Introduction

Our world is growing rapidly. Growth which is evident on every country’s way of living. Most countries around the globe has developed and improved from the day they were discovered. But this development does not come easily; it has to be worked hard on. At the same time, this does not come in unison – meaning there are countries that have achieved development ahead of the others. That is why concepts like the “Third World Countries”, the “Second World Countries”, the “First World Countries” and now the “Developing Countries” has been coined.

The Third World is the underdeveloped world – agrarian, rural and poor. Countries belonging to the third world are marked by a number of common traits – quite distorted and have highly dependent economies devoted to producing primary products for the developed world and to provide markets for their finished goods. The Second World was the Communist world led by the USSR. With the demise of the USSR and the communist block, Second World does no longer exist. The First World, on the other hand, is the developed world. Countries like US, Canada, Western Europe, Japan, Australia and New Zealand has long been a part of this world.

However, because most countries felt and realized that they need to grow and move forward, a new term has been made up – the “Developing country”. The term developing country refers to the non-industrialized poor country that is seeking to develop its resources through industrialization.

The idea of a developing country is something new causing for certain queries to arise. Questions like “how do you describe a developing country?” or “can you classify a country if it is a developing one or not?”, “what are other things and concepts we need to know in order to familiarize ourselves with this developing country?” and even “are developing countries really in a state of poverty or is it just imagined?”.

This research study is made in the hope that it will find pertinent answers to questions stated above, as this is timely and can be very useful in helping our and the other nations grow for the betterment of its people and its country as a whole.

Social and Governmental Aspects of the Developing Countries

Comparing, contrasting and reviewing all the factors contributing to the growth and advancement of a certain country will lead us to objectively analyze significant data and information on how can one country be successful enough in its struggle to be one among the highly developed countries. Various factors such as the intervening agencies of the government will be regarded as one essential tool on this part of the study.

Economy

A developing country’s economic situation can be described as an economy that is lacking in strong amounts of industrialization, infrastructure, and sophisticated technology, but are beginning to build these capabilities. Countries in the process of change directed toward economic growth, that is, an increase in production, per capita consumption, and income. The process of economic growth involves better utilization of natural and human resources, which results in a change in the social, political, and economic structures.

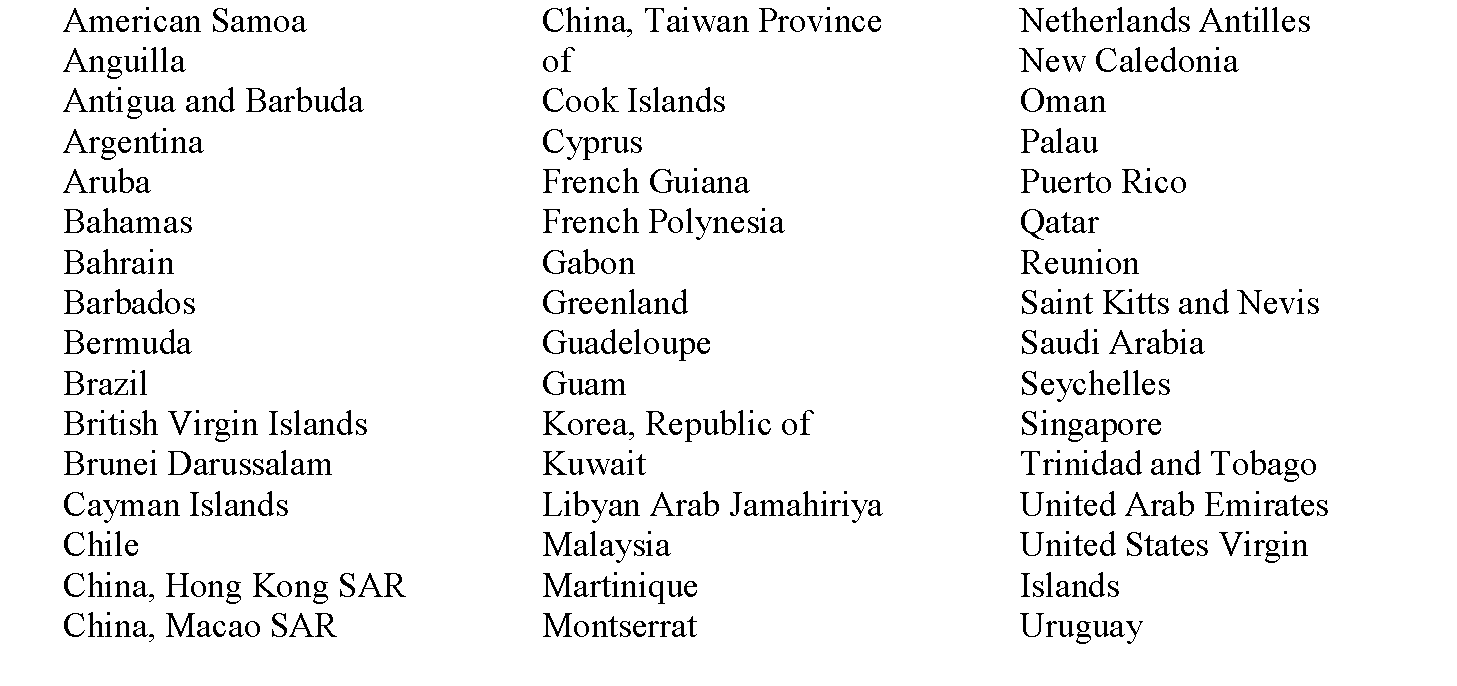

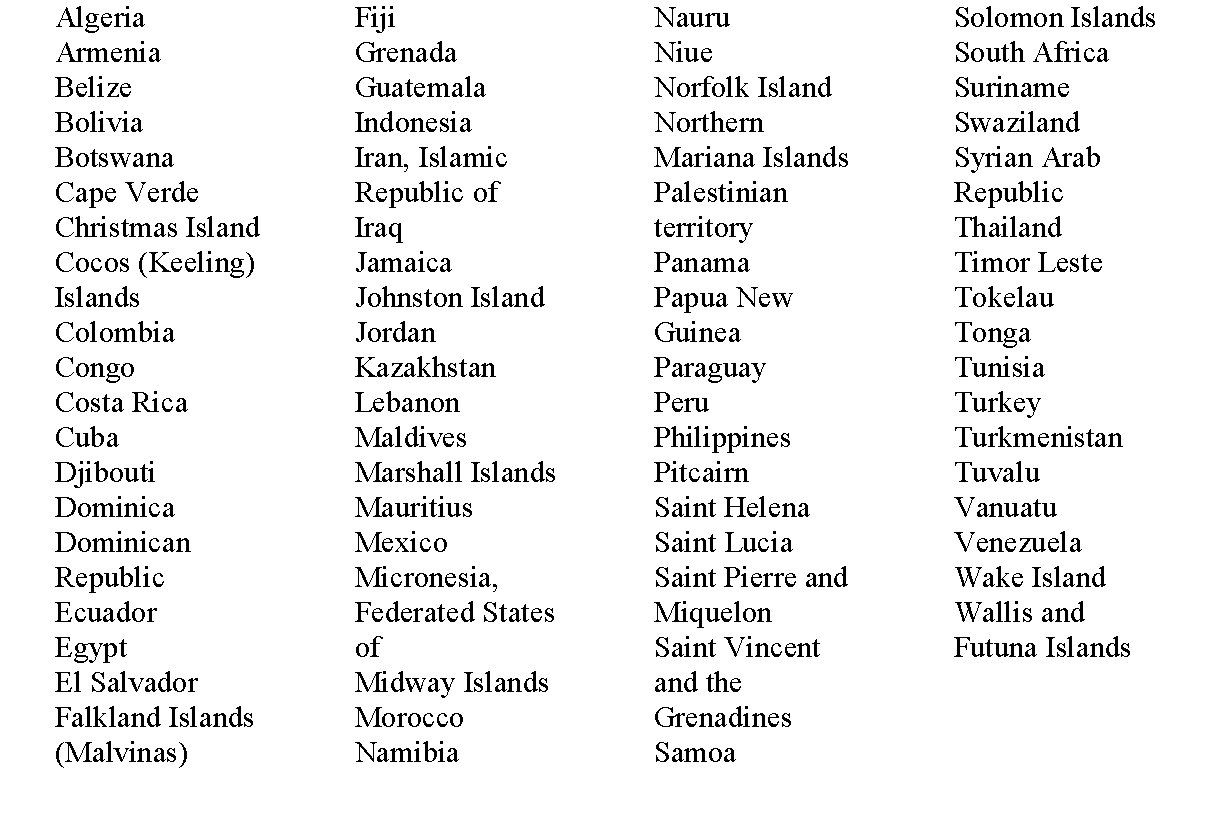

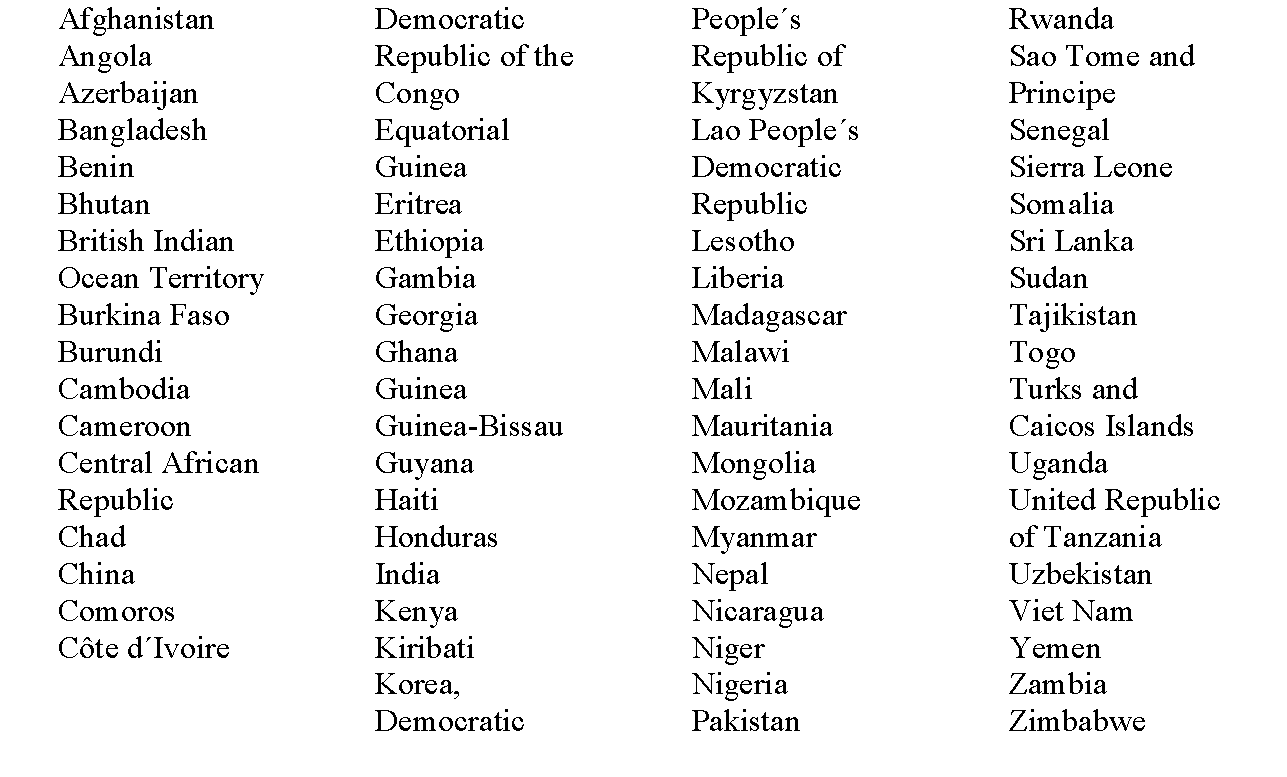

And speaking of per capita income, let us take a closer look of the GDP of the countries considered to be developing. This study was taken last 1995:

1995 Per Capita GDP above US$ 4,000: 46

1995 per capita GDP between US$ 800 and US$ 4,000: 71

1995 per capita GDP below US$ 800: 65

As we can see from this survey, there are lots of countries that is said to be on the process of developing. Even the Per Capita GDP is not evenly equivalent from each of the country, there are still high, middle and low income earners. This study is inviting another good question such as what are the sources of income of those developing countries considered to be high-income earners. It is safe to assume that by analyzing those countries with the high-income bracket, most of them are large countries and has enough “unique” resources. Like for example, Brunei, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, all of us are aware that these countries are very rich in oil making other countries totally dependent on their supplies. Hence, this oil source is providing enough money on their GDP.

Health

In any developing country, health is another one important aspect of the populations’ life that should not be taken for granted. Before, malnutrition is highly prevalent among developing countries, and this can be attributed to the fact that there is lack of funding or government attention on health and health education. But the results of the study made on the year 2000 revealed that between 1970 and 1995, the number of malnourished children declined by 37 million, from 204 million to 167 million, while the prevalence of malnutrition in the developing world as a whole fell from 46.5 percent to 31 percent, about 15 percentage points in all. Progress in reducing malnutrition has varied greatly from one region to another. The prevalence of malnutrition has declined the fastest in South Asia (by 23 percentage points) and slowest in Sub-Saharan Africa (4 percentage points). The number of malnourished children has declined most sharply in East Asia (from 78 to 38 million). The situation is particularly troubling in Sub-Saharan Africa where the number of malnourished children has increased by 70 percent. Since 1970, the prevalence has decreased in 35 developing countries, held steady in 15, and increased in 12, with most of the countries with increases in Sub-Saharan Africa (Smith and Lawrence, 2000).

Although child malnutrition is found to have significantly changes, maternal health is still a continuing problem. Bad health services contribute significantly to maternal deaths. For example, a study of 152 maternal deaths in Dakar, Senegal, showed that the following major risk factors were associated with health system failures: medical equipment breakdown, late referral, lack of antenatal care and, most importantly, non-availability of health personnel at the time of admission (Garenne et al., 1997). Indeed the lack of a skilled attendant at the time of childbirth is the most serious risk factor for maternal death and yet the percentage of births attended by a trained person can be as low as 5% in some developing countries. Similarly family planning services can be poor and erratic, contributing to the lack of interest among potential clients (Casonde, 2003).

Population

In the year that Emperor Augustus Caesar died, AD: 14, the population of the world was 260 million (Belloch, 1886). By the year 1815 it had reached 1 billion and is believed to have increased rapidly thereafter to 2 billion in 1927, 3 billion in 1960, 4 billion in 1976 and 5 billion in 1987. Now, it is reaching nearly 6 billion. The notable feature is that, of the 2.8 billion people added to the world’s population between 1950 and 1990, 87% came from the developing countries. Moreover, the number of inhabitants in developing countries more than doubled, while the number in developed countries grew by 45%. By 1990, over three-quarters of the world’s population were living in the developing countries (UN, 1991).

Of course, the use of contraceptives is a great factor to this continuously increasing population. Contraceptive prevalence surveys ten years ago showed that, worldwide, about 325 million out of nearly 800 million married couples of reproductive age were estimated to use an effective modern form of contraception. Of these, about 135 million relied on voluntary male or female sterilization; 70 million used the intrauterine device (51 million in China alone) and 55 million used oral contraceptives. But, although 40-50% of couples now use contraceptives the percentage in developing countries is low, in some countries as slow as 5%. Developing countries therefore are unlikely to reduce population growth rapidly. Correspondingly total fertility rates in the developing countries are high, although they are declining slowly (Mauldin & Segal, 1986).

How can we say if a country is successful in its attempt to provide good health and health education to your population? Well, population control is one good factor to consider. If the government of that country has a firm hold over its population control, everything else will follow through. If the country has enough population, wherein the government can fully support the needs of its people in terms of medical and other health issues (Booth and Dunne, 2002), then we can say that that country is indeed successful in providing good health to its people. And this very attribute is what the developing countries must learn to adopt.

Education

When we talk about education, members of the developing country are currently on different phases. There are countries that have quite an advanced education system because enough attention and funding are given to education itself (Kaldor, 2007). While there are others which seems that education has really been forgotten by the government.

In this research, we will be taking a look on the educational profiles of two countries which are considered to be developing – Malawi and Sri Lanka.

Malawi is a narrow, landlocked country in Southern Africa, bordered by Mozambique, Zambia and Tanzania. The country is divided into 3 administrative regions – North, Central and Southern – that reflect historical, socio-cultural and political differences (Moleni, 1999).

Malawi is found to be increasing rapidly in terms of urbanization although over 85% of the population is still found in rural areas. Infrastructure is poor, with few tarmac roads and limited access to public transport. Less than 1% of the rural population has electricity and access to clean water is problematic for both rural communities and urban townships (Moleni, 1999).

Formal schooling in Malawi was established by Christian missionaries based on their ambition to evangelize. In this respect, education for women was deemed to be unnecessary, since women could not become preachers (Grant-Lewis et al, 1990). The colonial government reinforced this and during much of Banda’s regime, female participation in education remained severely restricted. This is reflected in an adult literacy rate today of less than 42% for women (DFID 1998).

Transition rates to secondary education have increased in recent years, but remain low at 9.3%. Following completion of the Primary School Leaving Certificate (PSLC), students may be selected, on the basis of their PSLC results, to subsidized government or grant-aided secondary schools. Grant-aided schools are generally well established boarding schools run by Church organizations and are often single-sex institutions (Moleni, 1999).

As we can see, education system in Malawi is undergoing major changes. But is seems that the country is not fully ready for that. Increased enrolment had resulted in higher pupil-teacher ratios – currently 70:1. Large class sizes, resource shortages, and an inadequately trained teaching corps resulted to a low achievement and wide-scale dissatisfaction with schooling and concomitantly low school completion rates (Johnson et al, 1992). Researchers found out that only 23% of any given cohort completes eight years of primary school (Weber and Chibwana, 1999). Further, because of high repetition rates, it takes an average of 12 years to complete the eight-year primary school cycle (Ministry of Education and Culture, cited in Weber & Chibwana, 1999) and an average of 12 years to complete the eight-year primary school cycle (Ministry of Education and Culture, cited in Weber & Chibwana, 1999).

In contrast to Malawi, Sri Lanka’s achievements in education are quantitatively impressive. According to a country paper produced by DFID, Sri Lanka has a literacy rate of over 90% and the highest basic and secondary education participation in South Asia. Over the past 50 years, the expansion in school enrolment has been remarkable. Participation in grades 1-5 is now close to universal, while the proportion of pupils still at school in year 11 is close to 70%. Girls have participated in this expansion to an even greater extent than boys and gender ratios range between 92 and 95 in grades 1-5. In higher grades, the gender ratio seems to climb steadily so that by year 11, when students sit the 0 level examination, there are as many as 115 girls for every 100 boys (DFID 1998).

This increase in public demand for education has resulted in a network of accessible schools spread throughout the island. Pupils have access to a primary school within a radius of 2km, a junior-secondary school within every 5km and a senior-secondary school within a radius of 7-8 km (Hart & Yahampath, 1999).

These are just two countries having totally different population-reaction towards the new educational system. And I am sure that there are more and different stories from other countries.

Politics

Of course, politics would always be a part of any country – may it be from a highly developed country or a developing one. And politics has been also proven to be under deep scrutiny and controversies.

In most developing countries today, corruption in politics is widespread and part of everyday life. Society has learned to live with it, even considering it, fatalistically, as an integral part of their culture. In practice, it is the environment in which public servants and private actors operate that causes corruption (Kaldor, 1999). Public administration in developing countries is often bureaucratic and inefficient. And a large number of complexes, restrictive regulations coupled with inadequate controls are characteristic of developing countries that corruption helps to get around (Hors, 2000)

The link between political and economic power can be direct. There is patrimonial, as in Morocco, where access to political power ensures access to economic privileges. The link can be indirect too, as in the Philippines, where political power, such as a privileged position in a patronage-based system, can be bought and sold. In short, the process of allocating political and administrative posts – particularly those with powers of decision over the export of natural resources or import licenses – is influenced by the gains that can be made from them (booth and Dunne, 2002). And the political foundations are cemented as these exchanges of privileges are reciprocated by political support or loyalty (Hors, 2000).

Institutional analysis of corruption indicates where the remedies lie. Greater transparency, accountability and merit-based human resource management in public administration are principles which could possibly curb corruption. Simplification of state intervention in economic activity also helps. A study of the customs administration in Senegal found, using econometric tests that a reduction in import taxes, simplification of their structure, implementation of reforms reducing the discretionary powers of customs officials and computerization of procedures helped to reduce the level of fraud by 85% between 1990 and 1995 (Hors, 2000).

Simply applying anti-corruption structures that work in OECD countries cannot solve the problem of corruption in the developing countries. The experience with the latter countries have acquired in terms of legislation, public procurement codes and control procedures, for example, is valuable, but it is just a technical element in a much more complex process of change (Kaldor, 2007). A reduction in corruption depends on economic development. It is thus for each country concerned to draw up its own strategy, by which it can then lead to a virtuous circle of development and good governance (Hors, 2000).

Conclusion

There are various issues highlighted on this research paper. Issues which are now the direct concerns of the countries belonging to the so-called “developing world”.

For one, it has been realized that to be considered a developing one, there must really be significant evidences that a country is working on it. And it is not that easy. Countries aiming to be developed are facing major challenges and changes which could help them in the attainment of their goal. Like political and economic issues. These are the very foundation of a country. To face the world of the “developing countries”, politics and economy of that country will certainly face a major turn around. Really, there is a big probability that the “old” economy and political situation of the country will not be retained.

Health, population, natural resources and education is another thing. Developing countries are currently receiving assistance from different associations. And this assistance is indeed a big help to these countries. But despite all the efforts, all the helps that these developing countries are doing and receiving, still bigger problems arise, like proper sanitation and health education, education on population-control, proper usage of natural resources and the likes.

All of these summed up to one whole idea, and that pertains to the fact that there is indeed a state of poverty in the developing countries. But the good thing is that they are working hard to alleviate from that state of scarcity. More so, policy makers and leaders, even the general citizenry believe that a stable economy (backed up by good resources) plus a firm and flexible government structure must work hand in hand in the attainment of every country’s one common goal – to develop and grow for the people and by the people.

Sources

1995 Per Capita GDP. Web.

Belloch J (1886), quoted by Tarver JD (1996) in JD Tarver. The demography of Africa, p13. Praeger Publishers, Westport, USA

Booth,Ken and Dunne Tim (2002) Worlds in Collision: Terror and the Future of Global Order, Basingstoke: Palgrave

Casonde, Joseph. M.D. Reproductive Health in Developing Countries: Key Features and Key Issues. Web.

Country Profile: Norway. BBC News. Web.

Developing Countries. Web.

Developing Country. Web.

DFID. Unpublished Working paper on Sri Lanka. London DFID. 1998.

Globalization. Web.

Gyldendal’s Norwegian Encyclopedia. General info. 2003. Facts and Figures. Web.

Gyldendal’s Norwegian Encyclopedia. Labour Market. 2003. Facts and Figures. Web.

Hart, K & Yahompath, K (1999) National Basic Mathematics Survey: Sri Lanka Primary Mathematics Project. Report to DFID and Government of Sri Lanka, Cambridge Educational Consultants.

Hors, Irene. Fighting corruption in the developing countries. (2000). OECD. Web.

Hovind, Ole B. Public Health System. 2003. Facts and Figures. Web.

Johnson, D, Garrett, R M & Smith, R (1992) Survey of Primary Education in Malawi. Report to DFID. University of Bristol.

Kaldor, Mary (1999). New and Old Wars: Organized Violence in a Global Era, Cambridge: Polity,

Kaldor, Mary (2007). Human Security Cambridge: Polity

Mauldin WP and Segal SJ (1986). Prevalence of contraceptive use in developing countries. The Rockefeller Foundation, New York, USA

Mohamad, Mahathir. (2002). Globalization and Developing Countries. The Globalist. Web.

Moleni, K (1999) Addressing girls’ participation in secondary education in Southern Malawi: the GABLE Scholarship Program. Unpublished MEd dissertation, University of Bristol

Smith, Lisa C. and Haddad, Lawrence. Explaining Child Malnutrition in Developing Countries: A Cross-Country Analysis. Research Report 111 Washington, D.C.: IFPRI. 2000.

Specific Issues of Developing Countries. Web.

Third World: definitions and descriptions. Web.

Thornsnaes, Geir. Population. 2003. Facts and Figures. Web.

UK Trade and Investment. 2001. Web.

United Nations. World Population Prospects. 1990. New York

Weber, M & Chibwana, M (1999). Education in Malawi: a country profile. Unpublished working paper, University of Bristol.