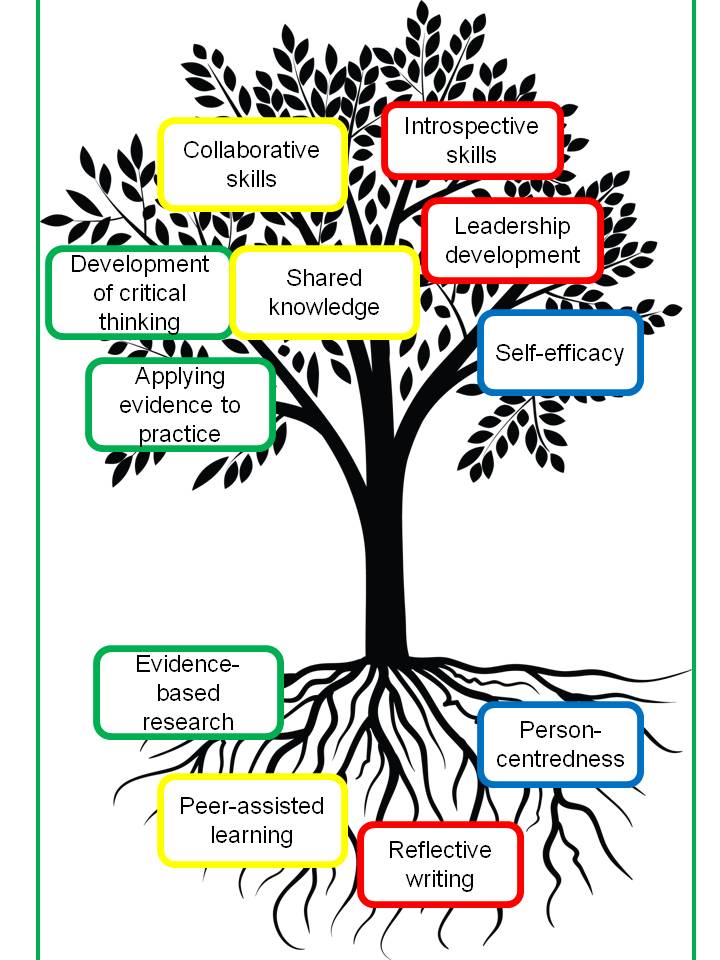

Reflective skills revealed through the process of self-analysis are essential for a person-centered development of a professional. According to Kolb’s learning cycle model, a reflective observation that implies reviewing the task and the role of the person in it is one of the four critical elements of the process. As Driessen (2017, p. 223) defines it, a portfolio is “a reflection on an aspect that is considered important to learning or profession.” Rowley, Mundy, and Polly (2017) see reflective portfolios as methods to enhance the development of professional identity. Overall, writing a reflective portfolio contributes to professional development due to constant self-monitoring and transformation. The process of introspection helps to reveal a personal perception of the self, identify strengths, and set developmental goals. Moreover, this method helps to assess self-efficacy, which is essential for the completion of the tasks and reaching the goals.

Although the majority of scholars agree on the necessity of reflective skills, there is still a discussion regarding the efficiency of portfolios in pursuit of this goal. Many believe that conducting a multi-faceted evaluation of personal and professional development in this format can enhance self-efficacy and promote person-centered practice (Martin, Slade, and Jacoby, 2019). This way of self-knowledge is especially significant for the development of leadership skills due to the person-centered approach to leadership. Scholars claim that “knowing ‘self’ represents a key prerequisite of being an effective person-centered facilitator” (Middleton, 2017, p. 1). Schedlitzki (2019) also believes that leadership learning benefits from the portfolio as a form of self-evaluation.

Faculty and educators’ perspectives should also be taken into account while assessing the efficiency of portfolios. According to Pandya, Slemming, and Saloojee (2017, p. 78), they assist in “monitoring students ‘ growth over time, identifying learning gaps, and helping to establish if expected learning outcomes were being attained.” From the point of view of interprofessional cooperation, portfolios are essential to demonstrate self-assessed skills and knowledge to engage in collaboration with other professionals (Domac, Anderson, and Smith, 2016). Driessen (2017) argues that students often face this task with resistance due to the imperfect application of the method. According to Driessen (2017, p. 221), the ethics and efficiency of these reflections are often questioned. To avoid bureaucracy resulting from the completion of the portfolio, the scholar suggests that the process should be carefully guided by a mentor (Driessen, 2017). The idea is reasonable as it helps to reinforce the potential of portfolios to boost the development of reflective skills.

Portfolios are potentially robust educating and developmental tools used to increase the reflective skills of professionals. To maximize the contribution of a portfolio, a comprehensive, mentor-led approach should be taken. Overall, portfolios provide the possibility of introspective analysis of the progress, which is essential in setting further goals and targets. Moreover, this method of self-evaluation can serve multiple purposes, including leadership development, interprofessional, or educator-student relationships. Therefore, the information can be used not only for self-evaluation but also for sharing it with other people who can positively contribute to professional development.

Reference List

Domac, S., Anderson, E.S. and Smith, R. (2016) ‘Learning to be interprofessional through the use of reflective portfolios?’ Social Work Education, 35(5), pp. 530-546.

Driessen, E. (2017) ‘Do portfolios have a future?’ Advances in Health Sciences Education, 22, pp. 221-228.

Martin, A. J., Slade, D., & Jacoby, J. (2019) ‘Practitioner auto-ethnography: developing an evidence-based tertiary teaching portfolio’, International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning, 20(3), pp. 301-308.

Middleton, R. (2017) ‘Critical reflection: the struggle of a practice developer’, International Practice Development Journal, 7(1), pp. 1-6.

Pandya, H., Slemming, W., and Saloojee, H. (2017) ‘Reflective portfolios support learning, personal growth and competency achievement in postgraduate public health education’, African Journal of Health Professions Education, 9(2), pp. 78-82.

Rowley, J., Munday, J., and Polly, P. (2017) ‘Preparing future career-ready professionals: a portfolio process to develop critical thinking using digital learning and teaching’, in Auer, M. E., Guralnick, D., and Simonics, I. (eds.) Teaching and learning in a digital world. Budapest: Springer, pp. 702-707.

Schedlitzki, D. (2019) ‘Developing apprentice leaders through critical reflection’, Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning, 9(2), pp. 237-247.