Hecksher-Ohlin theory is a theory of international trade first developed by two Economists from Sweden called Eli Hecksher and Bertil Ohlin. The main driver to its development was the difficulty encountered by Economists in trying to explain the trend of international trade.

Eli Hecksher (1879-1952) was mainly interested in economic history but in 1919, he developed some fundamentals of the factor endowment theory of international trade. He was known for his book “Mercantilist” (introduction part of Hecksher Ohlin Trade Model n.d).

Bertil Ohlin (1899-1979), Hecksher’s student greatly built the factor endowment theory. He was also a political figure during the Second World War as the Swedish Trade minister and was awarded a Nobel Prize for his contribution to international trade studies.

The theory is modeled on a situation involving 2 countries, 2 commodities and 2 factors of production namely labor and capital. It is thus also called the 2*2*2 model (Robert 1988 p3).

It is based on several assumptions which may appear somewhat unrealistic in terms of their applications in the real world but even so, the results explained in the theory are largely applicable.

The theory assumes that there exist only two countries trading between each other in two products only. It also assumes that there exist only two factors of production namely labor and capital and that only these two factors are used in the production of the two products. Of crucial importance is the assumption that one of the commodities is labor-intensive while the other is capital-intensive. Being labor-intensive implies that the production process utilizes more units of labor than capital in producing a unit of output. Being capital intensive implies that the production process applied in the production of the good utilizes more units of labor per unit of output than it uses capital (Robert 1988 p4).

It also assumes that no barriers exist in trading with the goods between the two markets. This implies that respective governments in the two countries do not interfere with the free movement of goods between the two countries. No tariffs, quotas, foreign exchange controls, or any other export or import restraints are imposed on trade. This is not true in the real world (Hecksher Ohlin Trade Model 3.

Interestingly, the theory assumes that no transportation costs are incurred in moving the goods from one country to the other. The main reason for the assumption is to ensure that no additional costs are in play which may be large enough to reverse the arguments of the theory. The assumption serves to ensure no impediments hinder trade between the two countries. It may be unrealistic but it is true that transportation costs do not reverse trade patterns but rather reduce the volume of trade (Robert 1988 p6).

The factors of production (labor and capital) are freely able to move from one part of a country to another but not across borders. Products can freely move across the borders but factors of production cannot. The Domestic Factor Mobility (DFM) ensures that labor can freely move from areas of low wage rates to areas of high wage rate while capital is able to freely move from areas of high low-interest rates to areas of high-interest rates. The net effect of these movements is the stabilization of the factor prices in each country (Robert 1988 p10).

Illustration

In the United States workers should be able to move from states with low wage rates to those with higher wage rates while capital easily flows from states with low returns to those with higher returns. The net effect is a country whose wage rate is uniform in all states and the interest rates are also equal in all states.

The theory assumes perfect competition in both factor and product markets. This guarantees a situation of optimal utilization of the factors of production and eliminates hindrances to the movement of wages. It also ensures that prices are determined in a competitive environment with no monopolistic or oligopolistic practices that tend to maintain higher prices in order to obtain abnormal profits. Perfect competition implies multiplicity in buyers and sellers hence everyone is a price (Robert 1988 p10).

Still, it assumes that all factors of production available in each country are fully utilized in production. The production functions follow the production possibility frontier for the economies.

This means that both countries produce both goods. No one country exclusively produces one good leaving out the other regardless of the endowment in capital or labor. The difference is in the level of production of each good.

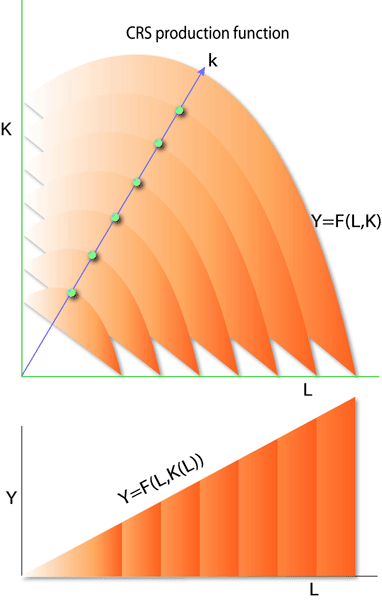

This means that the production functions in both countries exhibit Constant returns to Scale. In a case where there is a proportional change in the uses of capital and labor, it results in an equivalent change output. A rise in capital and labor by the same percentage results in an increase in the level of output by the same proportion (Bagicha 1962 p149).

Illustration:

- y-level of output, K-capital, L-Labour

- y is a function of capital and labor hence

- y=f (K/L).

In case of constant returns to scale, doubling the use of capital and labor doubles the level of output hence 2y= (2K/2L)

Graphically:

Output increases at the same rate as proportionate increases in inputs. The rate of increase corresponds to the increase in both capital and labor as shown in the lower Graph

The production processes in the production of the two goods are the same in both countries. No country is left behind in adopting new technology. This assumption serves to ensure constant returns to scale because different technologies can result in different levels of output even when equal amounts of input are applied.

Factor Intensity Reversal (FIR) is a case whereby the ordering of factor intensities for the two products differs due to changes in factor prices. A rise in wage rate can effectively change the factor intensity of a commodity from being capital-intensive to being labor-intensive and vice versa. This is assumed not to be the case to ensure consistency in applying the theory (David 1966 p89).

As has been explained earlier, the relative abundance of labor in one country makes it cheaper than in the other country. This implies that the country more endowed in labor will produce labor-intensive goods cheaply as compared to the other. Also, the relative abundance of capital in the capital-rich country enables it to produce capital-intensive goods cheaply (Bagicha 1962 p145).

Before the introduction of free trade, the price of the labor-intensive commodity is lower in the country more endowed with labor due to the low wage rates. Also, the price of the capital-intensive good is lower in the country more endowed with capital as the interest rates are lower.

On introducing free trade, the rush is on by profit-oriented businesses. The country richly endowed in capital exports capital-intensive goods to the labor-rich country. On the other hand, the labor-rich country exports labor-intensive goods to the capital-rich country. The aim is to take advantage of the higher prices across the border by utilizing the comparative advantage in home country. Holding the above assumptions as true, the result is that each commodity’s price equalizes in both countries due to competition. The price of the capital-intensive good both in the capital-rich country and the labor-rich country equalizes. On the other hand the price of the labor-intensive good in both countries also equalizes (Hecksher Ohlin Trade Model 6).

It is important to note the relative factor prices before free trade. In a labor-rich country, the cost of capital relative to labor is very high due to scarcity. However in the capital-rich country, the cost of labor relative to that of capital is high (Robert 1988 p10).

The adjustments in prices described above will result in adjustments in the factor relative factor prices. The relative price of labor in the labor-rich country will be rising to match that of the capital-rich country which is gradually falling. This implies that the level of wages rate to that of interest rates in the labor-rich country will equal the wage rate relative to the interest rate in the capital-rich country. Also, the relative price of capital in the capital-rich country will be rising to match that of the labor-rich country which is gradually falling.

The implication is that the introduction of free trade between countries equalizes the prices of output commodities and consequently, the prices of factor inputs are also equalized.

International trade today has exhibited the characteristics described above. The signing of the North American Free Trade Association (NAFTA) by the US, Canada and Mexico in 1992 prompted a gradual fall in wages for unskilled workers in the US as they gradually rose in Mexico. This was due to the easier movement of unskilled workers from Mexico to the US (Davis, Donald & David 2001 pp 1441).

Still the trend can be observed in the economic relationship between China and the western developed world. The western nations are rich in capital but labor is scarce. This means that capital is cheap as compared to labor. China and other Asian countries are rich in labor but capital is scarce. This has prompted mass flows of capital from the US and Europe while workers move from Asia to the US. Investors are moving to China where wages are estimated to be 75% less than those in the west as their capital invested gives higher returns. Workers on the other hand are moving from china to the US due to the high wage rates there (Davis, Donald & David E. Weinstein. 2001 p.1442).

An example is IBM, a huge computer producer which shifted production from the US to china taking advantage of low wages.

The European Union has similar characteristics. Countries to the East such as Hungary, Poland and the Czech Republic have lower wage rates than those to the west. Their inclusion in the European Union has evidently resulted in the gradual rise in the wage rate in their economies. During the year 2000 to 2003 wage rates in Hungary rose by 20% while in the Czech Republic it also increased by 15% (Davis, Donald & David E. Weinstein. 2001 pp 1445).

In the long run, it is expected that the gap between the wage rates in the east as compared to the west will be largely reduced as workers migrate to western countries and as capital flows toward the East. The interest rate differential will also close.

In the real world the theory looks faulty mainly due to the assumptions. Indeed, transport costs are very significant to international trade and the assumption nullifying them is not realistic. Also, the theory can only be sensibly applied in analyzing export markets for industries that can be identified as capital or labor-intensive such as manufacturing and agriculture.

Nevertheless, the theory is very applicable in analyzing trade as observed above. The assumptions do not hold but the driving forces behind trade among nations can be pointed to the endowment differences and the mobility of factors of production.

Reference

Appleyard, F., Cobb, S., 2006, International Economics (5th ed.). McGraw-Hill Irwin.

Bagicha, S., 1962.The Homohypallagic Production Function, Factor-Intensity Reversals, and the Hecksher-Ohlin Theorem. The Journal of Political Economy, [Online] 70(2) pp. 138-156. Web.

David, S., 1966. Factor-Intensity Reversals in International Comparison of Factor Costs and Factor Use. The Journal of Political Economy, [online] 74(1), pp. 77-80. Web.

Davis, D., Donald, R., and David E. Weinstein. 2001. An Account of Global Factor Trade. American Economic Review, Vol. 91, pp. 1423-1453.

Robert W., 1988. Hecksher-Olin Theory and Non-Competitive Markets. NBER, [Online]. 2009. Web.

The Hecksher-Ohlin Trade Model [Online] 2009. Web.