Background

In the history of Australia, the industrial relations system has been based on the determination of the employees wage rates. In fact, the workplace relations system embraced by Australia was dissimilar from those adopted by developed nations. The system often incorporated enforced arbitration.

Under the Australian workplace system, every workforce had the lowest remuneration payment rate as well as further employment provisions that were defined in the awards. Despite all the stipulations, the last few years saw the emergence of three key legislative amendments in workplace or industrial relations system of Australia. The legislative changes included the 2009 Fair Work Act, the 2008 Act on Transition to Advancement with Equality, and the 2005 Work Choices Bylaw (AWR).

From the fiscal year 2006 to the financial year 2008, the 2005 Work Choices Act also known as the Amendments on Workplace Relations governed each person who was working in a company operated under the Territories, Victoria, or Commonwealth authorities. In total, it added up to 80.0% of employees in Australia. Besides, every worker operating under the Work Choices Act had his or her employment conditions and remuneration package managed by the Australian Commission of Fair Pay (ACFP).

Peetz (2007) considered the Act as the most radical amendment in the Australian Industrial Relations (IR) legislation. The major amendments in the legislation incorporated the decrease in the total necessary work status to five conditions, the inclusion of AWAs (the Australia Workplace Agreement), and the eradication of “No Disadvantage Test.”

Nonetheless, the 2009 Fair Work Act sets out the most recent amendments in the Australian workplace conditions. The novel bylaw became enforceable since July of the fiscal 2009. In fact, this bylaw aimed at restoring the workers negotiation influence as well as safeguarding the workforce based on their good faith negotiation condition.

The transition from “Work Choices to “Fair Work Australia”

In terms of employment protection, Australia was ranked number twenty-two out of all the twenty-eight OECD nations prior to the implementation of the Work Choices Act. After the Act was enforced, the country dropped to number twenty-five in matters relating to the protection of employment. In fact, the reason for the drop in position initially held was loss in workforce choices and lack of free bargaining power.

For example, the Australian workers were compelled by their employers to sign the AWA (the Australian Workplace Agreement) as a service or employment provision. Furthermore, based on the operational reasons such as technological, structural, or economic, the employees were sacked without notice (Workplace Express, 2006).

As a result, the Australian employers had every reason to re-hire workforces and compel them to work under poor conditions while paying them very low wage rates, as was witnessed in Cowra Abbatoir case.

Whereas the Australian administration asserted that the Work Choice could increase the number of employment opportunities, augment the wage rates, and improve the economic status, the Act generated negative impacts on the Australian economy. For instance, Work Choices Act hardly solved the economic challenges that Australia faced during that time. The challenges encountered by Australia are as listed and discussed below:

Improving the standards of living

In the previous years, the Australian Commission of Fair Pay only offered nominal wage increment to the employees and declined to award salary increase in the fiscal 2009. Besides, the one and half years gap amid the ACFP initial decision and the Australian Commission of Industrial Relations final decision implied that the actual earning rate for the employees on the grant salary had to decrease (Workplace Express, 2006).

After the ‘No Disadvantage Test’ was abolished, the grant salary formed the foundation for the employment settings and salary rates for any worker employed under the joint accord and the AWA. Employees who shifted to AWAs from the joint accord became worse off since the state hardly fulfilled the salary increment pledge it proposed to offer under the Work Choices Act (Peetz 2007).

Provided the workers unions represented any worker employed under the joint accord stipulated in the Work Choice Act, such an employee was bound to get averagely 3.90% or 3.60% annual salary increment. However, workers who signed the Australia Workplace Agreement only received annual salary increment of 2.20% (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2009).

This implied that the negotiating power of employees was determined by their unity, though the Work Choice Act reduced the intervention by third parties and the workforces’ solidarity. The total income of employees significantly declined due to salary blow caused by Work Choices.

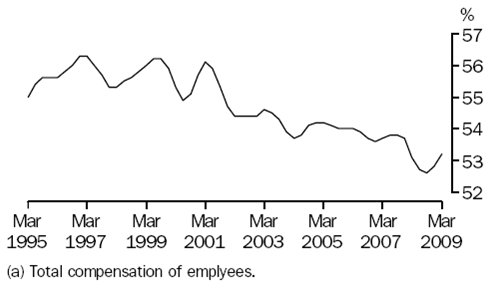

Total national income accruing from wages

Sourced from ABS (2009)

From the diagram above, the overall salary share factor declined to 53.30% from 54.20% in the fiscal 2008 and 2005 respectively. When compared to the 1983 figure of 61.10%, these levels are considerably low. During Howard reign in the fiscal 1997, the country recorded 56.20% stability rate though a stable decline was reported between the fiscal 2005 and 2008. However, the revenue-profit allocation factor improved to 26.50% from 22.70% in 2008 and 1997 (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2009).

The protected award stipulations in the AWAs were also reduced including reductions in rest breaks, public holiday wages, fiscal allowances, overtime loading, penalty rates, and shift-work loading. Thus, Work Choices was not friendly to the families as it denied them annual leave, and paid maternity leave. Reductions in the employment conditions, salary packages, and increased unfair dismissal implied that workers could not pay debts and mortgages hence causing monetary catastrophe in the Australian families.

Conquering the shortage of skills

The unfair employee discharge laws were introduced by the Australian administration in the fiscal 1994. The hiring companies by then claimed that provided there were no penalties imposed on the employees, more workforces could be employed if the employers desired to sack those already hired.

However, the employment rate grew to 3.90% in 1994 after the introduction of the unfair dismissal Act (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2009). A 2.60% decrease in the growth of employment was reported after the abolition of the unfair discharge bylaws. Instead of creating additional jobs, the abolition of this Act curtailed the employment growth rate. The dearth of skills was equally not reduced by the Work Choices Act, which attempted to encourage school-founded apprenticeship.

In fact, increasing the number of educated employees hardly translated into augmenting the quantity of labour supply. The major setback associated with lack of skills and knowledge is how an employment opportunity attracted workers. Hence, the employment conditions and better wage rates are part of the resolutions to the emerging challenges, but Work Choices hardly incorporated these measures.

Enhancing the productivity of Australia

With respect to production, it is difficult to prove that the productivity of Australia might be increased through decentralized salary fixing systems.

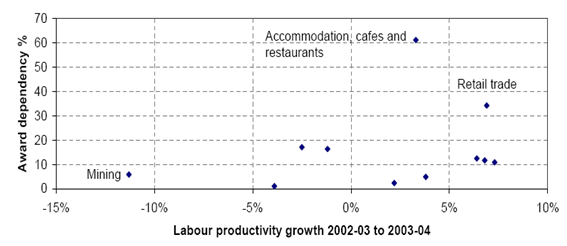

From the above diagram, it is clear that the productivity of labour will increase with increment in the level of award reliance. This implies that the phenomenon of increasing the economic productivity of labour is not yet achieved (Peetz, 2007). In the fiscal 2006, out of thirty-two nations, it was reported that the growth of labour productivity in Australia could be ranked number twenty-three (Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, 2004).

The 2009 Fair Work Act: The Provisions and Key Features of the Act

After the realization that the Work Choices Act generated negative economic impacts, the Australian government enacted the 2009 Fair Work Act to denote the amendments made in the industrial relations bylaws. Starting from July 1, 2009, the newly enacted bylaw had become operational and enforceable.

The Act was mainly aimed at restoring the workforce negotiation power while provisions were incorporated to ensure that the good faith negotiation and workers needs are generally protected. The two major amendments that continued from the 2008 Act on Transition to Onward with Equality included the “No Disadvantage Test” institution and AWAs eradication.

Further provisions made in this Act included setting out all the employment circumstances and workers salaries under the Modern Award or under an agreement instigating from the financial year 2010. Moreover, every accord was expected to go through the “No Disadvantage Test” called BOOT (Better-Off-Overall-Test). The provisions were supposed to warrant that all employees working under a particular accord were generally well off compared to those incorporated in the Modern Award.

The key features of the 2009 Fair Work Act included:

- Three agreements.

- Instituting unfair dismissal.

- Offering negotiation assistance to the employees.

- Enhancing the protection or safety net.

- Establishing three Australian Fair Work Institutions.

The 2009 Fair Work Act Processes

Instituting unfair dismissal

It was impossible to make unjust firing claims except when the employee worked for a company with more than one hundred employees for approximately twelve months. This condition was under the provision of Work Choices. More than 98.0% of all corporations listed under the private sector were affected following the elimination of the protection of unjust discharge.

However, unjust sacking bylaws protected numerous circumstances and several employees from dismal after its reinstatement under the 2009 Fair Work bylaw. Currently, it is possible for a worker to make claims for unjust firing if it was not a case of sincere sacking, not in harmony with the code of just firing, and irrational, unjust, or harsh (Fair Work Australia, 2010).

In fact, a minimum of twelve months in service in a small firm and six months in a large firm enables them to submit claims. A claim can be made if a small firm is defined as a business without more than fifteen permanent employees unlike in the previous Work Choices that stipulated one hundred permanent employees. Nevertheless, the employees cannot make claims if the revenue is more than 108,250 dollars and are not covered by the Modern Accord, Award or if they have worked for less than the stated periods.

Therefore, a corporation must provide genuine reasons why the employee might be at jeopardy of being sacked in order to offer further protections for the employees. Hence, this intention must be established on the employee’s capability to complete the assignments. At least operational reasons and verbal warnings must be provided to the responsible authority (Fair Work Australia, 2010).

The accord in Act

The human resources who are out of the contemporary reward coverage will have their situation for service and expenses set in one of the three accords under the 2009 Act of Fair Work. According to Fair Work Australia (2010), the agreements include Greenfields Accords, Multi-enterprise Accords, and Single-enterprise accord.

The Modern Awards

The mainstreams of Modern Awards have provisions for transition that are distributed across five years plan commencing from the year 2010. Therefore, in phasing will occur at twenty percent. Conversely, there will be a progressive phase-in the reduction if the grown-up earnings charge under Modern Award is lower than the earnings in the pre-existing award.

Thus, employees in similar industries and profession could be on a diverse payment arrangement. Nonetheless, the reduction in the disposable workers pay is not the purpose for introducing the modern award as specified by the 2010 Australian Fair Work.

The government has initiated orders in the take home earnings to make sure that payment reduction does not occur. In any case, the employees’ experience reduction in their pay for equivalent refurbished periods, the union, or the employee can justify this in script to the Australian Fair Work. Thus, consideration of whether the reduction is insignificant or minor and if the reimbursement has been made to the workers is executed by FWA (Fair Work Australia, 2010).

The agreements for enterprise negotiation

The organization needs to pass the Better-off-Overall-Test, ensure there are procedures for row resolution, contain suppleness and conference clauses, and follow the pre-approval procedure for the Australian Fair Work to pass the Enterprise Negotiation Accord.

The recent McDonalds high profile case is a significance of the scrutiny of Enterprise Negotiation Accord by the Australian Fair Work. The Australian Fair Work declined to pass the Enterprise Negotiation Accord even though the Superstore Distributive and the Allied Staff Union’s endorsed McDonalds Australia Enterprise Accord 2009.

In support of the FAW, McKenna, an administrator, claimed that McDonalds failed to meet the pre-approval procedures and all other required standards. The Australian Fair Work then argued that McDonalds botched to give all the employees a duplicate of the NES and the notification about polling on the accord.

Another rejection of the Enterprise Negotiation Accord was due to an effort by McDonald to compensate the Queensland employees with lowest state earnings for loss of numerous circumstances and disbursing the personnel to work in Territories with no fine charges thus, diminishing their hourly salaries by 20.0% (Fair Work Australia, 2010).

There is no warranty that employees are better off while moving from one accord to another. However, Enterprise Negotiation Accord ought to pass the BOOT. In fact, the agreement will make sure that under the Enterprise Negotiation Accord the employees are hardly worse off compared to the Modern Award. Actually, through the power of negotiation, when moving from one agreement to the other, several employees their mislay prerogatives and pay (Fair Work Australia, 2010).

The Institutions of Australia’s IR system and their roles

The 2009 Fair Work Act established three Industrial Relations Institutions in Australia. The institutions included:

- The Federal Magistrates and Federal Court Fair Work Divisions.

- The Fair Work Ombudsman Office.

- The Australian Fair Work.

The 2009 Fair Work Act established the Fair Work and the General Divisions. The dissections were charged with accountability of settling rows that concern letdown to adhere to NES stipulationsor the rewards. The Divisions equally practiced the court powers involving claims of $20,000 for unjust firing.

The institution also uses proceedings from the courts in enforcing responsibilities and constitutional rights. Finally, the Australian Fair Work, which replaced various agencies namely the Workplace Authority, AFPC, and AIRC, is a sovereign entity expected to act fairly, efficiently, and swiftly. This institution adjusts and stipulates the nominal pay rates, intervenes and resolves rows, orders for good faith negotiations, endorses unjust discharge and employment agreements, as well as appraises awards.

The implications of the Act

The Awards of the present

Despite being initiated in 2010, most contemporary rewards have setting that are intermediary and which are scattered across a phase of five years. Given that the launch happens in a 20.0% growth, the HR and planners will be obliged to adjust the hourly wage rates due to the progressive phasing in. According to Fair Work Australia (2010), planners and HR managers will have to make different payment schedules for employees in one industry or similar occupation.

The EBA (Enterprise Bargaining Agreements)

The 2009 Fair Work Act requires the EBA to be carefully scrutinized more than it was previously done. The managers and planners are obliged to pass the BOOT, ensure that there are processes for dispute resolutions, there are consultation and flexibility clauses, and all the pre-endorsement procedures are duly followed.

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), 2009, Australian national accounts: national income, expenditure and product, cat No. 5206.0, Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra, Australia.

Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (ACCI) 2004, ACCI submission–2005 safety net review, ACCI, Canberra, Australia.

Fair Work Australia 2010, Fair work Australia, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra. Web.

Peetz, D 2007, Assessing the impact of work choices one year on, Industrial Relations Victoria, Melbourne. Web.

Workplace Express 2006, “Harper downplays impact of minimum wage rise, looks for jobs growth,” Workplace Express.