Mary Flannery O’Connor (1925-1964) is one of the greatest American short-story writers, a novelist, and an essayist. She wrote in the Southern Gothic style, portraying her native Georgia and the other Southern States. Among the themes raised in her books were religion, moral decay, family, and human decency.

Read the full Flannery O’Connor’s biography prepared by our editorial team to find out more!

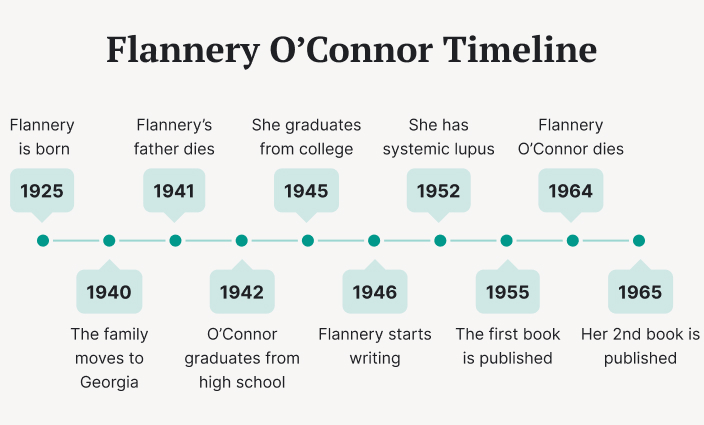

📈 Flannery O’Connor: Timeline

Below is the timeline of Flannery O’Connor. It reflects the most important events of the writer’s life.

👪 Flannery O’Connor: Early Years

Mary Flannery O’Connor was born on March 25, 1925. She was the only child in a Roman Catholic family of Irish descent. Her father was a real estate appraiser. She lived in Savannah, Georgia, until her adolescence. In 1931, she was admitted to St. Vincent’s Grammar School. By the fifth grade, she was transferred to Sacred Heart Grammar School for Girls.

Flannery spent more time with books than friends, even though her relations with other girls were amicable.

Unfortunately, Edward Francis O`Connor, the father, had lupus erythematosus, which got worse in 1938. Thus, the family moved to rural Milledgeville. It was her mother’s homestead when she was a child. So, they lived in the old mansion with Flannery’s aunts, Mary and Katie, who never got married. Her father came home only on the weekends, but Flannery seemed to enjoy the new place.

In the same year, Flannery went to the experimental Peabody School. It was too progressive, with low stress on the classics, as O’Connor remarked later. After a rapid aggravation, her father died in 1941. The writer avoided providing any revelations about her father, save the fact that she continued his legacy.

Peabody High School had close relations with Georgia State College for Women (presently, Georgia College & State University).

Flannery graduated from the College in 1945. The University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop helped her to master creative writing.

✍️ Career

The writing style of Flannery O’Connor was influenced by James Joyce, Robert Fitzgerald, William Faulkner, and Franz Kafka.

Her first short story appeared in 1946. Wise Blood, her first novel, appeared in 1952, exploring the “religious consciousness without a religion,” as explained by O’Connor. In 1955, her other short stories were collected in A Good Man Is Hard to Find and Other Stories. The eponymous story of the collection is regarded as her best-known work.

Her other fiction works include The Violent Bear It Away and the collection of essays, Mystery and Manners, that was posthumously published in 1969. The Complete Stories that appeared in 1971 won a National Book Award in 1972. This edition contained several stories that had never appeared in publications before.

O’Connor’s works are notable for the seeming mismatch of devout Catholic worldview with the grim, ironic writing that commonly features appalling acts of violence and unlikeable and vicious characters. The prevalence of brutality in her literature was used to return the characters to reality and prepare them to meet their moment of grace.

Although she is commonly related to the Southern Gothic writing style, she always insisted that this assessment was too narrow. She also rejected any requests to generalize her works by interviewers. Obviously, she wanted not just to entertain her audience, but also to educate it.

😷 Illness & Death

For more than a decade (since 1952), she suffered from lupus erythematosus, a genetic disease she inherited from her father. Most of these years were spent at Andalusia Farm in Georgia. Despite the illness, she wrote more than twenty short stories and two novels over this period.

She started her mornings attending Mass, then spent some hours writing, and in the afternoon, she recuperated and read.

O’Connor went to the Piedmont Hospital in Atlanta due to anemia in December 1963. She kept on writing there, as much as her health condition allowed.

Next July, she won the O. Henry Award for her story “Revelation.” Unfortunately, soon after this success, doctors found a tumor and removed it at Baldwin County Hospital. On August 3, 1964, Flannery O’Connor passed away because of renal failure. She managed to live seven years longer than the doctors expected.

In 1965, her last stories were published in the posthumous edition Everything That Rises Must Converge by Farrar, Straus and Giroux.