Introduction

Besides modern-day business and distributed learning, telemedicine is all poised to be the next big beneficiary of the wonders and advancements in the field of telecommunication and digital technology. Technological innovations facilitated the development of sophisticated medical equipment and systems on one hand and also reduced geographical barriers on the other, enabling collaboration and transfer of expertise, knowledge, and ideas between medical experts from different locations. Today, expert physicians can even supervise & execute surgery, i.e., telesurgery, on patients physically staying far away. So, a patient from one country may seek treatment from a doctor of a different country or region and thus, telemedicine is expected to be a good form of trade. However, the telemedicine trade is not much overwhelming as of now and it is concentrated in some of the developed countries only.

Taking on from here, this chapter proceeds to take stock of the present situation and assess how telemedicine has evolved as a trade-in in recent times especially considering today’s unprecedented developments in the field of information technology and e-commerce.

Telemedicine-Scopes & Dimensions

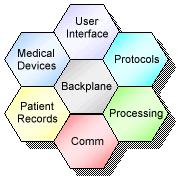

Broadly speaking, telemedicine is an umbrella term encompassing various technologies as part of a coherent health-service information resource management program (JMS, 1995). Telemedicine involves providing patient care and medical diagnostics services at a distant site away from the service provider with the aid of telecommunication technology. Telemedicine has technological diversity as shown in Figure-1.1 and the main involvements here are capture, display, storage, and retrieval of medical images and data thereby creating a computerized patient record. The telecommunication aids generally used for telemedicine include everything from standard telephone service, high-speed connections, and wide bandwidth transmission of digitized signals to computers, fiber optics, satellites, and other sophisticated peripherals (NASA, 2007).

Telemedicine is not a new concept; it has been around for the last 25-30 years. Marking the first step towards telemedicine, doctors, long back, started exchanging opinions over the telephone and fax regarding the appropriateness and accuracy of medical examination and treatment geographically remaining in different places or locations (Pachanee & Wibulpolprasert, 2004).

This practice intensified following the progress on the Internet and the mobile networks and this lead to an increase in data exchange with more accurate imaging and patient records. Telemedicine can be segmented into three segments- aids to decision-making, remote sensing, and collaborative arrangements for the real-time management of patients at a distance (WHO, 2001). The oldest aspect of telemedicine is its utility in decision-making followed by transmission of patient information like x-rays, electrocardiographs, patient history, etc. from a remote site to the patient’s location in a different place or site. Further, telemedicine can also contribute to the collaboration of ideas and skills between two practitioners for a patient far away from both of them. This collaboration raises important issues of referral and payment arrangements, staff credentialing, liability, and licensure potentially crossing local jurisdictions.

Telemedicine or telehealth seems to be intrinsically a dynamic and collaborative process and the low-cost services it can bring in against the barriers of space and time and the opportunities it provides for a meeting of the minds & collaboration of the best medical brains of the world in a non-contact manner makes telemedicine an automatic option (WHO, 2001) particularly for the less-developed countries to leverage on.

Evolution of Telemedicine

At least three overlapping generations of telemedicine evolution can be traced back since its inception some 30 years ago. The first generation includes the synchronous and asynchronous, the 2nd generation data storage and transfer, and the 3rd generation automated decision-making & application of advanced robotics (Whitten, 2004). These three stages of telemedicine progress have a strong bearing on the developments in the field of information technology and telecommunications (ICTs). The synchronous stage saw approaches like Real-time Video conferencing, Telepsychiatry, Telehospice (Whitten, 2004). The asynchronous includes the store & forward concepts like Teleradiology (sending X-rays, CT scans, etc.), Telepathology, and Teledermatology. The 2nd generation shifts started in the 1990s when the focus on information content replaced preoccupation with the timing of the health interaction. During that period, data storage and transfer systems like the Electronic Medical Record (EMR) integrated with video-conferencing, EMR based Picture Archiving System (PACs) and other Decision Support Tools (DSSs) tools enabling human judgment emerged (See, Pallawala & Lun, 2001; Ratib et al., 2003). The utility of DSS has been well recognized and soon followed further developments adding value to the DSSs by integrating with robotic technology that market the beginning of the 3rd generation Robotics integrated Decision Support System (UNCTAD, 1998).

The other widely used technology, two-way interactive television (IATV), is used when a ‘face-to-face’ consultation is necessary. The patient and sometimes their provider, or more commonly a nurse practitioner or telemedicine coordinator (or any combination of the three), are at the originating site. The specialist is at the referral site, most often at an urban medical center. Videoconferencing equipment at both locations allows a ‘real-time’ consultation to take place. The technology has decreased in price and complexity over the past five years, and many programs now use desktop videoconferencing systems. There are many configurations of interactive consultation, but most typically it is from an urban-to-rural location. It means that the patient does not have to travel to an urban area to see a specialist, and in many cases, provides access to specialty care when none has been available previously. Almost all specialties of medicine are conducive to this kind of consultation, including psychiatry, internal medicine, rehabilitation, cardiology, pediatrics, obstetrics and gynecology, and neurology. Many peripheral devices can be attached to computers that can aid in an interactive examination.

Many health care professionals involved in telemedicine are becoming increasingly creative with available technology. For instance, it’s not unusual to use store-and-forward, interactive, audio, and video still images in a variety of combinations and applications. The use of the Web to transfer clinical information and data is also becoming more prevalent. Wireless technology is being used for instance, in ambulances providing mobile telemedicine services.

Barriers to Telemedicine

Even today telemedicine faces some barriers limiting its all-out adoption. Insurance happens to be a problem in the case of telemedicine as private insurers are not interested in reimbursements for such treatments (VanderWerf, 2004). Physicians are also reported to have fear of getting linked to any malpractice suits. The also runs an impression that telemedicine is a very sophisticated, complex, and expansive form of treatment and this is also hampering progress. Another unfortunate fact is that most of the solutions and telemedicine techniques are proprietary items discouraging easy sharing of solutions and resources.

References

(JMS) Journal of Medical Systems, A quick guide into the world telemedicine. 1995, 19/1.

NASA Telemedicine Technology Gateway. 2007. Web.

Pachanee Cha-aim & Wibulpolprasert Suwit “Dual Track Health Policies: In-coherence between the Policy on Universal Coverage of Health Insurance and the Policy on Trade in Health Services in Thailand”, Global Forum for Health Research, Mexico City, 2004.

WHO (Department of Health and Development), Background note on “Assessment of Trade in Health Services and Gats”, 2001.

Whitten Pamela, “Telehealth: Evolution rather than Revolution”, Professor and Faculty Scholar, Regenstrief Center for Healthcare Engineering, 2004.

(UNCTAD)/United Nations Conference on Trade and Development and World Health Organization (WHO), “International Trade in Health Services: A Development Perspective”, 1998, (UNCTAD/ITCD/TSB/5).

VanderWerf Mark, “Evolution of Telemedicine Technology”, AMD Telemedicine, 2004.

UNCTAD-WHO Joint Publication on “International Trade in Health Services- A Development Perspective, Geneva, 1998.

World Health Organization, “The Geneva Briefing Book UNOG and the UN Specialized Agencies”, 2003.

Abelin Theo & the Policy Committee of the WFPHA, “Health and International Trade Agreements Proposed by the Public Health Association of Australia (PHAA)”, 2004.

Kickbusch Ilona, “The World Health Organization: Some Governance Challenges”, Yale University, Bellagio Study and Conference Center, 2000.

(WHO) Statement of the World Health Organization on International Trade & Health, at the World Trade Organization Ministerial Conference, Hong Kong, 2005.

(UNCTD)/United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, “International Trade In Health Services: Difficulties And Opportunities For Developing Countries”, Background note by the UNCTAD Secretariat, TD/B/COM.1/EM.1/2, 1997.

Marzolf R. James, “The Indonesia Private Health Sector: Opportunities for Reform- An Analysis of Obstacles and Constraints to Growth”, World Bank Consultant, 2002.

WFPHA position paper on “International Trade Agreements: Priorities for Health”, World Federation of Public Health Associations, Washington DC, 2003.

Fidler P. David & et al., “Legal Review of the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) from a Health Policy Perspective”, The World Health Organization, 2005.

Wibulpolprasert S, Jindawatthana A, Hempisut P, “General agreements on trade in services and its possible implications on the development of human resources for health”, Paper presented in the Annual Meeting of the American Public Health Association (APHA), Boston 2000.