Introduction

The ability to speak two or more languages is very beneficial in the contemporary globalized world; it gives an individual the ability to converse with a wider range of people. People who can speak two languages are called bilinguals, while those who speak one language are called monolinguals. Based on these two terms, there are aspects of bilingualism and monolingualism. In addition to the social benefits of being able to speak to diverse groups of people, recent scientific studies show that bilinguals have some other advantages than monolinguals. Bilinguals have been found to have enhanced cognitive capabilities.

Therefore, the argument that bilinguals are smarter than monolinguals is a shift from the past understanding of bilinguals which considered command of second language as a significant hindrance to the intellectual development of learners. In this paper, I will use secondary data on auditory sustained selective attention task to demonstrate that bilinguals have some cognitive advantages as compared to their monolingual peers. The paper starts with theoretical assumptions, followed by the literature review, the data obtained and the analysis.

Statement of the Problem

For the most of the 20th century, there had been a universally acknowledged notion that bilingual learners’ abilities are impaired as compared to their monolingual counterparts. The understanding was that based on the way the brain of bilinguals functions. For instance, the brain system for two languages is active when the individual is using one language. Therefore, it creates a scenario where one system obstructs the other. This was the handicap the researchers of the 20th century dubbed as a hindrance. However, recent studies show that the same mechanism enhances the cognitive abilities of bilinguals. According to Bialystok et al, it leads to a situation where the brain is prompted to resolve the internal conflicts related with the active language at the time; this gives it an exercise that builds the cognitive muscles (242). Therefore, this paper aims at finding out whether this brain mechanism related to second language is a sign of handicap or a depiction of increased cognitive abilities.

Theoretical Assumptions

Based on the perspective of the competition, the theoretical assumption used in this paper is Inhibitory Control Model. The model has been one of key frameworks for understanding how the brain of bilinguals functions. According to the model, it assumed that bilinguals experience continuous competition which has been described as conflict interference in the lexical presentation of the languages (Shell et al. 2146). The lexical presentation is always active when the individual is reading, speaking and listening. Therefore, to overcome the competition, the brain recruits a control, a function that inhibits the activation of the language that is being used at the time. The inhibition process is not domain-specific; instead, it is rather general and it transfers to other functions that are not necessarily linguistics one (Shell et al. 2147). This leads to clever manipulation of the brain that is also manifested in the executive control. This forms the basis for explaining why bilinguals have been found to be smarter in executing some functions compared to their counterparts. As such, bilinguals are likely to exemplify enhanced capabilities in solving mental puzzles which indicates their enhanced executive function control.

Literature Review

There are different tasks that have been used to measure the cognitive abilities for bilinguals and monolinguals; in most cases they have focused on executive function (EF) control. The tasks have led to the assertion that bilingualism has an effect on the brain that leads to improvement of the cognitive skills that are not related to language. The assertion is supported by various researches that have shown efficiency, development and cognitive abilities gap based on the number of languages an individual can speak; for example, the acquisition of second language makes the brain develop control mechanism during speech.

The issue of language acquisition and its effect on the cognitive development has raised different opinions among researchers striving to determine whether bilingualism amplifies cognitive abilities or hampers them. As such, over time, there have been many studies that have been carried out to examine the positive or negative effects of bilingualism from birth to adulthood. Besides, there have been different assumptions related to the implication of bilingualism as provided in the literature in the 20th and 21st century. For example, Baker related bilingualism to mental deficits and social problems (17). There were researches that supported Baker’s reasoning about the bilingualism that children who spoke two languages were less intelligent that those who spoke one language. However, studies carried out in the 21st century have different implications that in fact show that bilinguals in fact excel one language speakers at fields where the ability to perform skills that require greater control matters the most.

In an experimental study, Kovacs and Mehler studied 20 children aged seven months raised by monolinguals since birth and compared them with 20 infants of the same age raised by parents who were bilinguals (6557). The research involved a task aimed at examining their cognitive abilities by using a switch task that entailed speech cues. The children were more or less equal in regard to factors that could bring variations such as the age, gender, and socioeconomic status for the parents; this was done to avoid disparities which may compromise the results (Kovacs and Mehler 6557). The criteria for children considered bilinguals included those with parents who addressed them consistently in different native languages. The children were tested on the tasks that required the use of the EF; the assumption used for the study was that if the bilingual participants enhances EF, then they were to outperform monolinguals in the tasks that required the use of EF.

Different speech cues were used to test the children and a visual reward was given (Kovacs and Mehler 6557). The reward was a looming puppet that appeared on particular side of screen whenever the children were prompted. In the course of the test, it was established that the children learned how to respond to the visual cue in the anticipation of reward popping out of the screen. However, the bilingual infants suppressed their looks to the required location and learned the pattern for the prompt unlike monolinguals (Kovacs and Mehler 6559). The conclusion from the study was that the two languages contributed to the enhancement of the cognitive control system for bilinguals.

Despite the implication of the cognitive abilities as established in the Kovacs and Mehler study (6556-6560), there are domain-specific tasks monolinguals are generally better at. This could be an indication of systematic deficiency of bilinguals. For example, in the process of word generation, this factor happen to be a disadvantage for bilinguals’ academic performance. In terms of the receptive vocabulary, both the bilingual adults and children have been found to control smaller vocabulary compared to monolinguals; for instance, in a task that involves naming pictures, the former were found to be slower and were not as accurate as the latter (Bialystok et al. 246). These are factors of neuropsychological measure of how the brain functions. However, this pattern of the brain function among monolinguals is contrasted by the abilities of bilinguals in the executive control if the children match based on different background factors. According to Bialystok, executive control is composed of a set of cognitive skills (4).

Studies related to increased cognitive performance of bilinguals in solving conflicting tasks better than monolinguals were also established in a study conducted by Byers-Heinlein and Lew Williams (95). In the study, 8 years old children were involved in different nonverbal task were to solve. Some task included perceptual distraction and other did not have any form of interference. The results of the study were twofold: where there was no perceptual interference, the results were comparable; however, in task where distraction was introduced, bilinguals performed better than monolinguals. There are also other studies that have shown that bilinguals are better off than monolinguals in tasks that are relatively difficult. For example, in directional Simon Task, bilinguals have been found to outperform monolinguals when there are elements of increased monitoring and switching than in cases where there are simpler conditions (Bialystok et al. 246).

From the literature review, it can be inferred that there are differences in the cognitive abilities between monolinguals and bilinguals. Also, it has been shown that in the issues that require executive controls, bilinguals tend to outperform monolinguals. This is the case for both adults and children aged 7 months and more. This body of knowledge brings a new perspective on cognitive abilities associated with bilinguals and sets the ground for more researches and data synthesss in tasks involving monolinguals and bilinguals.

The Data

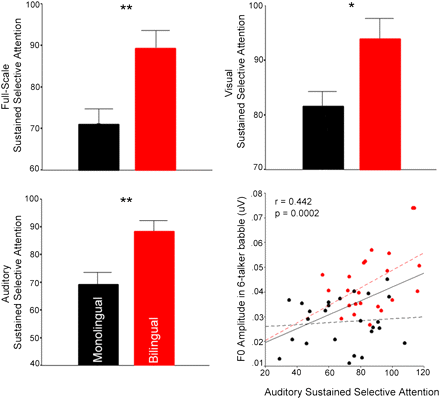

Most of the studies reviewed have focused on the task performance. However, for this, I will analyze the cognitive ability based on the dimension of attention. The executive function tested in this case is related to the various tasks that are associated to the general brain performance. However, for this paper, the focus is on how bilingualism affects the brain especially in the cortical regions that deal with the processing of the language functioning. The data was collected to test auditory sustained selective attention. The data to be analyzed is retrieved from Krizman et al. (7879). See figure 1 below for the graphical representation of the data.

Analysis of the Data

The findings from the auditory test and the sustained selective attention showed that bilinguals had practical benefits in the sub-cortical representation of the fundamental sound frequency and in the attention abilities related with the strength of the frequency in the multitalker babble. In a quiet medium, the results were different. This task was sound-based unlike the previous studies that have focused on the other activities. Nevertheless, the results are consistent with those of Bialystok et al. (246) and Kovacs and Mehler (6559). They depict bilinguals having some advantages over monolinguals in cases where the aspect of multitasking is introduced. The reasons for the benefits are scientific and relate to how different parts of the brain interpret meaning from either sound or task. The present findings add to the existing body of knowledge that associated bilinguals with some form of benefits in solving conflicting tasks and depicts the organization of the brain for the people who speak two languages.

There are logical explanations that are attributed to the brain organization of the bilinguals; the explanation is based on psycholinguistic studies that apply different tasks such as cross language priming. This is explained as the situation in which a word in one language can be used to facilitate the acquisition or retrieval of a semantically related word in another dialect. Also, the explanation can be related to lexical decision in which an individual who has ability of speaking two or more languages can decide whether some letters constitute a legit word in one of the languages. This denotes the influence of one language on the development of the other. It is important to note that this is a wide field of linguistics and it faces challenges of the study when the bilingual uses languages that may have no lexical relations in the syllables (Bialystok and Luk 397). For the case of the auditory selective attention, it shows a similar concept in which bilinguals can identify varying sound frequencies better than monolinguals.

Similarly, based on the psycholinguistic studies, the findings can be explained on the perspective of how musicians encode sounds. According to Krizman et al., musicians have been found to have cognitive processing abilities similar to those of bilinguals (7880). This has been related to the neural encoding of sound when the music in presented in competing manner. Therefore, bearing in mind that bilinguals’ minds functioning is just like music training, i.e. it is a way of sensory enrichment, which translates to gains in cognition, bilinguals can show enhanced syllable recognition compared to monolinguals. The results also affirm the issues that bilingualism is related to improved metalinguistic awareness, in which the speaker can realize sound as a system that is able to be explored. However, it is important to note there are certain limitations that bilinguals have to endure as was the case of the study by Leonard et al. (3287) that established that bilinguals were outperformed by monolinguals in the word generation.

Also, in studies that have sought to test the cognitive abilities of bilinguals it has been shown that bilingualism enhances visual spatial skills analogical reasoning, concept formation, creativity and foster classification. The findings can be related to the case of the auditory selective attention because the functions deal with executive control. However, Bialystok and Luk pointed out that for the benefits associated with the cognition to be realized, there is a certain level of fluency in the languages that should be achieved (399). For example, Kovacs and Mehler (6557) asserted that cognition skills are mediated by the level of fluency in the languages. The implication for this being a certain level of fluency a child is to achieve to match a level of two language speakers. However, this assertion has been disapproved by the recent studies that show differences in executive control for children aged less than a year. For instance, the study by Kovacs and Mehler that focused on the children aged seven months (6556-6560).

The findings can be understood on the basis of Inhibitory Control Model in which cognitive functions are enhanced through the various brains mechanisms. The model formed the theoretical assumption of the paper and it is related to the concept of language switching. As per the model, Shell, Linck, and Slevc claim that“the people with higher scores domain general inhibitory control tasks tend to do better in the language switching” (2148). Despite the current findings that support the premise of bilinguals having better cognitive skills that monolinguals, there are contradictory findings on how the inhibitory control resolves competition and subsequently leads to bilinguals’ benefits. There have been arguments that the evidence presented is based on correlations and is subject to different explanations.

For example, in relation to the education levels of the people having been tested, the motivation at the time of tests and biases that relate to conditioning of study participants to respond in a particular manner. Even though this is valid school of thought that may bar the absolute conclusion that bilinguals are smarter, the argument needs to be put in the context of the studies that have endeavored to pair subject during the studies based on their backgrounds. Also, as found out in the study carried out by Kovacs and Mehler on children who were aged seven months old, the issue of bias from conditioning does not arise (6550-6557). Also, children brought up talking two languages have been found to select words correctly when they have just started learning to talk, but they can borrow words from either language demonstrating the lexical decision-making process. It is more interesting that the benefits are not confined to acoustic properties of language; the ability to regain attention among bilinguals is higher as compared to monolinguals.

Conclusion

For the current study, the main area of focus was cognition and how it is better exemplified in bilinguals than in monolinguals. Therefore, the literature and tasks that were drawn primarily focused on answering the question ‘why bilinguals are smarter?’ As evidenced from the findings, bilinguals were found to outperform monolinguals in tasks that required the application of the executive function of the brain to solve conflicting issues. As far as executive control supports multitasking, high thought level and the sustained attention are concerned, it can thus be concluded that bilinguals are smarter than monolinguals. It is worth noting that, unlike the neuropsychological measures in which monolinguals may show better results, the executive control function of the brain plays a great function in the academic achievement among the children. Despite the conclusions, it is also important to note that monolinguals playing the second fiddle to bilinguals is not an exclusive study when it comes to different activities; instead, the study centered on the domain of cognition that deals with executive control. Therefore, there is need for further comprehensive investigations that consider other domains of the brain.

Works Cited

Baker, Colin. The care and education of young bilinguals. Clevedon, England: Cambrian Printers Ltd, 2000.

Bialystok, Ellen, and Gigi Luk. “Receptive vocabulary differences in monolingual and bilingual adults.” Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, vol. 15, no. 2, 2008, pp. 397-401.

Bialystok, Ellen, et al. “Bilingualism: consequences for mind and brain.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences vol. 16, no. 4, 2012, pp. 240-250.

Kovács, Melinda, and Jacques Mehler. “Cognitive gains in 7-month-old bilingual infants.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, vol. 106, no. 16, 2009, pp. 6556-6560.

Krizman, Jennifer, et al. “Subcortical encoding of sound is enhanced in bilinguals and relates to executive function advantages.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 109, no. 20, 2012, pp. 7877-7881.

Leonard, Matthew, et al. “Spatiotemporal dynamics of bilingual word processing.” Neuroimage, vol. 49, no.4, 2010, pp. 3286-3294.

Shell, Alison, et al. Examining the role of inhibitory control in bilingual language switching, 2009. Web.