Introduction

Flocking comes from the word “flock” described as a group of birds conducting flocking behavior in flight or when foraging. It may also refer to a herd of mammals. It was suggested that aggregating in flocks are varied and animals flock for specific purposes. Flocking also may be dangerous or disadvantageous particularly to socially subordinate birds which are bullied by more dominant birds.

However, Hutto (1988) suggested that birds may sacrifice feeding efficiency in a flock in order to gain other benefits. One principal advantage of flocking is the safety gained in numbers and another is increased efficiency in foraging. Likewise, Terborgh (2005) also noted the defense system against predators developed in flocking. This is particularly useful in closed habitats such as forests where predation is often by ambush.

The early warning provided by multiple eyes has led to the development of many mixed-species feeding flocks (Terborgh, 2005) that guard each other’s safety. The multi-species groups or flocks are most often composed of small numbers of many species. They may have increased numbers but are able to reduce potential competition for resources.

Flocking is has been considered a common demonstration of emergence and emergent behavior and it was first simulated on a computer in 1986 by Craig Reynolds with his simulation program Boids. In the program, simple agents move according to a set of basic rules that simulates a flock of birds, a school of fish, or even a swarm of flies.

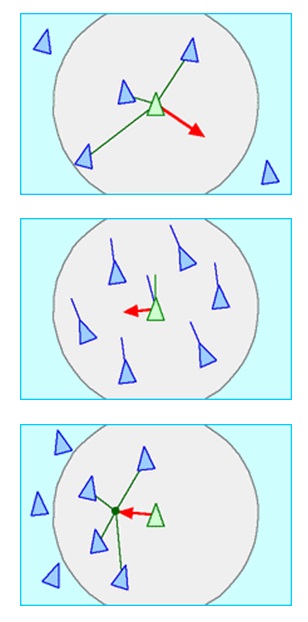

Reynolds (1995) pointed out the basic flocking is controlled by three simple rules:

- Separation – steer to avoid crowding local flockmates

- Alignment – steer towards the average heading of local flockmates

- Cohesion – steer to move toward the average position of local flockmates demonstrated in the following illustrations:

Based on these three simple rules, the flock is expected to move in a realistic way resulting in complex motion and interaction.

Main body

Since then, flocking has become s a common technology in screensavers and used in animation (Gabbai 2005) to generate crowds that move more realistically. Such program was used in the 1992 Batman Returns featuring a flock of penguins marching the streets of Gotham City, as well as in the 1994 Walt Disney animation The Lion King that had a wildebeest stampede.

Gabbai (2005) also suggested that flocking was considered from a more ambitious and practical perspective as a means to control the behavior of Unmanned Air Vehicles (Gabbai 2005).

In his own account, Craig Reynolds (1995) wrote that he made a computer model of coordinated animal motion such as bird flocks and fish schools based on three-dimensional computational geometry used in computer animation or computer-aided design as already presented above.

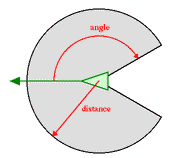

His explanation was that “each boid has direct access to the whole scene’s geometric description, but flocking requires that it reacts only to flockmates within a certain small neighborhood around itself. The neighborhood is characterized by a distance (measured from the center of the boid) and an angle, measured from the boid’s direction of flight. Flockmates outside this local neighborhood are ignored. The neighborhood could be considered a model of limited perception (as by fish in murky water) but it is probably more correct to think of it as defining the region in which flockmates influence a boids steering.”

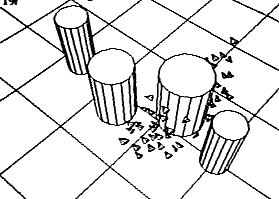

In addition, Reynolds (1995) narrated that a slightly more elaborate behavioral model was used in the early experiments with predictive obstacle avoidance and goal-seeking. In this process, the obstacle avoidance had the boids fly through simulated environments while dodging static objects. In use for computer animation, a low priority goal-seeking behavior caused the flock to follow a scripted path as illustrated below:

Reynolds (1995) added that an animated short featuring the boids model called “Stanley and Stella in: Breaking the Ice” was first shown at the Electronic Theater at SIGGRAPH ’87.

It was suggested that the Boids model interaction between simple behaviors of individuals produces complex yet organized group behavior (Reynolds, 1995). He described that “the component behaviors are inherently nonlinear, so mixing them gives the emergent group dynamics a chaotic aspect… the negative feedback provided by the behavioral controllers tends to keep the group dynamics ordered… result is life-like group behavior.”

One significant property of life-like behavior was pointed out as “unpredictability” over moderate time scales. “For example at one moment, the boids in the applet above might be flying primarily from left to right. It would be all but impossible to predict which direction they will be moving (say) five minutes later. At very short time scales the motion is quite predictable: one second from now a boid will be traveling in approximately the same direction.

This property is unique to complex systems and contrasts with both chaotic behavior (which has neither short nor long-term predictability) and ordered (static or periodic) behavior. This fits with Langton’s 1990 observation that life-like phenomena exist poised at the edge of chaos,” (Reynolds, 1995). Meanwhile, the edge of chaos may refer to a metaphor that some physical, biological, economic, and social systems operate in a region between order and complete randomness or chaos and that complexity is highly probable.

Interestingly, as early as 1974, Powell has pointed out that in groups of ten, individual starlings Sturnus vulgaris spend significantly less time in surveillance than did individuals in smaller groups. Likewise, they responded more quickly than single birds to a flying model hawk. It has been concluded that captive starlings in flocks reduce their individual surveillance efforts, but their combined efforts enable them to be more effective than single birds in the detection of predators.

The foraging behavior of flocks was observed in this experiment by placing single starlings with groups of tri-colored blackbirds Agelaius tricolor. It was established that the starlings reduced the time they devoted to surveillance at the same rate as when they were with other starlings.

Conclusion

There has been an initial positive indication that the flocking and boids models were useful in understanding animal behavior. This however provides several options such as those mentioned by Reynolds. Throughout the ages, men and non-rational animals have been analyzed for behavioral patterns from conscious, semi-conscious as well as unconscious states and have found that for every expectation are the equivalent opposite expectations that followed certain actions.

The same can be said with the boids and flocking models. It is, however, to be noted that when in flight and in the group as a flock, birds usually move in one direction for a reason that they have to fly south or fly north. As already mentioned elsewhere, habitation, weather, and survival have something to do with it. While the boids may, as Reynolds noted, be predictable, and are quite similar to flocking, it does not generally guarantee that certain patterns may be universal among rational and non-rational animals when it comes to behavior.

Reference

Gabbai, J. M. E. (2005), written at Manchester, Complexity and the Aerospace Industry: Understanding Emergence by Relating Structure to Performance using Multi-Agent Systems, University of Manchester Doctoral Thesis.

Hutto R (1988) “Foraging Behavior Patterns Suggest a Possible Cost Associated with Participation in Mixed-Species Bird Flocks” Oikos 51(1): 79-83.

Plowell, GVN (1974). “Experimental analysis of the social value of flocking by starlings (Sturnus vulgaris) in relation to predation and foraging.” Animal Behaviour 22 (2), Pages 501-505.

G.V.N. Powell. Terborgh J (2005) “Mixed flocks and polyspecific associations: Costs and benefits of mixed groups to birds and monkeys” American Journal of Primatology 21(2): 87 – 100.

Reynolds, Craig (1995). Boids. Web.