Introduction

The global environment has presented numerous challenges to the firms in their quest to satisfy customer needs and expectations. In order to remain competitive therefore, most firms have launched Total quality Management (TQM) programs, both for the employee and processes.

These programs are considered an attempt by company management to continually improve the quality of products and processes. Principally, TQM considers the producers as well as the consumers to be responsible for the quality of products and processes offered by the organization. Thus, the contribution of the suppliers, management, employees and customers is significant in meeting and even exceeding customer quality expectations.

As such the term Total Quality Management means different things to different people; designers expect the product or service to conform to specifications; producer expects the product to perform or fit into intended use; consumers expect the product to be useful according to the price paid; users of products expect equally good support services after using the product; and the judgmental evaluation of the product or service constituents (Juran, 1988).

The meaning of quality

Quality therefore means different things for both manufacturing and service organizations. While manufacturing organizations base their perception on the tangibility of their end-products, service organizations have to contend with their intangible products.

According to Ahire (1997, p. 91) manufacturing organizations often define quality on the basis of conformance, which determines how much of the preset standards that the product meets. Other dimensions of quality within the manufacturing organizations include reliability, whereby the product will be expected to perform fully; performance, increasing in functions; serviceability, the ease of being repaired; and durability, which refers to the additional features on the product.

The service organizations on the other hand perceive quality through customer-oriented dimensions. Due to the in-tangible nature of the products, the consumers cannot touch but instead experience the quality of the services. The definition of quality that is based on feelings and perceptions, mean that definition of quality is a demanding task.

Such perceptual factors infer to the responsiveness to the needs of the customers. Examples include friendliness and courtesy of the employees, prompt solution to complaints, minimal time spent by a customer waiting for a service to be delivered, and consistency of the service features over a period of time.

BR Engineering as a manufacturing organization intends to introduce formalized quality procedures and develop TQM environment in its quest to enter the aerospace and automotive industries. In the precision machining business and ‘general engineering’ applications that BP has specialized in, ‘traditional’ aspects of engineering might have fulfilled the quality targets of the organization.

However, the aerospace/automotive industry where 99-percent quality is considered not good enough, involves the risk of losing human lives if the systems do not comply with the required quality standard. Thus, the MDs fears concerning the cost effectiveness of the TQM strategy should be calmed because human life is more important to ever organization.

Similarly, cost has been associated with quality because most organizations have become aware and cautious of the high cost of poor quality. Such that if BP engineering prefers adopting the ‘traditional’ engineering in its venture into the aerospace/automotive industry, the long-run costs associated with poor quality will not match the cost that would have been injected in preventing the poor quality.

Hence quality primarily results in loss of business due to dissatisfied customers and increase in other costs. The costs associated with product quality are quality control costs and quality failure costs. While quality control costs are incurred while achieving high quality, quality failure costs result from poor quality. Further, the costs can fall into appraisal and prevention costs, and internal failure and external failure.

The prevention costs are costs incurred in an effort to prevent the occurrence of the two quality failure costs. Therefore, the cumulative value of the four poor quality costs, both before and after the manufacturing process, cannot be compared to the future immeasurable loss of business due and dissatisfied customers (Cua, McKone and Schroeder, 2001, p. 675-79).

Prior to the adoption of TQM by manufacturing and service organizations, the traditional standard of conformance to specification stipulated the target value for product quality, but allowed certain margins of error, such as 5.00 + 0.20. The losses in form of cost were reported when the product dimensions went beyond or fell lower than the control limit (Juran, 1988).

According to the theory by Dr. Taguchi, product that meets the target specifications is very different from one whose quality nears the control limit, for a designer. But for a customer, there is little difference between the two products. Thus his view that organizations should focus their efforts on quality at the design stage was considerably cheaper than during the production process.

Dr. Taguchi’s engineering approach to product design known as design of experiment aimed at developing a robust design. The design would generate products that could perform in a range of environments. This designer was motivated by the premise that it was easier to control the features of a product to fit into verity of environments than trying to change the prevailing environmental conditions.

Quality dimensions

The specific dimensions of quality for manufacturing products include, performance, the basic operating features of a product; features, the “additional” items added to the product’s basic features of a product; serviceability, the ease, speed and possibility of getting repairs; durability, the product’s life span before repair; conformance, probability of the product meeting pre-designed standards; safety, assurance of not being harmed while using the product; esthetics, the sound, look, taste or feeling of a product; and reliability, that the product is guaranteed to work properly over an anticipated period of time.

Therefore, customer satisfaction begins when a customer has been allowed to pay according to the financial capability, as long as they are getting the value for their money (Cua, McKone and Schroeder, 2001, p. 681).

Customer satisfaction – Needs and Expectations

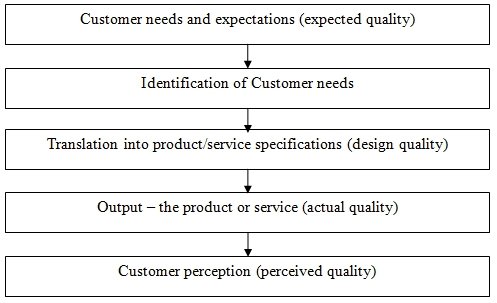

The customer driven quality cycle requires that both the planning of the products and system should be geared at meeting the expectations and needs of the customer.

Initially, the customer’s expected needs and expectations are stipulated before the producer identifies these specifics. After identifying the needs and expectations, the producer ensures that the final product meets the customer’s expectations by providing the output that contains the design features.

Philosophy of TQM

TQM is characterized by its focus on dealing with quality problems by indentifying their root causes and ensuring correction at the source, instead of identifying quality problems on the final product. The focus of TQM while ensuring the participation of everyone in the organizations ensures that the cumulative attention is directed to the customer.

Every member of the organization including the employees, customers, and suppliers are involved in the quality improvement process. The success of TQM depends on the adoption of the specifics aspects of the strategy (Goetsch and Stanley, 1995, p. 57).

Customer focus

Fundamentally, TQM features as the company’s collaborative effort to attend to the customer’s quality needs. In order to meet and often times surpass the customer’s quality standards TQM acknowledges that a product that is not according to the customer’s specifications becomes of no value to the company. Although TQM is targeting the customer, knowing the exact quality that a customer needs is affected by their changing tastes and preferences with time.

Further, variation of customer demands from one customer to the other complicates the determination of exact customer expectations. In order for companies to match up with the continuous preference changes, say in the auto or the retail industry, constant market surveys, focus groups and interview of customers should be conducted to collect adequate information about the changing customer expectations.

According to Cua, McKone and Schroeder (2001, p. 684) the philosophy associates the success of the company with the satisfaction of the customer. In the case of BP Engineering, attention to the customer requirements means more than eradicating defects or errors, but also meeting customer specifications by mitigating customer complaints.

Total quality participation by the company as a whole means that at one time they operate as suppliers to other participants, and they operate as customers at other times. In the case of BP Engineering, supplies to the lower by the upper departments, such as the technical to the production will mean treating them with relatively equal attention as an external customer would be handled.

Continuous improvement

Secondly, TQM focuses on continuous improvement; which is the philosophy of never-ending improvement. Previously, firms felt successful, and did not see the need to continue the improvement process once it had achieved a required level of quality. Figuratively, Rosenberg believes improvements are like plateaus that are achieved one after the other while reducing the number of defects to need a set level of requirements, especially if a given level of quality has been identified to highly satisfy a customer’s needs (1996, p. 59).

Managers in global companies each perceive such change in various ways; such the traditional view of American managers termed it as organizational restructuring; that the most lasting and perfect changes emanate from gradual improvement, which involve bit by bit uptake of doses than one large dose.

According to the Japanese, continuous improvement, or Kaizen, expects the company to continually target to become better through problem solving and learning.

Because perfection is a long-away target for most companies aiming to improve on quality, performance should on a timely basis be evaluated and measures taken to adopt improvements. In addition to product quality, that is associated with process quality, continuous improvement is also targeted toward the company process improvements (Zimmerman, Steinmann and Schueler, 1996, p. 22).

However, for manufacturing organizations such as BR Engineering the major components of continuous improvement include waste management; prevention of defects instead of detection; and emphasis of quality during the design of the product rather than after production.

Hall (1987) suggests that this customer-focused approach ensures that errors are mitigated to provide the customer with defect-free products. Problems likely to face the process of product development are discovered and taken care of before getting to the preceding internal customer. Companies can foster their continuous improvement (CI) through a number of approaches.

As the first approach to CI, the The plan–do–study–act (PDSA) cycle is a series of activities that necessary for an organization’s incorporation of CI. As a cycle, the continuous nature of PDSA cycle means that it is an ever-continuous process. The PDSA cycle is made up of the following steps:

Step one known as Plan, expects the analysis of commissioned and existing plans by the managers towards a solution. The improvement plan and appropriate measures of performance evaluation should be based on the information (Ahire 1997, p. 96).

The second step, Do, of the PDSA cycle refers to the implementation (doing) of the plan. In this stage, the managers will be expected to collect relevant data and document resulting changes to ease the evaluation process.

In the third stage of the PDSA cycle, study, involves evaluation of the data collected in the second stage. This is a check as to whether the initial plan is achieving the planned goals.

Lastly, the fourth stage of the PDSA cycle, Act, depends on the evaluation results of the preceding three stages. The implementation of the new procedure to test its success begins with the communication of the results to all the members of the company. Just as the name suggested, the cycle starts immediately after the action stage, and the evaluation of the process continues indefinitely (Cua, McKone and Schroeder, 2001, p. 688).

The Second approach towards the implementation of the CI is benchmarking, which involves analyzing business practices and operations of companies that are ranked “best in class,” with the intention of making comparisons.

For instance, BR Engineering would seek to analyze and learn from the operations of other automotive companies, though it does not necessarily need to be a similar industry company. The primary aspect being that the benchmark company is excelling in aspects of operations occurring in the company doing the benchmarking. Internationally, American Express has been widely used as a benchmark in conflict resolution issues (Ahire 1997, p. 95).

Continuous improvement (a process approach)

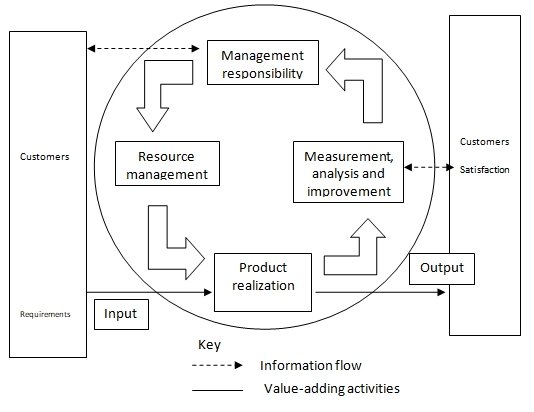

According to Medori and Steeple (2000, p. 521), the process approach involves the application of a set of processes in addition to the identification, integrations and management of the same, to result in the desire outcome.

In conjunction with the quality management system, the process approach of continuous improvement ensures that the producer not only comprehends the quality requirements, but also purposes to meet them. Further, the approach ensures addition of value through the processes; ensures effective performance, and uses the measured objectives as a basis of the un-ending improvement process.

Continuous improvement of the quality management system

According to Deming’s philosophy, the continuous improvement would ensure the ultimate philosophy is achieved through a number of signposts, including;

- Establishing a mainstream purpose to ensure long term organizational goals through product improvement

- Instead of accommodating certain levels of poor quality products, the manufacturer should adopt and stick with a policy of preventing poor quality

- Rely on statistical quality to improve product design and process, in turn eliminate the need for inspection to achieve desired quality

- Resorting to working a few suppliers or vendors that have or will comply with TQM, rather than make decisions based on competitive prices

- Regularly ensure improvement the production process through the system and employees, being the major sources of quality problems, hence reducing costs and increasing productivity

- Introduce training of workers that aims at reducing quality problems through the adoption of statistical quality control techniques

- Help workers improve their performance by instilling leadership among their supervisors

- Encourage and motivate employee participation by cutting on the likelihood of reprisal for identifying quality problems or asking questions

- Foster cooperation and the culture of working together by eliminating barriers across departments

- Encouraging workers to achieve numerical targets and high performance by first orientating them on how to achieve the set targets

- In order for workers to perform to their capabilities, improvement in the production and supervision process to enhance worker self esteem and pride

- Throughout the organization from top management downwards, provide involving training and education on methods of quality improvement, to enhance continuous improvement

- Ensure that the top management has made a commitment to implement the above thirteen points

Employee empowerment

The third aspect of Total Quality Management philosophy, employee empowerment, exists in the premise that employees can be able to identify and solve problems if they are tasked with certain responsibilities. Traditional forms of quality approaches caused employees to shy away from pinpointing problems due to the consequences.

Instead, the problem of poor quality ended up being “someone else’s problem” because it was ignored and thus transferred to another department in the company. Under TQM problem identification is among the priorities of all the employees, and incentives are awarded for efficient problem identification and possible management.

Hence the company employees play significant role in quality production and process, with most TQM-compliant companies empowering their employees to make vital decisions during these processes. Their performance in the vital production processes backed by the constant and detailed training programs, because a well trained workforce provides a successful TQM environment (Medori and Steeple 2000, p. 523).

Furthermore, as the name suggests, buyers of company products are external customers. But internal customers are the workers who receive goods from the various departments along the production process. For instance the marketing department serves as an internal customer to the packaging department; and as much as a poorly packaged product should not be passed to the external customer, a defective product should not be passed to an internal customer (Cua, McKone and Schroeder 2001, p. 694).

A Quality circle is one of the common types of team involving a group of volunteer production employees coordinating with their supervisors to attend to quality problems. some features of the team include, eight to ten members; decision-making based on majority; meetings held weekly during work hours; and adhering to an agreed procedure while analysis and solving quality problems. During the meetings, criticisms are prohibited but open discussion is allowed, especially due to the casual and friendly but serious atmosphere.

Firms that have succeeded in the implementation of TQM acknowledge that the successful adoption of quality circles. However, the success of quality circles depends on the employees abilities to identify and correct problems. In order for workers to efficiently analyze, interpret and correct quality problems, adequate training in the various quality control tools is compulsory (Ahire 1997, p. 99).

The seven tools of quality control include cause-and-effect diagrams, flowcharts, checklist, control charts, scatter diagrams, Pareto analysis, and histograms.

Product design

By ensuring that the product design meets, and some time surpasses customer expectation, is a crucial aspect of building quality into a product; possible through the concept of Quality function deployment (QFD). Practically the implementation of the procedures is an involving task, simply because the customer meaning of quality varies from one to the other.

Medori and Steeple conclude that it is vital that the customer’s everyday language for quality into comprehensible technical specifications, in order to produce a product that customers want. It is through the use of QFD that communication is enhanced between different company functions, such as engineering, operations and marketing (2000, p. 530).

Through QFD, variables involved in the product design exhibit relationships such as technical versus customer expectations. For instance, an automobile manufacturer’s analysis of how changes in materials would affect customer safety expectations will be vital in developing a product design that suits customer needs, while saving the technical department from unnecessary requirements.

Process management

In order for quality to be reported in the final product, TQM stipulates that quality should prevail during the production process; through building quality into the process, instead of discarding defective items after the production process is complete, it is better and cost-effective at that, to uncover the quality problem source and correct it; this is possible through the concept of quality at the source.

No dealing with the source of the problem will cause the problem to persist and even lead to greater losses. Unlike the traditional approach to quality solutions, which proposed quality checks after a particular stage, quality at the source’s new approach prevents the quality problem from being transferred to the final consumer. Monitoring and management of process quality can be conducted using such quality tools as control charts (Medori and Steeple 2000, p. 533).

Managing supplier quality

Traditionally the numerous suppliers to a company would be allowed to deliver their raw materials through a series of competitive price bidding. That the materials were later checked for quality after delivery, is according to TQM, a contributing factor to poor quality cost plus time wastage.

As such, TQM extends the requirements of quality vertically to the suppliers. Quality supply will therefore not be checked upon delivery, thus saving on time and costs. This they accomplish by having a company representative at the supplier’s location to elaborate the quality process, thus incorporating the supplier from the design stage to the final production (Zimmerman, Steinmann and Schueler 1996, p. 28).

Benefits of TQM

Implementation of TQM will benefit BR engineering in various ways. Through the improved communication channels within and across functional areas, management and supervisors get wind and embark on solving employees’ problems. Employees benefits from job satisfaction increasing their loyalty to the company.

Further, the employee empowerment principle of TQM makes employees feel participatory and motivated in the company operations, thereby reducing turnover rates, costs and tardiness but instead increase efficiency and productivity. Establishment of teams and training programs provides opportunities for employee personal growth and development.

Improved coordination across company functions develops mutual respect between management, employees and customers. Successful implementation of TQM, improves company awareness and company solidarity; reduces the frequency of defect right from the supplier down to the consumer; thereby providing both internal and external customers with products that meet quality expectations (Rosenberg 1996, p.60).

However, the success of TQM and the recurring benefits above requires that BR engineering top and middle level management put their full support behind the initiative. The functional areas of the organizational should encourage communication with every department. Additionally, every stakeholder should commit to the suggested principle for the long-term, while the management measures guide programs and measure success on the basis of long-term profits.

Reference List

Ahire, SL 1997, “Management Science- Total Quality Management interfaces: An integrative framework”, Interfaces, vol. 27, no. 6, pp. 91-105.

Cua, KO, McKone, KE & Schroeder, RG 2001, “Relationships between implementation of TQM, JIT, and TPM and manufacturing performance”, Journal of Operations Management, vol. 19. No. 6, pp. 675-694.

Goetsch, DL & Stanley, D 1995, Implementing Total Quality, Upper Saddle River, Prentice-Hall.

Hall, R 1987, Attaining Manufacturing Excellence, Burr Ridge, Dow-Jones Irwin.

Juran, JM 1988, Quality Control Handbook, 4th edn, New York, McGraw-Hill.

Medori, D & Steeple, D 2000, “A Framework for Auditing and Enhancing Performance Measurement Systems,” International Journal of Operations and Production Management, vol. 20, no. 5, pp. 520–533.

Rosenberg, J 1996 “Five Myths about Customer Satisfaction,” Quality Progress, vol. 29, no. 12, pp. 57–60.

Zimmerman, RE, Steinmann, L & Schueler, V 1996, “Designing Customer Surveys that Work,” Quality Progress, pp. 22–28.