In 1799, the Napoleonic army was digging an addition to a fort in Rosetta, Egypt, when they stumbled upon a stone slab with strange engravings (British Museum, 2017). It turned out to be a temple stela from the Hellenistic era, inscribed with a priestly decree concerning King Ptolemy V in hieroglyphs, Demotic, and Ancient Greek (British Museum, 2017). Hieroglyphs had fallen out of fashion and become unreadable by the nineteenth century, but scholars maintained knowledge of Ancient Greek (British Museum, 2017).

Thus, the Rosetta Stone became the key to deciphering ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs. After Napoleon’s defeat, the Stone passed to Britain, and it has been on display at the British Museum for the last two hundred years (British Museum, 2017). It is currently a controversial cultural object because some historians are demanding its repatriation back to Egypt (Volante, 2018). A formal visual analysis of the Stone reveals its historical significance without even delving into its context.

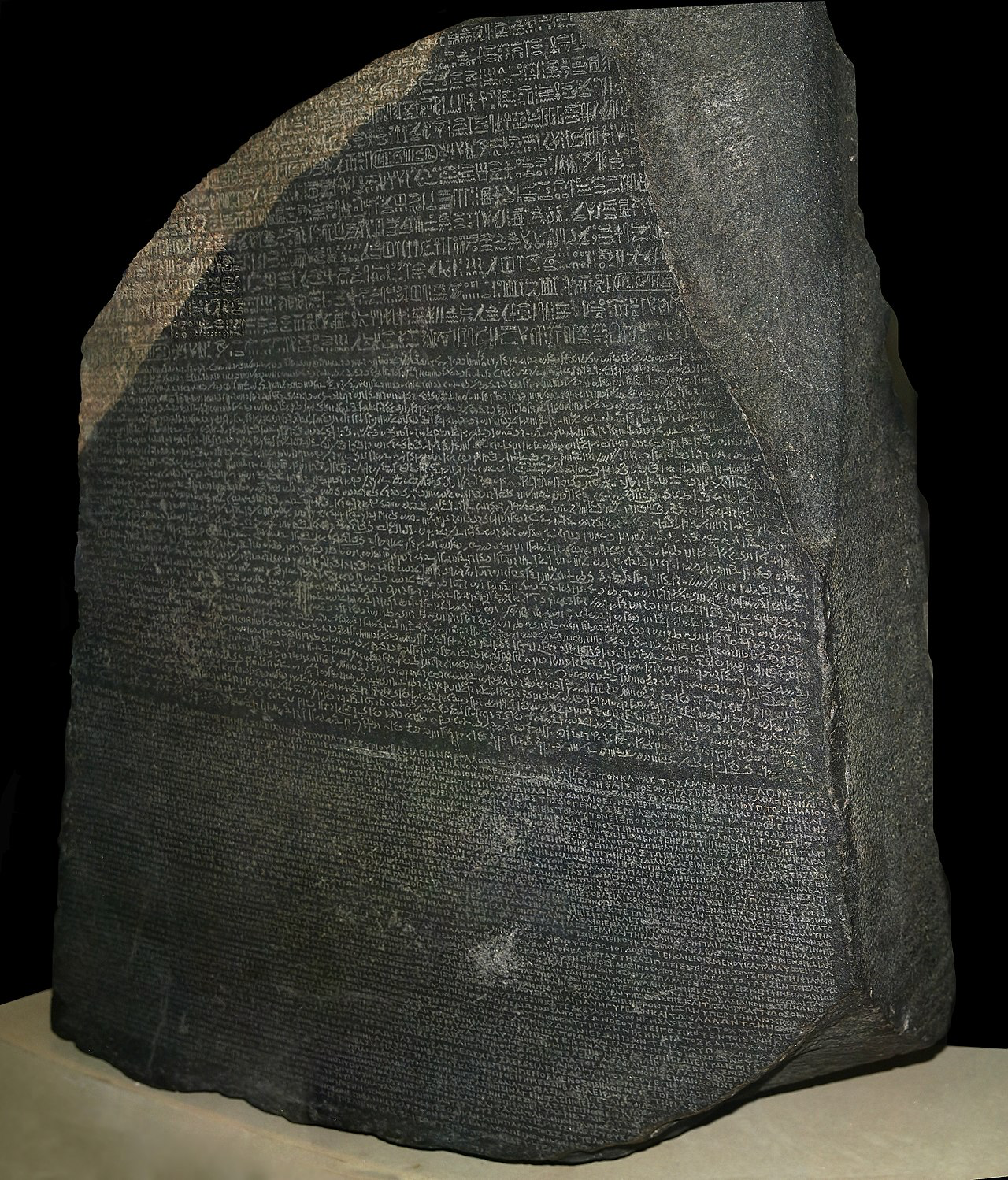

The Rosetta Stone is an irregularly-shaped fragment of a larger stele that clearly communicates its status as an ancient artifact. The top was broken off in antiquity, but the remaining part is undamaged and legible. It is made out of black granodiorite, which lends it a dark gray color that contrasts with the white text, yet the saturation has decreased over the centuries and has a washed-out effect with a few insignificant scratches. It was originally a geometric rectangular shape that was meant to be viewed from a singular vantage point. The front is a flat polished surface with lightly incised text, but the other three sides of the Stone are blank.

The sides are smoothed, and the back is uneven and rough. Approximately three-fourths of the slab’s outline retains its original shape before veering off into soft edges that have been rounded off by the passage of time. It is a well-preserved but nonetheless aged relic. The texture is smooth and weathered. It is freestanding and currently on display in a specially built glass case. The general appearance of the Stone and its display method express its age and historical distinction.

Since the Stone was originally meant to be read, the surface is completely covered in the straight text except for the line break between each script, signifying a visual division of space. It was lightly incised on a vertical axis in a negative technique. The Stone is self-contained, removed from the viewer, and progresses downward with the text. Since the top is broken, the first part containing the hieroglyphs is the smallest component, but the middle and bottom parts take up roughly the same amount of space. The font and space between lines of text become smaller in each successive part, and the text subsequently becomes denser.

The lines of the letters are very precise and clearly legible. There is no emphasis on any particular part of the remaining structure or interplay of light and shadow since it is a flat surface. The precision and abundance of the incised text signify that the stele’s original function was to communicate important information.

In conclusion, the formal elements and design principles of the Rosetta Stone convey its significance both at the time of its creation and at the current moment. The polish of the surface and the text’s careful incision prove that the stele had a function worthy of its time-consuming production. The Stone has deteriorated and acquired a smooth, weathered appearance over the course of time but remains well-preserved and readable. An ordinary priestly stele became our most significant historical artifact because it enabled us to understand ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs and culture.

Annotated Bibliography

British Museum (2018). Everything you ever wanted to know about the Rosetta Stone. Web.

This is an introductory post to the Rosetta Stone, published by the official online blog of the British Museum. It explains that Napoleon accidentally discovered the Stone in 1799 and that it became the property of the British on his defeat and has been on display in the British Museum for the last two hundred years. The post explains how it was deciphered by European scholars and became the key to understanding hieroglyphics. There is a brief visual description of the three scripts and a summary of the stela’s initial function in Ancient Egypt. Finally, the authors present links to a Youtube summary, a BBC podcast, and replicas of the Stone in the museum gift shop.

It was written for a general audience with no prior knowledge of the Rosetta Stone and thus presented a short, accessible summary of its significance and discovery. This is an appropriate source for the introductory purposes of this paper but by no means a comprehensive overview of the Stone’s history. It is important to note that the British Museum is a public institution and is thus motivated to gloss over the controversial parts of British history. This post does not explain why cultural artifacts were seized by imperialist powers or why it was transferred into the hands of the British Empire instead of Egypt upon Napoleon’s defeat. In fact, the word “empire” or the current controversy surrounding demands for the Stone’s repatriation back to Egypt is not mentioned at all. While the statements published on this site are credible facts, it is important to consider which details were overlooked for the sake of ideology and protecting the Museum’s interests.

Hans Hillewaert. (2007). Rosetta Stone [photograph]. London, UK: British Museum.

The Rosetta Stone is one of the most significant cultural artifacts on display in the British Museum. This photograph is one of several made of the object, but remains the best one for the purposes of the essay because it clearly shows its different visual elements.

Volante, A. (2018). Renouncing the universal museum’s imperial past: A Call to return the Rosetta Stone through collaborative museology [Master’s Thesis, University of San Francisco]. Scholarship Repository. Web.

Volante argues that the seizure of the Rosetta Stone from Egypt and its following display in the British Museum is the legacy of orientalist ideals, colonialism, and imperialism. The West claimed political, cultural, and social superiority over their colonies, and thus saw themselves as guardians of important cultural artifacts. European museums supported this ideology because it enabled them to profit off the systematic plunder of places such as Egypt. Indigenous populations were intentionally excluded from the study of their own culture, and it became the grounds for a power struggle between the French and British empires.

The British Museum has so far refused to return the Rosetta Stone because it believes that certain artifacts are part of the “common human culture” and thus transcend their place of origin. Volante disproves this position and asserts that museums need to advocate for knowledge and social justice, not focus solely on the ownership of objects. She outlines a plan for the repatriation of the Rosetta Stone through a collaborative project between the British Museum, Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities, and the source community of the Stone in Rashid, Egypt.

This is a thesis by a Master of Arts in Museum Studies from the University of San Francisco. Considering that the author is a graduate student and her advisor does not specialize specifically in Egyptology, this is an introduction to the subject appropriate for the level of this essay but not an authoritative source by an expert. Further research should be completed before definitively choosing a position on this issue. It was written for an audience with little prior knowledge of the Rosetta Stone and followed a coherent, easy-to-understand line of argumentation. It is a succinct summary of imperial museology, the issue of cultural appropriation, and the controversy currently surrounding the British Museum and the Rosetta Stone.