Factors affecting the process design

The manufacturing potential of a company depends largely on its flexibility in its production design line to ft its business goal (Cox Jnr, 1989). This idea was employed by Honda Car Manufacturing Company which in its bid to remain ahead in business chose to reduce the length of its line process but increased their offline process

There are a number of reasons that may cause drastic changes in a process design in the manufacturing industry. They include the nature of demand on the product; the degree of vertical integration, the level of automation in the process line, the quality level required by the customer and the degree of a contract entered with the customer.

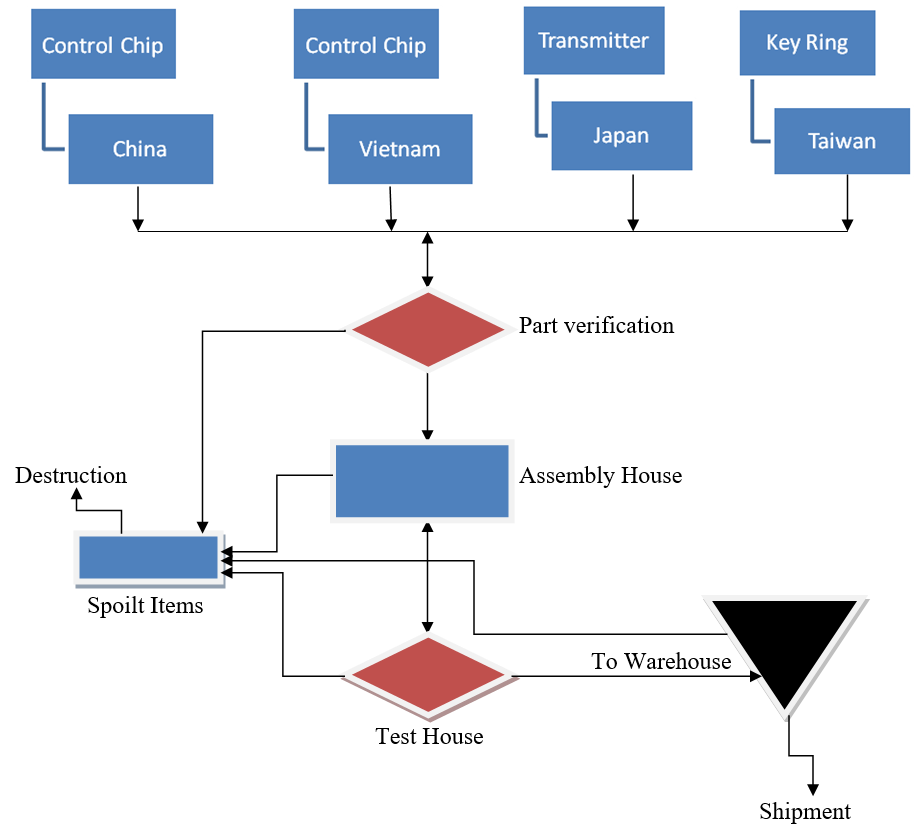

Scope of operations is a factor in which demands knowledge of how many tasks shall be done by the company and how much by the supplier. In our case most of the work is done by the suppliers who will do the actual design while the company only assembles the components.

The scale of operations is another factor considered. It is important in this case to know the products required at a particular time. For the company 835,000 fobs are required per year. This makes it cheaper to assemble pre-fabricated parts.

Other factors affecting the design process are the actual product cost and the time allowed for availing the product to the car manufacturer. This might involve a decision to select the particular process to include in the production line as Chase et al 2006 suggest.

Unit to Measure the Process Design

Dangelmaier et al, 2010 suggest that there are three main dimensions used in measuring a design process. These are the economic, the ecological and the social input and output. They also suggest that an improvement in any one of the above can lead to substantial improvement in the process without affecting other dimensions (also known as the Pareto improvement); or it may improve the process in one dimension while the other dimensions deteriorates.

In our case, we may consider the Pareto improvement as our measuring unit. In this case, an economic, ecological or social input or output will lead to the sustainability of the design process which can give us a basis for choosing whether a process design is worthwhile or not. In this case, the company has undertaken to distribute income without incurring cost to the material source countries while at the same time increasing their profitability. The company in choosing this approach of process design has shifted the procedural risks to the supplying companies which by the end of the day cushion it against losses due to long design processes. The ultimate purpose is to attract the suppliers with the incentive that leaves them with a net economical benefit while they offload the company of the burden of prototyping and other procedural delays that accompany prototype design processes. Considering the Pareto criterion (Mishan and Quah, 2007) in assessing this design;

If

K = initial capital outlay

B = subsequent benefits

TVr = Terminal value of the benefits

Then for this projects success TVr (B) > TVr (K)

This is to say that the terminal value of the benefits exceeds the terminal value of the initial capital outlay which as stated earlier is as a result of cost distribution to the suppliers away from the company liabilities. This is an assurance of continued profitability and improved customer service through timely delivery of the product on the market.

References

Brown, S. Blackmon, K. Cousins, P. 2001. Operations management: policy, practice and performance improvement. Butterworth-Heinemann. NJ.

Chase, R. B. Jacobs, F. R. and Aquilano, N.J. 2006. Operations Management for Competitive Advantage. McGraw-Hill. New York.

Cox Jr, T. 1989. Toward the Measurement of Manufacturing Flexibility. Production and Inventory Management Journal. Nova Scotia.

Dangelmaier, W. Blecken, A. Delius, R. Klöpfer, S. 2010. Advanced Manufacturing and Sustainable Logistics: 8th International Heinz Nixdorf Symposium, IHNS 2010, Paderborn, Germany, April 21-22, 2010, Proceedings. Springer. Germany.

Sugden, R. and Williams, A. H. 1978. The Principles of Practical Cost-Benefit Analysis. Oxford University Press,