Introduction

The total number of hours that an individual is capable and willfully supplies at a standard wage rate is called the labor supply. Thus supply of labor involves individuals seeking to be employed for a given an agreed amount of wage. But the neoclassical theory of individual labor supply terms income and leisure as the major source of individual utility.

Income that is generated by the individual from work is spent for the leisure activities, depending on the individual’s own preference. However, the changes in the market wage rate impacts the individual in two ways; an increase or decrease in the income and a shift from one activity to the other. In the longer term, the extreme increases and decreases in the wage rate may decline to unacceptable levels forcing individuals to exit the labor market, a situation known as voluntary unemployment (Burda & Wyplosz 2009).

Therefore, the neoclassical theory of individual labor supply is based on two assumptions. First, an individual has two likely ways of spending time; for labor and/or leisure, and secondly, the individual equitably distributed the time spent for leisure and labor in order to derive maximum satisfaction.

Because individuals alternate between working and leisure, foregoing an hour of leisure equals to the wage rate. Thus, if the value of leisure time is higher than the market wage rate, individuals would prefer not to work. In both cases, the opportunity cost of foregoing an activity equals to the value derived in the other activity. As such changes in the wage rate results in either a substitution effect or an income effect (Veblen 2010, p. 373).

Effects of wage rise

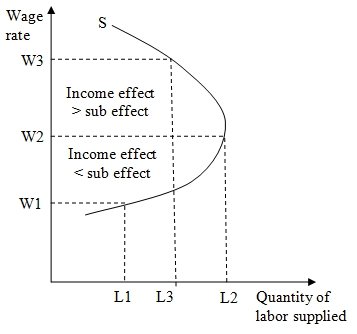

The graph below shows the supply curve resulting from changes in real wage rates and their effects on the quantity of labor supplied. For instance, real wages increased from W1 to W2 the individual would benefit from an increase in income, and increase in utility. Consequently, the individual would willingly increase their working hours from L1 to L2; represented on the graph as income effect being less than the substitution effect.

The positive price change results from the comparison of a greater substitution effect against the income effect. According to Gupta & Dutta (2010, p. 923) the resultant increase in wage rate results in to a significant climb in the opportunity cost of leisure time. The resultant costly leisure time is due to the increase in wage rate. Instead of spending more time for leisure, that is already expensive, individuals would instead prefer going to work more to increase their income. This is termed as the substitution effect result from a higher wage rate.

On the contrary, Hazan & Maoz believe that the income effect results from further increase in wage rate. From the graph, increase in wage rate from W2 to W3 would cause the labor hours to decrease from L2 to L3. According to Veblen (2010, p. 397), the wage rate increase results in a higher income effect than the substitution effect, such that an individual derives higher utility from an hour spent on leisure than from an hour spent working.

The backward bend in the supply curve results from the increase of wage rate beyond W2. Beyond W2 the individuals earns enough income to sustain their lifestyle, thus do not need to work for extra hours. Hence individuals prefer to increase leisure time and reduce the hours spent at work (2010, p. 2126).

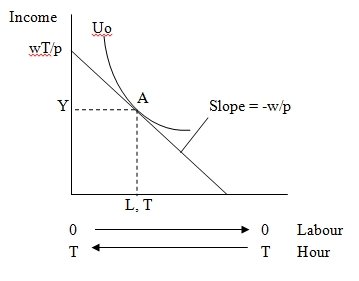

On the basis of an indifference curve-like platform, Ransom & Sims suggest that an individual’s utility function is composed of real income (Y) and leisure (L). It is represented mathematically as utility is a function of Y and L, U = U(Y,L).

Since an individual would be prompted to sacrifice some leisure time to receive additional income, an indifference curve is downward sloping, with points above the indifference cure offering higher utility than points on or below it (2010, p. 331). In order for individuals to attain the highest achievable level of utility, alternative levels of Y and L, with the limiting goods and time constraints, the full-income constraint is represented as wT = pY + wL. The equation can be in the form Y = -(w/p)L + (w/p)T, referred to as individual’s constraint.

Graphically,

From the above graph, the intercept of the budget constraint on the Y (income) axis is wT/p; giving the full income point. The budget constraint has a slope of –w/p. hence the downward slope. At the point of tangency (point A) between the indifference curve and the budget constraint, giving certain optimal levels of Y and L or Y and T, maximizes the utility (Caliendo, Gambaro & Haan 2009, p. 877).

Neoclassical theory and wage differentials

According to Aspromourgos (1986, p. 265), differences in wages exist and according to the neoclassical theory of the labor market, they should be equal. This decision was based on the assumptions of maximizing profit, perfect competition and homogeneity of workers. Nevertheless, there are three neoclassical trajectories elaborating the workers’ wage differentials; human capital theory, theory of equalizing differences, and efficiency wage theory.

According to the theory of equalizing differences, identified differences that associated with inherent traits of a specific job require wage compensations with non-monetary positive traits. In order for effective compensation, the should exist, consistency of work, agreeableness of the job, ease of learning the employment, probability of success and degree of responsibility (Caliendo, Gambaro & Haan 2009, p. 877).

The second theory, the human capital theory, attempts to explain differences in wages as resulting from an individual’s marginal capital productivity caused by differing human capital stocks such as aptitudes, training, knowledge, education and skills of an individual group are characterized. The productivity differentials are contributory to the wage differentials as the neoclassical labor market dispenses its wages depending on the marginal product of labor.

Because, human capital differences are exhibited in the varying productivity, different wages will be paid. Evidence has shown that workers possessing high education earn comparatively higher wages. Individuals that sacrifice their leisure time and finances to acquire more skills and experiences add to their human skills which translate to increased productivity (Casares 2010, p. 233).

Thirdly, the efficiency wage theory, while explaining the existence of above equilibrium wages seeks to understand why these rates result into unemployment. Because firms paid above equilibrium wages to employees in developing countries during the 1950s, the theory was coined to understand the trends.

The theory concluded that equilibrium wages were not enough to cater for the workers’ basic health. Thus paying them above the equilibrium rates ensures that their improved health would contribute to increased productivity. The employers according to the theory aimed at reducing turnover, discourage shirking and attract superior employees.

Disutility of labor and working hours

In contrast to the associated increased utility resulting to the individuals increasing their work hours, Van der Hulst, M 2003, pp. 171) postulates that certain disutility effects arise from work at the margin areas. On the basis of the standard economic theory, there are positive non-monetary effects of being employed.

Thus a relationship exists between individual well-being and working hours; whereby studies have been conducted. For instance, an increase in the individual’s working hours automatically generated an improvement on the individual’s life utility, even with a constant amount of wage/income. As such, work is considered a positive generator of utility for an individual, hence life’s utility increases with employment and working time.

According to Hazan, M & Maoz (2010, p. 2134), substantial improvement of the living standard results from a change in status from unemployed to employed, irrespective of the few hours spent working. According to the study, it was further evidenced that increasing labour hours benefits men due to the non-pecuniary utility, thereof.

Beyond the optimal labor supply of seven hours known to maximize well-being, the level of happiness is reduced. Although women just like men benefit from the non-monetary utility of additional working hors, their optimal labour time per day is four hours and any extension beyond that leads to utter discomfort. According to the neoclassical assumption of marginal labor disutility, for both sexes, the happiness maximizing labour time should be less than the average real working time.

The theory is supported because at the margin the disutility is caused by labor for the employed individuals. However, according to the happiness literature, the total utility of work for most employees is positive and not negative. Therefore, the well-being research empirical findings concur with the theory assumptions (Clark 2003a, p. 323).

A similar picture is evidenced in the evaluation of the external changes of working time that resulted into under- or over-employment. Just as noted above, the positive utility of working hours are impacted by the strong decrease in well-being resulting from external deviations from the desirable labor time. Especially, work extended beyond the utility maximizing level has a significant diminishing impact.

According to Kaufman work in addition to generating disposable income for individuals, also provides non-pecuniary utility effects. In the happiness economics, the debate point of contention is whether greater focus should be directed more on leisure than on work. Too much leisure is known to negatively impact life satisfaction, while individuals should not be forced to work long hours, because labor improves well-being.

The consequences of excessive labor time and too much leisure, such as negatively impacting the workers, eventually, affect the organization’s performance. Primarily, the major perspective should be reduction in the levels of unemployment through policy. The policy has a two-fold impact on the well-being; increase in the disposable income, and increase in the non-monetary utility of work (2008, p. 285).

If the policy regulatory measures on working hours are externally determined they will negatively impact welfare because in most cases they would conflict with the individually desired labor time. However, if internally determined, the policies are likely to match or accommodate the individual preference of the employees, hence positively impacting welfare. Due to the external policies, the feeling of under- or over-employment will contribute to decline in individuals’ well-being.

On the contrary, Mutari, Figart & Power, believe that improvement in workers welfare and happiness is associated with less restrictions and flexible working time. The benefit can accrue to companies that provide a favorable working environment and flexible working hours. Through the non-monetary utility, companies can opt to substitute the favorable working conditions and flexible working hours for a discounted wage for their employees compared to the competitors (2001, p. 23).

Voluntary unemployment and income replacement programs

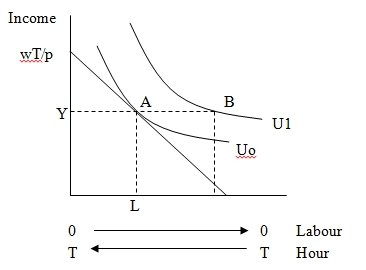

The above graph shows the point A representing an individual’s combination of H hours and L hours of leisure at a wage rate of w. Income equals to Y.

According to the neoclassical theory of labour supply, it is assumed that the only type of unemployment is voluntary in the long-run because the market is assumed to sort itself. Specifically, the movements in the market wage rate will in the long-rum reach unacceptable levels that individual would prefer not to work; instead opt out of employment (Vroman & Brusentsev 2005). In the event that an individual becomes unemployed, and all lost income is replaced, the individual moves from point A to point B, as shown below

The shift from A to B represents an increase in utility from Uo to U1 possible in the complete incomplete unemployment when an individual becomes unemployed.

Income replacement programs in the US include disability insurance, whereby an individual disabled while in employment receives income equal to the initial wage, while increased leisure hours are provided, their level of utility would increase. The assumption includes full compensation for “pain and suffering” and medical expenses (Nakamura & Murayama 2010, p. 665).

Effective insurance for the disabled workers requires approved medical physicians assigned to conduct medical examinations aimed at curtailing on fraudulent disability claims by employees. However, partial disability from a work-related injury discounts the wage that the affected worker will be paid.

Retrospectively, the income and substitution effects resulting from the wage reduction affects the quantity of labour and time spent in the working place. Because it is only the income effect that results from a loss in utility, the partially disabled employee can be compensated with a replacement scheme large enough to cancel out the income effect caused by the reduced wage. This applies when the desire is to adequately compensate the partially disabled employee (Van der Hulst 2003, p. 171).

Conclusion

Based on the neoclassical theory of individual labor supply individuals use of time for both work and leisure. This indifference in an attempt to attain utmost utility of time, and changes in the wage rate greatly impacts the level of utility attained. Neoclassical theory of labor explains the variations in the wages paid to workers through theory of equalizing differences, human capital theory and efficiency wage theory. Consequently, an increase in the wage rate results causes an income effect and substitution effect.

However, disutility in the working hours and working time exists in situations whereby excessive time is spent either in work or on leisure. Companies that provide favorable working conditions and flexible working hours have the option of paying a satisfied workforce less-than market wage rate. Furthermore, the change in the market wage rate determines the level upon which individuals prefer leisure for working; a situation called voluntary unemployment.

List of References

Aspromourgos, T 1986, “On the origins of the term ‘neoclassical’,” Cambridge Journal of Economics, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 265 -270.

Burda, M & Wyplosz, C 2009, Macroeconomics: A European Text, 5th edn, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Caliendo, M, Gambaro, L & Haan, P 2009, The impact of income taxation on the ratio between reservation and market wages and the incentives for labour supply, Applied Economics Letters. London, vol. 16, no. 9, p. 877.

Casares, M 2010, “Unemployment as excess supply of labor: Implications for wage and price inflation”, Journal of Monetary Economics, vol. 57, no. 2, p. 233.

Clark, A 2003a, “Unemployment as a Social Norm: Psychological Evidence from Panel Data”, Journal of Labor Economics, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 323-351.

Clark, A 2003b, “Unemployment as a Social Norm: Psychological Evidence from Panel Data”, Journal of Labor Economics, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 289-322.

Colander, D, Holt, R & Rosser, B 2004, “The changing face of mainstream economics,” Review of Political Economy, Taylor and Francis Journals, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 485-499.

Gupta, MR & Dutta, PB 2010, Skilled-unskilled wage inequality, nontraded good and endogenous supply of skilled labour: A theoretical analysis, Economic Modelling, vol. 27, no. 5, p. 923.

Hazan, M & Maoz, YD 2010, “Women’s lifetime labor supply and labor market experience”, Journal of Economic Dynamics & Control, vol.34, no. 10, pp. 2126-2134.

Kaufman, B 2008, “The Non-Existence of the Labor Demand/Supply Diagram, and other Theorems of Institutional Economics,” Journal of Labor Research, vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 285-299.

Mutari, E, Figart, DM & Power, M 2001, “Implicit Wage Theories In Equal Pay Debates In The United States,” Feminist Economics, Taylor and Francis Journals, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 23-52.

Nakamura, T & Murayama, Y 2010, “A Complete Characterization Of The Inverted S-Shaped Labor Supply Curve”, Metroeconomica, vol. 61, no. 4, p. 665.

Ransom, MR & Sims, DP 2010, “Estimating the Firm’s Labor Supply Curve in a “New Monopsony” Framework: Schoolteachers in Missouri”, Journal of Labor Economics, vol. 28, no. 2, p. 331.

Van der Hulst, M 2003, “Long work hours and health”, Scandinavian Journal of Work and Environmental Health, vol. 29, pp. 171-188.

Veblen, T 2010, “Why is Economics not an Evolutionary Science? Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 373-397.

Vroman, W & Brusentsev, V 2005, Unemployment compensation throughout the world: a comparative analysis, Michigan, W.E. Upjohn Institute.