely:

- Desire to be interconnected with each other,

- Aspirations to be entertained through the games and movies, and

- Desire to present themselves and their work through online protocols.

Overall, these authors shared a perception that gaming technology will surely replace the standard classroom lectures and tests in the future due to its “fun” component.

Gamification in the UAE

Gamification is increasingly taking root in the UAE, as demonstrated by a news article showing that “Gamification, Personal Virtual Assistant and The Local Programmer are among the new initiatives that the Hamdan Bin Mohammed Smart University (HBMSU) has developed” (Khaleej Times, 2016). The article further states that, with the help of gamification, the journey of learning and gaining knowledge can be made quite effective and fun based. The fact that HBMSU has adopted gamification shows that the UAE has become one of the countries to initiate gamification in the educational process.

The article also underscores the fact that, while traditional methods of teaching are not making a substantial impact on contemporary learning processes in the UAE, gamification is increasingly turning learning into an enjoyable and pleasurable experience by making it more interesting, challenging, and exclusive (Khaleej Times, 2016).

This view is shared by Kopcha, Ding, Neumann, and Choi (2016), who found that the gamified approach to a graduate level course on technology integration was effective in providing students with the needed motivation, recognition and autonomy through the use of badges, awards, and the opportunity to customize course experiences to their own interests.

According to Dicheva et al. (2015), one of the drawbacks of traditional learning relates to the fact that it places more value on standards and curriculum as opposed to student-focused learning. Traditional learning, according to these authors, is mainly based on repetition and memorization of the facts that students really do not care about, thus the knowledge retention rate is quite low after testing. Jordan (2012) noted that the learning of the 20th century used to focus mainly on the acquisition of the basic literacy skills.

In comparison, the 21st century learning structure, along with the proliferation of novel technologies, should rather focus on the attainment of high literacy skills such as complex problem solving skills and the dynamic expressions with language and media (Jordan, 2012). The shift in focus provides a window of opportunity for educators in the UAE and other countries across the world to use game-based pedagogy to satisfy three innate psychological needs related to learning, namely relatedness (supported by and supporting others), autonomy (having a perception of willingness, agency, and congruence with our self in what we do), and competency (having the perception that we can affect change in the world, and that we get better at that) (Deterding, 2013).

In his research, Whyte (2013) explained that gamification in education is not just about layering the goals and rewards on the top of the content; rather, it also involves the adoption of the games utilities and thinking mentality for integrating the mechanism into learning in the planned approach. The author further noted that effective games influence the psychology and technology in varied ways that can be applied outside the environments of the games.

These views are consistent with the arguments made by other researchers, who have acknowledged that gamification allows the student to gain a multiplicity of skills through a series of psychological exercises and games that motivate repetition and competition (Suvajdzic, 2016). It is also stated by some that the game-based pedagogy provides mental stimulation and a means of engaging students to acquire, and develop, an in-depth understanding of academic subjects (Barlow & Fleming, 2016). Finally, researchers conclude that the fun in gamification is engineered by four building blocks, namely goals, rules, a feedback system and voluntary participation (Kim, 2015b).

Contrary to the viewpoints discussed above, the concept of gamification of learning has been criticized for its usage of extrinsic motivators, which some of the teachers believe should be avoided as they have the potential for decreasing the intrinsic motivation for learning. Indeed, some educators have criticized gamification for taking a less serious approach towards education (Perrotta et al., 2013). This may be the result of the historic distinction between work and play, which perpetuates the notion that the classroom cannot be a place for game.

Many people feel that gamification in education is not worth their time for implementing the gaming initiatives, in large part because of the fact that teachers are overstretched and overworked with varied responsibilities. Additionally, gamification of learning has been criticized for being ineffective for certain types of learners and in certain situations (Perrota, Featherstone, Aston, & Houghton, 2013).

In their study, Day-Black et al. (2015) found that education gamification is often faced with the challenges of lack of appropriate tools and broadband Internet services, educational contexts that cater to students not considered to be members of the “digital” generation, and incapacity or unwillingness of students to independently complete their reflective assessments after engaging in game-based pedagogy.

Similarly, Looyestyn et al. (2017) noted the challenges of education gamification to sustain the positive effect associated with gamification. The novelty of extrinsic rewards, such as badges and points, tends to wear off after a short period of time. Coupled with this is a lack of meticulous research designs to determine the effectiveness of gamification in different educational settings, and a lack of appropriate discussion among experts and professionals to support consistent reporting of gamification features or components.

Overall, gamification is widely accepted both in the field of education and business. Indeed, employers have started using gamification to make work enjoyable and also to bring the fun element which leads to employee engagement and motivation. The level of students’ acceptance of gamification is also high (Squire, 2015). Female students can be persuaded towards engaging in more computer based games.

It is argued that the lack of interest in traditional methods of learning is the main reason behind the acceptance of gamification among students in contemporary educational settings (Plass, Homer, & Kinzer, 2015). Besides this reason, it is evident that the overall acceptance of education gamification can only intensify into the future owing to the fact that students today are more inclined towards the use of games and the fun element in their studies (Harmon & Copeland, 2016; Malyakkal, 2014).

Gamification in Abu Dhabi

Abu Dhabi also is moving with the slowly, though some schools as well as business organizations operating there have greatly acknowledged the use of gamification in their operations. The significance of making education fun can clearly be observed in a newsletter of a leading prep school in Abu Dhabi (Cranleigh Abu Dhabi Prep School, 2016).

Furthermore, in order to promote gamification, a new venture has been launched by the name Gamified Labs which concentrates upon interactive media and consultancy related to gamification (Dakkak, 2014).

In their contribution to a leading book on how mobile learning could be used to motivate and engage students studying science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) subjects, Khaddage and Lattemann (2016) made mention of how institutions of higher learning in UAE including Abu Dhabi are experimenting with gamification to not only guarantee the creation of fun and excitement in the learning process, but also to increase student productivity, engagement, corroboration, and creativity.

The main game mechanisms used by these institutions, according to these authors, include goals (a list of tasks to be completed in order to achieve specific goals), achievements (task rewards set as external elements with the view to rewarding students with points or status symbols), problem-solving skills meant to show progress and act as a status indicator, badges meant to make users feel that there is value to their actions, and progression meant to provide proper feedback to users through statistics, progress bars, or other means with a view to instilling a sense of engagement and belonging.

As acknowledged, gamified learning is currently in the early experimental stage, and incorporating the main design elements in the current course content is not an easy task (Bartel & Hagel, 2016). The e-learning research method is slowly evolving the usage of game-based platform and is becoming more and more popular. The e-learning system is advantageous as it incorporates the computer assisted learning tools as the stand-alone technology based training programs and exercises (Ozcelik, Cagiltay, & Ozcelik, 2013).

Apart from the reasons discussed above, these authors illuminate more justifications by arguing that education gamification provides the opportunity for students to make their own decisions and evaluate the impact of their decisions. In a study aimed at evaluating the effectiveness of gamification on higher education students’ engagement, motivation and academic attainment within the Abu Dhabi context, Taylor (2015) observed that the gamified approach to learning could be used to teach English as a second language since many students demonstrate a focused lack of motivation, interest and engagement by virtue of the fact that Emirati students are taught Arabic at school and are only introduced to English-related courses upon enrollment in one of three government-funded higher education institutions where undergraduate and postgraduate units are delivered through the medium of English.

Vleeshouwer (2015) did a study on the factors affecting the implementation of gamification in learning. Upon analysis of the field data, this researcher found that the factors of expectancy in performance, expectancy in effort, social influence, facilitating factors, change resentment, and perceived satisfaction affected the implementation of gamification in learning.

Performance Expectancy, according to Vleeshouwer (2015), is the degree to which the student perceives that utilizing gamification will enhance their studies, while effort expectancy is the degree to which the student perceives that utilizing the gamification application is effortless. Vleeshouwer (2015) defined social influence as the degree to which the individual perceives that he should utilize the new system, while perceived enjoyment was defined as the degree to which the student perceives the usage of gamified learning to be enjoyable.

Available scholarship defines change resentment as the factor which will be seen while implementing the gamification in institutions (Dent & Goldberg, 1999); that is, the degree to which the elements of game design adopted by institutions may cause some generalized resentment among users to actively involve themselves in meaningful play (Gilbert, 2016).

Research consistently demonstrates that employees and students in business organizations and institutions of learning will have to adapt their style of learning in the event that gamification is implemented within their settings (Toribio & Hernandez, 2011). Owing to the fact that many individuals are resistant to change, preferring to maintain the status quo (Brown, 2009; Dent & Goldberg, 1999), business and educational organizations may find it difficult to introduce gamification due to the resistance that may come from the people affected by the changes (Chang & Wei, 2016).

Indeed, as demonstrated by Brown (2009), many individuals will resist change efforts implemented by an organization as they are used to their traditional working styles. In educational contexts, teachers may resist the changes brought about by gamification due to a perception that they will be forced to undergo new training (Barlow & Fleming, 2016; Kopcha, Ding, Newmann, & Choi, 2016). Available scholarship clearly highlights the importance for teachers and staff members to undergo training on game-based pedagogy for them to fully understand the advantages of gamification in learning (Chang & Wei, 2016).

However, it is possible that gamification projects in institutions of learning may encounter resistance as the educators and other staff members fight to maintain the status quo, particularly in terms of ensuring that traditional teaching methods are not replaced with new, technology-based concepts such as gamification (Barlow & Fleming, 2016; Kopcha, Ding, Newmann, & Choi, 2016).

In his study, Marquis (2012) found that lack of usable tools, lack of teacher expertise, and lack of clear objectives are the main factors that affect the performance of gamification in educational contexts. Gamification, according to this particular author, requires a proper infrastructure that is nonexistent in many institutions of learning. Marquis (2012) further emphasized that, since the concept is new, there is a high probability that teachers in schools are not aware of the design elements and expertise needed to fully operationalize gamification as a learning tool.

This means that educators and other stakeholders in institutions of learning lack the skills and knowhow of delivering an elaborate integration of games into the curriculum since many of them are yet to be trained on game-based pedagogy. Khaddage and Lattemann (2016) presented a different view by arguing that current gamification projects will continue to fail by huge percentages, despite preliminary studies showing high potential in the use of gamified applications for learning and teaching STEM subjects, in large part due to poorly designed models and lack of concrete frameworks that could be applied in designing the applications.

Utilizing games in the classroom needs a rethink regarding the student-teacher relationship, a new model for the ownership of the task, and complex structures for support of learners (Marquis, 2012). This author underscored the fact that, although the idea of meaningful activity encourages the motivation and engagement of students and is fundamental to gamification, the concept is still surrounded by issues and challenges that need to be resolved.

Indeed, Marquis (2012) noted how it would be a big mistake to make the assumption that gamification is an individualistic concept as similar mechanisms can and have been utilized to encourage and sustain collaborative and cooperative behaviors. The institutions for encouraging the development of communities have mainly embraced gamification and also applied the concept to situations that are beyond the scope of gamification.

In addition to the above factors, gamification is helpful in encouraging people to perform administrative tasks and exercises. However, it is a complex concept and researchers have yet to fully document its successes or effectiveness in educational settings, largely due to the various identified factors that affect its performance (Marquis, 2012).

According to a research study by Grath and Bayerlein (2013), the current generation of students is fundamentally different from previous generations because of shifts in media consumption patterns. This new generation is now growing up immersed in an Internet and video game environment. Hence, the argument that contemporary students have been able to achieve highly specialized technical skills and why they show a preference for diverse learning that warrants a new educational approach.

As demonstrated by Grath and Bayerlein (2013), computer-based games have excelled in the creation of an illusion of autonomy from the highly structured rule-based contexts that characterize traditional learning and teaching. However, despite this significance, Grath and Bayerlein (2013) underscore the fact that students in contemporary educational settings may perceive gamification in the same context as video games since they are particularly fond of the latter.

As such, these students may get dissatisfied and at times disinterested when they realize that gamification is actually related to studies. Another author acknowledges the fact that learning and losing do not go together (Bruder, 2015). The perspective of losing, according to this author, may affect students’ learning processes since the main objective of education should be to motivate students to perform better.

Summary

The table below provides summary of the literature by showing factors and their respective citations and notes for each research question.

Table 1: Shows Research Questions, Factors, Citations, and Notes.

The sources reviewed in this chapter expanded the knowledge of the researcher regarding the factors that are driving the adoption of education gamification and the challenges that educational institutions continue to face as they take up this promising concept. Wide research consistently demonstrates that traditional educational learning and teaching methods are increasingly becoming boring, disinteresting, and ineffective as they used to be, hence the need to adopt gamification with the view to motivating and engaging students.

Unlike traditional learning processes, education gamification has the capacity to provide students with the needed motivation, recognition and autonomy, while increasing their productivity, engagement, corroboration, and creativity through the use of badges, awards, and the opportunity to customize course experiences to their own interests. Additionally, contemporary students are more oriented towards digitized learning environments as opposed to more traditional learning processes that are often viewed as failing to ensure that students gain high literacy skills.

The fun component that characterizes gamification has also been credited for turning learning into an enjoyable and pleasurable experience by making it more interesting, challenging and exclusive. Furthermore, research is consistent that education gamification may find wide usage and acceptance in the future, not only because of students’ desire to be interconnected with each other, but also due to their ambition to be entertained through games and movies. Other factors identified in the literature as driving the adoption of gamification include expectancy of performance, expectancy of effort, social influences, facilitating factors, change resentment, and perceived satisfaction.

The challenges for the successful adoption of gamification in educational contexts are manifold largely because the concept is new, thus teachers are not aware of the design elements and expertise needed to fully operationalize gamification as a learning tool. Gamification has also been accused of taking a less serious approach towards education, with some researchers arguing that its use of extrinsic motivators decreases the intrinsic motivation for learning, that students cannot be able to learn by losing, and that gamification is ineffective for certain types of learners (e.g., elderly students not considered to be members of the digital generation) or in certain situations (e.g., classroom contexts with no broadband Internet connection or where teachers are unable to use gamification due to their lack of expertise).

Further, teachers may resist the changes brought about by gamification due to a perception that they will be forced to undergo new training on the concepts of gamification. Other challenges noted in the reviewed literature sources are as follows: lack of clear objectives for gamification; lack of usable tools; existence of poorly designed gamification models; lack of concrete frameworks that could be used to design gamified applications; the inability to sustain the positive effect associated with gamification based on the fact that the novelty of extrinsic rewards, such as badges and points, tend to wear off after a short period of time; lack of meticulous research designs to determine the effectiveness of gamification in different educational settings; and lack of appropriate discussion among experts and professionals to support consistent reporting of gamification features or components.

Chapter 3: Research Methodology

Introduction

The research methodology not only shows how the researcher intends to carry out the research, but also helps in understanding the reasons behind the selection of particular methods and approaches (Creswell, 2014). This chapter describes the research methods and methodologies that were used to undertake this study, including the research approach, study design, survey design and distribution, and data collection methods. Issues of research ethics and time-frame are also discussed here.

Research Approach

This study used a quantitative research approach comprising a systematic examination which made use of computational tools and techniques to provide responses to questions that pertained to establishing the factors that influence the adoption of education gamification in Abu Dhabi (Creswell, 2014). Quantitatively, the results were analyzed statistically with some numbers, percentages, and charts using MS Excel in order to come up with meaningful results that could be understood easily from a management perspective.

It is important to note that the quantitative research approach allowed the researcher to reduce the independent variable (education gamification) and the dependent variable (students’ perceptions) to numerical values that were then used to investigate the factors that influence the adoption of education gamification in Abu Dhabi (Gelo, Braakmann, & Benetka, 2008; Yilmaz, 2013).

Research Design

This study used a descriptive (survey) research design by virtue of the fact that the sampled participants were contacted at a fixed point in time to collect important field data on the factors that influence the adoption of education gamification in Abu Dhabi (Creswell, 2014). As postulated by Welford, Murphy, and Casey (2012), “a survey provides numerical description of trends, attitudes or opinions of a population by studying a sample of the research population (p. 34).

In using this research design, the researcher was able to use a structured survey questionnaire to generate quantitative descriptions of significant aspects of the studied population, particularly in terms of investigating the students’ perceptions of adopting education gamification in Abu Dhabi (Creswell, 2014).

The second justification of using this research design is embedded in its capacity to enable the researcher to develop numeric descriptions of attitudes and perceptions of education gamification in Abu Dhabi that could be generalized to the whole population of students in institutions of higher learning, based on the fact that the data generated from the sample are grounded on real-world observations (Sekaran, 2006).

Survey Design and Distribution

The survey used the questionnaire method of data collection to investigate the perceptions of students on the factors that influence education gamification in Abu Dhabi. In the construction of the survey, an introductory statement was used to not only provide a brief summary of the survey’s purpose but also to guarantee participants’ of their confidentiality and motivate them to complete the survey (Collie & Rine, 2009).

The researcher also ensured the construction of effective questions by including directions for completing the survey, providing a defined objective for each question, eliminating any unnecessary questions, paying close attention to wording to avoid double-barreled questions, and evaluating the survey prior to administration through piloting the survey to 6 participants (Creswell, 2014).

Closed-ended questions were used to ensure that participant responses were easily standardized and analyzed statistically. However, the researcher took care to ensure that pertinent information was not missed by providing as many responses as possible, including the use of the “other” response option. Categorical-type questions were used to collect demographic and conceptual information, while Likert-type questions (e.g., 1= strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree) were used to collect the perceptions and attitudes of students on the factors that influence the adoption of education gamification in Abu Dhabi. Categorical-type questions helped the researcher to collect data where the respondent belonged to only one of a set of possible categories, while Likert-type questions helped the researcher to measure attitudes and perceptions using numerical rank options (Collie & Rine, 2009).

Overall, the questionnaire was divided into five sections, as follows: section 1 included demographic questions; section 2 aimed to find out the preference of participants towards the usage of technology; section 3 aimed to check the awareness of participants with regards to gamification; section 4 intended to determine participants’ perceptions of the challenges and benefits related to gamification; and section 5 intended to measure the level of participants’ acceptance of gamification in education. The students were required to fill the questionnaire through a self-administered process. Table 2 below maps research questions to sections, questions, and Likert statements in the questionnaire created.

Table 2: Reflection of Research Questions in the Questionnaire.

The questionnaire was used as the primary method of data collection due to:

- Time and cost efficiencies,

- its demonstrated capacity to reduce bias which is often associated with researcher characteristics and variability in interviewer skills, and

- Its capacity to provide a high degree of anonymity to study participants due to the absence of the interviewer in the actual completion of the task (Fowler, 2008; Polonsky & Waller, 2010).

After the approval, the questionnaire was shared with the students by making a personal visit to the institutes’ student services and requesting to distribute the link to the student’s email, visits to recruitments exhibits and job fairs, and some organizations. The questionnaire was mainly distributed through email, not only because of its cost-effectiveness but also due to the fact that it is the fastest method of distribution (Creswell, 2014), few manual copies where printed when necessary.

The population of this study comprised students in institutions of higher learning in Abu Dhabi. A convenience sampling strategy was used to select the participants for the study based on their availability. This non-probabilistic sampling strategy was used not only because of its predisposition to provide the researcher with a way to select the most available respondents to take part in the study, but also due to its ease of administration and capacity to gather important data that may prove difficult to collect using probability sampling approaches (Sekaran, 2006). The sample size taken for the survey was based on the number of the student’s population in the higher education entities in Abu Dhabi, which has three different units (Federal HEIs, Public Non-Federal HEIs, and Private HEIs) as shown in Table 3 below.

Table 3: List of Higher Education Institutions.

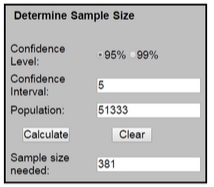

According to the UAE’s Ministry of Education, currently there are 51,333 students enrolled in Abu Dhabi Higher Education Institutions, with expectation of 32,480 students to be added soon. Details of the students’ enrollment rates across the seven emirates forming the UAE are shown in figure 2, sourced from the UAE Higher Education Factbook.

As shown in Figure 2 above, the total number of students in higher education institutions in Abu Dhabi (the study population) is 51,333. The researcher used an online sample size calculator to determine the sample size using two different confidence levels. A screenshot of the results obtained from the online sample size calculator is shown in Figure 3, below.

Overall, the calculations from the sample size calculator showed that a sample of 381 students was adequate to generalize the findings of the population of 51,333 students enrolled in institutions of higher learning in Abu Dhabi. Based on the calculation (Figure 3) and the realization that the credibility of a study increases with the size of a sample (Creswell, 2014), the sample obtained is a representative of the population under study.

Data Collection Method

This research study used a fully-structured questionnaire instrument for the purpose of primary data collection. The questionnaire was developed around the main findings of the literature review, particularly with regards to investigating the attitudes and perceptions of students on gamification in learning and the factors that influence the adoption of education gamification in Abu Dhabi. The online questionnaire data collection method provided the researcher with the benefits of ease of administration, minimal cost outlays, ease of data analysis, and capacity to collect large amounts of data from a large number of geographically diverse students in a short duration of time (Creswell, 2014).

Research Ethics

The researcher took caution to address ethical issues and concerns as they arose during the data collection phase of the research process. First, the necessary approval forms to undertake a research study involving human subjects (sampled students from higher education institutions in Abu Dhabi) was sought from the university and filled out as required. Second, a letter seeking permission from the administration of the selected higher education institutions to collect data from students enrolled in these institutions was prepared, dispatched, and approved.

Third, an informed consent form with clear details on the nature/purpose of the study and the rights of participants (e.g., right to informed consent, right to withdraw from the research process at any time, right to confidentiality and anonymity, right to information, as well as right to non-discrimination during the research process) was prepared and sent to participants via their email addresses for perusal and signing (Semaan, Heckathorn, Des Jarlais, & Garfein, 2010).

Chapter 4: Research Results And Discussion

Introduction

The primary aim of this research study was to investigate the factors involved in the adoption of education gamification in Abu Dhabi. The study was also interested in investigating the perceptions of Abu Dhabi students with regards to the application of gamification in learning, and in developing an adequate understanding about the challenges to the successful implementation of education gamification.

Towards the realization of these main objectives, a survey was conducted with participants drawn from higher education institutes operating in Abu Dhabi. This chapter presents the main findings of the results using text, tables, and graphical representations, after which the results are discussed comprehensively based on the findings of other researchers and in alignment with the stated research questions for this study. It is important to note that the researcher received 485.

Demographic Characteristics

Of the 485 students who returned their questionnaires, 191 (39.4%) were male and 294 (60.6%) were female. This means that six in every 10 participants selected for the study were of the female gender. In nationality, 453 (93.4%) of the participants were UAE nationals, while the remaining 32 (6.6%) students came from different countries. Thus, the low number of students from other countries is a limitation because it reduces external validity of the findings. It is important to note that 184 (37.9%) of the participants were between 21 and 24 years old, while 113 (23.3%) were below 20 years of age. The full age distribution of participants is shown in Figure 4, below.

Figure 4 shows that 436 (89.9%) of the sampled participants could be referred to as ‘members of the digital era’ since they were born after 1983 and are yet to attain 34 years of age (Harmon & Copeland, 2016). In marital status, 343 (70.7%) of the participants were single, while 142 (29.3%) were married. These statistics mean that seven in every 10 of the sampled participants had no spousal obligations. For employment status, 192 (39.6%) of the participants were employed while 293 (60.4%) were not employed.

Participants’ Education

A descriptive analysis of the data using frequency distributions showed that 125 (25.8%) of the participants were in Zayed University, while 86 (17.7%) were in Higher Colleges of Technology (HCT), 85 (17.5%) at the United Arab Emirates University (UAEU), and a further 52 (10.7%) at Abu Dhabi School of Management (ADSM). The rest of the distribution is shown in Figure 5.

It is important to note that, of the 66 (13.6%) students who were listed as being enrolled in other institutions, 21 (4.3%) were in Al Khwarizmi International College, while 16 (3.3%) were studying at the Emirates College of Technology. In terms of educational level, about half of the participants (49.9%) were studying for their Bachelor’s degree program, while one-fifth (21.9%) were studying for their Master’s or other higher graduate degree program. The full distribution is shown in Figure 6, below.

With regard to the class major of participants, 123 (25.4%) reported that they were majoring in Business, while 67 (13.8%) were majoring in IT Sciences and 63 (13%) in Health Sciences. The total distribution is shown in Figure 7, below.

Gamification, Technology Applications, and Class Attendance Reasons

A descriptive analysis of the data using frequency distributions showed that 370 (76.3%) of the participants were aware of what education gamification means, implying that about a quarter of students (23.7%) did not demonstrate awareness as demonstrated in Figure 8 below.

Cross-Tabulation of Gamification Awareness

A cross-tabulation analysis was done to determine if demographic variables, namely, gender, nationality, age group, marital status, employment status, college, education level, and class major, associate with awareness of education gamification to demonstrate. Figure 9 below shows the distribution of gamification awareness among between male and female respondents.

Cross-tabulation shows that there is apparent association between gender and gamification awareness because 84.8% of males and 70.7% of females are aware of gamification. This finding means that males are more ware of gamification than females. Moreover, cross-tabulation between nationality and awareness of gamification indicates that there is apparent association.

Specifically, 77.5% of participants from the UAE are aware of gamification while 59.4% of participants from other countries are aware of gamification (Figure 10). The difference implies that students with the nationality of UAE are more aware of gamification than students with nationalities of other countries.

Figure 11 depicts that there is apparent association between age group and awareness of gamification among students. Essentially, gamification awareness increases with decrease in ages of students in various age groups. The cross-tabulation shows that 78.8%, 81.9%, and 85.2% of students who fall in the age groups of below 20, 21-24 and 24-28 respectively were aware of gamification. Moreover, 65.0% and 57.1% of students who fall in age groups of 29-33, and 34 or above were aware of gamification.

Cross-tabulation of marital status and gamification awareness depicts some association. Among married participants, 69.0% are aware of gamification whereas among single participants, 79.3% are aware of gamification, as shown in Table 4 below.

Table 4: Marital Status and Gamification Awareness.

In the aspect of employment status, cross-tabulation shows that it associates with gamification awareness. Among employed participants, 71.4% are aware of gamification while among unemployed participants, 79.5% are aware of gamification, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5: Employment Status and Gamification Awareness.

Cross-tabulation (Table 6) shows that the type of educational institution has some association with gamification awareness. Evidently, 61.5%, 69.0%, 69.2%, and 69.2% of participants in ADSM, AU, INSEAD, and Sorbonne University respectively were aware of gamification. Moreover, 80.2%, 81.2%, 81.8%, 69.2%, 78.8% and 76.3% of participants in HCT, KUSTAR, other universities, UAEU, and ZU respectively were aware of gamification.

Table 6: University/College/Institution and Gamification Awareness.

Cross-tabulation (Table 7) reveals that there is no apparent association between education level and gamification. The same proportion of participants with bachelor (77.3%) and diploma (77.9%) were aware of gamification. Moreover, participants with higher diploma had higher proportion of awareness (81.7%) than participants with masters.

Table 7: Education Level and Gamification Awareness.

Table 8 indicates that 68.8% and 17.6% of participants majoring in arts and design and other courses respectively were aware of gamification. Comparatively, 78.4%, 74.8%, 77.2%, and 77.8% of participants majoring in communication, business, education, and health sciences were ware of gamification. Participants who major in IT sciences (89.6%) and engineering (83.1%) had the highest proportions of awareness.

Table 8: Class Major and Gamification Awareness.

Learning Behavior

The study participants were asked to identify the best technology tools used in class from a selection of applications, namely video projectors, presentation slides, simulations, video conferencing, flip charts, whiteboards and smart boards. Slightly below half of the students (239; 49.3%) chose video projectors, while 195 (40.2%) chose smart boards and 168 (34.6%) chose presentation slides.

The rest of the distribution is found in Figure 12, below. However, being a multiple response question, it is important to note that most students demonstrated awareness in not just one, but three or four, technology tools used in contemporary education students to learn. This is an encouraging finding, based on the fact that education implementation can only be best achieved through multiple technology tools, applications, and concepts.

The study participants were also asked to identify the activities they engaged in themselves during their free time from a selection of playing computer/video games, browsing the Internet, reading e-books, and reading books. Two-thirds (321; 66.2%) of the participants spent their free time browsing the Internet, while 195(40.2%) played computer and/or video games. The rest of the distribution is shown in Figure 13, below.

Figure 13 above shows that only two in every 10 students (22.1%) passed their free time by reading books. This finding is important in demonstrating how traditional learning processes may be failing many students, particularly when viewed within the context of the fact that 321 (66.2%) of the respondents chose to spend their free time in digitized environments browsing the Internet.

The study participants were then asked to identify the reasons that drive them to attend class. It is interesting to note that seven in every 10 students (339; 69.9%) of the sampled participants attended class due to their interest in the course, while 172 (35.5%) believed they attended class due to college attendance requirements. Figure 14, below, presents the full distributions of responses.

Figure 14 shows that most of the students sampled to take part in this study attended class out of their own interest in the course, showing that motivation for class attendance was high. Only 82 (16.95%) of the participants put their attendance of class down to difficulties in understanding some subjects.

Factors affecting the Adoption of Education Gamification

The study participants were asked to respond to several statements intended to measure their attitudes and perceptions on the factors affecting the adoption of education gamification using a Likert-type scale. The mode values (the values that appear most often in the dataset) and frequencies are shown in Table 9 and Figure 12 respectively.

Table 9: Factors affecting Adoption of Education Gamification.

Table 9 shows that most of the participants who answered this question (n=469) agreed with the statements that the current teaching methods are outdated, that a lack of knowledge about gamification will hinder its successful implementation, and that the gamification concept needs more support from the faculty. It is interesting to note that most of the respondents who answered this question strongly agreed with the statement that the gamification concept is easy to understand.

In variability (Figure 15), it can be noted that a total of 82% of the 469 participants who responded to this question either agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that the gamification concept is easy to understand, while only one in every 10 students either disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement.

Similarly, 87.2% of the respondents either agreed or strongly disagreed with the statement that the gamification concept needs more support from faculty, compared with 2.1% of the participants who either disagreed or strongly disagreed. In the statement that the lack of knowledge about education gamification will hinder its implementation in education, 73.1% of the participants either agreed or strongly agreed, while only 8.5% either disagreed or strongly disagreed. Lastly, 62.9% of the participants either agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that the teaching methods used in contemporary learning contexts are outdated, while 10.5% either disagreed or strongly disagreed.

Challenges Facing Education Gamification

The study participants were asked to respond to several statements intended to measure their perceptions and attitudes about the challenges that continue to face education gamification. The mode values and frequency distributions for this question are shown in Table 10, Figure 16 and Figure 17 respectively.

Table 10: Perceived Challenges Facing Education Gamification.

Table 10 shows that most of the participants who answered this question (n=467) disagreed with all the statements posed by the researcher to identify the challenges facing education gamification in Abu Dhabi. Specifically, the participants did not view the statements as offering any challenges to the successful implementation of education gamification in Abu Dhabi.

In variability (Figure 13), nearly half of the respondents (48.8%) who answered this question either disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement that the lack of usable gamification tools/applications in learning is a challenge to the successful implementation of education gamification, while 26.6% either agreed or strongly agreed that this issue presented a challenge. Similarly, 50.3% of the participants either disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement that the lack of teacher expertise in gamification presented a challenge, while only 27% agreed or strongly agreed that this issue was a challenge.

In the statement on resistance towards change, two-thirds of the respondents (65.85%) either disagreed or strongly disagreed that this was a challenge to the successful implementation of education gamification, while only two in every 10 participants (20.3%) agreed or strongly agreed that this was a challenge. 65.1% of the participants either disagreed or strongly disagreed with the assertion that using extrinsic rewards/motivators presented a challenge to the successful implementation of education gamification, compared with 14.7% who either agreed or strongly agreed that this was a challenge.

Lastly, 63.6% of the participants either disagreed or strongly disagreed with the assertion that losing multiple times in gamified contexts presented a challenge, compared with 14.5% who either agreed or strongly agreed that this was a challenge.

Figure 17 shows that Likert items of challenges experienced in the implementation of gamification have varied average ratings. The average ratings show that students tend to agree that lack of usable learning gamification applications (M = 2.69) and lack of teacher expertise in gamification of education (M = 2.70) are challenges faced in the implementation of gamification. In contrast, the average ratings show that students tend to disagree that resistance towards change (M = 2.32), the use of extrinsic rewards (M = 2.2), and losing multiple times (2.37) are challenges faced in the implementation of gamification.

Students’ Perceptions and Attitudes on Education Gamification

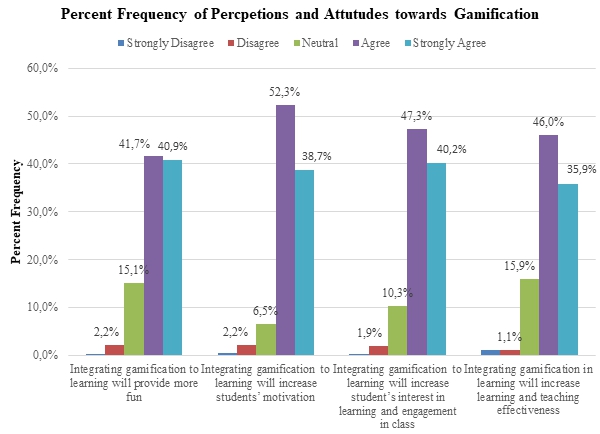

The study participants were requested to respond to several statements intended to measure their perceptions and attitudes on education gamification. During the designing of the survey questionnaire, the researcher assumed that the perceived benefits of education gamification can serve as major factors influencing the adoption of the concept in Abu Dhabi. The mode values and frequency distributions for this question are shown in Table 11 and Figure 18, respectively.

Table 11: Perceptions and Attitudes on Education Gamification.

Table 11 shows that most of the participants who answered this question (n=465) agreed that integrating gamification in learning could provide more fun and increase students’ motivation, interest in learning and engagement in class, as well as learning and teaching effectiveness. In variability (Figure 18), eight in every 10 students who answered this question (82.6%) either agreed or strongly agreed with the assertion that integrating gamification in learning would increase learning and teaching effectiveness, while only 2.2% either disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement.

Similarly, 87.5% of the participants either agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that integrating gamification in learning would increase students’ interest in learning and engagement in class, compared with 2.1% of the participants who either disagreed or strongly disagreed with this statement. Still, nine in every 10 students (91%) either agreed or strongly agreed with the assertion that integrating gamification in learning would increase students’ motivation, while 2.6% of the participants either disagreed or strongly disagreed with this statement. When asked whether integrating gamification would provide more fun, eight in every 10 students (82.6%) who responded to this question either agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, while 2.4% either disagreed or strongly disagreed with the assertion.

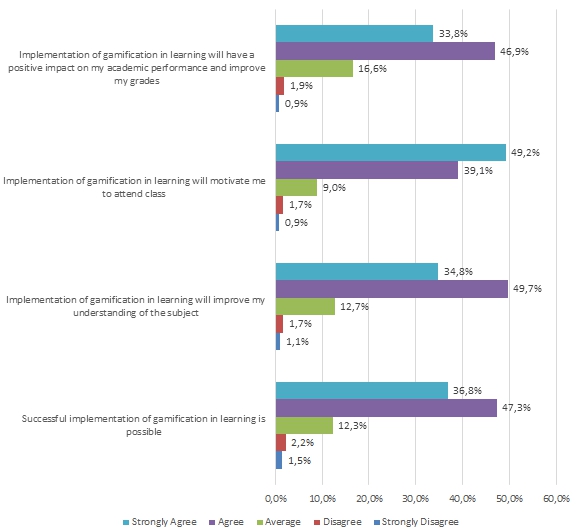

Lastly, students were asked to respond to another set of statements intended to measure their perceptions on the successful implementation of gamification in educational contexts within the Emirate of Abu Dhabi. The mode values and frequency distributions of their responses are shown below in Table 12 and Figure 19, respectively.

Table 12: Perceptions on Implementation of Education Gamification.

Table 12 shows that most of the participants who responded to this question (n=465) agreed with the statements that the implementation of gamification in learning is possible, will improve their understanding of the subject, and will have a positive impact on their academic performance and improve their skills. However, most students who responded to this question strongly agreed with the assertion that the implementation of gamification in learning will motivate them to attend class.

In variability (Figure 19), 84.1% of the participants who responded to this question either agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that the successful implementation of gamification in learning is possible, while only 3.7% either disagreed or strongly disagreed with this statement. A similar number of participants (84.5%) either agreed or strongly agreed with the assertion that the implementation of gamification in learning will improve their understanding of the subject, compared with 2.8% who either disagreed or strongly disagreed with this statement.

Nine in every 10 students (88.3%) either agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that the implementation of gamification in learning will motivate them to attend class, while 2.6% either disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement. Finally, eight in every 10 students (80.7%) either agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that the implementation of gamification in learning will have a positive impact on their academic performance and improve their grades, compared with only 2.8% who either disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement.

Discussion

The focus of this research study was to quantitatively investigate the main factors affecting the adoption of gamification in learning contexts in the Emirate of Abu Dhabi. In terms of background research findings, Figure 4 shows that most of the participants sampled for the study could be referred to as members of the digital era since they were yet to attain 34 years of age. As demonstrated in Figure 5, awareness of education gamification was dependent on age, with students in the digital era demonstrating more awareness of the concept than older students.

This finding is consistent with the observations made by Day-Black et al. (2015) and Harmon and Copeland (2016), suggesting that students in the digital era are more inclined to not only show awareness of education gamification, but also to adopt the concept in their learning processes. Additionally, this study confirmed the findings of other researchers (Chang & Wei, 2016; Kopcha, Ding, Newmann, & Choi, 2016), who noted that the awareness and knowledge levels of education gamification are dependent on the gender of the student. As demonstrated in Figure 9, males are likely to be more aware of what education gamification means than females.

This research study attempted to provide responses to three research questions, with the first being to investigate the factors that influence the adoption of education gamification in Abu Dhabi. As suggested in the problem identification section, many of the previous available studies have used only Western contexts within which to investigate these factors, hence the need to investigate them specifically within the Arab world.

It is evident from the findings presented in Table 9 and Figure 15 that the need to change traditional teaching methods that appear outdated to the young generation will continue to influence the adoption of education gamification into the future. Additionally, it is evident that lack of knowledge and expertise about education gamification will continue to hinder its successful adoption.

The level of faculty support will also determine the adoption of education gamification, as demonstrated by the fact that most of the participants recruited to take part in this study agreed with the statement that the gamification concepts needs more support from faculty. Overall, these findings are consistent with those of other researchers, who have found the static nature of traditional learning methods, as well as lack of knowledge and support from key stakeholders, to have a significant influence on the successful implementation of gamification in educational contexts (Barlow & Fleming, 2016; Dicheva, Dichev, Agre, & Angelova, 2015; Kopcha, Ding, Newmann, & Choi, 2016; Plass, Homer, & Kinzer, 2015).

The second research question attempted to investigate the perceptions and viewpoints of Abu Dhabi students regarding the adoption of gamification in learning contexts. This research question was influenced by assertions made by several researchers (Marquis, 2012; Chang & Wei, 2016; Barlow & Fleming, 2016) to the effect that gamification does not have any value in the delivery of education to students.

Contrary to these assertions, this study found that most students believed that integrating education gamification within learning contexts will provide more fun, increase students’ motivation, enhance their interest in learning and engagement in class, as well as facilitate overall learning and teaching effectiveness (see Table 11 and Figure 18).

Barlow and Fleming (2016), Chang and Wei (2016), and Day-Black et al. (2015) also found similar findings in their respective studies. Additionally, this research study found that the sampled students shared extremely positive perceptions on education gamification and its benefits. Specifically, the participants agreed that the successful implementation of gamification in learning is not only possible, but will also help them in improving their understanding of the subject, achieving the needed motivation to attend class, and impacting positively on their academic performance and grades (see Table 19 and Figure 12).

These findings collaborate those of Khaddage and Lattemann (2016), who noted that institutions of higher learning in Abu Dhabi and other Emirates in the UAE are experimenting with gamification to not only guarantee the creation of fun and excitement in the learning process, but also to increase student productivity, engagement, corroboration, and creativity.

Lastly, the third research question attempted to illuminate the challenges to the successful implementation of gamification by institutions of higher learning in Abu Dhabi. The main concern informing this research question was that, although many studies have been done in Western contexts with the aim of identifying these challenges, their findings may not be homogenous to those that may be found in the UAE due to a wide range of factors, including cultural- and religious-based value systems.

True to this assumption, the findings of this study showed that most participants disagreed with the fact that the adoption of education gamification could be affected by challenges such as lack of usable gamification tools/applications for learning, lack of teacher expertise in education gamification, resistance towards change, and losing multiple times (see Table 10 and Figure 16). These findings are not consistent with the results of other studies that have found these challenges to influence the adoption of gamification in learning contexts.

However, the disconnection in findings may be explained in terms of the cultural- and religious-based values and attitudes found specifically within the UAE, the researcher’s predisposition to recruit highly educated participants into the study (71.8% of the participants were pursuing their Bachelor’s, Master’s, or higher graduate degree programs, as demonstrated in Figure 6), and the sampling deficiencies that ensured the recruitment of more females compared to males. Highly educated students may be unable to identify with these factors as most of them are already knowledgeable about education gamification, while females demonstrate less awareness of education gamification compared to males, at least according to the results outlined in Figure 9.

Chapter 5: Recommendations And Conclusion

Recommendations

The recommendations outlined in this section target various groups: learners, learning institutions, and communities. Learners should pay specific attention to the integration of gamification in their curricula at school while learning institutions should ensure that learners have access to gamification applications during their learning process. Finally, communities should collaborate on including gamification in curricula by involving other parties such as students, parents, teachers, and administrators.

Recommendation to Learners

The findings indicate that learners are eager to integrate gamification into their learning process. Learners furthermore believe that specific barriers, such as a lack of gaming applications or a scarcity of teachers who are experts in this approach, do not adversely influence the integration process. It is possible, however, that these factors were not perceived as challenges due to the fact that the participants in the study tended to be well educated and had chosen to pursue a university degree. The recommendations would then be the following:

- Learners should keep abreast with technological advancements in education by playing computer games, browsing the Internet, and reading online e-books.

- As gamification increases motivation, interest, enjoyment, engagement, and learning effectiveness, learners should integrate it in their learning lifestyles.

Recommendations to Learning Institutions

As the participants of this study indicated, learning institutions currently lack specifically designed and usable gamification applications that could be integrated into curricula. A recommendation that naturally arises from this is therefore that learning institutions need to provide training or workshops to teachers who are not yet able to launch an effective gamification process:

- Educational institutions should build capacity for education gamification by providing usable learning gamification applications and training of teachers to equip them with the knowledge and skills necessary for the successful implementation of gamification.

- Advocate for the integration of education gamification in teaching and learning processes of students to improve productivity and performance of learners in the class.

Recommendations for Communities

Although the students who took part in the interviews did not view resistance to change as a major challenge for the implementation of gamification, gamification nevertheless faces other challenges. As the students agreed that gamification could make the learning process fun and more entertaining, educational communities should be aware of how beneficial this approach might be both for learners and teachers, as well as for other members of the community. The proposed recommendations include:

- Given that the adoption and implementation of education gamification face some resistance, parents and community members should advocate for gamification among learners to increase awareness and consequently lessen resistance experienced.

- Educational community comprising students, teachers, administrators, and policymakers ought to collaborate in designing a curriculum that incorporates gamification in the conventional teaching and learning methods.

Recommendation for Future Research

- Since the findings of the current research have limited external validity because it sought the views and perceptions of students only, future research should consider collecting data from faculty members, administrators, education experts, policymakers, and students from other nationalities to boost external validity of the findings.

- Future research should also use the qualitative approach and open-ended questions to allow respondents provide diverse responses to the current questionnaire limited them to the provided Likert items.

Conclusion

The student’s motivation to gain knowledge can be hindered if teaching and learning processes take place in outdated environments. However, with the advancement of technology, mundane learning contexts can be effectively converted into an addictive process of learning. Gamification is one such technique, which helps in bringing about a change of behavior in a student. Indeed, most instructors are using this technique to enhance the level of motivation and engagement of a student in the course of their learning process.

The outcomes of this research study reveal that most students in Abu Dhabi institutions of higher learning are aware of what gamification is and the role that is being played by gamification in the field of education. The use of the Internet and computer technology has also increased it recent times, which in turn has led to the development of education gamification in Abu Dhabi. According to the findings reported in this study, most of the students believe that the concepts related to gamification are easy to understand, though they require the support of instructors for them to be implemented effectively.

Furthermore, most students are of the opinion that that the existing methods of education have become outdated, thus the need to replace them with technology-based methods that serve the needs of present-day learners while motivating them to attend class and enhancing their performance and productivity. Overall, it is clear that the adoption of education gamification will help in improving the effectiveness of learning, increasing the interest of students to attend class, motivating them to perform better, and ensuring that they do not view education as a boring burden.

References

Arabian Gazette. (2013). Gamification coming to the Middle East.

Barlow, T., & Fleming, B. (2016). A science classroom that’s more than a game. The Journal of the Australian Science Teachers Association, 62(2), 31-37.

Brown, T. (2009). Change by design: How design thinking transforms organizations and inspires innovation. New York, NY: Harper Collins Business.

Bruder, P. (2015). Game on: Gamification in the classroom. Education Digest, 80(7), 56-60.

Caponetto, I., Earp, J., & Ott, M. (2014). Gamification and education: A literature review. Web.

Chang, W., & Wei, Y. (2016). Exploring engaging gamification mechanics in massive online open courses. Educational Technology & Society, 19(2), 177-203.

Collie, A., & Rine, J. (2009). Survey design: Getting the results you need.

Cranleigh Abu Dhabi Prep School. (2016). The Wire. Retrieved from Cranleigh Abu Dhabi Prep School.

Creswell, W. (2014). Reasearch design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Dakkak, A. (2014). How a Dubai venture hopes to gamify education and government.

Day-Black, C., Merrill, B., Konzelman, L., Williams, T., & Hart, N. (2015). Gamification: An innovative teaching-learning strategy for the digital nursing students in a community health nursing course. ABNF Journal, 26(4), 90-94.

Dent, B., & Goldberg, G. (1999). Challenging “resistance to change”. Dent, E.B., & Goldberg, S.G. (1999). Challenging “resistaThe Journal Of Applied Behavioral Science, 35(1), 25-41. Retrieved from Dent, E.B., & Goldberg, S.G. (1999). Challenging “resistance to change.”

Deterding, S. (2013). Gameful design for learning. T+D, 67 (7), 60-63. Web.

Dicheva, D., Dichev, C., Agre, G., & Angelova, G. (2015). Gamification in education: A systematic mapping study. Educational Technology & Society, 18(3), 75-88.

Fowler, J. (2008). Survey research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Gelo, O., Braakmann, D., & Benetka, G. (2008). Quantitative and qualitative research: Beyond the debate. Integrative Psychological & Behavioral Science, 42(3), 266-290.

Gilbert, S. (2016). Designing gamified systems: Meaningful play in interactive entertainment, marketing and education. New York, NY: Focal Press.

Grath, M., & Bayerlein, L. (2013). Engaging online students through the gamification of learning materials: The present and the future. 30th Ascilite Conference 2013 Proceedings (pp. 573-577). Sydney: Ascilite.

Harmon, J., & Copeland, A. (2016). Students’ perceptions of digital badges in a public library management course. Education for Information, 32(1), 87-100.

Huang, Y., & Soman, D. (2013). A practitioner’s guide to gamification of education. Toronto, Ontario: Rotman School of Management.

Jordan, P. (2012). Games and Learning: Gamification in formal educational settings. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii.

Khaddage, F., & Lattemann. (2016). Towards mobilizing mathematics via gamification and mobile applications. In H. Crompton, & J. Traxler, Towards mobilizing mathematics via gamification and mobile applications (pp. 266-277). New York, NY: Routledge.

Khaleej Times. (2016). UAE education goes digital. Web.

Kim, B. (2015a). Gamification in education and libraries. Library Technology Reports, 51(2), 20-28.

Kim, B. (2015b). The popularity of gamification in the mobile and social era. Library Technology Reports, 51(2), 5-9. Web.

Kim, B. (2015c). Designing gamification in the right way. Library Technology Reports, 51(2), 29-35.

Kopcha, J., Ding, L., Newmann, L., & Choi, I. (2016). Teaching technology integration to K-12 educators: A gamified approach. Teaching technology integration to K-12 eduTechTrends: Linking Research & Practice to Improve Learning, 60(1), 62-69.

Lee, J., & Hammer, J. (2011). Gamification in Education: What, How, Why Bother? Academic Exchange Quarterly, 15(2), 1-5.