Questions and rationale for patient complaining of urinary urgency, frequent urination, and Urethral burning persisting over the past 48 hours

Are you experiencing other symptoms like fever, back pain, or nausea?

This question should be asked to verify if there could be another underlying infection rather than the urinary tract infection.

Do you have any other medical problems? Are you on medication? Do you have any known allergies?

These questions should be asked in order to establish the patient’s medical history. According to Smeltzer et al. (2009), patients with medical conditions such as diabetes, those who are immuno-suppressed, chronically ill or those with indwelling catheters need to be identified and monitored in order to ensure that their urinary drainage systems and their renal functions are working properly.

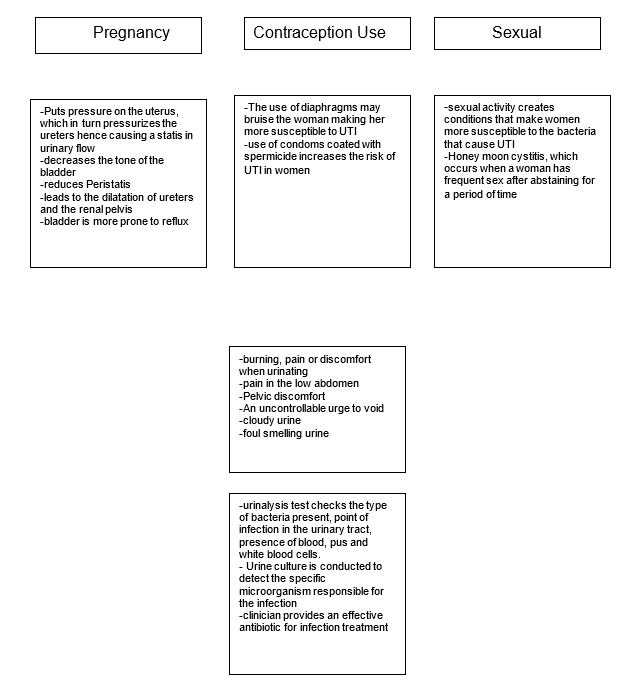

Have you been pregnant in the past? If so, did you have any complications or abnormalities while pregnant?

These questions should be asked in order to understand the obstetrics history of the patient. This is necessary in making a proper diagnosis.

How often do you have sex? Do you have multiple sexual partners? Do you use protection? Have you ever suffered from a sexually transmitted disease?

Although the patient’s personal history indicates that she is married, the GP cannot assume that she has one sexual partner. More so, establishing her sexual history will allow the GP to make a proper diagnosis of her condition.

Diagnostic tests indicated for the patient

With the patient’s body temperature, blood pressure, pulse rate, and breathing being within the normal range, the patient would need to have a dipstick test especially considering that she has had recurring UTIs over the past five years. According to Fenwick, Briggs and Hawke (2000), the dipstick test is an efficient, cheap, fast and reliable method of diagnosing symptomatic UTIs. Should she test positive for the bacteria, the general practitioner will then prescribe specific antibiotics meant to clear the infection. Smeltzer et al. (2009) also point out that the dipstick test is able to detect other abnormalities that the patient may have. Such include proteinuria and hematuria.

Laboratory test where her urine will be tested for bacteria causing UTI also need to be done. According to Fenwick, Briggs and Hawke (2000), patients with known allergies, and who have persistent symptoms must undergo the laboratory test. Two of the most common tests that can be done are the nitrite and esterase tests, which according to Smeltzer et al. (2009) indicate whether a patient has the suspected infection.

From the results, the clinician is then able to determine the specific antibiotics necessary for the patient’s treatment bearing in mind her allergy towards specific antibiotics. A urine culture may also be performed to ensure that the bacterium responsible for the infection is identified and the right antibiotics prescribed. Should the clinician suspect that the patient may have other urinary system problems, other tests including kidney ultrasound, kidney scan, intravenous pyelogram, CT scan on the abdomen and voiding cystourethrogram may be ordered.

Interpreting the urinalysis results

While the results indicate that the Urine is within normal pH levels, the 6.5 pH level indicates that its slightly acidic, which according to Simmerville, Maxted and Pahira(2005) could be a result of metabolic activities such as eating high protein diets or fruits high in acidic content. In patients with UTI, urine that registers alkaline pH levels indicates the existence of the urea-splitting organism (Simmerville, Maxted and Pahira, 2005).

The dark yellow color is evidence that the urine is concentrated. Further, the presence of nitrates and leukocytes is testimony that the urine is contaminated. The presence of 3 or 4 red blood cells per HPF is an indication that the patient has hematuria. The fact that the patient has a urinary specific gravity of 1.030 is a testament that she is well hydrated and that her kidneys’ concentration abilities are normal.

This rules out any probability that the patient may have impaired renal function, diabetes insipidus, aldosteronism or adrenal insufficiency. This interpretation is supported by Simmerville, Maxted and Pahira (2005), who state that USG “correlates with urine osmolality and gives important insight into the patient’s hydration status” (p. 1157). The presence of Escherichia coli bacteria at more than 104 Colony-forming units per ML suggests that the patient is suffering from UTI and hence the clinician should consider the right antibiotics for her condition.

Although the E. coli bacteria responsible for the patient’s UTI is sensitive to ampicillin, nitrofurantoin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ciprofloxacin, and cephalexin, the clinician can only prescribe nitrofurantoin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or ciprofloxacin, since the rest have penicillin content, which the patient is allergic to.

UTI and the genitourinary system

The genitourinary system is made of the urethra, ureters, bladder, and kidneys (Smeltzer et al., 2009). UTI mainly affects the bladder where patients complain of irritation, the urgency to void, frequency, suprapubic pain, and dysuria. The increased need to void leads to only a small amount of urine being voided at a time. According to Beers et al. (2006), an abnormality in mechanisms that ensure that there is a free flow of urine in the entire genitourinary system and that normal urine voiding occurs predisposes a person to UTI.

Causes of UTI include infection of the urinary tract, obstruction, malformation and indwelling catheters (Beers et al., 2006). Women are also more predisposed to UTI than their male counterparts due to the short female urethra, use of diaphragms as a contraceptive and menopause. Abnormalities in the urinary tract, hirschprung’s disease, urinary retention and constipation are also other identified predisposing factors. In addition, sexually active people, diabetes suffered and those who have suffered trauma around the urinary tract area are at an increased risk of UTI. Beers et al. (2006) observe that the highest percentage of UTIs are caused by the bacterium E-coli, while other bacteria like pseudomonas aeruginosa, Proteus mirabilis and klebsiella are also possible causes. In immuno-compromised patients, mycobacterium and fungi can also cause UTI.

The pathophysiology of UTI includes urgency to void, burning sensation during voiding, passing little volumes of urine frequently, pain on the patient’s lower back and lower abdomen, cloudy, strong smelling urine, fever and hematuria (Beers et al., 2006). The Clinical manifestations of UTI are based on bacteriuria obtained from the patient’s urine sample. Rapid tests such as the nitrate test using the dipstick are done to determine the amount of bacteriura in the urine sample. Still, quantitative urine cultures are done in cases where the rapid tests are not satisfactory. In cases where patients have recurrent UTIs, like is the case in this case study, a CT scan or an ultrasound can be done on the urinary tract.

Treatment of UTI mainly depends on the type of bacteria, the infection, the affected part of the urinary tract, and the recurrence of the infection. According to Beers et al. (2006), asymptomatic bacteriuria can be left untreated since it looses its virulence with time and becomes susceptible to the human plasma. Patients suffering from lower tract UTI can be treated with a dose of antibiotics. The antibiotics differ according to the causative bacteria. Patients with Upper UTI are also treated with antibiotics although alternative treatments such as quinolone and IV TMP-SMX can also be used (Beers et al., 2006). The treatment of recurring UTI, on the other hand depends on what the underlying etiology is.

Nursing Care Plan

Table 1 Care Plan 1.

Table 2 Care Plan 2.

Table 3 Care Plan 3.

References

Beers, M.H., Jones, T.V., Berkwits, M. et al. (2006). Kidney and Urinary Tract Disorders. The Merck Manuals of Geriatrics. Web.

Fenwick, E., Briggs, A., & Hawke, C. (2000). Management of urinary tract infection in general practice: a cost-effectiveness analysis. British Journal of General Practice. 50: 635-639.

Simmerville, J.A., Maxted, W.C.& Pahira, J. J. (2005). Urinalysis: a comprehensive review. American Family Physician Journal. 71(6):1153-1162.

Smeltzer, S., Bare, B., Hinkle, J. & Cheever, K. (2009). Brunner and Suddarth’s textbook of medical-surgical nursing. London: Lippincott Williams& Wilkins.