Analysis

Body art in the form of tattoos and piercing is widely discussed by the public because many persons have different visions of this phenomenon while referring to their ideas and personal experiences. The qualitative data received with the help of working with the focus group has been analyzed according to the principles of the Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) to interpret the participants’ experiences related to their vision of such body art as tattoos and piercing.

The main purpose of the IPA is to provide information on how participants can interpret the meaning of body art in their life with references to the fact that they have or had tattoos and piercing (Palmer, Larkin, de Visser, & Fadden, 2010, p. 100). The epistemological position related to the participants’ experience is based on the idea of meaning-making because it is necessary to find answers to the question of how individuals make meaning about body art. According to the stated epistemological position, it is assumed that individuals make sense of such a phenomenon as body art while referring to their personal negative or positive experiences.

To answer the research question, the received data was coded with the focus on making exploratory commentaries (Tomkins & Eatough, 2010, p. 245). Much attention was paid to describing the participants’ actual vision of body art and its meaning in descriptive commentaries and to analyzing the participants’ interpretation in the abstract commentaries. Commentaries of the linguistic aspects provided the information about the individuals’ emotions associated with perceiving their own and tattoos and piercing, the body art of their partners, and the artists represented on bodies of the other people (Appendix 1; Palmer et al., 2010, p. 101).

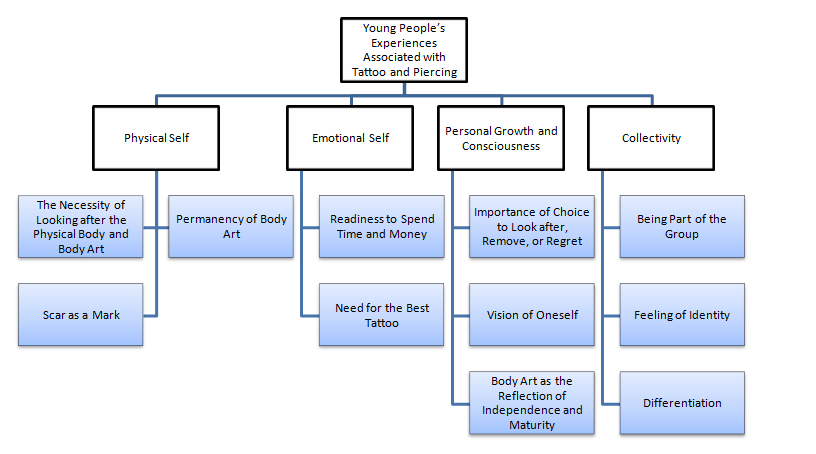

As a result of coding the transcript, four master themes as Physical Self, Emotional Self, Personal Growth and Consciousness, and Collectivity were identified (Appendix 2). It is important to note that the participants of the focus group demonstrated the readiness to discuss their tattoos and piercing from the perspective of their connection with the physical body. Thus, tattoos and piercings were perceived as part of the person’s physical body and appearance. The participants also focused on the discussion of the role of emotions, desires, and intentions while choosing body art, deciding to do a tattoo or piercing, and while speaking about their tattoos and piercing.

The other revealed master theme is Personal Growth and Consciousness. The participants actively discussed the role of body art in changing their visions of self. Furthermore, the participants also pointed at the changes in their visions of the other people and their understanding of being a part of the group. Thus, one more identified master theme is Collectivity (Appendix 2). Although perceptions of the body art are often different, young people make meaning about tattoos and piercing while focusing on such four perspectives as physical, emotional, conscious, and collective; thus, the young people focus on the vision of the physical body changed with tattoos and piercing, on emotions and intentions beyond the decision, on the vision of self as a personality, and the vision of self as the part of the group.

Physical Self

This master theme is originated from such superordinate themes as Permanency of Tattoos and Piercings, Necessity of Looking after the Physical Body and Body Art, and Scar as a Mark. The participants did not demonstrate equal participation in the discussion of all these themes, and each of them focused on discussing one or two of these themes.

Permanency of Tattoos and Piercings

Permanency of the modern body art can be discussed as questionable because of the modern technologies which allow removing not only piercing but also tattoos. This possibility to get rid of tattoos and piercing can influence the people’s decision and their meaning of the body art because of providing a kind of choice while regarding the physical appearance (Randall & Sheffield, 2013, p. 112). Thus, David points at the fact that “the permanent nature of tattoos have changed somewhat” (Appendix 1). This idea is reflected in the discussion of Jo’s experience with taking out the nose piercing (Appendix 1). It is easier today to get rid of tattoos and piercing, and young people refer to the questionable permanency of body art while deciding to do tattoos or piercing.

The necessity of Looking after the Physical Body and Body Art

Discussing the issue of care, the participants focus on challenges associated with looking after body art. Four participants accentuated the necessity of care about body art because of possible infections, traumas, and discomfort. Jo states that “piercing does take a lot of kind of care” (Appendix 1). Mandy supports the idea of claiming “if I look after it properly, then surely it shouldn’t be a problem” (Appendix 1). Thus, to look after the body art means to understand the physical self and demonstrate not only the difference but also responsibility for the health (Quaranta et al., 2011, p. 775). The other side of the problem is the readiness to get rid of body art instead of looking after it. Infections caused by the absence of care make people think about physical discomfort. Thomas explains the situation, “I was just like ‘I’ve got no chance of carrying on with this’” (Appendix 1). The aesthetic nature of body art is not discussed when people have problems with healing holes or scars.

Scar as a Mark

The concept of a ‘scar’ was frequently mentioned by the participants in their discussion of the physical aspect of the body art. The risk of scarring is discussed by Rachel who notes that it is “something that you would have considered when choosing” (Appendix 1). Tattoos can be discussed as the scars, as it is stated by Jo who is ready to scar the body “for life” (Appendix 1). Moreover, scars from a piercing can change the appearance significantly. Removing the piercing, people view scars differently, for instance, Thomas points at the ‘value’ of scars (Appendix 1). The risk of scarring provokes the active discussion of the role of physical appearance and its association with body art because a scar can be discussed as a reminder of a person’s wrong choice (Anastasia, 2009).

Emotional Self

The master theme is based on the discussion of such superordinate themes as Readiness to Spend Time and Money and Need for the Best Tattoo. These themes are grouped according to the participants’ desires, motives, emotions, and intentions reflected in their speech, and they should be analyzed as interconnected.

Readiness to Spend Time and Money and Need for the Best Tattoo

The desire to have tattoos and piecing cannot be challenged by such issues as time and money. Thus, David claims that people “don’t think about money” (Appendix 1). This idea is reflected in Jane’s words, “I think I’d rather spend thousands and get a nice one to be fair” (Appendix 1). While describing her experience, Jo states that it was “certainly a large a large amount of time” to do the body art (Appendix 1). From this point, time and money do not influence the persons’ decision, and the origin of the decision is a desire to have body art (Heywood et al., 2012, p. 52). Quality of the tattoo or piercing and the reputation of the master are more important factors in comparison with the time and money aspects. Jo emphasizes that it is necessary to “do a lot of research into the person” while seeking the master (Appendix 1). The focus on the master and quality is important to make the responsible decision and avoid problems (Mayers & Chiffriller, 2008).

Personal Growth and Consciousness

The master theme is associated with such superordinate themes as Importance of Choice to Look after, Remove, or Regret, Vision of Oneself, and Body Art as the Reflection of Independence and Maturity. These themes are connected, and the most important one to explain the young people’s meaning of body art is Changes in the Vision of Oneself.

Vision of Oneself

The participants are inclined to discuss tattoos and piercing as the reflection of their vision of themselves. This vision can change with age, and body art helps to focus on these changes. Thus, changes are observed in decisions on tattoos and piercing and in the persons’ visions of their independence and responsibility (Mayers & Chiffriller, 2008). Furthermore, body art becomes perceived as associated with personality. For instance, Mandy states, “my tongue piercing is part of who I am” (Appendix 1). That is why body art is the physical demonstration of the individual’s vision of oneself.

Collectivity

This master theme is associated with such superordinate themes as Being Part of the Group, Feeling of Identity, and Differentiation. To understand the nature of young people’s vision of themselves as a group, it is necessary to focus on the discussion of two themes: Being Part of the Group and Feeling of Identity.

Being part of the Group and Feeling of Identity

Having the piercing or tattoos, a person perceives oneself as a member of the group. The feeling of personal identity changes with the focus on the idea of collectivity. Discussing people with the body art, Thomas states, “I’m one of these people” (Appendix 1). Thus, his tattoos provide him with a feeling of identity and belonging to a unique group. The participants also accentuate that they discuss people with body art as more attractive because of the focus on likeness (Appendix 1; Heywood et al., 2012, p. 53). Persons with body art are discussed as the impressive community which attracts because of their internal likeness and difference from others (Quaranta et al., 2011).

Summarising the findings, it is possible to state that young people make meaning about tattoos and piercing while focusing on the physical body, on the emotional component, on the idea of the personality’s development, and on the idea of belonging to the community. Those young persons who have the body art focus on the right of the other people to have different visions of tattoos and piercing, but being the ‘part of the group’, they are inclined to accentuate the role of care, the risk of infections and scars, the role of the quality of the body art, the vision of oneself as independent and responsible, and the feeling of identity. Body art serves as a kind of individual expression and emphasis on personal differences.

Reflexive Analysis

Reflexivity as the ability to evaluate oneself and the personal impact on the research is important to be followed in qualitative research because reflexivity can provide answers to the questions about the research’s scope, focus, assumptions, and limitations. According to Shaw, the researcher’s vision influences all the stages of qualitative research, including the collection of data, interpretation, and analysis (Shaw, 2010, p. 234). That is why it is important to focus on reflexivity to avoid biases in the discussion of findings.

Focusing on personal reflexivity, it is important to note that my subject position influenced the research process partially because I am interested in discussing the issue of body art and people’s motivations to do tattoos and piercing. Thus, coding the data and identifying themes, I focused on the themes which can explain why young people decide to do tattoos. I was also interested in the issue of unexpected challenges associated with body art and focused on the theme of hygiene and care in the research.

While discussing the epistemological reflexivity, I should state that I had a particular epistemological position and focused on the idea of meaning-making while referring to the young participants’ experiences. Thus, I assumed that young people with the body art saw themselves as the specific group and focused on this limited area while prioritising the themes. From this point, the discussion of the participants’ other experiences and visions can contribute to further research on the topic.

References

Anastasia, D. (2009). Living marked: Tattooed women, embodiment, and identity. Humanities and Social Sciences, 69(9), 3759-3770.

Heywood, W., Patrick, K., Smith, A., Simpson, J., Pitts, M., & Richters, J. (2012). Who gets tattoos? Demographic and behavioral correlates of ever being tattooed in a representative sample of men and women. Annals of Epidemiology, 22(1), 51-56.

Mayers, L., & Chiffriller, S. (2008). Body art (body piercing and tattooing) among undergraduate university students: “then and now”. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 42(2), 201-3.

Palmer, M., Larkin, M., de Visser, R., & Fadden, G. (2010). Developing an interpretative phenomenological approach to focus group data. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 7(2), 99-121.

Quaranta, A., Napoli, C., Fasano, F., Montagna, C., Caggiano, G., & Montagna, M. (2011). Body piercing and tattoos: a survey on young adults’ knowledge of the risks and practices in body art. BMC Public Health, 7(11), 774-789.

Randall, J., & Sheffield, D. (2013). Just a personal thing? A qualitative account of health behaviours and values associated with body piercing. Perspectives in Public Health, 133(2), 110-115.

Shaw, R. L. (2010). Embedding reflexivity within experiential qualitative psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 7(3), 233-243.

Tomkins, L., & Eatough, V. (2010). Reflecting on the use of IPA with focus groups: Pitfalls and potentials. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 7(3), 244-262.

Appendices

- Appendix 1: The Annotated Transcript

- Appendix 2: The Thematic Map

Appendix 1: The Annotated Transcript

Appendix 2: The Thematic Map