Abstract

The holistic development and mental wellbeing of a child depend on the stability of the family in which one grows. Children from stable families and supporting parents tend to become responsible citizens and successful adults. On the other hand, children from dysfunctional families where violence and crime are common activities learn to embrace such antisocial practices. In this paper, the researcher explains societal views on refugees and the effects of migration and integration on children’s holistic development and mental wellbeing. The study shows that refugees have often received the support of the international community as they try to protect their lives away from their countries. However, the increasing cases of extremist attacks and violent crimes committed by some asylum seekers are changing the perception. There are fear and resentment that many currently have towards refugees. The instability that refugee children suffer significantly affects their development and mental wellbeing. They are most likely to become engaged in crime as they become youths.

Refugee Definition, Background, and Societal Views

Definition of Refugees

The term refugee has received different definitions from various organizations, but they all bring out the same meaning. Taken from the word refuge, which means protection or shelter from distress or danger, this term has been defined in various ways by different organizations and scholars. Goularas, İpek and Önel (2020) define it as “a person who has been forced to leave their country to escape war, persecution, or natural disaster.” This definition emphasizes the fact that a refugee is forced to seek asylum in a foreign country because of persecution, internal conflicts, or natural disasters. They feel that if they do not leave their homes, they may be exposed to grave danger. According to the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), a refugee is a person “who has fled war, violence, conflict or persecution and has crossed an international border to find safety in another country.” This definition excludes internally displaced persons who are expected to get the protection and care of their governments. When an individual crosses the international border because of the reasons given above, they will be considered refugees based on the definition of UNHCR.

The Organization of African Unity (OAU), currently the African Union (AU), defined a refugee as an individual “who, owing to external aggression, occupation, foreign domination or events seriously disturbing public order in either part or the whole of his country of origin or nationality, is compelled to leave his place of habitual residence to seek refuge in another place outside his country of origin or nationality” (Abouarab 2019, p. 56). This definition broadens the scope of factors that can force an individual to become a refugee. External aggression, occupation, and foreign domination are factors that the UN avoided using in its definition, but OAU identified as possible reasons that may force an individual to seek asylum in a foreign country (Parekh 2020). Just like the definition given by UNHCR, the OAU also believes that an individual becomes a refugee when they cross the border of their country of origin to a foreign country.

Latin America also had its definition of refugees as the problem became increasingly common in the region during the 1970s and 1980s because of civil war and other internal factors. The Cartagena Declaration on Refugees defined it as “persons who have fled their country because their lives, safety or freedom have been threatened by generalized violence, foreign aggression, internal conflicts, massive violation of human rights or other circumstances which have seriously disturbed public order” (Brown 2019). This definition, just like the one given by OAU, identifies foreign aggression as a potential factor that can force people to become refugees. It goes further to identify a violation of human rights, which OAU avoided mentioning, as another potential threat that can cause the problem.

Definitions provided above all demonstrate the fact that a refugee is a person who is forced out of their country to a foreign nation because of a threat to their lives. They leave their homes, involuntary and not knowing when it will be safe for them to come back, to any foreign country with the primary goal of protecting their lives. Different organizations provide different factors that may lead to a refugee status, which helps in determining their views on this issue. UNHCR believes that internal conflicts, persecutions, and natural disasters are some of the main factors that may force an individual or a group of people to seek asylum. The institution emphasizes the fact that internal leadership of a given country is primary responsible for managing this problem. A government that fails to manage internal armed conflicts and persecutes a section of its citizens because of their political views creates instability and insecurity that forces some citizens to seek asylum in foreign nations.

OAU believe that external aggression, foreign domination, occupation, and disturbance of public order are the main sources of the problem (Jansen & Lässig 2020). It is important to note that their definition left out factors such as persecution, internal conflicts, and natural disasters as potential causes of the problem. As Teller (2020) notes, this definition tends to place the blame on foreign forces as the main cause of the mass displacement of people from their homes. The same view is evident in the definition given by the Latin American countries. These two regional blocks have often felt that foreign powers have been interfering with their normal socio-political and economic structures unfairly. Such interference causes major political rifts that cannot be effectively addressed in peaceful democratic elections (Diemer 2016). As such, they hold the view that this problem is a creation of the leading economies such as the United States and countries within the European Union.

Background: Historical, Social Policy, and Professional Analysis

The practice of asylum-seeking can be traced back to most of the ancient kingdoms in Africa, Europe, and Asia. In ancient Greece, anyone who sought sanctuary in a holy place was not to be harmed because doing so would invite divine retributions (Juss 2019). The same practice spread to ancient Egypt as it was believed that such an individual had divine protection. In 600 AD, Aethelberht I, king of Kent, issued a decree that anyone who sought asylum in church or any holy place was not to be attacked by an individual or state agencies (Sciaccaluga 2020). This law gained popularity and spread to other European nations during the middle ages. It was seen as a sign of surrender and that the asylum seeker no longer posed any threat. The word refugee gained popularity when the League of Nations established the High Commission for Refugees to help those who were forced out of their country of origin because of various threats to their lives.

When the First World War ended in 1918, many people were displaced, with others forced to seek asylum outside their country of origin. The League of Nations was faced with the challenge of settling those who had been displaced during the war. The High Commission for Refugees was established in 1921 and Fridtjof Nansen was appointed to head it (Annamalai 2020). The immediate concern was to find ways in which this global community could resettle those who were displaced in the war. The victims of the Russian Revolution and the Russian Civil War became the immediate beneficiaries of this organization, especially after Lenin revoked Russian expatriates’ citizenship in 1921 (Parekh 2020). Survivors of the Armenian Genocide and Jews who fled from Eastern Europe, especially Russia, became the beneficiaries of this organization as they sought asylum in foreign nations around Europe and North America.

The United Nations High Commission for Refugees was founded in 1950 to take over the responsibilities of the defunct organization that had been established by the League of Nations. Since then, this organization has played a major role not only in helping refugees to seek asylum out of their countries of origin but also in shaping the international societal views on refugees (Kehnscherper 2017). This organization has been working with individual states in Europe, Africa, Asia, North America, South America, and the Middle East to ensure that those who are fleeing their homes are offered the protection that they need (Croegaert 2020). Africa, the Middle East, Central and South America are some of the regions that have been worse hit by the problem of civil strife and political persecutions, leading to high numbers of refugees.

The perception that society has towards refugees often defines the approach that they take when responding to the need to assist asylum seekers. Henry (2020) explains that after the Second World War, the United Nations, through UNHCR, was successful in inculcating sympathy towards refugees. They were viewed as victims of circumstances beyond their control. The majority had been displaced during the war and others were displaced because of internal conflicts caused by weak governments after the war (Bradley, Milner & Peruniak 2019). As such, the global community was willing to provide the necessary support to ensure that their basic needs were met in these foreign countries. The United States and European Union played a major role in providing financial assistance to states and non-governmental organizations that were providing direct support to these displaced persons. The UN has enacted various social policies meant to protect the refugees since then and most of the member states have ratified these policies.

During the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, and part of the 1990s, many countries in Sub-Sahara African, Central and South America, and the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) went through a period of civil strife. The Rwandan genocide of 1994, the Nigerian Biafra Wars, the Chechen War of 1992, and the Gaza-Israel conflict are some of the notable international conflicts that have left millions homeless, with a significant number seeking asylum in foreign countries (Schnyder & Shawki 2020). These conflicts were mainly blamed on poor governance in these countries and negative ethnicity.

Some leaders of these countries have blamed the West for causing instability in their countries. Albanese and Takkenberg (2020) state that the argument about foreign interference in the governance of these countries is debatable. For instance, the United States and the Soviet Union were directly involved in the Vietnam War that left thousands dead and hundreds of thousands of families homeless. During this period, the global society had a favorable view towards refugees (Weiwei 2020). The problem has persisted and most recently, the Arab Spring that started in 2010 left millions of people from Syria, Yemen, Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, and Bahrain seeking asylum in various countries in Europe and the United States.

The migration and integration of these refugees have a major impact on children’s holistic development and well-being. McGee (2020) explains that a child needs socio-economic stability to achieve holistic development. They need to interact with their peers normally and have stable homes and families where they can get the support they need (Rioli 2020). They should also have the acceptance of the immediate community. The constant movement from one place to another denies them the stability that they need at this critical stage of development. Fiddian-Qasmiyeh (2020) note that the situation can be made worse in cases where they are forced into societies that do not have favorable views towards specific foreigners. When they are constantly rejected in these societies and considered a source of threat or a bother, then they develop fear and resentment. They do not feel they belong to society. Inferiority complex would define their personalities as they are forced to learn to give priority to the locals.

Societal Views on Refugees

The perception of society towards refugees has been varying over the past several decades. According to Cimatti (2016), for a long time, there has been a favorable societal view on refugees. They are always considered victims of wars and natural disasters. When UNHCR was created, its founders understood the significance of helping those who were displaced from their homes because of forces beyond their control. The events of the First and Second World Wars were major reminders that sometimes one cannot control certain events in society. People had to flee from their homes to save their lives. Many were forced out of their country because of the hostility they faced from those who were in power. As such, there has always been sympathy towards these displaced persons. The international society has been committed to ensuring that they are supported.

Children who are part of refugees have always received more favorable treatment. As a child, stability is one of the critical factors of holistic development and mental wellbeing. They need to attend school and play with their friends in a peaceful environment where they can get the support that they need. Unfortunately, this is not always the case. When they are displaced, they are forced to endure the hardship that their parents and family members go through when seeking refuge. They have to suspend their academics to ensure that they protect their lives. Many children have lost their lives as they emigrate from their home country because of stability. Others are forced to stop their education altogether, especially those who are in war-torn parts of Asia and Africa (Elliott and Earl, 2018). The international community is always sympathetic towards these children, and an effort is always made to ensure that they are given appropriate support to protect their mental and physical wellbeing.

It is important to note that the societal view of refugees has been changing over the recent past because of events that have been happening over the recent past. The instability in the Middle East and Northern Africa (MENA) region, especially after the War on Terror and the Arab Spring, has resulted in millions of people being displaced from their homes (Fernández-Aráoz, Roscoe and Aramaki, 2017). The problem is that within the same region, anti-west extremist groups such as Al Qaeda and ISIS have enjoyed a massive following over the past several years. These terror groups have blamed the United States and Western European countries for destabilizing the region. As such, they have been planning and executing attacks against these countries that they have classified as enemies. They have had successful attacks against the United States, United Kingdom, France, and Germany among others with varying degrees of devastation.

The problem that has been experienced is that the majority of these terrorists camouflage as refugees. They leave their country to their United States or Europe as people who need assistance, but their goal is to plan and execute attacks on these countries. The sophisticated defense system that these western countries have put in place, especially after the September 11, 2001 Al Qaeda attack on the United States, makes it almost impossible for them to organize successful attacks while they (the extremists) are in their home countries (Garst et al., 2019). As such, they pretend to be part of the refugees so that they can be given refuge in these targeted countries. The majority of them are directly responsible for the stability at home so that they can justify the need for them to seek asylum. They join their victims (genuine people who are displaced by these wars) and travel out of these countries with the primary goal of attacking their host countries.

These events have redefined the perception that society has towards refugees. The sense of trust has been lost as many people in the west and other parts of the world continue to witness attacks perpetrated by some of these refugees. A fear has emerged that a significant number of these refugees are not genuine asylum seekers. According to Girma (2016), many governments across Europe, especially in Germany, the United Kingdom, Italy, Spain, and France have had a challenging experience when handling these refugees following the Arab Spring. On the one hand, they have to remain responsible to the international community and United Nations’ convention on refugees by granting asylum status to those who cross into their borders from the MENA region. On the other hand, they are faced with a growing public concern about their safety after some extremists’ attacks were witnessed in different parts of Europe. The compassion and commitment that the global society had towards refugees are fast eroding and their place fear, rejection, and resentment are growing (Girma, 2016). This is likely to significantly affect children’s holistic development and mental wellbeing.

Research Themes and Question

The primary theme of this study is to develop a better understanding of refugee’s lives, identify barriers of prejudice and stereotyping against these communities, and recommend ways of overcoming them. The goal of the researcher is to establish the impacts are of being a refugee, both the advantages and disadvantages this journey may bring into an individual’s life and the outcomes that these factors may have. The study will define who a refugee is and reasons as to why they may choose to migrate from their country. The following are the specific questions that the researcher seeks to answer through this investigation:

- What is the refugees’ migration and integration process?

- What are the factors that may affect children’s holistic development and mental well-being?

- What is the impact of the migration and integration on children’s holistic development and mental well-being?

- What are the societal views on refugees?

Analysis of the Main Themes and Theoretical Perspectives

The previous section has provided the definition of various terms and a detailed discussion of the perception of society towards refugees. In the United Kingdom and the rest of Europe, there has been an influx of refugees following the Arab Spring (Suddler, 2020). This happened at a time when the global community was getting increasingly concerned about crimes committed by people granted asylum status. According to Hunt and Fedynich (2019), there has been a growing trend of refugees sneaking out of their camps and committing various forms of crime. The problem has been witnessed in Kakuma in Kenya where Somali refugees have been accused of engaging in criminal activities. Many European nations such as France, Germany, and the United States have also witnessed such cases of crime committed by those granted asylum.

According to Irop and Kryvovyazyuk (2018), crimes committed by these people vary significantly. Some of these refugees are involved in minor criminal offenses intended to get basic needs such as food and clothing. Once people are granted asylum in another country, it is the responsibility of the host nation and the international community to ensure that they are offered basic needs (Elrod and Ryder, 2021). The problem is that sometimes the host nation may be overwhelmed, especially when millions of people from Yemen and Syria moved to Europe during the Arab Spring (Karagianni and Montgomery, 2018). Some of these refugees may move out of the camp to find food when they are neglected for too long. They are likely to engage in criminal offenses such as stealing.

Studies have shown that a section of those who are moving out of their countries to foreign nations as refugees are parts of large criminal syndicates with specific intentions. In most of the cases, they are often part of the problem that forces people out of their country (Thompson, Bynum and Thompson, 2021). They cause civil strife to justify the need for some of them to be accepted in their targeted nations as refugees. Once they are in these countries, they work as a unit to commit major crimes such as terror attacks. The host nation cannot identify these criminals when taking in asylum seekers. Louis and Murphy (2017) explain that the most worrying trend is that currently, women and children have been involved in such major criminal activities. They know that it is less likely for these children or women to be suspected as members of a larger gang.

Youth offending is becoming a major concern among various nations around the world, including the United Kingdom. The number of young people engaging in criminal activities in the country has been increasing, especially as the country continues to receive more refugees (Goldkind, Wolf, and Freddolino, 2018). Some of these young offenders are refugees. Managing this problem is a major concern because some of these visitors consider local prisons as being safer than the environment back home (Mathias, 2017). Others have joined crime because events that forced them to flee their homes and the lack of stability that followed thereafter destabilized their holistic development and mental wellbeing. It is important to investigate factors linked to involvement in crime, the impact of structural inequality, and the social composition of the prison (Chase, 2020). The section also looks at effects of policing strategies and the country’s youth justice system on youth offending, young people’s perspective of offending, and theories that can help in explaining these concepts.

Factors Linked to Involvement in Crime

The goal of this study is to find a way of addressing this problem of youth offending, especially those who have been granted asylum status in the country. To find a solution to the problem, it is necessary to start by investigating the cause of the problem. According to Mayfield, Mayfield and Wheeler (2016), one of the leading factors of youth offending is the instability of the family. As one grows up, there is a need to have a stable family that offers both emotional and material support. Some of these youths have been forced to lead a life where they lack parental guidance that can enable them to lead responsible lives. They enter the adolescent stage knowing that the only way through which they can get what they need is to use force and other illegal strategies.

The neglect that some of the youth experience in the country has been considered a factor linked to involvement in crime. McKibbin and Fernando (2020) argue that adolescence and young adulthood are sensitive stages of one’s development. These people need the attention of society in various aspects. When they feel ignored by the people they look up to for guidance and support, they can easily join criminal gangs where they will feel accepted. Meleady and Crisp (2017) believe that ISIS was able to recruit so many people from European nations because they appealed to this section of the youth. They promised them the emotional and social support that they felt they lacked at home as long as they agreed to be part of the group. As society continues to be indifferent to the youth, crime is likely to become more common in the country.

Economic challenges have been one of the major factors linked to involvement in crime in the country. Every youth hopes to get stable employment or some form of financial support that can enable them to meet their personal needs beyond the basic requirements (Rathore, 2019). For refugees, the hope of getting gainful employment in a foreign nation is always minimal. When youths lack a stable source of income, they become highly susceptible to criminal activities. They may be easily tempted to join criminal gangs as a way of earning their daily income (Mishra, Lama and Pal, 2016). Creating some form of employment for these youths may be the best way of addressing such a problem.

The growing radicalization of the youths is another major possible cause of youth’s involvement in criminal activities. A section of youths in the country has been convinced that the government is unfairly involved in the geopolitical activities in the Middle East and Northern Africa region. These radical groups have blamed the United States and its allies for creating the current political instability in the region, specifically in countries such as Iraq and Afghanistan. As such, they feel it is justified for them to launch retaliatory attacks against those who they consider their enemy (Park, Burgess and Sampson, 2019). Most of these radical groups lack proper military training and capacity to launch a meaningful attack on the country’s military installations. Therefore, they go for soft targets that cannot put any resistance. Cases where these extremists open fire on civilians at church, in school, at the workplaces and various other social gatherings have been witnessed in the recent past (Mumford et al., 2017). They feel that it is their moral obligation to fight against a government that they believe is oppressing their people.

The feeling of rejection can be a major source of the problem linked to involvement in crime. When a country allows refugees into its territory, there is always a level of responsibility that it accepts. In most cases, these refugees are expected to remain within a given residence and to avoid traveling to various parts of the country until they have the permission to do so (Patel, Poston and Dhaliwal, 2017). However, they should not feel rejected by the host nation. A feeling of rejection may make them embrace radical ideas. Some of these youths are often hopeful that if they make it to Europe from their war-torn countries, they will have a better opportunity to succeed in life (Rothblum, 2020). However, when they are rejected, their hope is lost and they can easily be influenced to join criminal gangs.

Impact of Structural Inequality on Youth Offending

The structural inequality in the country has been blamed as one of the possible causes of youth offending in the country. Pretorius, Steyn and Bond-Barnard (2018) observe that capitalism has been criticized as a concept that creates an avenue for the few to gain more wealth than they can ever use in their lifetime while leaving the rest with very little to meet their basic needs. Despite the criticism, it has proven to be the only realistic economic ideology in such a competitive society. Russia and China, which tried to spread communism to the rest of the world, have become the leading capitalistic nations in the world (Kane et al. (2018). They realized that communism was slowing their economic growth, promoting laziness, and creating an environment where people were not appropriately rewarded for their effort and creativity.

Capitalism has created a system where structural inequality cannot be easily eliminated in society. Those who control means of production have the best capacity to become richer while those who are struggling to earn a living are less likely to overcome their economic challenges (Wang, 2018). A child from a poor family will be forced to attend public schools where resources are limited, which means that their academic success will be compromised. On the other hand, a child from a rich family will attend some of the best private schools where all the necessary resources are made available for them, making it easy to achieve success (O’Neill, 2019). Upon graduation, such a child will be employed easily because of the connections of their parents.

Children from poor families struggle to achieve success in their lives. Shaikh, Bean and Forneris (2019) observe that these children are more likely to drop out of school than their colleagues from more financially stable families. When they drop out of school, their only source of income would be to do odd jobs which pay minimal salaries. It means that they would also become poor parents and the vicious cycle of poverty will continue in their lineage (Kostouros and Thompson, 2018). The structural inequality in society can easily promote crime among socially underprivileged people. They may consider crime as the only way of getting what they need.

Structural inequality may have a major impact on youth offending in the country. Shamira and Eilam-Shamir (2017) note that peer pressure is a major problem among adolescents and youth adults. The need to be like their friends and to have what their colleagues have may push many into crime. When a youth from a poor family has friends from rich families, the economic disparity may become an issue. The poor parent lacks the financial capacity to purchase some of the things that the child may need to lead a lavish life like their friends (Melde and Weerman, 2020). Peer pressure can push these youths to engage in criminal activities to earn some money that they can use to meet their needs. Theft is always one of the most common criminal acts that they consider (Kidman, 2018). Another common crime among the youth, especially those in college and those who dropped out of school, is the selling of drugs (Cox, 2018). The problem is that at the onset, these youths engage in low-key criminal activities. However, they slowly graduate to more serious offenses such as robbery with violence and major drug trafficking. They become a major threat to society and themselves.

Social Composition of the Prison Population

When one is arrested for engaging in a criminal activity, they will be taken through the justice system and when found guilty, they may receive varying sentences, from warnings and community services to fines and imprisonment (Van and Bourke, 2017). Although imprisonment has received criticism as a means of correcting offenders, it remains the most preferred way of punishing hardcore criminals who pose a major threat to members of the public (Skorková, 2016). A demographical analysis of prisoners often demonstrates their composition in terms of class, gender, ethnicity, ability, education, health, age, and substance use. Some members belonging to a specific demographic are more likely to engage in crime than others.

In terms of social class, people from rich families are less likely to become prisoners because of various factors. As Sherif (2018) suggests, a significant number of those who are incarcerated committed economic crimes. Some were trying to earn a living through illegal means because of the high cost of living. Those from poor families are less likely to face the same challenge. The neighborhood in which the poor live is prone to crime. Children grow up knowing that sometimes it is okay to use violence to achieve what one needs. Such an environment eventually defines their personality (Stariņeca, 2016). Another major factor why the rich are less likely to be imprisoned compared with the poor is that they can pay high legal fees to get the best representation when they commit a crime. With such effective defense attorneys, they can have their cases dismissed or they can serve non-custodial terms. Others even consider bribing judges to ensure that they get a favorable ruling. The structural inequality in society disfavors the poor, which explains why they form the majority of prisoners all over the world.

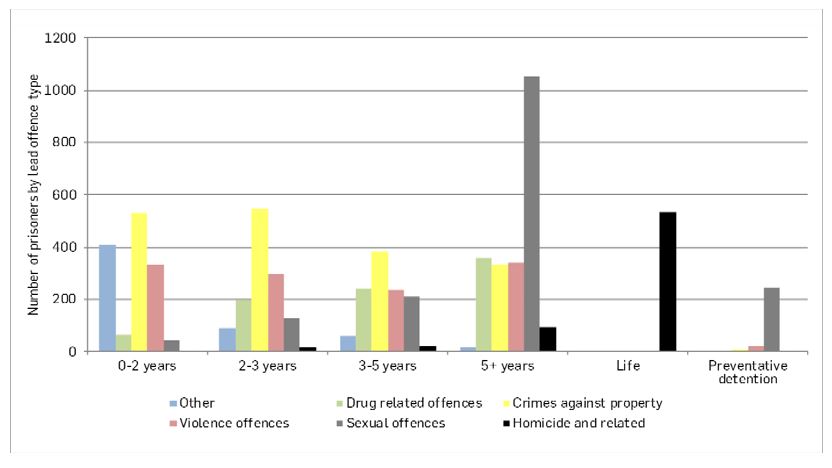

Some of the most common offenses that would earn an individual a jail-term include drug-related offenses, crime against property, violent offenses, sexual offenses, and homicide cases. The time that one would serve in prison depends on the severity and time of the crime that one has committed (Strielkowski and Chigisheva, 2018). Crime against property is classified as one of the less serious offenses and is likely to earn an individual less than five years in prison, and in most of the cases, it would be 2-3 years, as shown in figure 1 below. Drug-related offenses are classified as serious crimes depending on the degree of trafficking and strategies that one uses to evade arrest and prosecution. Sexual offenses is another higher level of serious crimes that when one is convicted, can serve more than five years. A life sentence is more common among those who are convicted of homicide and related crimes.

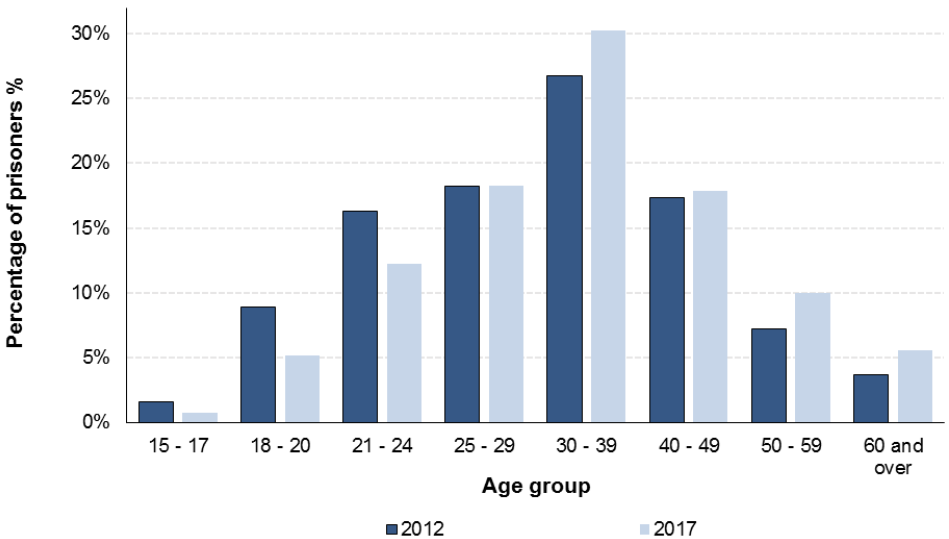

When assessing the demographics of those who are in prison, age is another important factor. As shown in the figure below, teenagers aged 15 to 17 years are the least likely people to be sent to prison. At this age, the majority are in school with ambitions of becoming successful people in life. Unless they come from dysfunctional families, such teenagers are less likely to engage in crimes that can earn them jail terms. The second category is those aged 18 to 20 years. These are college-going young adults who still have hope of achieving success in life. However, their rate of being incarcerated is more likely than the younger group. Those aged 21 to 24 have just completed college and are keen on finding stable employment (Kratcoski and Edelbacher, 2018). Their incarceration rate is higher than the younger groups. The fourth category is those aged 25 to 29 years. As shown in the graph they are more likely to be imprisoned than the previous group, although the difference is not significant. The next group are those aged 30 to 39, and are the most likely individuals to end up in prison. In 2012, they formed 27% of prisoners in the United Kingdom. In 2017, their composition increased to slightly over 30%. At this stage, those who have not gotten stable employment become frustrated. They have a family to support, the energy to work, but lack the opportunity to meet their needs (Tu and Lu, 2016). They easily consider crime as the only alternative to become successful in their lives. The composition of those incarcerated drops among those aged 40-49. These people have learned to cope with socio-economic stresses in their lives. The rate further drops among those aged 50 to 59 years. They have resigned to their fate and accepted things as they are. Individuals over 60 years are some of the minority groups in prison. They lack the energy and motivation to engage in violent crimes.

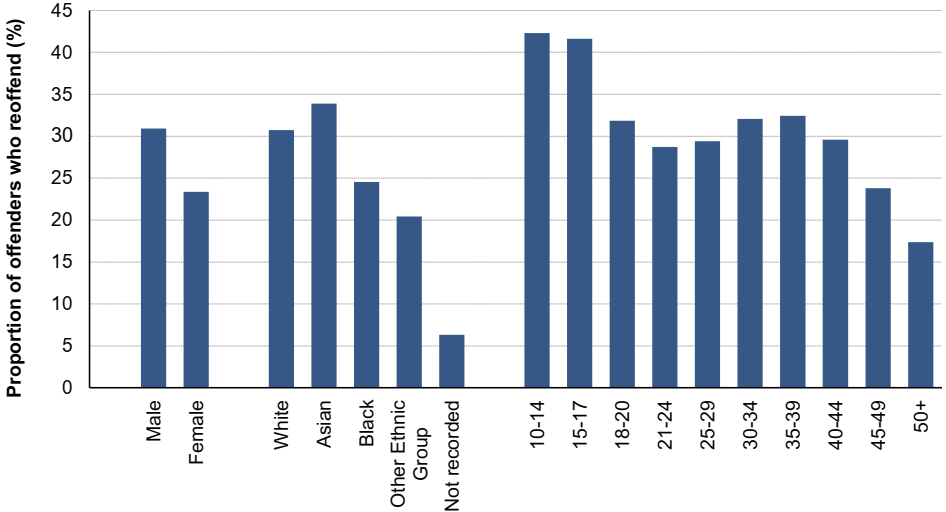

Ethnicity or race is another major factor that one may consider when assessing the demographics of those who are incarcerated in the country. A report by Fazel and Betancourt (2018) indicated that there is a disproportionate representation of blacks in the United Kingdom’s prisons than their actual population in the country. The reason why black offenders are more likely to end up in prison has been a major public discourse over the past decade. Figure 3 below shows that among those who are in prison for repeat offenses, the majority are Asians. Whites form the second-largest proportion of those who are repeat offenders while blacks come in position three. It means that most of the blacks are likely to be given long prison time when convicted of their first crime than the rest of the races in the country.

Gender is another factor that may be considered when assessing the composition of prisoners in the United Kingdom. Bhabha, Kanics and Senovilla (2018) observe that it is always a general belief that men are more likely to commit crimes than their female colleagues. The claim is confirmed by recent statistics, as shown in figure 3 below. The majority of those who are in prison are men (Thompson and Thompson, 2020). However, it is important to note that the proportion of female prisoners is rising fast relative to that of men. In 1990, the ratio of men to women in prison was greater than 2:1. It meant that for every female prisoner in the country, there were more than two make prisoners. However, that has changed significantly as shown in the figure below. If the trend continues, there will likely be as many females incarcerated in the country as there are males.

Education is another major factor that defines the composition of prisoners in the country. According to Reynolds and Bacon (2018), those with advanced education are more likely to get gainful employment than their colleagues with limited education. It means that they are more likely to lead better lives. They understand the law and are more likely to break it, especially out of ignorance (Megele, Simpson and Buzzi, 2017). When they commit an offence, they understand their rights and would not implicate themselves upon their arrest. They will get proper representations, which most likely will keep them out of prison (Dapin, 2020). These individuals know various ways of solving conflicts, especially going to court when offended, which means that they are less likely to taking the law into their hands. As such, their composition in prison is lower than those with limited education.

Substance use remains one of the most problematic factors among the youth in the United Kingdom and the rest of the world. According to Madziva and Thondhlana (2017), the ratio of prisoners who abuse drugs to those who do not is 4:1. It means that 75% of those who are in prison abuse some form of drug or alcohol, although that may not be the reason why they were arrested. The problem of drugs may be assessed from three perspectives (Blaemire, 2019). The first is the group of those who have embraced drug trafficking as their only source of income, which means that their arrest and imprisonment are directly linked to drugs. The second group is those who are forced to rob, steal or commit other crimes because they are addicted to drugs back lack money to finance their addiction. The last category is those who commit other crimes such as assault because they are intoxicated after taking drugs.

Effects of Policing Strategies and the Responses of the Youth Justice System

The government has been keen on redefining policing strategies to make it more friendly to the public and effective in keeping law and order. There has been a concerted effort to ensure that the department employs unique strategies that can ensure that they are proactive when dealing with all forms of crime. The reactionary strategy that has been a standard practice may pose a major threat to members of the public (Fazel and Stein, 2002). As such, using relying on intelligence and acting upon it in time is critical in ensuring that threats are neutralized early enough before these criminals can succeed in committing a crime. However, a section of society still feels that the police still use unnecessarily excessive force against a section of society. It has created enmity between the law enforcement agencies and a section of society (Song and Song, 2019). The problem of such hostility is that the police may not get the much-needed intelligence from these people at a time when it is necessary. It makes the work of policing more complex, dangerous, and frustrating.

The youth justice system has also gone through a major transformation over the years to make it more effective in reforming the youth instead of emphasizing punishment when convicted of various forms of crime. According to Hodes and Vostanis (2019), the justice system is currently keen on giving non-custodial sentences to first-time offenders of less-serious crimes. Studies have shown that youths are more likely to become hardened criminals after serving a term in prison. For that reason, an effort has been made to use other forms of correction that minimizes the chances of them going to jail. Just like the law enforcement agencies, the justice system has been criticized for being biased against minorities, especially immigrants and people of color (Samara et al., 2020). It compromises its ability to fairly discharge its duties.

Young People’s Perspectives of Offending

Young people who are involved in various forms of criminal activities often have some false justification for their offenses. The majority know that what they are doing, such as drug peddling, theft, robbery, and the use of violence to achieve specific goals, is a crime (Úcar, Soler-Masó, and Planas-llad, 2020). However, they go ahead and engage in these activities because they believe society has neglected them. Some of them had unstable families while others lacked the same. They grow up being bitter with society and believe that they would have become responsible citizens if they received the support they think they deserved (Pycroft and Gough, 2019). They view crime as their only way of getting what they need. They know that their actions are harmful to their targets, but that does not stop them from engaging in these criminal acts. Zwi et al. (2017) explain that some of these youths use crime as a way of expressing their frustrations to the members of the public. They believe that society should and will understand them when they engage in such illegal practices.

Theoretical Perspective

It is necessary to review various theories that can help in understanding youth offending. Theoretical perspectives on identity formation and the agency to change were some of the areas of focus (Hannibal and Mountford, 2019). Erikson’s theory of identity explicitly explains the stages of development and identity conflicts that one goes through in life. People often go through varying conflicts in these stages of life as they try to answer questions such as ‘who am I’, ‘what can I become’, ‘what is my role in society’ and ‘how can I interact with others’ (Eruyar, Huemer and Vostanis, 2018). People respond differently to these questions and they eventually define their personality.

Theoretical perspectives explaining youth offending can also help in understanding the problem. Operant conditioning is one of the theories that can be used to explain why some youths engage in criminal activities. According to Andriukaitienė et al. (2017), the theory holds that people tend to embrace a given behavior when it is associated with crime and punishment. A child who grows up in a neighborhood where crime is rampant is likely to engage in crime when they see it as rewarding (Baroudi and Arulraj, 2019). They admire the rich drug lords in society and embrace the idea that as long as one stays a step ahead of the law enforcement agencies, crime pays well.

Summary

It is important to identify conclusions that can be drawn from the above analysis about themes that are central to practice. The review of the literature shows that youth offending is still a major problem in the country. A significant population of these young offenders is in the country as asylum seekers. The government needs to find effective ways of dealing with the problem. The justice department and the law enforcement agencies should work closely to ensure that crime is prevented before it occurs. Creating a close working relationship with the entire society will eliminate the feeling that some people are discriminated against. It will promote a sense of responsibility among the entire population.

Application of the Principal Themes to Understanding and Developing Good Practice

The critical analysis conducted in the previous section has outlined the nature and magnitude of youth offending in the country. There is a need for various stakeholders to work as a unit to ensure that the problem is addressed in the most effective way possible to ensure that youths are protected. Based on principle themes discussed above, this section discusses how to promote good practice to ensure that children grow to become responsible and law-abiding youths and young adults. These themes can be applied in the following ways to help fight youth offending in the country.

Needs of Young Offenders

When addressing the problem, it is important to start by understanding the needs of young offenders. According to Bennett and Murakami (2016), one of the greatest needs of these delinquents is societal understanding, love, and support. Most of them feel rejected by society, making it easy for them to join criminal gangs and extremist groups (Bowers, Rosch and Collier, 2016). If they get the love and support from the immediate community, they can transform into responsible citizens. Youths need to be offered a platform for them to continue with schooling. The government should also create avenues where they can get actively involved in the economic development of the nation soon after leaving school (Farrington, Kazemian and Piquero, 2019). Such active participation in either the private or public sector limits the time and likelihood of them joining criminal gangs. These young offenders also need counselling and emotional support.

Crucial Points of Intervention in a Child’s Or Young Person’s Life

It is crucial to intervene at specific stages of a child’s development to ensure that they grow up into responsible young adults. The first stage is toddlerhood where a child learns very fast from the immediate environment (Calk and Patrick, 2017). They need to be shown love, respect, and compassion for them to reflect the same. The pre-adolescent age is another crucial point of development of a child where an intervention is needed (Hardwick, 2020). The child needs to learn personal restraint and the need to respect others and their property, just as they would want the same from others. The early and mid-adolescence stages are the most critical stages of development where one’s character is defined (Horner, 2019). They have fully developed abstract reasoning and can separate right from wrong. However, they still need the support, love, care, and guidance of members of society to become responsible adults.

Values, Principles and Skills of Good Practice for Young Offenders

Young offenders need to learn values, principles, and skills of good practice that can transform them into law-abiding citizens. As Cascio and Boudreau (2016) observe, in most cases, these individuals often commit the crime knowing that what they are doing is wrong. They need to embrace morality as a guiding principle in their lives. They need to avoid deliberate engagement in crime. They also need to gain practical skills that can enable them to earn a living in a legal way (Fox, Lane and Turner, 2018). They also need to understand their role in promoting a crime-free and progressive society.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Targeting Children and Young People at Risk of Offending

Targeting young people at risk of offending with effective programs is advantageous in various ways. At this stage, one can easily reform and become responsible citizens (Zhu and Kindarto, 2016). They are still full of hope and expectation and can easily embrace a legal path to success. When young people are targeted, the vicious cycle of crime is broken, creating a new generation that is focused and determined to lead crime-free lives. It also connects with work on identity formation as they embrace the need to become responsible citizens. Security agents and the rest of society can connect with the emerging responsible adult, rather than solely reacting to the angry adolescent (Fox, Lane and Turner, 2018). They will understand the assistance that these young people need to become responsible citizens. The major disadvantage is that the strategy may create an impression that older persons cannot change.

Limitations of the Intervention Strategies

There are limitations of intervention and strategies needed to work ethically within the social policy framework when dealing with the problem of youth offending. One of the biggest limitations is the lack of trust between the government and a section of society (Yang, Ding and Lo, 2016). Rolling out such a program in black-dominated neighbourhood may be viewed as an indication that the government considers them as more susceptible to crime. Instead of being viewed as a beneficial program, some will view it as a discriminative act against the minority. It would result in the lack of support (Chau and Liu, 2019). Lack of commitment from members of society who should be playing a major role in addressing the problem is another major limitation to the intervention strategies.

Effects of Gaps in Funding, Provision and Support Services

Gaps in funding, provisions, and support services have had a major negative effect on the fight against child offending in the country. According to Cherry and Aloisi (2016), various programs are needed to ensure that adolescents are assisted in becoming responsible citizens. However, such programs need funding, provisions, and other support services. They should be executed in learning institutions. The problem is that such programs are always not regular because of limited resources. In most of these cases, the programs are funded by the government (Yahaya, 2016). Private sector players are yet to get actively involved in funding such initiatives.

Obstacles to Effective Practice of Structural Inequality and Examples of Good Practice

Addressing the problem of youth offending will need stakeholders to understand obstacles to the effective practice of structural inequality and examples of good practice. As explained in the section above, the primary cause of structural inequality is capitalism (Wattsa, Steeleb and Mumford, 2019). However, it has proven to be the most practical economic ideology of all that currently exists and may not be easily changed. However, factors such as systemic racism, favouritism of a section of society, unfair tax policies that oppress the poor, and substandard education for the poor have been identified as major obstacles to the effective elimination of inequality (Verhezen, 2019). They need to be addressed to ensure that inequality is reduced. Good practices such as corporate social responsibilities focusing on empowering the youth should be encouraged among leading companies in the country.

Conclusion

The normal development and mental wellbeing of a child depend on the stability of the immediate family and the sociological support of society. Children who grow up in unstable families and social settings may easily become delinquents, as shown in sections one and two of this paper. A good example examined in the study is the refugees forced to leave their home country to foreign nations because of various factors. When these refugees get integrated into the new communities, their children’s holistic development and mental wellbeing will be protected. However, societal views on refugees are changing negatively as some of them are blamed for crime and terror. It means that these children may lack the needed holistic development and mental wellbeing. They are likely to become delinquents, engaging in various forms of criminal activities.

It is the responsibility of the government and all members of society to help fight the problem of juvenile delinquency. The number of youths engaging in various forms of crime is increasing, which is a major cause of concern. A significant number of these young offenders are from financially-challenged families in the country, which is an indication that poverty plays a critical role in promoting crime in society. Identifying all these factors responsible for promoting juvenile delinquency, including racism, is the first step towards solving the problem. Society should then work as a unit in addressing these problems.

References

Abouarab, J. (2019) Reframing Syrian refugee insecurity through a feminist lens: the case of Lebanon. New York, NY: Rowman & Littlefield.

Albanese, F. & Takkenberg, L. (2020) Palestinian refugees in international law (2nd edn). Oxford University Press.

Andriukaitienė, R. et al. (2017) ‘Theoretical insights into expression of leadership competencies in the process of management’, Problems and Perspectives in Management, 15(11), pp. 220-226.

Annamalai, A. (ed.) (2020) Refugee health care: an essential medical guide (2nd edn.). Cham: Springer Nature.

Baroudi, S. and Arulraj, D. (2019) ‘Nurturing female leadership skills through peer mentoring role: a study among undergraduate students in the United Arab Emirates’, Higher Education Quarterly, 7(1), pp. 1-17.

Bennett, H. and Murakami, J. (2016). After dark. London: Hodder Headline Limited.

Bhabha, J., Kanics, J. and Senovilla, D. (2018) Research handbook on child migration. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Blaemire, R. (2019) Birch Bayh: making a difference. Bloomington: Indiana University Press

Bowers, J., Rosch, D. and Collier, A. (2016) ‘Examining the relationship between role models and leadership growth during the transition to adulthood’, Journal of Adolescent Research, 1(5), pp. 1-23.

Bradley, M., Milner, J. & Peruniak, B. (eds.) (2019) Refugees’ roles in resolving displacement and building peace: beyond beneficiaries. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Brown, D. (2019) The unwanted: stories of the Syrian refugees. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Calk, R. and Patrick, A. (2017) ‘Millennials through the looking glass: workplace motivating factors’, The Journal of Business Inquiry, 16(2), pp. 131-139.

Cascio, F. and Boudreau, J. (2016) ‘The search for global competence: from international HR to talent management’, Journal of World Business, 75(1), 1-12.

Chase, E. (2020). Youth migration and the politics of wellbeing: Stories of life in transition. London: Ingram Publisher Services.

Chau, S. and Liu, J. (2019) ‘Proliferation and propagation of breakthrough performance management theories and praxes’, International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 68(4), pp. 1-192.

Cherry, M. and Aloisi, A. (2016) ‘Dependent contractors in the gig economy: a comparative approach’, Americal UL Review, 66(1), p. 635.

Cimatti, B. (2016) ‘Definition, development, assessment of soft skills and their role for the quality of organizations and enterprises’, International Journal for Quality Research, 10(1), pp. 97-130.

Cox, A. (2018) Trapped in a vice: the consequences of confinement for young people. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Croegaert, A. (2020) Bosnian refugees in Chicago: gender, performance, and post-war economies. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

Dapin, M. (2020). Public enemies: Russell ‘Mad Dog’ Cox, Ray Denning and the golden age of armed robbery. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

Diemer, M. (2016) More inclusive asylum policies in Germany? Norbert Elias and the tolerated refugees. Berlin: GRIN Verlag.

Digital social work: tools for practice with individuals, organizations. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Elliott, T. and Earl, J. (2018) ‘Organizing the next generation: youth engagement with activism inside and outside of organizations’, Social Media and Society, 4(1), pp. 1-14.

Elrod, P. and Ryder, R. (2021) Juvenile justice: a social, historical and legal perspective. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Eruyar, S., Huemer, J. and Vostanis, P. (2018) ‘How should child mental health services respond to the refugee crisis’, Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 23(4), pp. 303-312.

Farrington, D. P., Kazemian, L. and Piquero, A. (eds.) (2019) The Oxford handbook of developmental and life-course criminology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Fazel, M. and Betancourt, T. (2018) ‘Preventive mental health interventions for refugee children and adolescents in high-income settings’, The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 2(2), pp. 121-132.

Fazel, M. and Stein, A. (2002) ‘The mental health of refugee children’, Archives of Disease in Childhood, 87(5), pp. 366-370.

Fernández-Aráoz, C., Roscoe, A. and Aramaki, K. (2017) ‘Turning potential into success: the missing link in leadership development’, Harvard Business Review, 17(1), pp. 1-17.

Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, E. (ed.) (2020) Refuge in a moving world: tracing refugee and migrant journeys across disciplines. London: UCL Press.

Fox, A., Lane, J. and Turner, S. (2018) Encountering correctional populations: a practical guide for researchers. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

Garst, B. et al. (2019) ‘Fostering youth leader credibility: professional, organizational, and community impacts associated with completion of an online master’s degree in youth development leadership’, Children and Youth Services Review, 96(9), pp. 1-9.

Girma, S. (2016) ‘The relationship between leadership style, job satisfaction and culture of the organization’, International Journal of Applied Research, 2(4), pp. 35-45

Goldkind, L., Wolf, L. and Freddolino, P. (2018). Goularas, G., İpek, T. and Önel, E., (eds.) (2020) Refugee crises and migration policies: from local to global. New York, NY: Rowman & Littlefield.

Hannibal, M. and Mountford, L. (2019) Criminal litigation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hardwick, R. (2020). Pedophile hunters. New York, NY: Routledge.

Henry, D. (2020) Young refugees and asylum seekers: the truth about Britain. St Albans: Critical Publishing.

Hodes, M. and Vostanis, P. (2019) ‘Practitioner Review: Mental health problems of refugee children and adolescents and their management’, Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60(7), pp. 716-731.

Horner, N. (2019) What is social work: contexts and perspectives. London: Learning Matters.

Houwer, R. (2016) Changing leaders, leading change: a leadership development model for marginalized youth in urban communities. London: Youth Research and Evaluation eXchange.

Hunt, T. and Fedynich, L. (2019) ‘Leadership: past, present, and future, an evolution of an idea’, Journal of Arts and Humanities, 8(2), pp. 22-26.

Irop, I. and Kryvovyazyuk, I. (2018) ‘Transformation of entrepreneurial leadership in the 21st century: prospects for the future’, Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, 217(1), pp. 115-119.

Jansen, J. and Lässig, S. (eds.) (2020) Refugee crises, 1945-2000. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Juss, S. (2019) Research handbook on international refugee law. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Kane, B. et al. (2018) Universe illustrated by Neal Adams. Washington, DC: DC Comics.

Karagianni, D. and Montgomery, J. (2018) ‘Developing leadership skills among adolescents and young adults: a review of leadership programmers’, International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 23(1), pp. 86-98.

Kehnscherper, L. (2017) Agreement vs. deal: framing of the EU-Turkey refugee policy in German quality newspaper. Berlin: GRIN Verlag.

Kidman, F. (2018) This mortal boy. Auckland: Vintage.

Kostouros, P., and Thompson, B. (2018) Child and youth mental health in Canada: cases from front-line settings. Toronto: Canadian Scholars.

Kratcoski, C. and Edelbacher, M. (2018) Fraud and corruption: major types, prevention, and control. Cham: Springer.

Louis, K. and Murphy, J. (2017) ‘Trust, caring and organizational learning: the leader’s role’, Journal of Educational Administration, 55(1), pp. 103-126.

Madziva, R. and Thondhlana, J. (2017) ‘Provision of quality education in the context of Syrian refugee children in the UK: opportunities and challenges’, Journal of Comparative and International Education, 47(6), pp. 942-961.

Mathias, M. (2017) ‘Leadership development in governments of the United Arab Emirates: re-framing a wicked problem’, Teaching Public Administration, 35(2), pp. 157-172.

Mayfield, M., Mayfield, J. and Wheeler, C. (2016) ‘Talent development for top leaders: three HR initiatives for competitive advantage’, Human Resource Management International Digest, 24(6), pp. 4-7.

McGee, T. (2020) From Syria to Europe: experiences of stateless Kurds and Palestinian refugees from Syria seeking protection in Europe. London: Institute on Statelessness and Inclusion.

McKibbin, W. and Fernando, R (2020) The global macroeconomic impacts of COVID-19: seven scenarios. Melbourne: Australian National University and Centre of Excellence in Population Ageing Research.

Megele, C., Simpson, J. and Buzzi, P. (2017) Social media and social work: implications and opportunities for practice. London: Policy Practice.

Melde, C. and Weerman, F. (2020) Gangs in the era of internet and social media. Cham: Springer.

Meleady, R. and Crisp, J. (2017) ‘Take it to the top: imagined interactions with leaders elevate organizational identification’, The Leadership Quarterly, 28(1), pp. 621-638.

Mills, A. and Kendall, K. (eds.) (2018) Mental health in prisons: critical perspectives on treatment and confinement. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ministry of Justice. (2017) National offender management service annual offender equalities report: Ministry of Justice statistics bulletin. London: Ministry of Justice.

Mishra, N., Lama, D. and Pal, Y. (2016) ‘Human resource predictive analytics (HRPA) for HR management in organizations’, International Journal of Scientific & Technology Research Volume, 5(5), pp. 33-35.

Mumford, M. et al. (2017). ‘Cognitive skills and leadership performance: the nine critical skills’, The Leadership Quarterly, 28(7), pp. 24-39.

O’Neill, M. (2019) Police community support officers: cultures and identities within pluralized policing. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Parekh, S. (2020) No refuge: ethics and the global refugee crisis. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Park, E., Burgess, E. and Sampson, J. (2019) The city. London: The University of Chicago Press.

Patel, J., Poston, R. and Dhaliwal, J. (2017) ‘A workaround model for competent project managers using agile development in a traditional organization’, ICIS Proceedings, 9(1), pp. 1-13.

Pretorius, S., Steyn, H. and Bond-Barnard, T. (2018) ‘Leadership styles in projects: current trends and future opportunities’, South African Journal of Industrial Engineering, 29(3), pp. 161-172.

Pycroft, A. and Gough, D. (eds.) (2019) Multi-agency working in criminal justice: theory, policy and practice. Chicago, IL: Policy Press.

Rathore, V. (2019) An insight into Indian juvenile justice system. New Delhi: Notion Press.

Reynolds, D. and Bacon, R. (2018) ‘Interventions supporting the social integration of refugee children and youth in school communities: a review of the literature’, Advances in Social Work, 18(3), pp. 745-766.

Rioli, C. (2020) A liminal church: refugees, conversions and the Latin diocese of Jerusalem, 1946-1956. Leiden: BRILL.

Rothblum, D. (ed.) (2020) The Oxford handbook of sexual and gender minority mental health. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Samara, M. et al. (2020) ‘Examining the psychological well‐being of refugee children and the role of friendship and bullying’, British Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(2), pp. 301-329.

Schnyder, M. and Shawki, N. (2020) Advocating for refugees in the European Union: norm-based strategies by civil society organizations. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

Sciaccaluga, G. (2020) International law and the protection of climate refugees. Cham: Springer Nature.

Shaikh, M., Bean, C. and Forneris, T. (2019) ‘Youth leadership development in the start to finish running & reading club’, Research Gate, 14(1), pp. 112-126.

Shamira, B. and Eilam-Shamir, G. (2017) ‘Reflections on leadership, authority, and lessons learned’, The Leadership Quarterly, 28(1), pp. 578-583.

Sherif, V. (2018) ‘Voices that matter: rural youth on leadership’, Research in Educational Administration & Leadership, 3(2), pp. 311-337.

Skorková, Z. (2016) ‘3rd international conference on new challenges in management and organization: organization and leadership in Dubai, UAE, competency models in public sector’, Social and Behavioral Sciences, 230(6), pp. 226-234.

Song, J. and Song, T. (2019) Big data analysis using machine learning for social scientists and criminologists. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Stariņeca, O. (2016) ‘Employer brand role in HR recruitment and selection’, Economics and Business, 1(58), pp. 58-62.

Strielkowski, W. and Chigisheva, O. (2018) ‘Leadership for the future sustainable development of business and education 2017 Prague institute for qualification enhancement (PRIZK) and international research Centre (IRC) scientific cooperation international conference’, Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics, 4(1), pp. 69-75.

Suddler, C. (2020) Presumed criminal: black youth and the justice system in postwar New York. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Teller, A. (2020) Rescue the surviving souls: the great Jewish refugee crisis of the seventeenth century. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Thompson, E., and Thompson, L. (2020) Sociological wisdom. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Thompson, E., Bynum, J. and Thompson, M. (2021) Juvenile delinquency: a sociological perspective. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Tu, Y. and Lu, X. (2016) ‘Do ethical leaders give followers the confidence to go the extra mile: the moderating role of intrinsic motivation’, Journal of Business Ethics, 135(1), pp. 129-144.

Úcar, X., Soler-Masó, P. and Planas-llad, A. (2020) Working with young people: a social pedagogy perspective from Europe and Latin. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Van, H. and Bourke, M. (2017) Handbook of behavioral criminology. Cham: Springer.

Verhezen, P. (2019) ‘Leadership wise leadership and AI why new intelligence will need new leadership’, Research Gate, 3(1), pp. 1-25.

Wang, J. (2018) Carceral capitalism. Cambridge, MA: Distributed by the MIT Press.

Wattsa, L., Steeleb, M. and Mumford, D. (2019) ‘Making sense of pragmatic and charismatic leadership stories: effects on vision formation’, The Leadership Quarterly, 30(9), pp. 243-259.

Weiwei, A. (2020) Human flow: stories from the global refugee crisis. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Yahaya, R. (2016) ‘Leadership styles and organizational commitment: literature review. Journal of Management Development, 35(2), pp. 190-216.

Yang, C., Ding, G. and Lo, K. (2016) ‘Ethical leadership and multidimensional organizational citizenship behaviors: the mediating effects of self-efficacy, respect, and leader–member exchange’, Group & Organization Management, 41(3), pp. 343-374.

Zhu, Y. and Kindarto, A. (2016) ‘A garbage can model of government IT project failures in developing countries: the effects of leadership, decision structure and team competence’, Government Information Quarterly, 4(1), pp. 1-8.

Zwi, K. et al. (2017) ‘Refugee children and their health, development, and well‐being over the first year of settlement: a longitudinal study’, Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 53(9), pp. 841-849.