Introduction

Fossil records reveal a wide study of the evolution of the horse. Horses belong to the modern-day members of Equidae. The horse belongs to the same class as zebras, asses, and donkeys. These members have long legs and run fast. These characteristics are believed to be adaptations for the horse to live on open grasslands. This species belongs to the genus Equus. It is the last alive offspring of a family known to have had more than 30 genera tracing back to the Eocene period 50 Million years ago. This paper examines the evolutionary trend of the horse.

The First Horse

The first horse was miniature, short-legged, and had broad feet. Figure 1.0 shows the Hyracotherium sandrae. Its shape was different from the modern day horse (Mihlbachler et al. 1178).

Change in Size

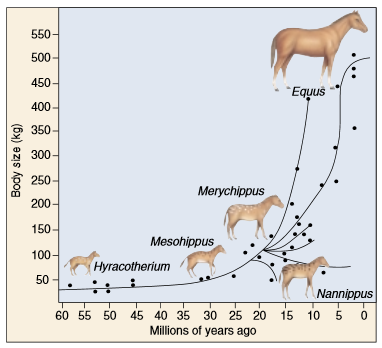

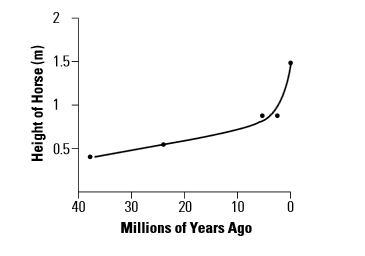

These species lived in wooden habitats where they browsed on leaves and herbs. Mihlbachler et al. say that these species had unique ways of escaping predators including ducking through openings in the forests and running fast (1180). The evolutionary path of the horse has seen various trait changes through time. The most notable change is the increase in body size as shown in figure 1.2.

Fossil records indicate that for the first 30 million years, the horse was the size of a dog (Holmes, VandeBerg, and Cox 291). Then, little by little, it increased gradually through time as shown in figure 1.2.

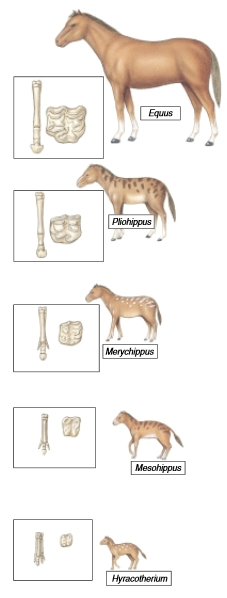

Toe Reduction

However, after that period, some different lineages have continually showed rapid and substantial changes in size (Secord et al. 959). As a result, the equid evolutionary tree shows a decreasing trend in some branches as exhibited in figure 1.3.

This change involved mainly toe reduction (Holmes, VandeBerg, and Cox 291). Its feet have a single toe. Tough bony hooves encase the toes. This adaptation helps the horse to run fast through long distance. Conversely, the Hyracotherium had four toes on its front feet and three on its hind feet, which were enclosed in fleshy pads rather than hooves (Shoemaker and Clauset 215). In addition, early fossils reveal transition through time (Secord et al 959). It involved lengthening of the central toe coupled with growth of the bony hoof. At the same time, its other toes reduced and then finally lost (Shoemaker and Clauset 215). Researchers argue that the evolution trends of the horse present simultaneous changes that are different from the branches of its evolutionary tree (Secord et al. 959). Another important evolution change was the lengthening of the skeletal structure of its limbs. Shoemaker and Clauset argue that this adaptation enables the horse to run fast for long distances (219).

Tooth size and shape

Another significant evolution change involved the length of teeth of the Hyracotherium. Fossil records show that the length has increased markedly over- time from a simple to a complex structure. The back teeth have patterned ridges (Orlando et al. 76). In addition, Holmes, VandeBerg, and Cox assert that the evolutionary changes in teeth were necessary to help to horse chew tough vegetation (291). Grass has the tendency of wearing out weak teeth.

At the same time, the horse’s skull changed in shape. Researchers argue that the change of its skull length enables the horse to endure the stresses caused by continuous chewing (Secord et al. 959). Contrary to early studies, the change in body size of the horse was not persistent through the millions of years (Mihlbachler et al. 1181). Fossils records show that some members grew in unrelated family lines. Orlando et al. believe that most of these changes were adaptations of the horse to survive in its habitat (74). These adaptations were important for the horse to run through long distances at high-speed especially when evading predators (Holmes, VandeBerg, and Cox 291). The manifold toes and tiny limbs helped the horse to evade predators by ducking through forest thickets.

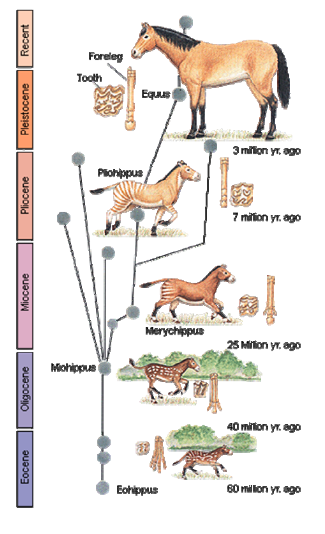

The Evolutionary Tree of the Horse Family

Evolutionary change through millions of years does not occur uniformly contrary to numerous early studies (Weinstock et al. 1375). Recent studies reveal that these changes are neither constant nor uniform through time (Orlando et al. 75). In fact, evolution changes vary widely. Some exhibit long periods of miniature change and others portray periods of pronounced change (Shoemaker and Clauset 215). Weinstock et al. assert that there were concurrent changes in different families of the horse evolutionary tree (1379). The following figure shows the evolutionary tree for the horse family.

Conclusion

Evolution of the horse has been widely studied for many years. Numerous points are worth noting regarding the evolution of the horse. Enough fossils have demonstrated that evolution does not occur in a straight line. Moreover, evolution does not occur following a particular goal. Instead, it is analogous to a branching bush without a specific predetermined goal. Researchers believe that many horse species lived simultaneously yet exhibited varying characteristics such as different numbers of toes, the size of teeth, and body. They adapted to different diets. Moreover, the evolutionary trend of the horse family was not consistent. For instance, as the number of toes reduced, the size of the cheeks increased. Concurrently, the face lengthened. The horse presents a better evidence of evolution than other animals and even humans.

Works Cited

Holmes, Roger, John VandeBerg and Laura Cox. “Vertebrate Endothelial Lipase: Comparative Studies of an Ancient Gene and Protein in Vertebrate Evolution.” Genetica 3.1 (2011): 291. Print.

Mihlbachler, Matthew, Florent Rivals, Nikos Solounias and Gina Semprebon. “Dietary change and evolution of horses in North America.” Science 331.6021 (2011): 1178-1181. Print.

Orlando, Ludovic, Aurélien Ginolhac, Guojie Zhang, Duane Froese, Anders Albrechtsen, Mathias Stiller and Mikkel Schubert. “Recalibrating Equus evolution using the genome sequence of an early Middle Pleistocene horse.” Nature 499.7456 (2013): 74-78. Print.

Secord, Ross, Jonathan Bloch, Stephen Chester, Doug Boyer, Aaron Wood, Scott Wing, Mary Kraus, Francesca McInerney and John Krigbaum. “Evolution of the Earliest Horses Driven By Climate Change in the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum.” Science 6071.1 (2012): 959. Print.

Shoemaker, Lauren and Aaron Clauset. “Body Mass Evolution and Diversification Within Horses (Family Equidae).” Ecology Letters 17.2 (2014): 211-220. Print.

Weinstock, Jaco, Eske Willerslev, Andrei Sher, Wenfei Tong, Simon Ho, Dan Rubenstein, John Storer, James Burns, Larry Martin and Claudio Bravi. “Evolution, Systematics, and Phylogeography Of Pleistocene Horses In The New World: A Molecular Perspective.” Plos Biology 3.8 (2005): 1373-1379. Print.