Introduction to Hans Vogel’s Diary

Diaries provide some of the most personal and heartbreaking recollections of the Holocaust. They capture the feelings of suffering, fear, and, occasionally, hope of people in great danger. The selected artifact is Hans Vogel’s diary, which recounts the experiences of an adolescent and his family (“The Diary”).

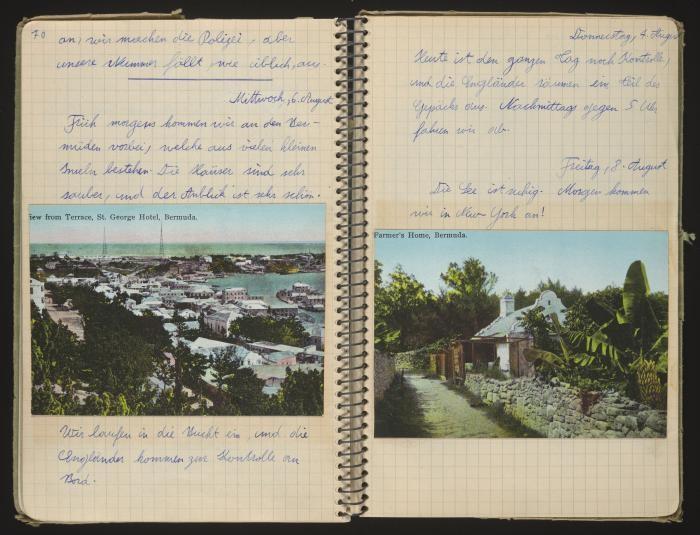

Hans Vogel made his final journal note on August 9, 1941, describing that his family was sailing and saw the Statue of Liberty (“The Diary”). According to the youngster, they were the first to exit and were welcomed by their friends and acquaintances. Thus, the Vogel family arrived in the United States after a long journey.

Hans escaped Nazi Germany with his relatives in 1936, staying in Paris until the German invasion of France in 1940. The family escaped into unoccupied France near the Spanish border before German soldiers arrived in Paris. On July 24, 1940, Hans, a 13-year-old, began his journal there (“The Diary”). The paper will describe the story in the voice of the diary to discuss the feelings and events.

From the Diary’s Point of View

I am a diary, and my owner’s name is Hans Vogel. My pages were empty; I was ready to be filled with thoughts, feelings, and experiences. It has been a couple of days since I was put in the hands of a young boy around 13. He seemed happy to receive me as a gift, but I could tell he was also scared. There was a sadness in the boy’s eyes that I could not understand before he started telling me. Today is July 24, 1940, and Hans began to write describing the journey to the United States (“Hans Vogel’s Diary”). I can feel the emotions behind his words, the fear and hope.

The boy talks about the never-ending wait for visas and travel documents. The youngster sometimes writes about his interests, which include gardening, swimming, and movies (“The Diary”). Hans stresses that the family obtained US visas and proceeded to Portugal through Spain to catch a ship.

As a journalist, I believe the Vogels were lucky since the US immigration system limited the number of persons who could enter each year. Nonetheless, the family waited over a month for their ship, Nyassa, to depart after arriving in Portugal (“The Diary”). Sometimes he writes daily, and sometimes I do not see him for days. I can feel his despair growing, and it breaks my heart.

As a Diary, I saw the boy’s relatives, and they became my family. My owner was born on December 3, 1926, in Cologne, Germany (“Hans Vogel’s Diary”). In 1936, the family fled Germany and settled in Paris, and stayed there until the outbreak of World War II (“Hans Vogel’s Diary”). Hans’ father, Simon, was detained as an enemy alien by the French at Lisieux and, afterward, Gurs.

When German soldiers arrived in Paris, the Vogel family escaped south. Following Simon’s release from Gurs, the family rejoined and lived at Oloron-Sainte-Marie, near the Spanish border in France’s unoccupied zone (“Hans Vogel’s Diary”). Hence, they stayed there from June 1940 until April 1941, when they were granted permission to immigrate by the US Consulate.

After arriving in the US, Hans forgot about me, and I was worried that something terrible had happened. Tragically, Hans died from an illness in 1943, less than two years after arriving (“Hans Vogel’s Diary”). I can feel the pain and sorrow of the boy’s absence because a part of me is missing. I am silent, but I want to interact and tell the story of my owner to everyone and show the photographs, postcards, and hand-drawn maps I keep on my pages. Hans’ family preserved me, and I saw how they read me with tears.

It is 1945, World War II is over, and I am happy I was saved to share Hans’ story. Among the millions of children tortured and oppressed by the Nazis and their Axis allies, a tiny minority kept diaries and notebooks that have survived (“Children’s Diaries During the Holocaust”). My owner wrote about his experiences, confessed his feelings, and pondered his difficulties throughout these horrible years.

I hope that one day people will know my story, but for now, Han’s relatives are my only readers. Many years after the tragic experiences, Hans’s sister-in-law donated the diary to the Museum in 2013. Approximately six million European Jews were murdered in the Holocaust, and children comprised around 1.5 million victims (“Children’s Diaries During the Holocaust”). I discovered that I am a refugee diary and addressed the problem of displacement; my owner had given up the comforts of home to seek protection among strangers in other countries. I hope that people never forget the lessons of the Holocaust.

Conclusion

Han Vogel’s diary was saved and now serves as a symbol of the Holocaust. Child diarists who immigrated legally, such as Hans, noted the enormous bureaucratic obstacles in finding refuge and getting the appropriate visas and paperwork (“Children’s Diaries During the Holocaust”). Diarists who escaped illegally recall the dangerous trek across treacherous terrain and the continuous anxiety of being arrested. Refugee diaries reveal the terrible and perplexing loss of home, language, and culture, and the struggle to adjust to life in a strange and frequently alienating world.

Works Cited

“Children’s Diaries During the Holocaust.” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Web.

“Hans Vogel’s Diary.” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Web.

“The Diary.” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Web.