Introduction

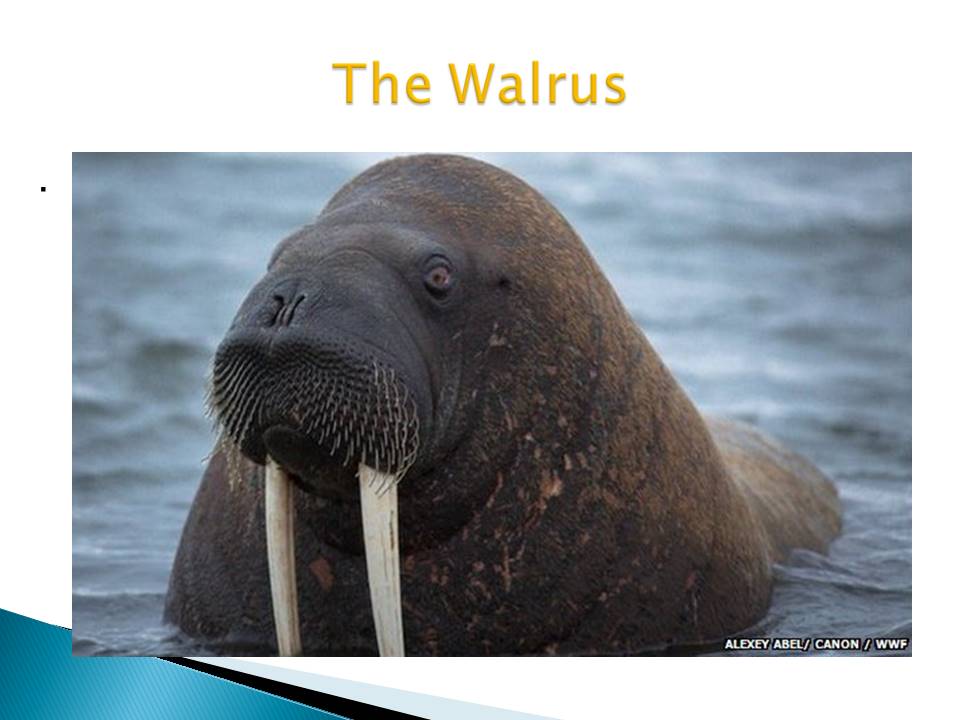

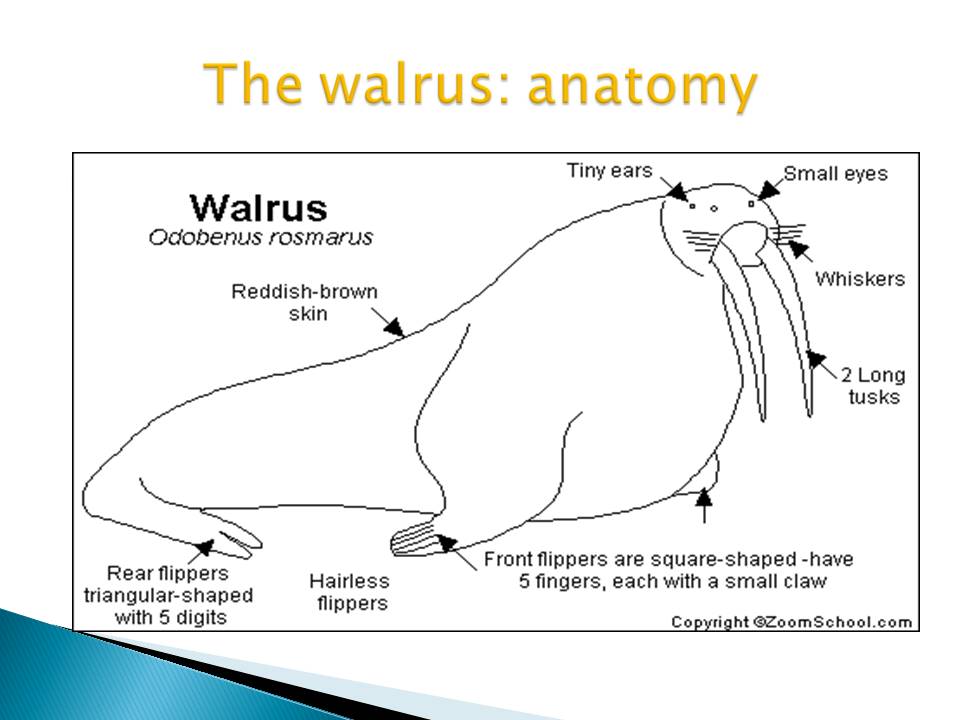

One of the largest mammals in the Arctic, the Walrus (Odobenusrosmarus) discontinuously distributed population in the:

- Arctic Ocean,

- North Pole and

- Northern Hesmispere (Bolster 2012).

Three sub-species are documents- divergens, rosmarus and laptevi based on their habitats.

The sub-species reside in the Pacific, Atlantic and Laptev Sea respectively (Bolster 2012).

In the pacific, most Walrus populations spend summers in:

- North of the Bering Straight,

- along the eastern coast of Siberia and

- Northern Alaska and other regions (Bolster 2012).

In winter, the animals move to the south to avoid excessive cold (Fisher & Stewart1997).

Foraging

The walrus forages on the sea floor and platforms of sea ice (Gjertz & Wiig 1992).

They must live in shallow seas, especially close to the shores:

- The deepest the animal can move is about 70-80 meters (Born, Rysgaard, Ehlmé, Sejr, Acquarone & Levermann 2003).

- In most cases, a walrus remains submerged below the surface,

- It can stay for up to two hours before coming on the surface to breath (Oliver, Kvitek & Slattery1985)

The sea floor is rich in a number of diet favorable to the animal.

The diet

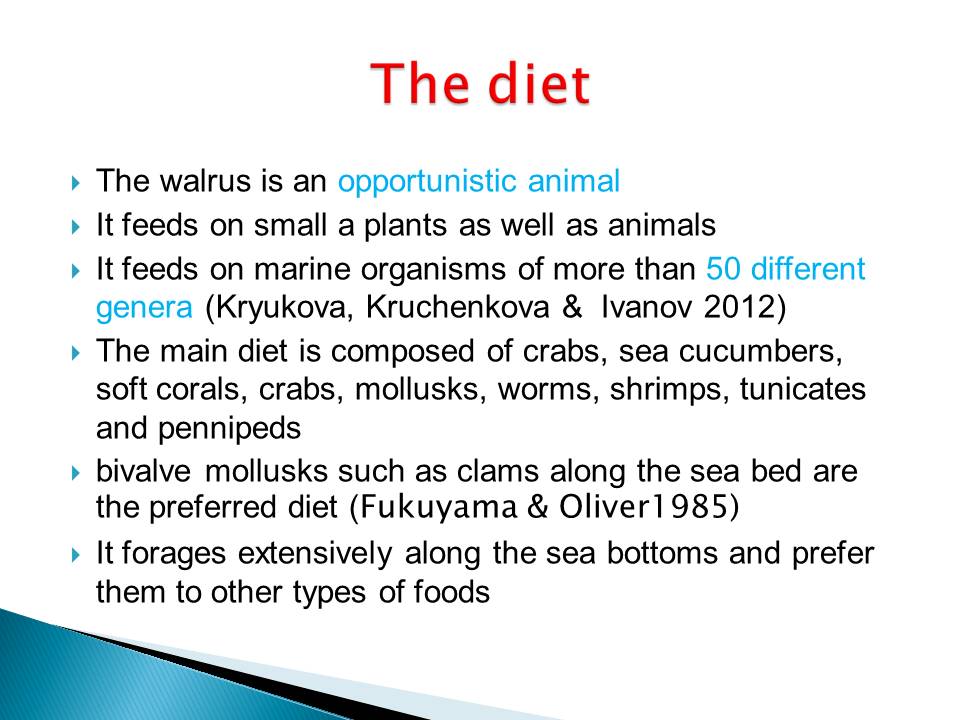

The walrus is an opportunistic animal.

It feeds on small a plants as well as animals.

It feeds on marine organisms of more than 50 different genera (Kryukova, Kruchenkova & Ivanov 2012).

The main diet is composed of crabs, sea cucumbers, soft corals, crabs, mollusks, worms, shrimps, tunicates and pinnipeds bivalve mollusks such as clams along the sea bed are the preferred diet (Fukuyama & Oliver1985).

It forages extensively along the sea bottoms and prefer them to other types of foods.

Detection and ingestion of food

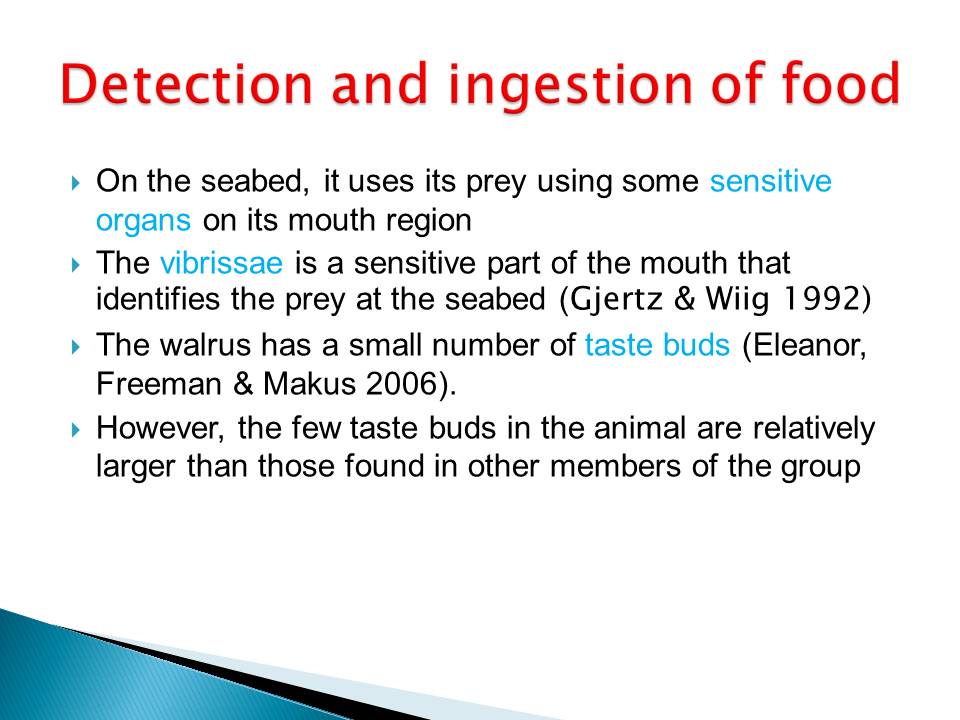

On the seabed, it uses its prey using some sensitive organs on its mouth region.

The vibrissae is a sensitive part of the mouth that identifies the prey at the seabed (Gjertz & Wiig 1992).

The walrus has a small number of taste buds (Eleanor, Freeman & Makus 2006).

However, the few taste buds in the animal are relatively larger than those found in other members of the group.

This aids the movement of other organism, making it possible for the walrus to fid its prey.

Walruses have powerful lips that play significant roles during feeding (Nelson, Johnson & Barber Jr 1987).

- To obtain the meat from the prey, the animal must such flesh by sealing the lips to the organism (Kryukova, Kruchenkova & Ivanov 2012).

- It withdraws the tongue rapidly into its mouth.

The tongue is another strong and important piece of the mouth and resembles a piston.

The mouth chamber creates a huge vacuum (Ovsyanikov 2002).

The animal has a vaulted palate that allows the suction of the prey into the vacuum.

The ingested flesh is swallowed directly after ingestion.

Studies have show that the animal does not chew its food (Born, Andersen, Gjertz & Wiig 2001).

However, the animal has cheek teeth that wear as it gets old (Dehn, Larissa-A, et al 2007).

Walruses also swallow small stones as well as pebbles.

But they have no effect on the animal.

Some tissues of the seal have been detected in the stomach (Witting & Born 2005).

Large male walruses may attacks and feed of larger seals such as those with more than 180 kg (Bogoras 2002).

Walruses feed on seabirds such as the Guillemont.

The animal consumes between 3% and 7% of its total body mass (Bockstoce & Botkin 2002).

They fill their stomachs to the full capacity twice per day when adequate food is available.

Conclusion

The walrus is an example of sea animals with well known foraging habits.

It is also an omnivorous sea mammal, feeding on both animals and plants.

A diverse and wide range of food variety makes it possible to survive in large populations.

Foraging habits are characterized with wide range movements along the seabed.

Foraging areas are shallow sea beds with a lot of vegetation to allow the existence of various organisms.

References

Bockstoce, JR & Botkin 2002, “The Harvest of Pacific Walruses by the Pelagic Whaling Industry, 1848 to 1914”, Arctic and Alpine Research vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 183–188.

Bogoras, W 2002, “The Folklore of Northeastern Asia, as Compared with That of Northwestern America”, American Anthropologist vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 577–683.

Bolster, WJ 2012, The Mortal Sea: Fishing the Atlantic in the Age of Sail, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Born, EW , Andersen, LW, Gjertz & Wiig, Ø 2001, “A review of the genetic relationships of Atlantic walrus (Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus) east and west of Greenland”, Polar Biology vol. 24, no. 10, pp. 713–718.

Born, EW, Rysgaard, S, Ehlmé, G, Sejr, MK, Acquarone, M & Levermann, N 2003, “Underwater observations of foraging free-living Atlantic walruses (Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus) and estimates of their food consumption. Polar Biology, vol. 26, no. 5, pp. 348-357.

Dehn, Larissa-A, et al 2007, “Feeding ecology of phocid seals and some walrus in the Alaskan and Canadian Arctic as determined by stomach contents and stable isotope analysis,” Polar Biology vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 167-181.

Eleanor, EW, Freeman, M & Makus, JC, 2006, “Use and preference for Traditional Foods among Belcher Island Inuit”, Arctic vol. 49, no. 3, pp. 256–264.