Abstract

The Euro crisis is an economic crisis that not only points at the weaknesses of economic integration, but also points at the consequences of poor economic policies at the state level. The aim of this paper is to synthesise literature on the causes, progression, and impacts of the Euro crisis on the European economy.

The literature shows that the Euro crisis is far from over. The European countries have to rethink about the economic integration strategies that can encourage prudent management of individual economies in the region to avoid such shocks.

Introduction

The Euro crisis was seen not only as a financial problem in the European Union countries, extending from the global financial crisis, but also as a real test of the essence of economic integration. The European Union has come out as a benchmark of economic integration in the whole world.

The rationale behind the terming of the European Union as a global benchmark when it comes to matters of economic cooperation and unity among states in the region is that it is the only economic union that has managed to realise the workability of a common currency.

However, as mentioned in the opening sentence, the Euro crisis, whose genesis lies in the debt crises that mounted in a number of countries that form the monetary union, namely Greece, Spain, Ireland, and Italy, among others, resulted in the replication of the problem across the European Union.

A substantial number of economic commentators term the Euro crisis as a problem that denoted the difficulty of integrating individual economies and dealing with economic pressures that come from the attributes of economic management in individual economies.

The interesting thing about the crisis is that it serves as an example of how problematic economic integration can become because the faulty actions of other players could pose grave economic consequences requiring major economic decisions and adjustments by the individual states to solve the problem.

This paper presents a review of literature on the Euro crisis and its impacts on Europe and the entire global economy. The paper contacts three main research databases, namely EBSCOHost, SIRS Researcher, and ProQuest.

These three databases play a critical role in presenting sequential information regarding the moulding of the Euro crisis and the consequences of the Euro crisis in terms of economic policy development and the performance of the economy, more so on the affected economies.

The selection of articles from EBSCOHost is based on topic search, where preference is given to different articles denoting diverse dimensions of research about the Euro crisis. Most of the articles derived from the SIRS Researcher database point at the fact that the Wall Street Journal receives more attention because most articles in this database are those published by the Wall Street Journal.

This is aimed at producing data that is consistent concerning the development of the crisis as understood by the researchers who write for the Wall Street Journal. The articles selected from the ProQuest database depict information about the Euro crisis based on the external views about the effects of the crisis beyond the European Union borders.

The genesis of the Euro crisis

A substantial number of economic commentators agree with the observation that the Euro crisis, which is also referred to as the sovereign debt crisis, was brought about by the significant deficits in the balance of payments of individual countries due to unsustainable fiscal policies pursued by these countries over a substantial number of years.

Higgins and Klitgaard (2014) argue that the Euro crisis begun from the fiscal problem in Greece due to the accumulation of debt by Greece. Higgins and Klitgaard (2014) further note that Greece and other periphery economies in the European Union relied heavily on external capital. These countries needed the capital to finance housing booms and domestic consumption.

The only option that seemed feasible to them was to borrow from other countries, given they could not afford to source the finances locally. Wood (2012) observes that the European countries, especially the countries in south Europe, failed to agree on a common framework on which they could opt for the Euro as a common currency.

At this point, Germany gets a fair share of the blame for failing to exercise a leading role and, instead, taking a fiscal strategy that plunged the other southern Europe economies into debt (Wood 2012).

Milios and Sotiropoulos (2010) ascertain the essence of looking at the Euro crisis from the perspective of the cycles of capitalism in the Eurozone, rather than pointing fingers at the debt crisis in Greece. The real value of economic integration lies in the kind of strategies that are taken by countries forming the economic block to offset the deficits in the balance of payments.

In this case, the crisis in the Eurozone is a problem that cannot be directed at one country, but the failure should also be associated with the other countries that had a chance to salvage the debt problem in the region. However, they failed to do so due to their own reasons.

The high rate of indebtedness in Greece depicts not only the weakness of economic governance in Greece, but also the failure of Germany as a key player in the region to activate some steps that could salvage Greece and the entire region at large (Dinan 2012).

Rosenthal (2010) further observes that the deficit limit that was set by the European Union was not only exceeded by Greece, but also other players in the European Union like France. The main concern here is that the European Union did not sanction France because of political malice.

The rationale here is that France is a big brother in the European Union; that is why it is favoured even when it breaches the set standards of the EU monetary union (Rosenthal 2012). The figure below could serve as an indicator of the manipulation of the economies of the region by Germany due to the introduction of the Euro as a common currency in 2002.

Figure 1.0 denotes a significant rise in Germany’s current account balance after the introduction of the Euro as a common currency in 2002.

The non-existence of an exchange-rate buffer prior to the introduction of the Euro as a common currency led other weak economies in the region to lose their competitiveness as Germany took advantage of its manufacturing and export power to deny other countries the opportunity to thrive in the market.

This indicates a kind of economic exploitation of other countries, a factor that necessitated the increase in the amount of foreign debt (Rosenthal 2012). Baimbridge, Burkitt and Whyman (2012) ascertained that the deflation that was later experienced in other countries in the Eurozone was as a result of the creation of a boom-bust cycle emanating from the implementation of a similar interest rate for all countries.

As the most powerful economy in southern Europe, Germany could easily adjust its taxation regime to compete at a fairly lower exchange rate. This could play a critical role in reducing the financial burden in other Eurozone countries. For more information about the comparative aspects of foreign current account balance in the European Union, see figure 1 and figure 2 in the appendix.

Higgins and Klitgaard (2014) observed that dependence on borrowed money often results in its risks, particularly in situations where the countries from which the money is borrowed are no longer in an economic position to offer credit. Higgins and Klitgaard (2014) base this assumption on the issues of saving and investment at the domestic level.

They note that reliance on borrowing and the failure to invest the money in economic segments that can spur local investment and savings, just as in the case of Greece and other countries in the European Union, often results in economic problems.

A broader look at the Euro crisis by Wood (2012) reveals a number of causative factors. Among these factors are imprudent banks, errors in economic policy development and implementation, remote technocracy, lack of effective regulation, and turbo-capitalism. These factors are, in one way or another, linked to the mounting of the debts in individual countries across the European Union.

However, Wood (2012) further observes that the Euro crisis is an economic crisis that cannot be only linked to the mounting debts in individual economies in Europe, but also a problem that can be understood by incorporating other attributes like history, sociological forces, and other elements of governance across Europe.

In other words, Wood (2012) moves away from the dominant view supported by a substantial number of researchers, who synthesise the Euro crisis only based on the debt question while failing to open up to other forces that might have resulted in the worsened economic situation in Europe.

Hall (2012) raises similar sentiments by noting that the Euro crisis presents a number of puzzles, as people seek for answers about the real causes of the crisis in what was earlier on applauded as a benchmark as far as economic integration in the world is concerned.

Hall also paints the picture of how the two hemispheres in Europe seem divided over the crisis, where the northern European countries blame the south by pointing at the fiscal faults inherent in the economic policies of southern Europe governments. Hall presents an important statistic about the Euro crisis.

The figure indicates significant variations in demand for growth, which means that the countries with a high percentage of domestic demand were under pressure to develop and enforce growth-oriented reforms.

As the country with the highest domestic demand, Greece had no other option that to be proactive in developing strategies that could help meet its skyrocketing domestic demand. Borrowing from the other countries with limited domestic demand was necessary to meet the domestic demand in Greece (Hall 2012).

Progression of the Euro crisis

A deeper look at the Euro crisis shows that the crisis moved from the debt problem in individual economies to the subsequent currency war. Rosenthal (2012) observes that the crisis in the Eurozone is best reflected in the difficulties that transpired in the operation of the monetary union.

The functioning of the union was threatened as it became apparent that the local currencies in individual economies were becoming weaker and the affected countries had little to do to limit the deficits in their balance of payments. A series of actions were taken as a way of seeking for a solution to the plummeting currency problem in the Eurozone.

Among these actions were the numerous currency devaluations to strike a balance between supply and demand. The setting in of the monetary union created a tough situation for currency speculation in the region. The extreme downward adjustment in the exchange rate meant that a further downward adjustment of the exchange rate would not be achieved (Rosenthal 2012).

Baimbridge, Burkitt and Whyman (2012) present another dimension to the Euro crisis, in which they focus on the creation of the Eurozone and the effects that come with its creation. Fiscal discipline is vital in the sustenance of a monetary union. The free-rider and spill-over effects as noted in the Euro crisis are perfect examples of the faults of fiscal policy in the management of a monetary union.

Thus, Baimbridge, Burkitt and Whyman (2012) summarize the Euro crisis by pointing at the prevalence of a number of structural weaknesses in the Eurozone. It is the structural weaknesses in the European Union that resulted in the escalation of the debt crisis from Greece to other countries in the Eurozone.

In their assessment of the mounting debt crisis in the Eurozone, Higgins and Klitgaard (2011) noted that the rates of borrowing in the Eurozone rose amidst the introduction of the common currency and the inability of individual countries to finance their domestic expenditures.

Higgins and Klitgaard (2011) also note the creation of an economic cycle of dependency in the European Union, where a number of countries in the region were left to become dependent on borrowed money. Higgins and Klitgaard (2011) also acknowledge the countermeasures taken by the affected countries, most of which entail the consolidation measures.

These measures are aimed at attaining a significant reduction in fiscal deficits in the required set standard of below 3 per cent. The measures to bring down the fiscal policies that are being implemented now could have been put in place earlier to prevent these countries from entering into debt crises, such as the one that culminated into the Euro crisis (Higgins & Klitgaard 2011).

A focus on the impacts of the Euro crisis based on the functioning of markets in the European Union and other countries that fall outside the European monetary and economic unions by Melander (2011) shows the heightened effects of the crisis beyond the assumptions made by the European Union.

This is notable in the observation made by Zuckerman (2011) and Francis (2012), who ascertain the essence of the countries beyond the European region to develop and implement economic measures that can cushion them from the crisis.

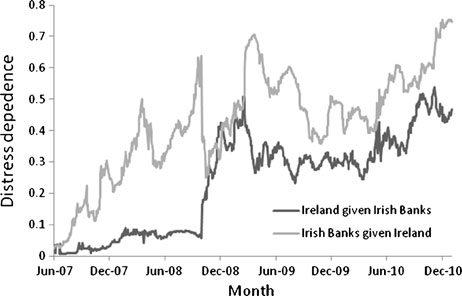

Malander (2011) paints the picture of the distress in countries where the Greek financial institutions were operating prior to the Euro crisis through the entire build-up of the crisis as shown in the figure below.

The common denominator of the figure is that the weaknesses portrayed in the economic systems of Greece were replicated in the financial institutions from Greece. The deepening of the distress in Greece over the years resulted in the deepening of the distress in other economies that had close links with Greece through the operation of Greek institutions in these countries.

It is also apparent that the exposure of the Greek economy in line with the weaknesses in other economies like the Irish economy also acted as an aggravating factor for the Euro crisis (Malander 2011). The same can also be said about the mounting of the debt crisis in Ireland as indicated in the figure below.

This expands on the reason why the Euro crisis comes is an intertwined economic problem that cannot not be sorted out easily by implementing unitary strategies. The approach taken by each individual country has a lot of effects on other countries in the European Union.

Zuckerman (2011) reports about the currency defaults across the European Union as a result of the low lending rates by the European Central Bank to countries in the European Union. Most banks were left with no option because of the growth in the amount of unnegotiated currency defaults.

There is no room for underestimation as the debt that has been accumulated by countries in the region, including Italy as the 8th largest economy in the world, is too huge. Italy is also ranked as a third largest bond market, but it remains unclear whether the $2.6 trillion sovereign debt accumulated by the country can be cleared any soon.

Zuckerman (2011) justifies the worry of the United States by observing that most of the affected countries in Europe continue to come up with austerity programs. However, these programs are risks in themselves as they deepen the recession in most cases, thereby making it even harder for the affected countries to service the huge debts.

The more these debts prevail, the more difficult it is to establish sustainable economic relations between the affected countries and other economies in the world. Also, the Euro as a common currency in the European Union faces major challenges, especially from people who link the crisis to the introduction of the Euro as a common currency in the Eurozone (Zuckerman 2011).

However, Brittan (2010) defends the Euro by observing that the Euro is not a problem per se. The problem in the Eurozone lies with the inconsistent and fragmented economic policies and strategies adopted by the countries in the Eurozone.

Saving the Euro is the priority of the European Union. Nonetheless, a look at individual countries, especially the economic powerhouses in the European Union like Britain, France and Germany, shows that these countries are committed to saving their financial institutions like banks from the risks associated with the Euro crisis (Farrell & Quiggin 2011).

Farrell and Quiggin (2011) further note that some countries like Germany have gone as far as developing laws to help induce debt brakes. Other countries in the Eurozone, totalling to sixteen, also followed a similar road.

However, most of the efforts initiated by players in the Euro crisis are short-term, raising questions about the possibility of developing long-term economic measures to prevent a debt problem from occurring again in the future. Farrell and Quiggin (2011) see the short-term strategies as necessary for limiting expenditure and ensuring that the bond markets across the Eurozone calm down.

After laying blame on Greece for the Euro crisis, most of the European countries agree that saving Greece is a key step in easing the economic pressure in the region.

The budget crisis in Greece was a subject of most European leaders in the onset of the Euro crisis, more so when the countries in the region realized that the budget problem in Greece was not only a problem of Greece, but also a problem of all other countries in the region (Forelle, Walker & Galloni 2010).

Impacts of the Euro crisis and the lessons learnt

Münchau (2013) observed that the Euro crisis is an example of smouldering crises that are born out of the lack of prudent systems of economic management in economic integration. Münchau cites what he refers to as the inflexible fiscal rules and compliance procedures that impeded the creation of incentives.

What happened is that the system of economic management that came immediately and after the introduction of a monetary union subjected the smaller economies in the region to tough economic measures, most of which could not be upheld by these states.

The application of the principles of economic management like the no bailout principle enshrined in Article 125 of the European Union Treaty is a justification of how difficult it is to solve problems of insolvency in individual economies that form the European Union.

Other cited difficulties include the “no default” and “no exit” principles, which limit the level at which liquidity support can be offered to European Union member countries in times of crises (Münchau 2013).

To this effect, Münchau reiterates the essence of intense coordination of policy, monetary, fiscal, national sovereignty, and regional and global policy to avoid a situation where the players in economic integration read from different pages.

Melander (2011) is quite pessimistic about the application of the principles of economic liberalization by states in the quest of states to conform to economic integration. Melander uses Ireland, one of the countries that exhibited the problem of mounting debt in the progression of the Euro crisis, by noting the fact that Ireland was applauded as a benchmark for flexibility and liberalization in the realms of economic integration.

The situation later changed when Ireland later plunged into a debt amidst the mounting economic pressure in the Eurozone. The progression of the crisis resulted in a situation where the benchmark countries in terms of economic liberalization like Ireland and the worst performing economies in the region like Greece ending up in the same capsizing boat (Melander 2011).

The other issue that comes out in Melander’s (2011) analysis of the Euro crisis is the fact that economic networks are potentially harmful, irrespective of the minute nature of the economic problems that occur in an individual country. Together, Greece and Ireland do not even amount to 5 percent of the GDP of the Eurozone, yet the debt crisis in the two countries posed a threat to the entire European Union economy.

Capital flow in trade and finance between member states in an economic union is an issue that warrants attention by individual states because individual states remain with the responsibility of supporting its institutions in times of economic downturn.

However, a look at the response to the debt crisis in Greek and other countries proved the inability of governments to support their financial institutions. Consequently, these financial institutions were rendered helpless in terms of boosting the domestic financial status of the economy of countries where they base their operations (Melander 2011).

Xafa (2010) explores the unavoidable questions about the role of the global financial institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in cushioning countries from the effects of the Euro crisis. The International Monetary Fund served as a key institution in raising alarm about the global financial crisis. Nonetheless, such an alarm could not easily work with the Euro crisis.

The Euro crisis required more than policy advice, especially for the countries that were already facing the economic effects of a huge foreign debt now that these emerging European economies could not access the externally funded credit from other countries. Irrespective of this, Xafa applauds the International Monetary Fund for its proactive steps of continuous surveillance of the global economy.

Failures that resulted in the worsening of the economic situation in the European Union are linked to the rigid commitments of individual countries, which make them stiff when it comes to matters of economic support and adjustment for the common good of other states (Xafa 2010).

Besides the issue of economic and financial regulation by international bodies like the International Monetary Fund is the issue of willingness of countries to go to the deeper ends in salvaging a monetary union. Karras (2011) contends with the fact that the introduction of the Euro as a common currency triggered the credit problem in the Eurozone, thus necessitating credit pressures across the Eurozone.

However, Karras also agrees with the findings made by a substantial number of economic researchers pointing at the fact that the economic decisions taken by individual countries at the early stages of the Euro crisis were highly disintegrated and could not promote a common solution.

The observation here can be linked to the opinions raised by a substantial number of economic commentators, who argue that the Euro crisis would result in losers and winners. Heisbourg (2012) indicates that the winners and losers in the economic turmoil depended on the economic and political paths pursued by individual countries.

The Euro crisis is a lesson to countries in the European Union, most of which have had to review their strategic economic choices. An example given here is the reliance of Germany on exports and the difficulty to sustain exports when the destiny countries face severe economic problems that inhibit their potential to import goods from Germany (Heisbourg 2012).

Since the beginning of the European sovereign debt crisis, the United States as one of the largest traders with the European Union has remained active in terms of making adjustments in its economy. Most, if not all the adjustments, are aimed at cushioning the country from the shrinks in trade and securing its financial system from fallout like the financial system of Europe (Francis 2012).

In the real sense, a direct exposure of the United States markets to the crisis in the European Union has not been established. However, a substantial number of investors in the United States share the sentiment that the United States’ market is vulnerable to the crisis in the Eurozone, especially when long-term solutions do not come from the European countries (Heisbourg 2012).

In his research about the export strength of Germany in the European Union amidst the crisis in the Eurozone, Foroohar (2011) found out that Germany export capacity depends on the internal economic strengths of a number of countries in the European Union, like Spain and Italy.

The reason why Germany finds itself at the centre of the Euro crisis is that it depends on the Eurozone for approximately half of its net exports (Foroohar 2011).

The financial woes in the Eurozone present a new basis on which the issue of regional economic integration should be reassessed. Walker and Galloni (2013) report on the thoughts raised about the benefits and risks associated with leaving and remaining in the European Union for countries that have been severely affected by the Euro crisis.

The opinion about leaving the Euro vary across Italy, where 74 per cent of the Italians feel that it is prudent for Italy to remain in the Euro while 20 per cent of Italians feel that leaving the Euro is an economic reprieve for Italy. However, most governments in the Eurozone remain consistent in support of the Euro, which makes Walker and Galloni (2013) to conclude that the Euro is meant to stay put.

Governments, on the other hand, are charged with the responsibility of ensuring that they keep implementing austerity measures even amidst opposition from a section of the European population. In other words, European countries face an economic situation that is a true test of whether they can maintain their solidarity and fight for the survival of the European economic bloc.

Most people remain keen to see the steps taken by individual economies in the Eurozone. Nonetheless, there is no window for disintegration even amidst what is seen as divergent tactics by individual countries as they develop mechanisms of preventing further shocks in their economies (“European union: Solidarity is under threat from crises” 2011).

The financial woes in the Eurozone, according to Dadush (2013), are quite far from being over because the risk of collapse of the bond markets in the Eurozone remains active.

The question of unemployment in the Eurozone rose to eighteen million unemployed people, even as more commentators predicted light at the end of the seeming endless tunnel for the countries in the Eurozone. However, Dadush (2013) faults the proclamation by European governments that the crisis in the European Union is nearing the end.

It would be illogical to explore the Euro crisis without mentioning the effects of the crisis on the industries in the affected countries. In their presentation of the effects of the crisis on the European economy, Walker and Galloni (2013) reported fears among a substantial number of workers, especially in plants that are directly affected by the major shrinks in the economy.

The example provided here is Mirafiori car-assembly plant, which has shed almost half of its employees since the beginning of the crisis. An assessment of the Greece economy by Kalafati (2012) revealed that the Greece economy was worst hit by the Euro crisis.

A focus on the health care sector of Greece depicts massive cuts in expenditure on health care. Even amidst the increase in tax to finance health care, the government of Greece still has not managed to prevent the layoffs in the sector (Kalafati 2012).

Salin (2012) is one of the commentators who are looking at the conflict in the Eurozone not only from the economic perspective, but also from the political perspective. Salin identifies some of the politically-inclined sentiments raised by governments in his assessment of the actions taken by governments to tackle the Euro crisis.

Among these sentiments is that the monetary system of the Euro ought to be unified with the national policies. This is termed as the centralization of the European Union.

This is a political move that can be used for maintaining a single currency use by the countries for economic benefits by ensuring that states do not only see the European Union as an economic stepping stone, but also maintain a system of checks and balances in their economic operations (Salin 2012).

Farrell and Quiggin (2011) note the European Central Bank has now gained more powers as a key institution of monitoring the monetary policy in the European Union. This implies the control of monetary policies in the region, thus countries in the region cannot merely rush to monetary policy options whenever they face tough economic situations like the increase in the size of sovereign debts.

Though opposed by a number of countries, a strong European Central Bank is necessary for supervising the big banks across the European economic bloc, besides ensuring that there is stability in the bond markets across the bloc (Walker & Steinhauser 2013).

Walker and Steinhauser (2013) assess the possibility of embracing a political union by the European Union countries. The authors ascertain the need for the political union to ensure desirable coordination of the economic policies. The signs inherent in the sentiments from a number of stakeholders show that a political union of the European Union countries is far from being realized.

As it is now, the European governments seem to be preoccupied with bolstering the currency union to prevent fiscal profligacy. The European countries have realized that the monetary union that they entered into is far from being accomplished as notable in the debt crisis that almost tore the Union apart (Walker & Steinhauser 2013).

Conclusion and recommendation

The review of the literature conducted in this paper shows that the Eurozone countries are subjected to a test on whether they can act in a manner that is consistent with the desire to keep the European Union intact. According to most researchers, there are a lot of gaps in the integration of the European Union. These can be summed into one question: Does the answer to the Euro crisis lie with integration or disintegration?

A substantial number of the opinions raised by economic commentators and political economists point at the fact that countries in the region have been contemplating on whether to embrace the Euro as a single currency or whether to shun the Euro and stick to their national currencies.

Even as the debate rages on whether to stick to the Euro or whether to shun the Euro, it is apparent that the countries are put between a rock and a hard place as the option to abandon the Euro could be more disastrous to economies in the region.

Moving forward, the European countries should review the framework under which the rules and policies of economic integration are developed and implemented. The vital thing here is that the European Union members should put their heads straight when developing these policies and rules.

This is aimed at making all the countries of the Union to abide by the rules because the failure to stick to the economic policies and rules is one reason why the Euro crisis came into being. European solidarity is important and should be reflected in the development of economic cooperation among countries in the Eurozone.

The issue of spendthrift governments cannot arise if each of the government remains committed to the rules and policies and if other governments in the European Union remain committed to supporting a worthy economic cause for all other partners in the European Union.

Prudent economic management is a vital element for each country in the European Union. As such, there is a need to look into this attribute. The Euro crisis finds its roots in the attributes of irresponsible fiscal and monetary policies by individual countries.

Whether the level of irresponsibility is promoted by the fact that these countries believe that they have a backing from other economies is something that ought to be investigated, even as the support for the implementation of austerity measures in the countries severely affected continues.

The functioning of the Euro system depends on the efficient national budgets, which means that the economic construction of each country is a vital element for the survival of other countries. The political rhetoric should be eliminated from the debate, considering the fact that these countries can hardly abandon the Euro. In addition, the stakeholders have to devise a system of checks and balances for each country to avoid such a crisis in the future.

Appendices

Reference List

Baimbridge, M, Burkitt, B, & Whyman, P 2012, ‘The Eurozone as a flawed currency area’, Political Quarterly, vol. 83, no. 1, pp. 96-107.

Brittan, S 2010, ‘The euro? Will it still be around five years from now?’, International Economy, vol. 24, no. 2, pp, 6-10.

Dadush, U 2013, ‘Who says the euro crisis is over?’, Wall Street Journal Asia. Web.

Dinan, D 2012, ‘Governance and Institutions: impact of the escalating crisis’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, vol. 50 no. 2, pp. 85-98.

‘European union: Solidarity is under threat from crises’ 2011, OxResearch Daily Brief Service, p. 1. Web.

Farrell, H, & Quiggin, J 2011, ‘How to save the euro–and the EU’, Foreign Affairs, vol. 90, no.3, pp. 96-97.

Forelle, C, Walker, M, & Galloni, A 2010, ‘Europe vows to save Greece’, Wall Street Journal. Web.

Foroohar, R 2013, How Germany can save the Euro, Time Incorporated, New York, NY.

Francis, D 2012, How to protect your investments from the Euro crisis, U.S. News and World Report, Washington.

Hall, PA 2012, ‘The economics and politics of the Euro crisis’, German Politics, vol. 21 no. 4, pp. 355-371.

Heisbourg, F 2012, ‘In the shadow of the Euro crisis’, Survival (00396338), vol. 54 no. 4, pp. 25-32.

Higgins, M, & Klitgaard, T 2011, ‘Saving imbalances and the Euro area sovereign debt crisis’, Current Issues In Economics & Finance, vol. 17, no. 5, pp. 1-11.

Higgins, M, & Klitgaard, T 2014, ‘The balance of payments crisis in the Euro area periphery’, Current Issues In Economics & Finance, vol. 20 no. 2, pp. 1-8.

Kalafati, M 2012, ‘How Greek healthcare services are affected by the Euro crisis’, Emergency Nurse, vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 26-7.

Karras, G 2011, ‘From hero to zero? The role of the Euro in the current crisis: Theory and some empirical evidence’, International Advances in Economic Research, vol. 17 no. 3, pp. 300-314.

Melander, O 2011, ‘Dancing spreads: Market assessment of contagion from the crisis in the Euro periphery based on distress dependence analysis’, International Advances In Economic Research, vol. 17 no. 3, pp. 347-363.

Milios, J, & Sotiropoulos, D 2010, ‘Crisis of Greece or crisis of the euro? A view from the European ‘periphery”, Journal of Balkan & Near Eastern Studies, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 223-240.

Münchau, W 2013, ‘The Euro at a crossroads’, CATO Journal, vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 535-540.

Rosenthal, J 2012, ‘Germany and the Euro crisis’, World Affairs, vol. 175, no. 1, pp. 53-61.

Salin, P 2012, ‘There is no euro crisis’, Wall Street Journal. Web.

Walker, M, & Galloni, A 2013, ‘Embattled countries cling to euro’, Wall Street Journal. Web.

Walker, M, & Steinhauser, G 2013, ‘Control issues: Plans for political union unravel in Europe’, Wall Street Journal. Web.

Wood, S 2012, ‘The Euro crisis’, Policy, vol. 28 no. 1, pp. 32-37.

Xafa, M 2010, ‘Role of the IMF in the global financial crisis’, Cato Journal, vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 475-489.

Zuckerman, MB 2011, Mort Zuckerman: Why America should worry about the Euro crisis, U.S. News and World Report, Washington, D.C.