Introduction

Advertising and promotion campaigns are based on processes of memorizing and information retrieval, social learning, and personal attitudes. Many different types of information can be stored in memory as a result of exposure to a targeted ad and may exhibit different memory properties. A person’s motivation, ability, and opportunity to process will determine the intensity and direction of that process. For example, one motivational distinction for processing during ad exposure has been made between consumers who have ad evaluation goals and consumers who have brand evaluation goals. Consumers who view an ad with an ad aim, where they seek the entertainment value of an ad, may be more likely to direct their processing to execution characteristics of an ad. Two recent advertising campaigns were selected for analysis: the Guinness beer campaign and Fanta.

Considerations and Observations

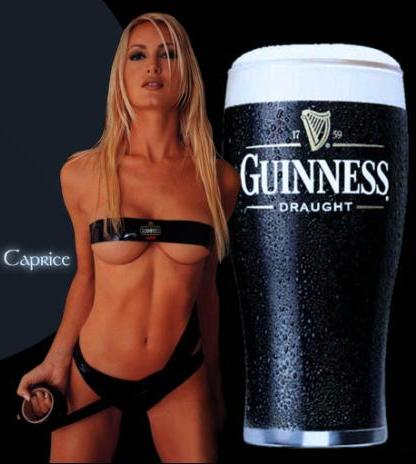

Both advertisements are connected with beverages and drinks important for all people on the earth (see Appendix 1,2,). People cannot exist without water and the everyday consumption of beverages. Beer is one of the most popular drinks since ancient times attracted people in all countries (Fill, 1999). Fanta and lemonades have shorter history but are extremely popular today. Both advertisements are based on decoding ad encoding information. That is, a person may deeply think about, or be emotionally affected by, an ad but maybe focusing that attention on some aspect of the ad not directly related to the brand claims, such as the source or spokesperson of the ad (high-intensity and ad-directed processing). Consumers who view an ad with a brand evaluation goal, where they seek information about the advertised brand, however, may be more likely to direct their processing towards product claims, although they may also critically evaluate the ad execution itself. That is, a person may carefully consider the claims made about a brand while processing an ad, rendering belief judgments as to its believability, and forming or updating an overall brand attitude (high-intensity and brand-directed processing). Besides motivation, ability considerations can also affect processing direction (Solomon et al 2005).

Both ads use visual stimuli as the min strategy to reach the potential consumer. Guinness’s ad uses sex and sex appeal to motivate the adult audience and create a unique image of its product. This ad is based on the unique image of a blonde girl compared with the best Guinness product. In contrast to this ad, Fanta uses colours and backgrounds to influence consumers’ decisions to purchase (Hollensen, 2007). Using the VIBE concept, it is possible to say that the perception of these ads is unique to each individual. Evidently, consumers low in knowledge lacked the ability to process the brand claim information in the ad and directed their processing elsewhere. Finally, as may often be the case, a person has almost no motivation or ability to process the ad and barely attends to either the brand claims or execution information (low-intensity processing) (de Mooij, 2003). A priority in the study of memory factors in advertising is an understanding of the accessibility of different elements of the ad memory trace. In a general sense, accessibility of the ad memory trace will depend on the organization of memory and the retrieval cues that are evident. it is possible to assume that the aim of the Guinness ad is to link satisfaction and desire with unique qualities of a product able to meet these needs. Fanta’s ad suggests that a person’s evaluative responses to information are often assumed to be more durable and accessible in memory than the actual information itself (Solomon et al 2005).

In both cases, consumers’ motivation to purchase a product is driven by a desire to try something new which meets his/her personal values. package or product appearance for each brand presents a combination of “new” visual or verbal information to which the consumer has not been exposed outside the store and “old” visual or verbal information, which either reinforces or suggests previously encountered information (Kotabe and Helsen 2006). Even if consumers store communication effects from ad exposure in memory, there is no guarantee that anything from that ad memory trace will play a role during brand evaluations. For example, consumers may have little motivation to retrieve any information such that low retrieval intensity is forthcoming. They may use stored decision rules based only on information physically present at the point of purchase (e.g., always buy the same brand or the least expensive brand in a product category), ignoring or overlooking any communication effects available in memory (de Mooij, 2003).

Fanta’s and Guinness ads show that to the extent that these pieces of information appear in the ad, they can then function as cues for communication effects stored in the ad memory trace. The effectiveness of these cues will depend on the strength of their links to the ad representation and ad response elements in the ad memory trace. In the case of Guinness, weak links from the brand name to the ad memory trace may occur because of the nature of the ad itself (either its structure or content), the environment surrounding the ad (e.g., the type and extent of competitive advertising), and the person’s motivation and ability to process the ad at encoding (Solomon et al 2005).

Summary

Guinness and Fanta use unique images and symbols to motivate potential consumers and influence their decision to purchase. Both ads are based on cognitive learning principles that appeal to internal stimuli. Marketers use stimuli in order to increase attention and influence the sensory-perception process. Meaningful and bright images, visual messages, and appeals persuade buyers to try this product. Generally, factors affecting retrieval motivation are related to characteristics of the person (e.g., goals). Consumers will be more motivated to retrieve ad information when they think that it will help them in their brand evaluations. The ability to retrieve depends on the organization of information in memory and the retrieval cues that are present.

Bibliography

Fill, C. 1999. Marketing Communication: Contexts, Contents, and Strategies 2 edn. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Hollensen, S. 2007, Global Marketing: A Decision-Oriented Approach. Financial Times/ Prentice Hall; 4 edition.

Kotabe, M., Helsen, K. 2006, Global Marketing Management. Wiley.

de Mooij, M. 2003, Consumer Behavior and Culture. Sage Publications, Inc.

Solomon, M. R., Bamossy, G. Askegaard. A. 2006, Consumer Behaviour: A European Perspective. Financial Times/ Prentice Hall.