The issues of transactions occurring in the marketplace and consumers’ collective lawsuits have proven to be sensitive ones. Statistics show that cases increase from year to year, and Warburton (2020) demonstrates it in his book Economic Analysis and Law: The Economics of the Courtroom. However, in order to turn to the issues themselves, it is reasonable to revisit basic marketplace policies.

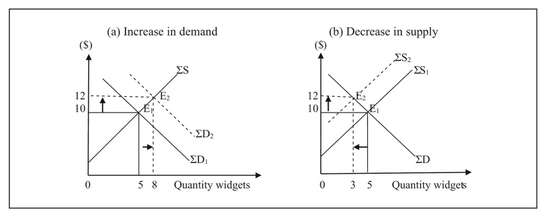

When demand increases – that is, change in demand occurs, not change in quantity required – prices and quantities increase synchronously. Contrariwise, if the market supply is reduced, the number of widgets supplied drops by a certain number of units, and the price per unit rises. The intersection of supply and demand curves demonstrates the sort of an agreement (equilibrium) that occurs in the market between agreeable buyers and widgets vendors. There are a number of reasons why equilibrium is thus important.

Essentially, equilibrium indicates efficiency in economics as well as in law. Efficiency there means the production of society’s desires as cheaply as possible. When it comes to an economy, efficiency has components such as production and distribution. In its turn, market efficiency is the lack of enforcement in cases of economic transactions. Buyers and sellers freely and willingly making transactional decisions must be founded on information available without deception. Such prerequisites reduce the likelihood of undesirable tensions (disequilibria) in the market, exceptions being the cases of economic shocks.

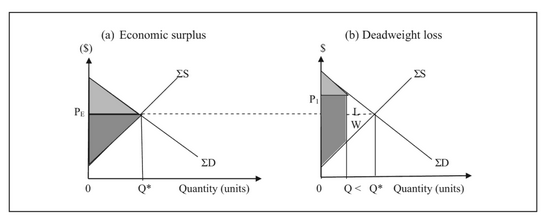

Consequently, equilibrium is an expression of fairness and stability in the market. Equilibrium demands adequate prices and all necessary resources be disposed to the services and goods production. It is to be noted, though, that market efficiency and equilibrium and efficiency have to be utilized with caution. Market equilibrium implies productive efficiency but does not exactly demonstrate it. An economic surplus is determined by fair market prices and efficient resource allocation. Price distortions, whatever the mechanisms, are distorting and lead to inefficacies that turn out to be costly to society. In other words, price distortions lead to inefficiencies. In order to take a closer look at it, Figure 1 is to be considered.

Panel (a) demonstrates how the economic surplus (ES) – a combination of producer and consumer surplus – is larger due to the market being in equilibrium. Additionally, P is a fairly acceptable market both by the sellers and the consumers. Economic resources are distributed efficiently, and no discernible efficiency decline occurs. Panel (b) showcases the results of disequilibrium – that is, price distortions. Consumers lose the L triangle, and surplus is transferred over to producers, but the whole society loses the W land.

Price distortion may be caused by a number of non-economic factors. These may be, along with others, illegal market distortions, which must be addressed by the courts of law in order to determine the level of loss associated with illicit price increases (P). The most visible causes of price distortions include irrelevant warning information, product liability, and market misrepresentation.

The identified causes combined create information asymmetries in the market, which in turn lead to negative selection that corrupts interactions in the marketplace between sellers and buyers. Corruption creates disadvantages that lead to market failures and inefficiencies equivalent to triangles L and W in Panel (b), Figure 1. Areas of L and W together are considered to be a deadweight loss. While individuals may seek redress for violations of trade regulations, consumers can as well exercise class action suits collectively for serious violations of trade laws.

In case of illegal price distortion, the market equilibrium can be achieved at levels that are lower or higher, as shown in Panel (a) of Figure 2. The demand curve shift forces equilibrium (E) at a price that is higher ($12) for the bigger unit quantity (8). This may be a consequence of false advertising or market fraud. In fact, consumers do not make decisions on the foundation of adequate information. Thus, equilibrium is not the desired result of marketplace information; it is artificial and must not be deemed indicative of market efficiency.

Over the course of time, consumers as a unity have opposed sellers who behave unacceptably. According to Warburton (2020), “a class action is a procedure by which a large group of entities—that is, a ‘class’—may challenge a defendant’s allegedly unlawful conduct

in a single lawsuit, rather than through numerous, separate suits initiated by individual plaintiffs” (p. 21). Generally, the courts have emphasized the effectiveness of considering socially desirable claims; for one, the Supreme Court has noted that the main purpose of collective claims is to increase the proceedings’ economy and efficiency.

Simultaneously, in some cases, class actions may result in defendants being subjected to costly or improper litigation due to the fact that the resolution of disputes may be cheaper than being tried in a court of law. Moreover, class lawyers might not pursue the interests of class members. Still, the class action is able to protect the accused from multiple, possibly inconsequent judgments. Class actions allow a large number of people to join their claims, and the accused might face exorbitant costs if deciding on no case settlement.

The complexities of such complaints as a category have given rise to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure designed to regulate the risks or abuses involved. The Federal Rule of Civil Procedure sets out the preconditions to be met by collective federal action and provides for verification and mandatory certification by the courts. A court is only to certify a class action if all mandatory requirements are met.

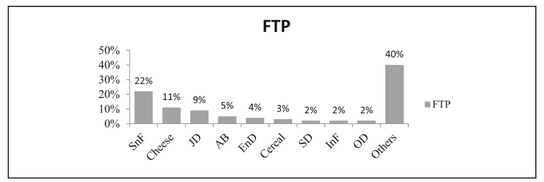

Particular products have been featured extensively in group claims. Warburton (2020) cites examples – one of them is the increased number of group food marketing lawsuits from 20 in 2008 to over 425 in 2015 and 2016 (p.21). A study conducted in 2015 shows that some 120 new food-related class lawsuits were filed or passed over to federal court (Warburton, 2020, p.21). In 2016, the number of applications increased, with more than 170 new food-related class lawsuits (Warburton, 2020, p. 21). Figure 3 demonstrates the categories of foodstuffs subject to the class action.

A recent study shows that particular products have some specific attributes in common, for example, trans-fat, product liability, and misrepresentation. Warburton (2020) cites that some lawyers working on class action focus on products containing so-called trans fats. It has been found that federal law precludes lawsuits conflicting with Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulations which demand products with a nominal PHOs (heavy phenolic oils) quantity to be labeled as 0% trans-fat (Warburton, 2020, p.22). However, the current FDA policy of eliminating trans fats has resulted in another portion of lawsuits, despite the fact that the agency has given manufacturers some time to alter their products.

Food group litigations reportedly involve a range of foodstuffs that can be found in the supermarket. Claims generally fall, according to Warburton (2020), into the following subdivisions:

- Natural,

- Slack fill,

- Origin,

- Specific health claim,

- Healthy foods,

- Looks healthy,

- Evaporated cane juice when white sugar is involved,

- Trans-fat,

- Processing, and

- Other representations” (p.22).

A product can be associated with one or more of these.

The information asymmetries issue in the marketplace has been repeatedly confirmed. For example, Warburton (2020) cites the study that claims that in the four-year span (2010-2014), 479 consumer group lawsuits, in which either a preliminary or a final settlement was approved by a judge, have been dealt with. The study had a focus on cases in which buyers, after having purchased an item or a service from the respondent(s), complained about a minimum of one of the following accusation categories:

- Misinformation,

- Products liability,

- Fraud,

- Misrepresentation and

- Antitrust.

There was a period of time when collective consumer claims in all the above-mentioned categories increased. Walburton (2020) states that it was between 2010 and 2013, and in this case, the defendants were representatives of a variety of industries, including banking, cosmetic industry/pharmacy, and retail (p.22). The financial sector – banking – is infamous for having both the majority of settled cases and about half of the total settlement dollars split by US$7.25 billion Visa/Mastercard settlements referred to above.

Furthermore, the motor vehicle industry accounted for a significant portion of the estimated costs. Warburton (2020) points to that figure is over 10 percent of the total settlement funds (p.23). If these two settlements were to be excluded, these would be more evenly allotted among industries, even though five relatively major fields – finances, industrial materials and products, consumer services, cosmetics industry/pharmacy, and electronics – have more than 10 percent of the total calculation each (Warburton, 2020, p.23).

Two fields – the entertainment industry/social media and telecommunication industry – account for a comparatively minor share, with each accounting for less than 1 percent of all settlements (Warburton, 2020, p.23). Appendices D and E represent the fund value for settlement years 2010-2013, as well as the reported and unaccounted value of the most common charges.

It is peculiar to note that fraud is the most common charge. Another study conducted in 2014 that Warburton (2020) cites shows that, among 321 selected cases, fraud turned out to be the most common charge, after which antitrust cases followed. The majority of the resolved cases contained allegations of fraud or misrepresentation – however, most of the settlement money – 56 percent of the total sum – were antitrust cases related (Warburton, 2020, p.23).

Speaking about cases of misrepresentation – alternatively, false advertising – pharmaceuticals and foodstuffs show high complementarity – and a high percentage of cases associated with these. Other complementary products, such as motor vehicle industry products, materials for building, and electronics, were characterized by a high degree of product liability. The sector of finance, bank accounts and loans, alongside insurances and mortgages, has shown to support fraud. Fraudulent activities comprise the largest proportion of cases for which settlement payments have been reported, while the biggest percentage of cases for which information on amounts paid in arrears has not been provided related to product liability.

In conclusion, transgressions and class action lawsuits are indicative of problems inherent in the hypothesis of the efficient market. As Warburton (2020) notes, consequently, issues of compensation to society for harmful experiences in the marketplace are raised. In addition to not knowing how compensations for social losses have to be distributed, the problem with social loss estimation (DWL) is the lack of knowledge of the demand curve’s exact slope. Demand elasticity, or the ability of consumers to respond to price changes, might be extremely useful.

Reference

Warburton, C. E. (2020). Economic analysis and law: The economics of the courtroom. Taylor & Francis.