Introduction

Culture can provide the foundation or the background for many different kinds of understanding. One common understanding, however, seems to be that it is related to human values one way or the other and, like culture, interest in human values dates back many years. The result is that culture belongs to a whole group, not to its individuals, and we cannot avoid it. It determines behavior, at the same time as it gives an anchoring point, an identity, a social place and a world view. The countries selected for expansion are Turkey and Thailand.

Culture Defined

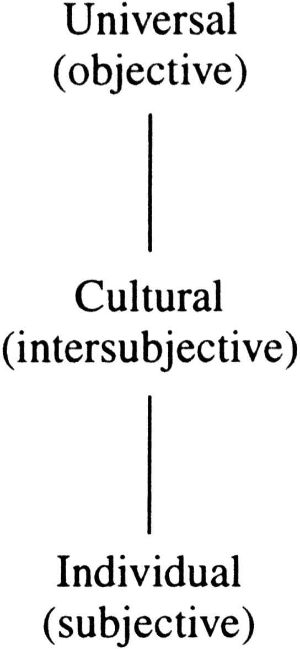

The accountant executives should take into account that across cultures, the same type of interface problems may occur. People carry around ‘mental programs’ (Hofstede, 1984, p. 14; see Figure 1). Every person’s mental programming is partly unique and partly shared with others. The most basic (but also least unique) level of programming is the universal one. This is shared by all, or almost all, human beings (Hofstede, 1984, p. 16). No two people are programmed exactly alike, even if they are identical twins raised together. This is the level of individual personality.

Management Culture

Turkey

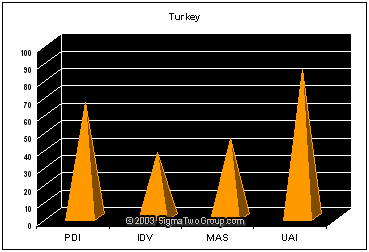

Turkey is a country located in the western Asia in the Balkan region. In this country, religion has a crucial impact on business relations and negotiations. Turkish employees have little experience of working in formal organizations which, combined with belonging to a high-contextual culture, means that much of what goes on as planning, supervising and controlling is more symbolic than substantive, as will be seen (see Figure 4). Many Arab institutions and business organizations are not very efficient, which is one reason why Arab executives prefer to use personal (family and friendship) ties instead of formal channels and apply a very personalized and informal management style.

Turkish management style supports more detail in planning (Hofstede, 1984, p. 264), and that Arabic managers systematically tend to take more variables into account when making strategic decisions or in purchasing decisions than American managers, but this is for symbolic not substantive reasons (Bartlett & Ghoshal 1999). Western-type quantitative management systems and data-based decisions will not work as such in this culture. In the Turkey, the cultural norms make it less likely that strategic planning activities are practiced in the first place, because they may put question marks to the certainties of today. If they are performed, ‘particularistic’ and ‘pragmatic’ thinking modes are emphasized (information is interpreted in the context of practical use and specific action) (Barham & Conway 1998).

Employees become morally involved in the company where they are employed. Subordinates and superiors also become more dependent on each other. Organizations have great influence on their members in Middle Eastern countries. The former are expected to assume a broad responsibility for the latter, providing expertise, order, duty and security (Brake et al 1995). Private life is invaded by organizations. Employees expect organizations to defend their interests. This is one reason why large companies are attractive and why labor unions are very rare in the Arab world. Friendship and trust are prerequisites for any social or business relationship and are developed slowly. These values play a larger role in the Arab type of culture. In fact, policies and practices are based on loyalty and a sense of duty in such a culture (Hofstede, 1984, p. 173).

“The manager is a dominant individual who extends his personal control over all phases of the business. There is no charted plan of organization, no formalized procedure for the selection and development of managerial personnel, no publicized system of wage and salary classification…. Authority is associated exclusively with an individual” (Harbison and Myers, 1959, pp. 40-41 cited Brislin 1993, p. 34).

One interesting aspect of the Turkish business culture is that the distinction between formal and informal is not very useful. It may appear, at first, that superior-subordinate interaction is very formal and restricted and that informal discussions with subordinates are avoided. This organizational type has been characterized as ‘full bureaucracy’, that is, relations between people as well as work processes are rigidly prescribed (Hofstede, 1984, pp. 215-217).

Thailand

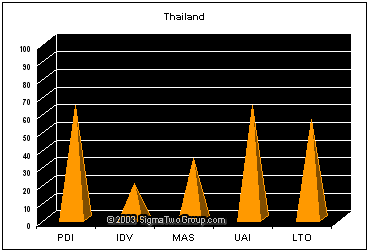

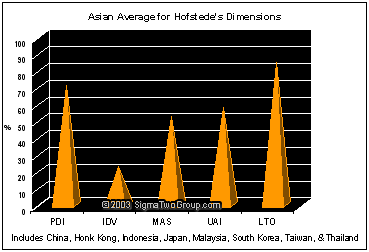

Thailand is a South Asian country bordered Cambodia, Laos and Malaysia. Characteristics of a Thai business enterprise include an autocratic, centralized style of management. Authoritarianism is a primary value in Eastern cultures in general. The Thai management style is both a function of the family character of management and a response to the hostility so often experienced in the external environment. The Thai type of culture implies (Hofstede, 1984, p. 92; see Figures 2,3): managers are seen as making decisions autocratically and paternalisitically; employees fear to disagree with their boss; weaker perceived work ethic; more frequent belief that people dislike work (Taggart & McDermott 1993).

Hierarchy is a primary value in Eastern cultures. In the Thai type of culture, this means greater centralization and tall organization pyramids (Hofstede, 1984, p. 107; Trompenaars, 1995, p. 144).Some say that the typified Thai organization structure is informal. ‘Informal’ is probably not the right word here, at least not in the sense of ‘unconventional’ and ‘unconstrained’, nor is the Thai organization formal in the sense of ‘planned’ and ‘impersonal’. The proper word for a Thai business organization is rather personalized. There are conventions as well as constraints, which are not planned or impersonal, and these are given by the person in the centre of the organization (the owner or his or her representative). These conventions and constraints may change at very short notice.

Another related conceptual problem is that Thai organizations are not personnel bureaucracies (where people, but not their procedures, are controlled), nor are they work flow bureaucracies. Personnel as well as work-flow are controlled in a typified Thai organization, but not as fully, consistently and impersonally (Sterman, 2000). In line with the above, personalized bureaucracy would be a better term to characterize Thai organizations and management style. Unlike Western firms that are supposed to concentrate on ‘core competencies’, in Thai firms managers want to have a hand in most things connected with their business. One characteristic of the Thai business leaders is that their power rests on high flexibility, adaptability and political pragmatism. In general, the Thai have a pragmatic view on how to get things done (scruples or no scruples) by considering each situation on its own merits, not following general guidelines (Punnett, 1994). Directness combined with a lack of the Western world type of abstract thinking are shown, among other places, at the negotiation table as a focus on the immediate transaction and as an immunity to logic (Steiner & Miner 1986; Putti, 1991).

Business Presentations: Products and Services

Turkey

Turkish culture and religious traditions have a great impact on customers’ values and image of the products, brand awareness and purchasing decisions. Turkish companies measure success by numbers and marketing limited to sales. Such Western inventions as advertising and sales promotion hardly exist at all (except in the networking sense). Concentrating so much on sales and sales numbers may occasionally mean that quality becomes of less significance. Lack of quality control is also often a problem in the workplace. Turkish enterprises may often appear impressive in terms of market capitalization and growth. Turkish employees value company’s image and relations with partners paying a special attention to customer satisfaction and customer loyalty (Schneider & Barsoux 2002; Keegan & Green 2000).

Thailand

The Thai employees seem to deliberately avoid entering the world of mass marketing and brand name goods. They have also no sense of after-sales service. Once a deal is done, it is done, and the nearest to anything we can call point-of-sales service would be the common Thai practice of ‘mooching’. Endless bargaining and a seemingly never-ending list, added to as the bargaining goes on, of ‘that little something extra’ has given the impression to outsiders that the Thai are among the toughest negotiators in the world. The Thai may appear obsessed and unreasonable, even ruthless, in negotiations. There is a Thai expression for this behavior when it is at its extreme, that is, to have ‘a thick face and a black heart’, to pursue one’s own ends without considering the effect of one’s actions on others, and not showing any emotion in the meantime (Hoecklin, 1995). By being politically pragmatic (often corrupt in Western eyes) and sometimes by copying (occasionally illegal in the same eyes), many Thai business millionaires have started from a humble trading position or an intermediary background (not very innovative professions), building up conglomerates concentrating on businesses such as property, shipping, hotels and telecoms. Because they find it hard to separate management from ownership, they tend to ‘avoid industries that require the complex integration of many different skills (Keegan & Green 2000).

Business Meetings and Negotiations

Turkey

Business meetings are culturally based, however, such systems are more than just rational tools; they contain elements of symbolism and rituals, and particularly so in high-contextual cultures, of course. During meetings, handshakes are acceptable. Turkish businessmen dress the same way as western collogues. Women should pay a special attention to their appearance and avoid short skirts or bright colors (Hoecklin, 1995). Manners include such details as to be careful about hand gestures (even though Arabs ‘talk’ a lot with their hands, as previously mentioned). Believers of Islam are sometimes referred to as ‘people of the right’) and bodily functions, such as nose-blowing, are down-played (there are paper tissues everywhere and they are highly used).

It is also considered impolite for people to expose the soles of their feet or shoes to those present (do not stretch your legs while sitting on the floor in somebody’s house — a common place to sit when there are many visitors). The offer to visit an Arab’s home should be accepted and the system of hospitality is based on mutuality. During negotiations, business decisions are slow. A western manager should not use deadlines because Turks can cancel agreements and contracts (Hodgetts & Luthans 1991). It is crucial to focus on financial gains and advantages of projects because it is the most important part of business for Turks. One reason for this could be the approach taken to inheritance and succession in the Turkish business firm. There are fewer written rules in this culture and organizational development techniques for stimulating interpersonal openness and feedback are natural there (Griffith et al 2000; Gosteland, 1999).

Thailand

The one thing the Thai are good at, however, is financial business management. Thai entrepreneurs “have an excellent mastery of financial levers” (Gosteland 1999, p. 63), and in their daily business dealing, they pay close attention to cash management. In order to always have cash available to be ready for any profitable deal that may turn up can lead a Thai to selling his or her goods at a lower price (even at a loss) in order to move money faster and even to borrowing money in a bank and then saving it in the same bank again to increase his or her assurance of access to ready cash, even if the bank is changing its credit policy (Gosteland 1999).

For Thais, no conflicts or misunderstanding is the main success factors. During negotiations, they value patients and obedience. As long as the Thais make money, they feel that time is on their side (Carroll & Buchholz 2000). On the other hand, thinking in terms of sales and financial outcome makes the Thais prone to short-term thinking. However, foreign firms trying to do business with the Thais should not think short term. A lot of time is involved in acquiring experience and cultivating relationships for an outsider. Laboriously established connections can easily break down. The point is not to work with the Thais in the sense of a complete strategic package, but accumulating trust, one step at a time (Dowling et al 1995; Davis, 1989).

Recommendations

In both countries, a special attention should be paid to religious traditions and values, Islam in Turkey and Buddhism in Thailand. To gain access to this divine reality there are many rules to follow for a Muslim and Buddhist. Religion becomes part of a daily life, and a visitor to the world who shows respect for the religion will gain a favorable reception almost everywhere. This means, among other things, refraining from drinking alcohol at social events and not exposing any kind of images, such as religious symbols, statues and so on. This also means that the visitor, whether a businessman or not, encounters a male-dominated society. Women are usually not part of the entertainment scene in the Muslim Arab and Buddhist worlds.

They carry on with their own social lives, and they are not involved in business with foreigners. Also, in both cultures, there is less concern with fashion in management ideas. Cultures vary in terms of how explicitly they send and receive verbal messages. This means that communication between Turks and Thais rely on hidden, implicit, contextual cues such as nonverbal behavior, social context and the nature of interpersonal relationships. To a foreigner, communication may even sound very inexact, implicit and indirect. There are many factors that may influence the climate of communication. Emphasis on words without context is quite confining to both cultures. Verbal accuracy is less important to Turks and Thais and giving attention only to verbal channels of feedback in a working relationship is, to them, inappropriate.

Bibliography

Barham K., Conway C. 1998, Developing business and people internationally: A mentoring approach. Ashridge Research.

Bartlett, C. and Ghoshal, S. 1999, Managing Across Borders: The Transnational Solution. 2nd edition, London: Ramsden House.

Brake, T., Walker, D. M., and Walker, T. 1995, Doing Business Internationally.Burr Ridge, IL: Irwin Professional.

Brislin, R. 1993, Understanding Culture’s Influence on Behavior. Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Carroll, A. and Buchholz, A. 2000, Business and Society: Ethics and Stakeholder Management 4th edn. Cincinnati, OH: South-Western Publishing Co.

Davis, S.M. 1989, Future Perfect. In Evans, P., Doz, Y. and Laurent, A. (eds) Human Resource Management in International Firms. London: Macmillan.

Dowling, P. J., Welch, D. E. and Schuler, R.S. 1999, International Human Resource Management, 3d edn, South West Publishing.

Gosteland, R.R. 1999, Cross-Cultural Business Behavior. Copenhagen: Copenhagen Business School Press.

Griffith, D. A., Hu, M. Y. and Ryans, J. K. Jr. 2000, “Process standardization across intra- and intercultural relationships”. International Business Studies, 31, pp. 303-24.

Hodgetts, R. M. and F. Luthans. 1991, International Management, Singapore: McGraw-Hill.

Hoecklin, L. 1995, Managing Cultural Differences: Strategies for Competitive Advantage. Wokingham, England: Addison-Wesley.

Hofstede, Geert. 1984, Culture’s Consequences, Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Keegan, W. J. and Green, M. S. 2000, Global Marketing 2nd edn. UpperSaddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Putti, J.M. (ed.) 1991, Management: Asian Context, Mc Graw-Hill.

Punnett, BJ. 1994, Experiencing International Business and Management 2nd edn. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Schneider, S.C. Barsoux. J.-L. 2002, Managing Across Cultures. Prentice Hall; 2 edition.

Steiner, G. A. Miner. J. B. 1986, Management Policy and Strategy, 3rd edn, New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc.

Sterman, J. D., 2000, Business Dynamics: Systems Thinking and Modeling for a Complex World, Irwin McGraw-Hill, New York.

Taggart, J. H. and M. C. McDermott. 1993, The Essence of International Business, Hertfordshire, England: Prentice-Hall.

Trompenaars, Fons. 1995, Riding the Waves of Culture, London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.