Literature Review

This chapter reviews what researchers have noted about the potential unfairness of the Chinese National College Entry Examination (NCEE). The investigation is informed by the need to inspect learning theories and educational practices adopted in different countries to comprehend how the Chinese education system compares internationally.

Guided by this goal, key sections of this chapter will explore what is known about the Chinese education system and how it compares to similar models internationally. However, before delving into this analysis, it is first important to understand the theoretical underpinning of college entry assessments.

Theoretical Review

Psychometric Theories

Psychometric theories have been used in different scientific fields to evaluate whether a test evaluates what it is intended to measure (Wolverton et al. 2018). Stated differently, they focus on the validity and reliability of test instruments. Psychometric tests emerge from a combination of different measurement instruments obtained from the fields of education and psychology (Wolverton et al. 2018).

For a long time, the principles of assessment derived from both disciplines have been used to undertake objective assessments of students’ skills, abilities and knowledge (Wolverton et al. 2018). Some researchers have extended the application of psychometric theories to investigating the validity of data collection instruments, such as questionnaires (Shirzadifard et al. 2018). Others have used the same approach to improve the measurement theory and their approaches have been instrumental in improving interclass correlation of research instruments (Loscalzo et al. 2019).

Psychometric theories refer to a broad group of concepts, such as the classic test and item response theories (Asempapa & Asempapa 2019). The Rasch model of measurement has also emerged from this area of research (Kliem et al. 2015; Maurer & Häfner 2014; Oranye 2016). Although they share similarities in the manner research variables are tested, they have distinct features relating to their origins and application (Chen & Chang 2018). Psychometric theories rely on factor analysis to understand the underlying dimensions of data. In addition, they use multidimensional scaling for evaluating student performance and data clustering to categorise different types of responses (Shirzadifard et al. 2018).

Broadly, psychometric theories emphasise the need to evaluate the reliability and validity of test instruments (Asempapa & Asempapa 2019). However, practitioners review these concerns within a broader assessment of test significance and effectiveness. Their focus is usually to understand whether the results that would be obtained from the tests are meaningful or arbitrary.

Learning Theories

Learning theories outline another set of concepts that have an impact on the evaluation of student test scores. They include four key attributes: behaviourism, cognitivism, constructivism and humanism (Bruijniks et al. 2019). These four tenets of learning theories underscore how tests are developed because most countries chose to use one technique, or a combination of multiple methods, to evaluate student performance (Shirzadifard et al. 2018).

For example, the constructivism approach has been adopted by countries that are interested in understanding how students construct meaning from different issues through knowledge development (Jung 2019). The main types of assessments that follow this model of examination are student-centred (Mensah 2015). Their main assumption is that “experience is the best teacher.” This approach to learning is commonly applied in many western countries because they do not focus on the reproduction of facts but rather the cognitive development and understanding of student performance (Walker & Shore 2015).

Therefore, in these kinds of learning settings, students are often provided with content-rich information that they would use to complete specific assessment exercises. They are also exposed to experience-based learning, which is often done through a review of several case studies for the learners to have a better understanding of educational concepts (Asempapa & Asempapa 2019). Broadly, there is a nexus between intended learning outcomes, assessment tasks and teaching, which supports the constructivist learning theory.

Cognitivism is another theory that has been used to inspire the development of learning assessment tools. It suggests that evaluations should be based on the processes for acquiring knowledge, as opposed to the observed behaviours that emerge from them (Villalobos & Dewhurst 2017). This view contradicts the evaluation approach undertaken by behaviourists because the latter focus on testing observed behaviour as opposed to the processes that created them in the first place (Abramson, Dawson & Stevens 2015). Therefore, cognitivism relies on an evaluation of the internal processes and connections that students have during learning to formulate assessment tests (Chen 2016).

Furthermore, this framework treats students as information processors because knowledge is presented as a schema or a symbolic measure of mental strength that needs to be assessed when the students are learning and not when the process is complete (Poletti et al. 2018). Therefore, examinations are done by measuring change in a learner’s schemata.

Based on the differences between cognitivists and behaviourist theories, some researchers have argued that each theory is a response to the other (Faretta-Stutenberg & Morgan-Short 2018). Particularly, cognitivism has been touted as a reaction to the widespread application of behaviourism in assessment scores. Nonetheless, the main objection that cognitivists have had towards behaviourists is the assumption that learning should be evaluated as a reaction to knowledge gain. Therefore, their main contention is the attempt by behaviourists to overlook the role of a student’s thinking processes when undertaking assessments (Mayes 2015).

The criticisms levelled against behaviourists were highlighted by language experts who argued that language proficiency cannot be achieved through conditioning (Tsushima 2015). For example, behaviourists have failed to explain how children can correctly pronounce certain words or make utterances in speech assessment about sounds that they have never been exposed to before (Ahmed et al. 2019). Therefore, cognitivists suggest that evaluations should be designed to assess a student’s inner abilities in learning. Their arguments have highlighted the role of the learner in student assessments because they are active participants in the process (Tsushima 2015).

Thus, the individualistic strategies adopted by various students should be considered as part of the evaluation because they determine how well they perform in their future educational endeavours.

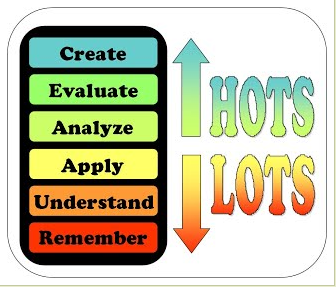

Lastly, Bloom’s taxonomy has been used to explain students’ learning processes by systematically highlighting the steps underpinning cognitive development (Yauhsiang 2019). Relative to this assertion, the model suggests that learning occurs in a hierarchical manner (Yauhsiang 2019). Therefore, sequentially, students have to start from lower order thinking, such as remembering important facts and transcend to higher-order thinking abilities, such as creativity. Figure 1 below highlights how the learning flow of this model.

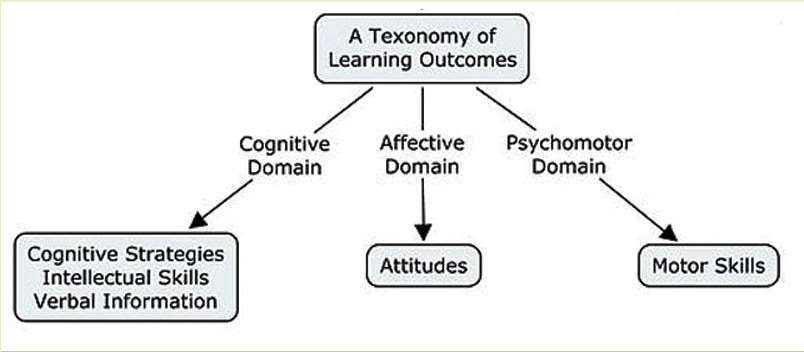

According to the diagram above, higher order thinking capabilities include creativity, evaluation and analysis. Comparatively, lower-order thinking includes remembering, understanding and applying knowledge. If these competencies are analysed according to their learning outcomes, they could be categorised into three domains namely: cognitive, psychomotor and affective (Yauhsiang 2019). The highest level of thinking is represented by the cognitive technique and it may include the integration of intelligence tests, verbal information and cognitive strategies.

The affective tenet of the model refers to an analysis of a student’s emotional needs, such as their feelings and reactions to different stimuli in the learning environment (Yauhsiang 2019). Lastly, the evaluation of psychomotor skills refers to a review of student’s physical abilities. As highlighted in figure 2 below, these competencies create the taxonomy of learning outcomes, which include an assessment of students’ attitudes, intellectual abilities and motor skills.

College Admission Tests around the World

It is important to understand how different countries design their college admission tests to have a broader understanding of conventional practices applied in this area of research. Some of the most commonly researched college admission tests are in the United States (US) and the United Kingdom (UK).

United States (US)

A paper done by International Student (2019) suggests that most admission tests done in the US require students to complete standardised tests for college admissions. However, there may be more than one test offered, depending on an institution and the course applied (Blume & Long 2014). The goal of formulating the standardised tests is to provide a common benchmark for evaluating the competencies of different groups of students who hail from varied education backgrounds (Black, Cortes & Lincove 2016).

International students are also commonly assessed based on whether they are able to speak in English or posses the necessary learning skills for completing the course tasks. Unlike most Asian countries, institutions of higher learning are given some independence in deciding the importance of test scores when making college admission decisions (Bastedo, Howard & Flaster 2016). Consequently, some institutions place a lot of emphasis on test scores, while others do not.

Colleges that rely on test scores to make admission decisions often subject students to additional tests, depending on the learning context and educational department involved (Bahr et al. 2019; Hout 2015). For example, international students are often subjected to an English proficiency tests (in addition to their test scores) as a prerequisite for making college admission decisions. Most colleges in the US often employ this strategy because the tests are designed for US-based students (Hurwitz et al. 2017).

The US college education system also recognises the need for different departments and institutions to undertake their local evaluation systems when making decisions regarding a student’s suitability to be admitted in specific courses (Hurwitz et al. 2015). Therefore, the level of skills or competencies required varies across different departments.

Most colleges in the US do not holistically examine test scores but go a step further to understand how each student performed on key subject clusters (Dakduk et al. 2016). For example, a student who has high scores in mathematics and fails to perform to the same standard in verbal tests could fail to be selected for an educational program located within an institution’s English department. Some colleges go a step further and analyse the results of proficiency tests to make admission decisions (Broda et al. 2018). For example, the English department could further analyse a student’s grammar, listening and reading skills to make an informed decision regarding whether they would be admitted to a program, or not.

United Kingdom (UK)

The college admission strategy used in the UK is dependent on the ability of students to prove that they can get good grades (Bowie 2019). Indeed, most universities require students to apply for placement based on their current achievement scores (Complete University Guide 2019).

They may also request students to state their predicted grades upon completion of their school leaving examinations. Similar to the US, the UK system also allows universities or colleges to undertake additional tests, especially in specialised schools or departments, such as law and medicine, to admit students (Bennett et al. 2017). Some UK universities also allow students to state any extracurricular activities they engage in as part of their college application processes. However, observers say it is unlikely that this information would sway their decisions (Sims, de Chenu & Williams 2014).

Like many Asian countries, the UK education system relies a lot on academic performance to make college admission decisions. However, unlike many Asian countries, the UK education system leaves some room for further interviews to be conducted before a final decision on placement is made (Sims, de Chenu & Williams 2014). The goal of scheduling these interviews is to assess the genuineness of the students and their real motive for choosing to study in select colleges (McLellan, Pettigrew & Sperlinger 2016). In other words, students are often tasked to demonstrate their enthusiasm for applying to be included in specific programmes.

Broadly, the main differentiating factor between UK universities and other national college admission systems is the multiplicity of education qualifications allowed. Notably, many UK universities consider applicants who have completed their A levels – A General Certificate of Education Advanced Level and have finished their secondary education or are looking for placement in a university. Most students who take these examinations are aged between 16 and 18 years (Bartram 2019).

Due to jurisdictional differences in the UK, some examinations are also considered unique to the locations. For example, students from Scotland could apply for placement in college using their Scottish (SQA) Higher Scores (Boliver 2016). These tests were originally introduced to promote independent learning and advance a nationalised outlook of test scores (Sims, de Chenu & Williams 2014). BTEC is another qualification accepted by UK universities for admission. However, it is mostly suitable to working professionals because of its strong focus on practical and applied learning (Sims, de Chenu & Williams 2014). Most students who gain entry into college using these scores are often allowed to proceed with their desired course from the second year.

The International General Certificate of Secondary Education (IGCSE) is another test that students could use to gain admission to a UK university. Notably, international students use it to study in the UK (Chankseliani 2018). However, not all forms of IGCSE are accepted by local universities. Therefore, students are often advised to check with their preferred universities to know whether their certifications are valid, or not. Broadly, these insights show that decisions relating to college admissions in the UK are multifaceted. Furthermore, a varied number of tests can be used to gain entry to a preferred university.

China

The Chinese National College Entry Examination (NCEE) is one of the most important tests for students who want to pursue higher education in the country (Wang 2019). In some quarters, this examination is also known as Gaokao (Wang 2019). It is often held annually (usually around June or July) and encompasses a population of about 9.6 million students (Steinfeld 2014). The tests are not restricted by age and students usually take them when they are in their last year of senior high school (Wang 2019). Depending on the administrative procedures adopted by each province in China, the NCEE usually takes about two or three days to complete. Students who take part in these tests are often required to select one area of examination, which is usually split between social and natural sciences (Wang 2019).

Social sciences often include an examination of students’ knowledge in specific subjects, notably: politics, geography and history. The natural sciences are administered in the same manner but they include a test of students’ knowledge on three key subjects: biology, physics and chemistry. Students are required to sit for these tests as a prerequisite for enrolling in most undergraduate programs, but exceptions could be made to those who have exceptional skills or pursue unique segments of education, such as adult education (Walker & Qian 2018). The overall mark awarded to every student who takes the NCEE is usually weighted against the subject areas identified above.

The administration of the NCEE varies across China (Ho, Sum & Wong 2018). Differences arise from the manner each province undertakes their examinations and how the tests are graded. However, the tests are administered uniformly from the provincial level and all subordinate administrative ranks. For example, each directly controlled municipality under the provincial administration implements the NCEE in a standard manner.

Nationally, the NCEE is administered at the same time because students sit for the examination in one session. In the last decade, there have been attempts to change the month of examination from July to June because of the challenges some students (especially in Southern China) experience with the extremes of weather (including flooding and extreme heat) (Zhao 2018). Traditionally, students were required to select a list of preferred subjects to study school (before sitting for the NCEE) but after receiving their test scores, they could amend their choices to reflect their performance (Ma 2015).

One issue affecting college admission processes in China is the existence of quotas. A discussion of these quotas is relevant to this study because it influences the probability of students who have completed the NCEE to secure college placement. Therefore, it is difficult to admit students into universities when specific quotas are already filled (Fu 2014). Each province has its own quota system. Their varied dynamics have long been the subject of debate because of their profound impact on the admission outcomes for students in selected universities (Fu 2014).

To understand how the admission quotas affect the NCEE and its administration, it is vital to understand that most top-tier universities in China are publicly funded. Therefore, the best universities in the country are publicly owned. For example, the Chinese government funded Fudan University to the tune of $326 million in 2011 (Fu 2014). If these findings were used as a template for other universities, it means that public funding could account for up to 44% of a university’s operational budget (Fu 2014).

The extent of government sponsorship affecting the operations of public universities in China means that they have a responsibility to fulfil the interests of the public (government) and not of individuals. In other words, they have a fiduciary responsibility of admitting local students, as an order of priority (Walker & Qian 2018). This privilege also means that the government has a stake in the formulation of admission quotas for each province. Usually, existing quotas are deemed arbitrary in nature but it is difficult to question the processes that led to their development, as the Chinese Ministry of Education does not provide an explanation for how they conduct their business (Fu 2014).

The development of the quota system stems from a centralised planning structure overseen by the Ministry of Education. Hansen (2015) says they are merely a way for provincial governments to compromise on their university admission criteria. Each year, Chinese universities publish their quota systems, thereby giving students who have received their NCEE scores an opportunity to evaluate their chances for admission and reapply accordingly (if need be) (Hansen 2015; Huang, Wang & Li 2015).

Some reports show that certain quota systems in China limit the opportunity for students to gain admission into specific programmes because of the low number of students who have secured placement in some provinces (Ho, Sum & Wong 2018). Relative to this finding, some institutions have been accused of not operating optimally because of this problem. This challenge influences how students enrol for specific courses, especially considering the difficulty of changing educational programmes midway through a semester (Ho, Sum & Wong 2018).

Broadly, the Chinese college application process is categorised into different levels, depending on the type of institution a student wished to study (Zhao 2018). For example, current application metrics are divided into vocational institutions, major universities, regular universities and early admissions. Each of these categories of admission may contain between four and six choices of study (Zhao 2018). The common practice is that students who are selected in each of the university applied for it as their first choice (Ho, Sum & Wong 2018).

However, it is common to find some cases where students have been allowed to apply for multiple institutions at different times and are selected to attend colleges, which were not their first choice. In some regions, such as Shanghai, students are allowed to apply for specific colleges and after learning of their NCEE scores, they could change their preferences and seek enrolment in other institutions (Ho, Sum & Wong 2018).

It is usually mandatory for students who take the NCEE to sit for three subjects: Mathematics, Chinese and a foreign language (Huang, Wang & Li 2015). English is the most common foreign language examined. However, other languages examined include Russian, German, French and Spanish (among others). From the early 2000s, integrated tests were also included in the NCEE (Ho, Sum & Wong 2018). They mostly involved sciences and humanities.

Although the importance of the integrated tests in admission review is still unclear, some Chinese institutions use associated test scores to make college admission decisions (Ho, Sum & Wong 2018). Some students are also required to sit for specific subjects, relative to the regional administrative regulations of the provinces involved (Mei, Brown & Teo 2018). However, to do so, they are required to abide by specific rules and regulations, such as respecting the laws of the country, must be holders of a high-school diploma or an equivalent and be in good health (Ho, Sum & Wong 2018). Existing laws and regulations also bar specific types of students from partaking in the exams.

The students include those who are currently studying higher education, have incomplete files (such as missing data on school history), and those who are serving a prison sentence or are facing prosecution for a specific crime (Mei, Brown & Teo 2018).

Students who are seeking to participate in specialised programs have to undergo additional screening. For example, some higher institutions of education, which want to enrol their students in art departments, may require prospective students to audition (Turner et al. 2018). Similarly, military education and police schools may require students to undergo a physical health examination or a political assessment test (Mei, Brown & Teo 2018). Lastly, some sports programs may require students to tryout specific exercises. The scores may be used to gain entry into other institutions of education outside of mainland China. For example, they could be used to secure admissions in higher institutions of learning in Hong Kong (Xu 2015).

Overall, the NCEE is deemed the only criterion for making enrolment decisions in China. Therefore, a poor performance in the test could be akin to giving up on the goal of studying in any of the country’s institutions of higher education. Based on its importance to the pursuit of education in China, studies have shown that the NCEE can have a significant impact on the lives of most teenagers and parents in the country (Mei, Brown & Teo 2018).

Japan

Although Japan is deemed one of the wealthiest countries in Asia, many students find it difficult to secure good spots in the country’s prestigious universities because of competition from other students (Coates 2015). Consequently, the national college entry examinations play a pivotal role in knowing who will be considered for admission and which group of students have to look for alternative educational opportunities.

In part, the Japanese college entry examination is deemed one of the most important tests in life because access to higher education is regarded as one of the most basic tools for getting a good job in the country (Sanders & Ishikura 2018). By extension, the social statuses of both Chinese and Japanese students largely depend on their ability to pass college entry examinations (Lai 2015).

The Japanese college entry examination strives to assess student’s understanding of basic academic knowledge. Introduced in 1990, the examination is designed as a multiple-choice test where students choose the right answer from a list of options (Sherlock 2016). Students are also known to sit for additional tests prepared by their desired universities as part of the selection process (Coates 2015). However, before undertaking these examinations, the students must first meet the minimum threshold of performance (set by the national examinations) (Uzama & Walter 2018). Those that fail to meet this criterion are often barred from taking the institutional tests (Yamada 2018). Nonetheless, broadly, the decision of universities to admit a student depends on a review of both institutional and national tests.

Summary

This chapter has shown that different countries have their unique college entry examinations based on their local educational policies and student dynamics. However, no concrete research has been undertaken to evaluate the merits or demerits of one college entry examination with another, especially in terms of fairness. Furthermore, current studies have failed to compare two or more educational systems with each other to understand their fairness.

The findings of this review also suggest that there is a commonly agreed understanding that, although the concept of fair grading is straightforward, guaranteeing fairness in examination is a problematic issue. This study seeks to fill this research gap by investigating the unfairness of the Chinese NCEE vis-a-vis the Japanese college entry examination. The approaches and strategies that will be adopted to achieve this objective are described in the methodology chapter below.

Methodology

This chapter highlights the techniques used by the researcher to undertake the study. Its key sections highlight the research approach, design, data collection method and data analysis techniques used by the researcher to carry out the investigation. At the end of the chapter, the ethical considerations underpinning the study are explained.

Research Approach

Schwemmer and Wieczorek (2019) say there are two main approaches to research: qualitative and quantitative. The qualitative method is focused on the collection of subjective research variables, while the quantitative method is linked to the collection of measurable data (Claasen et al. 2015; Dobbie, Reith & McConville 2018). This study involved a combination of both techniques within a wider mixed methods research framework. Archibald et al. (2015), Walker and Baxter (2019) say the mixed method research approach involves the integration of both qualitative and quantitative assessments methods within one study framework. The main motivation for using this technique is to obtain a complete and synergistic understanding of the research topic. Stated differently, the mixed methods approach was pivotal in obtaining holistic information about the research issues (Snelson 2016).

The use of either of the two methods (qualitative or quantitative) in isolation may have led to the omission of relevant data simply because they failed to meet the analytical framework. For example, it would not be possible to integrate statistics in the research findings if the qualitative approach was used in isolation (Flemming et al. 2016). Therefore, the integration of both techniques (qualitative and quantitative) provided a comprehensive outlook of the research findings. In addition, the use of both techniques helped to compare different sets of data with each other. For example, the qualitative information was used to explain quantitative data. Similarly, quantitative information was used to review the qualitative data.

Research Design

According to Research Rundown (2019), there are six main research designs linked to the mixed methods approach. They include sequential explanatory, sequential exploratory, sequential transformative, concurrent triangulation, concurrent nested and concurrent transformative techniques. Each method was assessed for its merits and demerits as well as appropriateness for the study and the findings are highlighted below.

Sequential Explanatory

The sequential explanatory method gives preference to the collection of quantitative data (Fetters & Freshwater 2015; David et al. 2018). Later, qualitative information is obtained and data analysis commences thereafter. Since qualitative data is collected last, it is used to explain the findings of the quantitative information (Uprichard & Dawney 2019).

Sequential Exploratory

The sequential exploratory technique is the opposite of the sequential explanatory method because it gives priority to the collection of qualitative data (Research Rundown 2019). Therefore, quantitative information is used to explain qualitative findings. Researchers who are developing or testing a new instrument have used this technique with great success (Nzabonimpa 2018). Besides, they have expanded its use to explore new phenomena (Research Rundown 2019).

Sequential Transformative

The sequential transformative technique merges the characteristics of the sequential explanatory and exploratory techniques because it does not give preference to the collection of one type of data (Research Rundown 2019). Instead, both qualitative and quantitative information can be collected at the same time and the results integrated at a later stage of data analysis (Dewasiri, Weerakoon & Azeez 2018).

Concurrent Triangulation

The concurrent triangulation technique relies on the use of both sets of data (qualitative and quantitative) to corroborate findings (Mertens 2015). In other words, data collection occurs concurrently. This approach allows a researcher to use the strengths of one type of data collection to overcome the weaknesses of another (Moseholm & Fetters 2017).

Concurrent Transformative

The concurrent transformative method relies on the use of one theory to dictate how data collection will happen in a study (Research Rundown 2019). Therefore, the infusion of qualitative or quantitative data is aimed at analysing the research issue at multiple levels (Johnson, Murphy & Griffiths 2019).

Concurrent Nested

The concurrent nested technique supports the use of one type of data (either qualitative or quantitative) as the main method of data collection, while the other becomes embedded on the project (Poth & Onwuegbuzie 2015). Researchers who use this type of technique often want to analyse an issue across multiple levels of assessment or to use the secondary method to address a different question other than the main one (Puigvert et al. 2019).

Based on its characteristics, the concurrent nested technique was selected as the appropriate design for this study. The justification for its use is informed by the fact that quantitative data was only used as an appendage of the main research method (qualitative). The focus on qualitative data was informed by the emphasis on fairness as a key research variable. This concept is inherently a subjective issue and can only be analysed qualitatively. Thus, quantitative data was obtained to support the findings.

Data Collection

Secondary data was used to come up with the research findings. Stated differently, published research materials were reviewed and evaluated for relevance. The research was conducted online by retrieving articles from three different databases (Sage journals, Google Scholar and Jstor). The keywords and phrases used were China, Japan, and National College Entry Examinations. Hundreds of articles were obtained from the search.

They were further assessed according to their publication dates to remain with articles that were written in the last five years (2014-2019). The main goal of using this strategy was to obtain the most relevant information because older articles may contain outdated data. Upon reviewing the available articles using this search criterion, 149 articles were left for more analysis. The materials were subjected to an interdisciplinary analysis where emphasis was made to only include articles that were published in peer-reviewed journals. In the end, 91 articles were left for review.

The secondary research approach was used because of the sheer scope of the investigations. In other words, the study issue was of a national scale and it was not possible for the researcher to carry out a primary investigation of the same magnitude. Furthermore, the secondary data collection method was convenient for the researcher to use considering the resource and time limitations attributed to the university’s programme calendar. Therefore, it was possible to obtain a wealth of information within a short time.

Secondary research was the preferred method of data collection because the findings of this study are indicative. In other words, the information provided in this document only appear as a starting point for conducting future studies about the research investigation. Therefore, through this analytical method, it was easy to have a proper understanding of what has already been done and said about the merits and demerits of the NCEE as well as finding out whether other comparative analyses for the Chinese and Japanese college entry examinations have been conducted. The information collected from the secondary information would also help to plan future primary investigations because it is easy to identify key research gaps that could be filled with a primary investigation (Zhang, Albrecht & Scott 2018).

Data Analysis

Data was analysed using the thematic and coding method. This technique was applied by identifying recurring patterns of findings that helped to answer the research questions. These patterns were later grouped together to create the themes and subthemes used to develop the codes for analysis. Nonetheless, the process involved six key steps as outlined below.

Step 1 (Familiarising with the Data)

The first step of data analysis involved a familiarisation with data. In other words, the information contained in the research articles were quickly perused and important points noted on a separate piece of paper, as recommended by Armborst (2017) for reference purposes. The process also involved analysing the data actively and developing meaning out of them. Information was read and reviewed to understand the contents of each research article. The findings obtained from this process were instrumental in completing the second phase of analysis – generating initial codes.

Step 2 (Generating Initial Codes)

Codes were developed to identify similar patterns in the texts reviewed. The process was systematic and involved an organisation of the research information based on how they helped to address the research issue. The process was cyclic because information was analysed and reanalysed to understand how they fit within the research topic. Furthermore, as proposed by Lewinski et al. (2019), information was consistently reviewed across different analytical phases until a strong theme emerged. The process of generating initial codes also involved understanding the subjective meanings of the information collected to make sense of their importance to the investigation.

The process took several weeks to complete because several codes were entered, eliminated and adjusted to fit specific analytical frameworks. The codes were later used to collect pieces of data when carrying out the final analysis., For example, all the pieces of information relating to the Chinese college entry examination were grouped under one code and data relating to the Japanese education system assigned a different code. The digits generated helped to set the stage for further analysis by organising ideas that emerged from the literature review. Attention was made to analyse each data item to avoid the possibility of missing unidentified patterns.

Step 3 (Searching For Themes)

The process of searching for themes was undertaken with the goal of analysing potential codes and evaluating how they help to address the research issue. The codes generated from previous data analysis processes were combined to understand how they create broader patterns in the data to form links for different codes. These links were also analysed to understand how they fit within different levels of existing themes. The themes were different from the codes because they outlined meanings or phrases that were used to address the research issue.

Step 4 (Reviewing the Themes)

The fourth step of data analysis involved a review of the themes generated above. The exercise involved assessing how the information obtained fit within the overall data and scope of research. At this stage of data analysis, some themes blended with each other while others were separated to form a broader schema of findings. Two main processes were adopted to facilitate this process: identifying connections between overlapping themes and identifying deviations from the coded data. Broadly, the codes helped to link desired data with the perceived meaning.

Step 5 (Defining and Naming Themes)

The process of defining and naming themes aided in analysing information contained in each schema (Ando, Cousins & Young 2014). The data analysis process here was geared towards identifying how each theme helped to create the “bigger picture” of the findings. Emphasis was on understanding how each aspect of data helped to address the research questions and why they were interesting enough to be included in the final report. Therefore, this data analysis process helped to understand how the themes fit within the wider picture of investigation as well as how they stand independently as autonomous themes (Hilton & Azzam 2019).

Step 6 (Producing the Final Report)

The process of producing the final report was undertaken after reviewing all the themes identified above. As recommended by Nowell et al. (2017), emphasis was made to only include data segments that helped in addressing the research topic. Therefore, the thematic analysis was developed in a manner that represented the complexity of the investigation and its linked data.

Ethical Considerations

As highlighted in this chapter, this paper is a secondary review research materials that have explored the unfairness of the Chinese NCEE, vis-a-vis the Japanese system. Typically, secondary research investigations do not attract the same ethical rigour as primary research studies do because of the lack of human subjects as the main source of data (Ando, Cousins & Young 2014). However, with the advent of technology, researchers have emphasised the need for an ethical review of the processes followed when obtaining research data in secondary investigations (Hilton & Azzam 2019).

Relative to this concern, all the information obtained from other studies were correctly cited and credit given to the respective authors. All the materials sourced for review were also publicly available and no special permissions were required to access them.

Findings

This chapter highlights the main findings obtained from the implementation of the research strategies highlighted in chapter three above. It also highlights key findings associated with the research questions. As demonstrated in chapter three above, materials for the secondary analysis were obtained from reputable online databases (Sage journals, Google Scholar and Jstor). The keywords used were China, Japan and National College Entry Examinations.

Hundreds of articles were generated but they were further subjected to a more rigorous review, which analysed their publication dates and relevance to the topic. The main goal of undertaking additional scrutiny was to obtain the most relevant information from the research materials because older articles may contain outdated data. Upon reviewing the available articles using this search criterion, 149 articles remained for further analysis. The section below highlights the main themes that emerged from the analysis.

Themes

Administration and interpretation of test scores were the two major themes that emerged from the investigation. Notably, they underpinned the basis for a review of biasness and unfairness of the NCEE. Furthermore, they were the two major comparative platforms for evaluating the Chinese and Japanese college entry examinations. The themes are further discussed below.

Administration of College Examinations

A comprehensive review of multiple research articles revealed that one of the main reasons why some observers consider NCEE unfair is its independent proposition of testing procedures (Sanders & Ishikura 2018). This concept means that different provinces in China can administer the examination whichever way they wish. This independence in test administration means that there will be differences in education resources among these jurisdictions. They will either impede or enable students to learn or pass their tests. For example, differences in experienced proposition experts and management personnel across varied regions contribute to variations in education outcomes (Sanders & Ishikura 2018; Mei, Brown & Teo 2018).

Relative to the above challenge, some provincial governments have had to increase their budget allocations to offset some of the credibility issues associated with NCEE. Others have made repetitive investments in human resources and finances to fill in the gaps created by differences in social and economic development across varied regions. This challenge is compounded by the fact that social and economic differences among different provinces and regions in China have resulted in disparities in educational outcomes. Therefore, it is unfair to subject students who have different capabilities for success to the same examination standards.

Interpretation of Test Scores

Some of the studies sampled in this review suggested that most Chinese universities emphasis on test scores at the expense of other metrics of assessment, such as nurturing talents. For example, in a document authored by Bingqi (2016), it was reported that the top two universities in China admitted top scorers of the NCEE examination on the night that the scores were announced. This admission criteria and the expediency that the institutions demonstrated in granting admission show that there is an overemphasis on test scores, as opposed to other metrics of assessment. Some quarters of the Chinese society have noticed this problem and petitioned authorities to restrain the examination council from publishing results (Bingqi 2016).

Other top universities around the world often rely on other metrics (besides test scores) to admit students in universities. However, Chinese universities adopt a simplistic approach to selecting students because of the over reliance on NCEE scores. Therefore, they do not have plans to conduct follow-up interviews to assess other areas of competence that students may or may not have, and which would be instrumental in informing their admission decisions. Bingqi (2016) affirms this problem and wonders why changes have not been made to the system even after the reform of college admission rules. This challenge is partly responsible for the disconnect that exists between the enrolment procedures of several universities and the cultivation of talent in these universities.

Employers have also voiced concerns regarding the inability of new graduates to perform as desired in their respective work posts (Bingqi 2016). The competition between major universities in China to attract the best performing students also shows that they are not keen on cultivating talent. Again, this problem traces its roots to the NCEE because of its unified talent evaluation metric (Walker & Qian 2018).

Therefore, it lacks a multiple talent evaluation system because of its overreliance on test scores. Consequently, there is little regard for independent college admission norms. Furthermore, current reforms on college admission criteria still rely on the NCEE, which means that they still use test scores to make admission decisions (Walker & Qian 2018).

Current college admission reforms have improved the rights of colleges to enrol students in their institutions but the choices students have in selecting a university of their choice is still limited (mostly by test scores). This problem is partly highlighted by an analysis of Tsinghua and Peking universities, which still base their performance on the number of top scorers they have (Bingqi 2016). In turn, this strategy fuels the unhealthy competition witnessed among top universities to secure enrolment of students with the highest scores.

Some reports show that some of the major universities around the world have detected the problem with the Chinese education system and reduced their yearly quotas for the same group of students after realising that some of the top students lack creativity (Bingqi 2016). This problem comes from the NCEE because of its simplistic nature. Therefore, students who have high ranking in terms of other performance indices (besides test scores) are easily overlooked (Walker & Qian 2018). Consequently, the only students who benefit from it are those who memorise facts and reproduce them for purposes of passing the examination.

Summary

As highlighted in this chapter, the two major themes underpinning the research investigation were administration and interpretation of test scores. The NCEE also emerged as having a very simplistic view of assessment because of its excessive focus on test scores. The unfairness of this system is further tested in chapter five below through a comparison of its merits with the Japanese model.

Discussion and Analysis

This chapter reviews the findings highlighted in chapter 4 above. Key sections of this chapter will show how the NCEE is unfair to specific groups of students and why there is a need to redesign it. However, before delving into these details of analysis, it is first important to understand similarities and differences between both college examination systems.

Similarities of the Japanese and Chinese College Entry Examinations

Understanding the differences and similarities between the Chinese and Japanese college entry examinations was a key part of this analysis. It emerged that both entry examinations are similar in terms of the attention they generate and their intended purpose. For example, both examinations are widely popular in their respective countries and garner widespread attention when the results are announced (Papay, Murnane & Willett 2015). Furthermore, they are both administered within the same duration (between two to three days) and serve a similar purpose of evaluating students’ competencies for admission into college (Papay, Murnane & Willett 2015).

The limited admission spots available in Japanese and Chinese universities explain why both systems are under intense scrutiny because students have to be evaluated using competitive college admission examinations to gain entry to top universities. However, the Japanese national examination system is better organised and implemented compared to the Chinese one because of its central organisation structure.

For example, a review of the NCEE’s administrative structure reveals significant differences with the Japanese model because the NCEE is not centrally organised, while the Japanese one is overseen by one entity – Independent Administrative Institution (IAI) (Sanders & Ishikura 2018). A review of the evidence also showed that the Chinese NCEE lacks a central organisation structure because provincial authorities wield a lot of power in their administration (Ho, Sum & Wong 2018). Therefore, there could be variations in how authorities administer the examinations. These differences influence the interpretation of test scores.

One key finding that emerged from this investigation is the difference sin admission scores generated by the NCEE. This system makes it difficult to equitably assess a student’s competencies and suitability for university education because of the lack of a standardised administrative structure. This model promotes a kind of rote learning, which is prevalent throughout China (Ho, Sum & Wong 2018). It makes it easy to question the true purpose of the NCEE because it curtails creativity and fuels an obsession with test scores.

Differences of the Japanese and Chinese College Entry Examinations

Another notable difference between the Japanese and Chinese examination systems is the overreliance on test scores. Notably, the Chinese NCEE lays a lot of emphasis on test scores but the Japanese examination system does not have such characteristics. Instead, independent educational institutions have assumed additional responsibilities of conducting further assessments to make admission decisions (Coates 2015). Comparatively, students in China may receive admission approvals on the same day the NCEE tests scores are published. Therefore, they are unwilling to undertake additional tests to assess a student’s competencies.

This decision-making approach means that the NCEE is weaker compared to the Japanese college entrance examination because of its lack of rigour. If left unchecked, it may cause long-term problems in developing a motivated student body. Furthermore, it may explain why the Chinese NCEE is unfair because the reliance on test scores, as the only consideration for admission, ignores other non-standardised competencies that may be important in the determination of a student’s competence.

Weaknesses of the Chinese NCEE

Broadly, the findings highlighted in this study draw attention to differences in administration and interpretation of test scores, as the two key areas of NCEE operation, which create unfairness in formulating college admission decisions. Administrative differences stem from the failure to develop standardised evaluation processes across different provinces and the inability to account for the effects of socioeconomic differences across different jurisdictions, which could affect education access.

For example, the effects of socioeconomic factors on education access for students who sat their examinations in Shanghai and rural areas of China promotes unfairness because they limit access to colleges for students who sat for the NCEE in rural areas. Therefore, despite having many universities, Shanghai admits many local students at the expense of “foreign” ones, even though they may score significantly lower marks on the NCEE, as their peers who do not come from the province.

Granted, although the Chinese NCEE is regarded as a standardised test, there is little evidence to suggest that it actually meets this profile. As stated above, its challenges stem from the differences in examination implementation processes across different provinces. Consequently, there is no centralised organisational structure that governs how they are administered. Thus, differences in how to interpret test scores arise.

Another critical issue that has emerged from this study is the consistent emphasis on test scores in the Chinese education system. This bias means that the NCEE is not a holistic assessment framework because it does not account for other merits, such as creativity, that a student may have and which are instrumental in making college admission decisions. Therefore, it is difficult to understand how an education system that is supposed to nurture talent focuses only on the quantitative aspects of student competence and fails to account for the subjective attributes that test scores do not capture.

The above concern is particularly important in evaluating how students who are selected to study “subjective” courses, such as the arts, are admitted to specific educational programs because the system fails to account for the unquantifiable merits needed in selecting the right candidates. It is no wonder that poor results have been reported after students secure admission in respective colleges (Sanders & Ishikura 2018).

For example, evidence has been provided of how some Chinese students studying abroad fail to perform as desired, despite having high scores on their NCEE (Sanders & Ishikura 2018). This issue has been linked to the reduction in admission quotas for Asian students in some western countries.

A keener look at the Chinese NCEE shows that the system favours students from wealthy families and cities. Although the examination system was introduced to promote equality, it is discriminatory because students who come from rural or poor families fail to get the same placement opportunities as those who hail from cities or come from wealthy families. For example, students who come from Beijing and have a household registration from the same area perform better on the NCEE and get better placements compared to those who hail from different parts of China (Wang 2019).

Beijing students are the biggest beneficiaries of NCEE’s weaknesses because they often attain a higher score than their peers from other regions (Wang 2019). Differences in admission scores only outline part of the problem because universities also have varied admission criteria, which further complicate the evaluation process. The presence of different results analysis methods means that a student who scores highly on the NCEE may miss an opportunity to be admitted to a course of their choice because they did not meet the test scores put in that university.

The biasness that exists in the Chinese college entry examinations towards the poor and rural people is not a new phenomenon because it has also been observed in other countries where the rich have an added advantage in securing the best college placements. The problem is notably common in America where several news reports have shown that students from wealthy families are significantly favoured when making college admissions, relative to the general student population. This problem is commonly observed as a review of selection processes for elite schools. The challenges that America has experienced in changing this situation can be compared with China because studies have shown that the system is inherently flawed to favour students from wealthy families even if changes are not made to it.

Unfairness in the System

The administration of the NCEE is also inherently unfair because it requires students to go back to their provinces of original residences to take the examination. This challenge curtails their prospects to score highly on these examinations and secure a place in a good university because it forces them to familiarise themselves with new materials when they change residence (Fu 2014). Furthermore, they have to face fiercer competition when moving provinces because of the social and economic differences across these provinces, which affects the educational outcomes of the students involved.

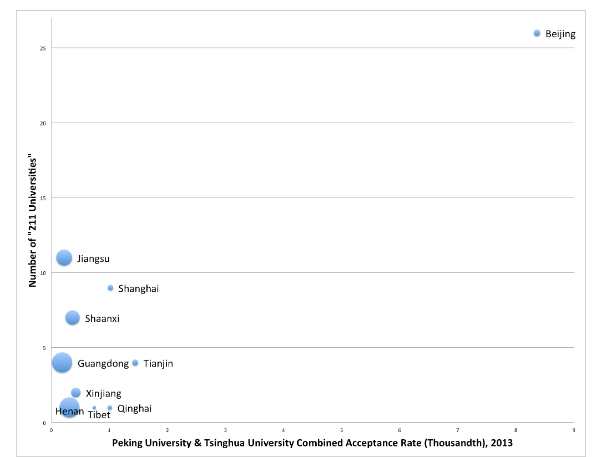

Therefore, a learner who performs well in an underserved province may have diminished chances of securing a place in college if they sit for the NCEE in another province, which has high-performing students (Fu 2014). The regional differences across multiple jurisdictions that affect student test scores and admission rates are partly affirmed by research studies that show biases in recruitment across different cities and jurisdictions. For example, according to figure 1 below, although students from Beijing are fewer than other cities and provinces in China, they secure the highest rates of enrolment in major universities.

The willingness of major colleges to accept students from Beijing, relative to other cities and provinces, is ironic because students from big cities in China do not compete for top universities as much as those from rural areas do (Fu 2014). This discrepancy emerges from the fact that major universities in Beijing often reserve many spots for students who come from the province. Therefore, it is possible to find that they have lower admission test scores compared to students from other provinces. This system is unfair to students who come from rural locations because, despite having fewer educational resources, they are forced to attain high test-scores to gain entry to top universities.

A deeper analysis of the enrolment processes of the two top universities in China mentioned above (Peking University and Tsinghua University) reveals the biases that exist in the enrolment process, subject to NCEE test scores. It is estimated that the two institutions will admit about 84 students out of a possible 10,000 that sought admission, while only two out of a possible 10,000 students who took part in the same examination in Gunagdong will be considered for admission (Fu 2014).

Underpinning the above statistics is the role of social and economic inequality in influencing admission criteria (Papay, Murnane & Willett 2015). Notably, wealthy families in China often move to Beijing and Shanghai before taking the NCEE examinations to improve their odds of gaining access to good universities (Fu 2014).

Based on the findings highlighted in this study, rich students from these cities and provinces tend to get higher chances of being enrolled in good universities compared to middle class and low-income students who have to “fight it out” with other students for enrolment in prestigious universities. Nonetheless, native students in Beijing, Shanghai and other major cities in China have started to advocate for the protection of their education rights because they are opposed to the “migration” of wealthy students from other provinces that come to sit for the NCEE in their provinces (Fu 2014).

This social discomfort brought by the administration of the examination shows that it is inherently unfair to lower and middle income students who have to work harder to secure valuable slots in prestigious universities. Comparatively, the rich are exploiting systemic weaknesses to improve the odds of their children being admitted in prestigious universities by using their money and status as leverage.

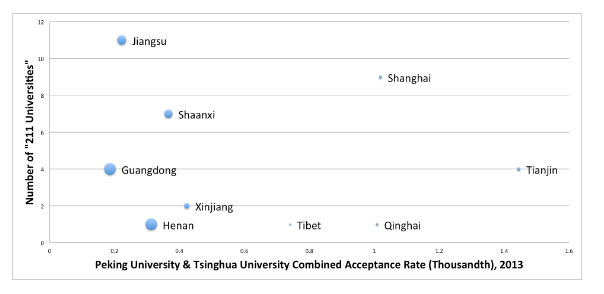

Competition for top university positions also fuel the unfairness of the NCEE system because studies have shown the difficulty of entering specific universities because of high competition and few positions available. For example, students who take examinations in certain parts of China, such as Jiangsu, have a more difficult time gaining access to top universities compared to their peers from other regions because these localities have many high performing high schools (Fu 2014). This is why it is estimated that in a student population of about 10,000 people who took the NCEE in Jiangsu only two would be considered for enrolment in top universities (Fu 2014). Figure 2 below shows the distribution in the number of universities and the combined acceptance rate of students form Peking and Tsinguah universities.

According to the graph above, students who sat the NCEE at Jiangsu tend to be accepted by Peking and Tsinguah universities at lower rates than those who sat for the same examination at Henan. In other words, the test scores for students who were admitted at Jiangsu are significantly lower than the scores for those from Henan. This admission criterion exists despite the fact that Jiangsu has more universities than Henan.

Lastly, the NCEE is also unfair to some students because of existing legal clauses demanding the preferential treatment of some students. Indeed, certain segments of the Chinese population, such as the disabled, receive preferential treatment when it comes to the NCEE scoring metric because they are easily given higher grades compared to other students (Fu 2014). This system adds to the complexity of the NCEE

Areas that Need Attention

Based on the insights highlighted above, one of the major differences observed between the Chinese and Japanese education systems is the lack of assessment rigour on the part of the Chinese. There is a need to rethink the importance of formulating additional tests to assess a student’s suitability for selected courses and educational programs, or not. Stated differently, the overreliance on test scores should be reviewed with the hope of creating a comprehensive framework for making college admission decisions. The potential for making these adjustments lies in the improvement of equity in the admission process because some students have “other” skills that should not be discounted when making admission decisions.

Since it has been established that the NCEE fails to capture non-academic competencies because of the overreliance on test scores, there is a need to re-examine whether lessons could be borrowed from the Japanese system because the latter is more comprehensive in the manner students’ competencies are reviewed. Indeed, most top universities in Japan undertake additional tests (besides the national examination) to evaluate a student’s competencies in learning.

This strategy means that even though a student may score highly on the national examination, they may still miss the opportunity to secure a spot in selected universities based on their performance on additional tests. In China, admission is almost automatic when a student posts high scores (Zhao & Yang 2019).

Based on the above-mentioned observations, there is a need to rethink whether it would be prudent to overhaul the NCEE to reflect other non-academic qualities, such as communication skills and logical thinking, when conducting tests. This strategy could influence the nature of the examination because it could become more holistic and acceptable to all students (Wang 2019; Yuan & Li 2019). To ease the pressure that most students experience before taking the NCEE, it is prudent to look at the NCEE’s structure and find out whether it would be prudent to substitute the standardised test model for a learning achievement framework, which should be administered throughout a student’s learning experience.

This area of analysis is closely linked with the views of Latifi et al. (2016), which suggest that such a system change means a departure from the one-off assessment model where students are examined in one sitting. Such a model is linked with increased anxiety levels for students because of the impactful nature of the tests on their education and careers (Wang, Liu & Zhang 2018). For example, a student who is unwell during the examination period may fail to gain entry into a college of their choice because the test was administered when they were sick.

However, if this system were overhauled and substituted with a long-term learning achievement test, their learning competencies could more effectively studied. The assessments done could also be more informed and comprehensive, thereby presenting the true picture of their academic competencies (Yuan 2018). Furthermore, the narrow focus that Chinese universities and admission boards have placed on dismal score differences could be looked at because slight differences in test scores are not a reliable measure of academic ability (Cui, Lei & Zhou 2018: Hao et al. 2019).

The above-mentioned views highlight the need to examine whether it would be prudent to introduce continuous assessments in China. Potentially, students will not only be assed in one event but through a combination of several others. An unintended positive effect that may emerge from the adoption of this strategy is the heightened level of preparedness for the students to sit for exams because they will always be looking forward to completing periodic tests.

Given the importance of the NCEE to a student’s academic life and career prospects, such biases should not exist because they have far-reaching implications on the self-esteem and societal standing of students who are often under immense pressure from family members to perform well (Zhang 2019). Therefore, the current setup of the NCEE fails to account for the cultural attributes or competencies of a student, and there is a need to examine how this system can be remodelled for better outcomes. Indeed, it fails to effectively evaluate the suitability of students to respective college programs.

Summary

There is little contention regarding the need to make examinations fair to all students. However, there is no commonly agreed measure for determining fairness. In other words, it is a subjective concept. The findings of this study suggest that there is a commonly agreed understanding that, although the concept of fair grading is straightforward, guaranteeing fairness in examination is a problematic issue.

The paradox of this assessment is that even though fairness could be interpreted to mean the application of one rule for all students, such a strategy would only magnify the implications of pre-existing prejudices and unfairness that already exist in the system in the first place. Furthermore, the mere application of common rules in examination fails to account for diversity in student talents. Consequently, there is a need to examine the concept of fairness in formulating assessments.

Reference List

Abramson, J, Dawson, M & Stevens, J 2015, ‘An examination of the prior use of e-learning within an extended technology acceptance model and the factors that influence the behavioral intention of users to use m-learning’, SAGE Open, vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 1-10.

Ahmed, A, Wojcik, EM, Ananthanarayanan, V, Mulder, L & Mirza, KM 2019, ‘Learning styles in pathology: a comparative analysis and implications for learner-centered education’, Academic Pathology, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 1-10.

Ando, H, Cousins, R & Young, C 2014, ‘Achieving saturation in thematic analysis: development and refinement of a codebook’, Comprehensive Psychology, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 1-10.

Archibald, MM, Radil, AI, Zhang, X & Hanson, WE 2015, ‘Current mixed methods practices in qualitative research: a content analysis of leading journals’, International Journal of Qualitative Methods, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 5-33.

Armborst, A 2017, ‘Thematic proximity in content analysis’, SAGE Open, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 1-10.

Asempapa, B & Asempapa, RS 2019, ‘Development and initial psychometric properties of the integrated care competency scale for counselors’, SAGE Open, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 1-10.

Bahr, PR, Fagioli, LP, Hetts, J, Hayward, C, Willett, T, Lamoree, D & Baker, RB 2019, ‘Improving placement accuracy in California’s community colleges using multiple measures of high school achievement’, Community College Review, vol. 47, no. 2, pp. 178-211.

Bartram, D 2019, ‘The UK citizenship process: political integration or marginalization?’, Sociology, vol. 53, no. 4, pp. 671-688.

Bastedo, MN, Howard, JE & Flaster, A 2016, ‘Holistic admissions after affirmative action: does “maximizing” the high school curriculum matter?’, Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, vol. 38, no. 2, pp. 389-409.

Bennett, K, Cochrane, A, Mohan, G & Neal, S 2017, ‘Negotiating the educational spaces of urban multiculture: skills, competencies and college life’, Urban Studies, vol. 54, no. 10, pp. 2305-2321.

Bingqi, X 2016, Gaokao reveals unhealthy college contest. Web.

Black, SE, Cortes, KE & Lincove, JA 2016, ‘Efficacy versus equity: what happens when states tinker with college admissions in a race-blind era?’, Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, vol. 38, no. 2, pp. 336-363.

Blume, GH & Long, M 2014, ‘Changes in levels of affirmative action in college admissions in response to statewide bans and judicial rulings’, Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, vol. 36, no. 2, pp. 228-252.

Boliver, V 2016, ‘Exploring ethnic inequalities in admission to Russell Group universities’, Sociology, vol. 50, no. 2, pp. 247-266.

Bowie, RA 2019, ‘Christian universities and schools in relation and context’, International Journal of Christianity & Education, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 1-10.

Broda, M, Ekholm, E, Schneider, B & Hutton, AC 2018, ‘Teachers’ social networks, college-going practices, and the diffusion of a school-based reform initiative’, SAGE Open, vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 1-10.

Bruijniks, SJ, DeRubeis, RJ, Hollon, SD & Huibers, M 2019, ‘The potential role of learning capacity in cognitive behavior therapy for depression: a systematic review of the evidence and future directions for improving therapeutic learning’, Clinical Psychological Science, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 668-692.

Chankseliani, M 2018, ‘Four rationales of the internationalization: perspectives of U.K. universities on attracting students from former Soviet countries’, Journal of Studies in International Education, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 53-70.

Chen, R 2016, ‘Learner perspectives of online problem-based learning and applications from cognitive load theory’, Psychology Learning & Teaching, vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 195-203.

Chen, Y & Chang, HH 2018, ‘Psychometrics help learning: from assessment to learning’, Applied Psychological Measurement, vol. 42, no. 1, pp. 3-4.

Claasen, N, Covic, NM, Idsardi, EF, Sandham, LA, Gildenhuys, A & Lemke, S 2015, ‘Applying a transdisciplinary mixed methods research design to explore sustainable diets in rural South Africa’, International Journal of Qualitative Methods, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 69-91.

Coates, J 2015, ‘Unseeing” Chinese students in Japan: understanding educationally channelled migrant experiences’, Journal of Current Chinese Affairs, vol. 44, no. 3, pp. 125-154.

Complete University Guide 2019, University admissions tests and qualifications. Web.

Cui, Y, Lei, H & Zhou, W 2018, ‘Changes in school curriculum administration in China’, ECNU Review of Education, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 34-57.

Dakduk, S, Malavé, J, Torres, CC, Montesinos, H & Michelena, L 2016, ‘Admission criteria for MBA programs: a review’, SAGE Open. vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 1-10.

David, SL, Hitchcock, JH, Ragan, B, Brooks, G & Starkey, C 2018, ‘Mixing interviews and Rasch modeling: demonstrating a procedure used to develop an instrument that measures trust’, Journal of Mixed Methods Research, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 75-94.

Dewasiri, NJ, Weerakoon, Y & Azeez, AA 2018, ‘Mixed methods in finance research: the rationale and research designs’, International Journal of Qualitative Methods, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 1-10.

Dobbie, F, Reith, G & McConville, S 2018, ‘Utilising social network research in the qualitative exploration of gamblers’ social relationships’, Qualitative Research, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 207-223.

Faretta-Stutenberg, M & Morgan-Short, K 2018, ‘The interplay of individual differences and context of learning in behavioral and neurocognitive second language development’, Second Language Research, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 67-101.

Fetters, MD & Freshwater, D 2015, ‘Publishing a methodological mixed methods research article’, Journal of Mixed Methods Research, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 203-213.

Flemming, K, Closs, SJ, Hughes, ND & Bennett, MI 2016, ‘Using qualitative research to overcome the shortcomings of systematic reviews when designing of a self-management intervention for advanced cancer pain’, International Journal of Qualitative Methods, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 1-10.

Fu, Y 2014, China’s unfair college admission system. Web.

Hansen, AS 2015, ‘The temporal experience of Chinese students abroad and the present human condition’, Journal of Current Chinese Affairs, vol. 44, no. 3, pp. 49-77.

Hao, Y, Liu, S, Jiesisibieke, ZL & Xu, YJ 2019, ‘What determines university students’ online consumer credit? Evidence from China’, SAGE Open, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 1-10.

Hilton, LG & Azzam, T 2019, ‘Crowdsourcing qualitative thematic analysis’, American Journal of Evaluation, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 1-10.

Ho, ES, Sum, KW & Wong, RK 2018, ‘Impact of gender, family factors and exploratory activities on students’ career and educational search competencies in Shanghai and Hong Kong’, ECNU Review of Education, vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 96-115.

Hout, M 2015, ‘College success and inequality’, Contexts, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 62-63.

Huang, Z, Wang, T & Li, X 2015, ‘The political dynamics of educational changes in China’, Policy Futures in Education, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 24-41.

Hurwitz, M, Mbekeani, PP, Nipson, MM & Page, LC 2017, ‘Surprising ripple effects: how changing the SAT score-sending policy for low-income students impacts college access and success’, Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 77-103.

Hurwitz, M, Smith, J, Niu, S & Howell, J 2015, ‘The Maine question: how is 4-year college enrollment affected by mandatory college entrance exams?’, Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 138-159.

International Student 2019, Test overview. Web.

Johnson, RE, Murphy, M & Griffiths, F 2019, ‘Conveying troublesome concepts: using an open-space learning activity to teach mixed-methods research in the health sciences’, Methodological Innovations. vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 1-10.

Jung, H 2019, ‘The evolution of social constructivism in political science: past to present’, SAGE Open, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 1-10.

Kliem, S, Beller, J, Kröger, C, Stöbel-Richter, Y, Hahlweg, K & Brähler, E 2015, ‘A Rasch re-analysis of the partnership questionnaire’, SAGE Open, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 1-10.

Lai, H 2015, ‘Engagement and reflexivity: approaches to Chinese-Japanese political relations by Chinese students in Japan’, Journal of Current Chinese Affairs, vol. 44, no. 3, pp. 183-212.

Latifi, S, Bulut, O, Gierl, M, Christie, T & Jeeva, S 2016, ‘Differential performance on national exams: evaluating item and bundle functioning methods using English, mathematics, and science assessments’, SAGE Open, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 1-10.

Lewinski, AA, Anderson, RA, Vorderstrasse, AA & Johnson, CM 2019, ‘Developing methods that facilitate coding and analysis of synchronous conversations via virtual environments’, International Journal of Qualitative Methods, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 1-10.

Loscalzo, Y, Raffagnino, R, Gonnelli, C & Giannini, M 2019, ‘Work-family conflict scale: psychometric properties of the Italian version’, SAGE Open, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 1-10.

Ma, Y 2015, ‘Is the grass greener on the other side of the Pacific?’, Contexts, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 34-39.

Maurer, K & Häfner, H 2014, ‘Rasch scaling of a screening instrument: assessing proximity to psychosis onset by the Eriraos checklist’, SAGE Open, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 1-10.

Mayes, J 2015, ‘Still to learn from vicarious learning’, E-Learning and Digital Media, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 361-371.

McLellan, J, Pettigrew, R & Sperlinger, T 2016, ‘Remaking the elite university: an experiment in widening participation in the UK’, Power and Education, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 54-72.

Mei, B, Brown, GT & Teo, T 2018, ‘Toward an understanding of pre-service English as a foreign language teachers’ acceptance of computer-assisted language learning 2.0 in the People’s Republic of China’, Journal of Educational Computing Research, vol. 56, no. 1, pp. 74-104.

Mensah, E 2015, ‘Exploring constructivist perspectives in the college classroom’, SAGE Open. vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 1-10.

Mertens, DM 2015, ‘Mixed methods and wicked problems’, Journal of Mixed Methods Research, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 3-6.

Moseholm, E & Fetters, MD 2017, ‘Conceptual models to guide integration during analysis in convergent mixed methods studies’, Methodological Innovations, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 1-10.

Nowell, LS, Norris, JM, White, DE & Moules, NJ 2017, ‘Thematic analysis: striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria’, International Journal of Qualitative Methods, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 1-10.

Nzabonimpa, JP 2018, ‘Quantitizing and qualitizing (im-)possibilities in mixed methods research’, Methodological Innovations, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 1-10.

Oranye, NO 2016, ‘The validity of standardized interviews used for university admission into health professional programs: a Rasch analysis’ SAGE Open, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 1-10.

Papay, JP, Murnane, RJ & Willett, JB 2015, ‘Income-based inequality in educational outcomes: learning from state longitudinal data systems’, Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, vol. 37, no.1, pp. 29-52.

Poletti, M, Carretta, E, Bonvicini, L & Giorgi-Rossi, P 2018, ‘Cognitive clusters in specific learning disorder’, Journal of Learning Disabilities, vol. 51, no. 1, pp. 32-42.

Poth, C & Onwuegbuzie, AJ 2015, ‘Special issue: mixed methods’, International Journal of Qualitative Methods, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 1-4.

Puigvert, L, Valls, R, Garcia Yeste, C, Aguilar, C & Merrill, B 2019, ‘Resistance to and transformations of gender-based violence in Spanish universities: a communicative evaluation of social impact’, Journal of Mixed Methods Research, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 361-380.

Research Rundown 2019, Mixed methods research designs. Web.

Sanders, J & Ishikura, Y 2018 ‘Expanding the international baccalaureate diploma programme in Japan: the role of university admissions reforms’, Journal of Research in International Education, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 17-32.

Schwemmer, C & Wieczorek, O 2019, ‘The methodological divide of sociology: evidence from two decades of journal publications’, Sociology, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 1-10.

Sherlock, Z 2016, ‘Japan’s textbook inequality: how cultural bias affects foreign language acquisition’, Power and Education, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 73-87.

Shirzadifard, M, Shahghasemi, E, Hejazi, E, Naghsh, Z & Ranjbar, G 2018, ‘Psychometric properties of rational-experiential inventory for adolescents’, SAGE Open, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 1-10.

Sims, D, de Chenu, L & Williams, J 2014, ‘The global agenda: developing international perspectives and critical discourse in UK social work education and practice’, International Social Work, vol. 57, no. 4, pp. 360-372.

Snelson, CL 2016, ‘Qualitative and mixed methods social media research: a review of the literature’, International Journal of Qualitative Methods, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 1-10.

Steinfeld, J 2014, ‘Degree of inequality: China’s discriminatory education system’, Index on Censorship, vol. 43, no. 2, pp. 138-142.

Tsushima, R 2015, ‘Methodological diversity in language assessment research: the role of mixed methods in classroom-based language assessment studies’, International Journal of Qualitative Methods, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 104-121.