Introduction

CRM may be interpreted as a management system that utilizes all available resources – and people equipment, and procedures in order to increase safety and enhance the effectiveness of flight operations (RAS, 1999; Lauber, 1984). Jensen (1995) defines CRM in terms of applying the aviation judgement. He uses the term judgment when referring to single pilot operations and CRM, when referring to multi-person crews in aviation. Helmreich and Foushee (1993) developed a theoretical model of CRM, which takes into account group processes and performance. They define CRM as the function of human factors in the aviation system which reiterates modifying the existing person-machine interface and acquiring not only timely and appropriate information, but also the interpersonal activities (Helmreich & Foushee, p 4).

Background

The involvement of Federal Aviation Administration in CRM began in 1975 when there arose an exception from Federal Aviation Regulation (FAR) 121.409. It allowed LOFT (Line Oriented Flight Training) at Northwest Airlines to train crews in the cockpit under practical settings (Butler, 1991). Subsequently, it was amended by FAR in 1978 to set aside LOFT by any airlines in their training programs.

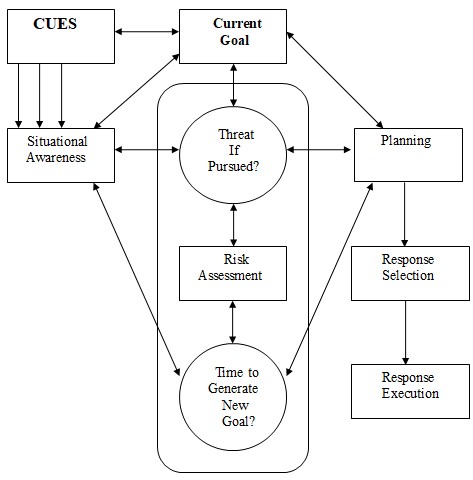

The series of the accidents of the major commercial aircrafts during 1970s indicated that training of pilots left much to be desired and that new strategies had be developed (CAP 719, 2002; Gregorich, Helmreich and Wilhelm, 1990). National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA) sponsored industry workshop titled Resource Management on the Flight deck in 1979 in effort to respond to the lack of crew skills such as, leadership, captaincy and communication (Cooper, White, & Lauber, 1979). In Figure 1(See Appendix), we have tried to explain the correlation between inadequate communication, situation awareness and their effect on wrong decision-making which results in a serious or even fatal accident.

From this seminar, Cockpit Resource Management formulated new techniques with the basic thought of implementing CRM flattened hierarchy to follow in the cockpit. Every crew member was responsible for examining the performance of other team members. This helped to throw light on human mental processes and emotional shortcomings, management and allocation of tasks, the development of command culture (Pat, Karen, Stephen, and Robert, 2008). CRM intends to set out the behaviour that the industry and regulators will require aircrew to demonstrate during the flight. United Airlines took the lead in developing and offering formal training programs in 1980 to improve the interpersonal aspects of flight operations (MacLeod, 2005).

Major changes took place in 1986 when NASA convened another conference on CRM where the term ‘Cockpit’ as in Cockpit Resource Management was changed to ‘Crew’ Resource Management because this term is more comprehensive and it includes the efforts of other personnel like aircraft dispatchers, cabin crew, maintenance personnel, air traffic controllers, security and accident investigation personnel who contribute to the effective use of all available resources (the staff, hardware, and information) that are essential necessary for operating an aircraft safely. This conference also was also aimed at identifying the best practices in CRM training (Orlady and Foushee, 1987). Many airlines participated and established systemized plan with the prospects of improving effectiveness of CRM training. Their efforts were based on the reports presented on the implementation of CRM. Two proposals were considered: 1) behavior-based training of specific teamwork skills including communication, situational monitoring, decision-making, and stress management; 2) the use of behavioral models to make a difference between effective and ineffective teamwork behaviors in the cockpit. This helped the pilots come into a closer understanding of the validity of CRM training.

CRM and Culture

Culture gives us signs, stimulus and evidences on how to behave in normal and novel situations (Maurino, 1994). It impacts on the communication among subordinates and superiors and it even influences the use of automotive systems (Helmreich, Merritt & Sherman, 1997). Professional culture, discussed in table 3 which explains the subdivisions of national culture, is directed to promote a practical awareness of personal limits and capabilities through CRM training. Further, Merritt (1993, 1994) supplements implications of cultural preferences: Individualism inversely correlated to Power Distance, two of Geert Hofstede’s (1980) cultural dimensions have been discussed in Table 4 in connection with such CRM concepts as communication, leadership and authority and behavioral implications.

II CRM Concepts/Skills

Definition of a CRM skill

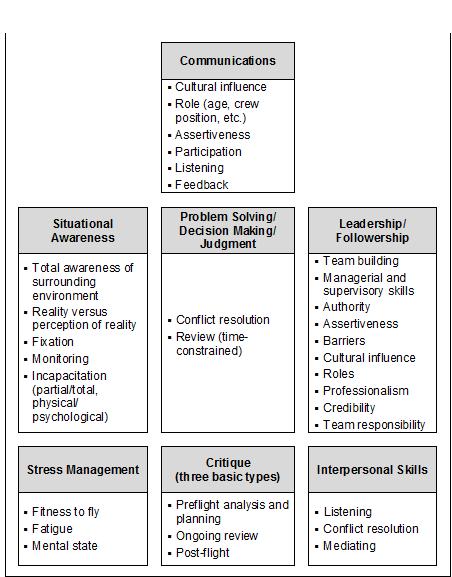

Cognitive skills are the mental processes used for gaining and maintaining situational awareness, solving problems and taking decisions. Interpersonal skills are communications and a range of behavioral activities associated with teamwork. These concepts are explained in figure 2 as they also constitute domain of CRM training.

Through the process of experiential learning, the Cognitive and Interpersonal CRM skills are prepared to reproduce an individual’s past behavior in a given organizational situation (CAP 737, 2006). In this way, an individual acquires sufficient knowledge, which forms a rational basis for reacting in an effective way further when faced with related situations. These skills are the automatic behavioral responses retrieved from memory faster than stored information held in memory structures (MacLeod, 2005).

From an operational point of view, a skill is an element closely linked with a specific set of subtasks and performance. Proctor and Dutta (1995) believe that skill is a goal oriented; well-organized behavior acquired through practice. Majority of the CRM concepts necessitate complex cognitive skills that involve problem solving, efficient grouping of information, and the use of specialized forms of mental representations. These skills involve time and space to develop and as a rule they are very specific within the context of the aviation industry.

CRM skill Issues in the Operational environment

There is an urgent need for a common language or glossary of terms used in communication between aircraft and ground personnel. The staff includes all human resources working towards the tasks related to airplane flying and maintenance.

The term ‘Team’ places emphasis on effective coordination of crew members from the beginning of a task until completion. Although CRM training is supervised in the form of teams, culture and behavioural characteristics need room for improvement. The concept of synergy is crucial for enhancing the commitment towards absorbing CRM skills at team level. Team efforts might be intermingled while some tasks need team participation in decision making and some must be carried out individually, still, the importance of right guidance cannot be underestimated because it might establish good team work. Hence there should be awareness on the interrelationships and prioritizing (SKYbrary, n.d) Company rules, procedures and norms follow the course of action and used in operations. These norms are missed or neglected during any course of action. Therefore, there is need for proper identification of norms to make up to the expectations desired. ‘Pilot’ is the captain and resourceful person in the cockpit. Past experiences confine the pilot to hold the statutory and regulatory position in command, team leader and commander, who holds information and resources. Also, there are countable numbers of accidents because of the absence of such quality as ‘fit to fly’.

CRM skills to achieving appropriate Operational Behavior through

CRM training

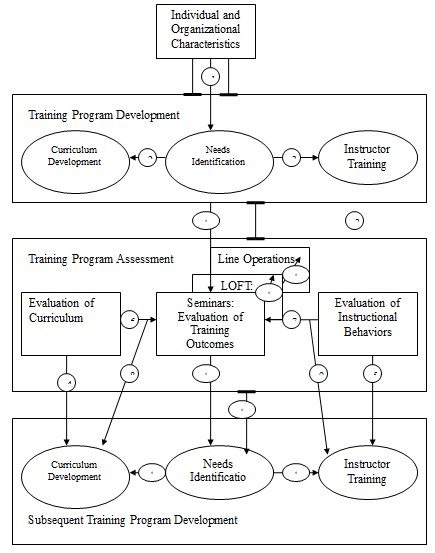

The goal of CRM training is to establish the expected CRM behaviors. It aims to reconstruct the conventional workplace behavior. Moreover, it checks the safety achieved as an outcome of competent performance. CRM training focuses on situational awareness, communication skills, teamwork, task allocation and decision making delivered within a broad framework of Standard Operating Procedures. The level of CRM instruction required for each stage of training in the figure 3 provide a base for CRM training syllabus for flight crew. It covers basic concepts of human factors related to aviation and provides tools necessary to apply these concepts operationally. CRM training is a long-term development process that encompasses a varied set of training resources. The classes are interactive and experiential; we can single out such forms as self-study, classroom awareness training, modeling, classroom skills training, continual skills practice in both classroom and simulator, and practice or coaching during flying operations (Flin, O’Connor and Crichton, 2008).

Objectives of CRM Training

The major objective of CRM training is to bring improvements into crew and management understanding and knowledge of human factors. Apart from that it is supposed to develop CRM skills and attitudes, which contribute to competent performance and handling aircraft operations.

In an attempt to determine CRM skills, NASA workshop developed curriculum (Orlady and Foushee, 1987) which included non-technical skills else called as CRM skills or behavioural characteristics. The skills like communication, interpersonal relations, decision-making, situation awareness, coordination and adaptability are described in Table 5 with corresponding definitions (Bowers, Tannenbaum, Salas and Volpe, 1995). Harris and Muir (2005) point out that the extension of team-related theory will contribute to the design and delivery of CRM training of teamwork, team competencies (knowledge, skills and attitudes) and shared mental models.

Teamwork: Helmreich (1991) maintains that in the vast majority of cases, it is the team ( not the aircraft or the individual pilots) is the source of the accidents and incidents. Team work competencies, as put forward by Canon-Bowers and colleagues (1995), are well described in Table 6 who identifies 3 types, namely, knowledge competencies, skill competencies and attitude competencies. These competencies are the characteristic features or qualities that team members must possess in order to merge into successful crew. Hackman (1993) suggests three facts about cockpit crews: cockpit crews are teams, the captain is the team leader and the cockpit crews are richly entwined with the organizational, technological and regulatory contexts in which they operate. These facts determine the training of the pilot and influence the managed by the established policies and practices.

Advanced Qualification Program (AQP)

The Advanced Qualification Program (AQP) was introduced to allow airlines to tailor training programs which would fit the companies needs while still both CRM skills and Line Oriented Flight Training (LOFT) (a simulation- based training) be provided to all crews. It is also assessment program based on proficiency training. It should be noted that the proficiency objectives are systematically developed, maintained, and validated (Don and Helen, 2005).

Advanced Crew Resource Management (ACR)

The Advanced Crew Resource Management is an all-inclusive implementation package of CRM procedures, training of the instructor/evaluators, and training of crews. Furthermore, it comprises regulated assessment of crew performance, and an ongoing implementation process providing an integrated form of CRM by integrating CRM practices with Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) (Seamster, Davis, Holt and Schulz, 1998). ACRM training provides airlines with unique CRM solutions tailored to their operational demands.

Model of CRM training program assessment

Gregorich and Wilhelm (1993) propose two models of assessment:

- Cross-sectional: This kind of evaluation is made across disparate groups (trained Vs. untrained, curriculum A Vs. curriculum B). It is relatively simple and inexpensive. This technique compares the data of the outcomes of two curricula from each training session. This information is bundled and identified before lodging into the database. This model basically resolves the problem of data comparison.

- Longitudinal designs: This assessment compares data of individuals across time. For example, pre-and post- training attitudes, attitudes change scores and behaviors in LOFT. It has the ability to track progress and development in performances of individual students at various stages training. A more challenging is linking of data across components of training; in this confidentiality of personal and organization data has to be the topmost priority.

These distinctions are represented in figure 4 as a model of assessment of CRM training program (Refer to the Appendix). It depicts CRM training program’s 3 phases of development: Initial awareness-training program development, recurrent practice and feedback- training and subsequent reinforcement program.

The assessment of CRM skills

Flin O’Connor and Crichton (2008) view assessment as the processes of observing, recording, interpreting and evaluating individual performance usually against a standard determined by a professional body, a company, or a safety regulator.

Assessment of behavioral change is known as behavioural markers. They are observable, non-technical behavior that is conducive to superior or substandard performance in workplace. These behavioral markers are derived from analysis of data from multiple sources regarding performance that contributes to successful and unsuccessful outcomes, for example, accident investigation, confidential incident reporting systems, incident analysis, simulator studies, task analysis, interviews, surveys, focus groups. Behavioral markers are evaluated according to a set of criteria like communication process, building and maintenance of flight cooperation, workload management and situation awareness (CAP 737, 2006).

Additionally, there is a growing necessity to examine those CRM skills, which follow success rate. It is of the crucial importance to determine whether current training programs meet the standards of the operational environments, because these standards are dynamic in nature and they constantly evolve. The outcomes of training program are affected not only by its curriculum and teaching methods, employed by the instructor, by the policy of the organization, in which the program is being implemented (Helmreich and Wilhelm, 1991). Thus, it is quite possible to say that the concept of CRM skills is not universal and therefore it can vary depending on a particular company, the same goes for CRM training.

Researchers have found out that the systematic training of raters in CRM concepts made a significant difference in the quality of ratings and scale use (e.g., raters using the entire scale) as compared with raters who were trained less systematically (Helmreich, Chidester, Foushee, Gregorich, & Wilhelm, 1990). These ratings of observed work behavior (called as Behavioral marker systems) are used for performance appraisal, selection and task analysis. The assessment is carried through observing the behavior at work or in a simulator usually in a team setting at individual level. There are also group-level assessment systems to rate crew’s performance through Line Oriented Safety Audit (LOSA).

NOTECHS Behavioral Markers

According to JAR OPS NPA 16 (2001) the progress of flight crew must be assessed on their CRM skills according to standards set by the authority and published in the operations manual. Such assessments are the indispensible condition for continuous reinforcement of training of every crew member. Thereby, they must be used to further develop and improve the CRM training system.

CRM skills can also be called as non-technical skills. Assessment of CRM skills refer to flight crew member’s behaviors in the cockpit not directly related to aircraft control, system management and SOPs. Joint Aviation Requirements (JAR) specifies two design requirements: assessment of individual pilot and suitable for the use across Europe by both small and large operators. These parameters required by JAR were not met by already-existing training programs. Therefore, a research team, comprising members from DLR (Germany), IMASSA (France), NLR (Netherlands) and University of Aberdeen (UK), was organized to work on NOTECHS (Non-Technical Skills) project. Figure 5 explains the NOTECHS – Co-operation, Leadership and Managerial Skills, Situation Awareness and Decision Making with example of behaviors and the rating scale (Hausler, Klampfer, Amacher and Naef, 2004).

Behavioral Markers by University of Texas (UT)

The first behavioral marker system, represented by Figure 6, (in the Appendix, we lists currently used markers, showing ratings during the phase of flight, followed by the ratings for each phase of flight) was developed for pilots (NASA/UT Behavioural Markers). It was carried on by the University of Texas Human Factors Research Project during 1980s (Flin, O’Connor and Crichton, 2008). This project was supported by a grant from the FAA and, was included by the FAA as an addition to its Advisory Circular on CRM (AC-150A). This project had to fulfill two tasks : 1) to evaluate the effectiveness of CRM training as measured by observable behaviour; 2) and to define the scope of CRM programmes.

Airlines used these markers to make their grading of crew performance more accurate and objective; for that purpose, detailed data were collected. This information was also incorporated in a rating form, known as the Line/LOS checklist for systematic observations, and used in Line Operations Safety Audit (LOSA) for crews in normal flying flights. Hence, the rating form was modified to assess the markers for each phase of flight (Helmreich et al., 1989a).

LMQ

LMQ is a specialist management consultancy involved in developing standards and training programmes for flight or cabin crew, engineers and air traffic controllers to help these operators to perform even more effectively and safely. Several UK airlines use LMQ CRM standards, founded on observable actions, on which trainers and examiners rely during their assessments of line crews presented in Figure 7. These standards are framed according to 5 year research, accident and incident analysis, experience by crews when practicing CRM skills (Seamster, Boehm-Davis, Holt and Schultz, 1998).

Conclusion

The function of operational concepts, focused in the CRM training involves such steps as search of appropriate operational information, communicating proposed actions, problem solving, decision making, critical evaluation of actions taken and decisions reached. These procedures are necessary for the assessment their behavior and the improvement of crew performance. Good training for everyday operations does have strong impact on the individuals during high workload or high stress. Taking proper action and reflecting appropriate behavior during emergency conditions is what a crewmember inherits from CRM training.

ICAO steps are employed to improve conditions by regulating English language as the medium of instruction in the non-English speaking countries. National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) makes CRM training compulsory criteria for certification of the pilots as this measure may help to encountering some of the operational issues. The assessment must also be viewed as a process of discovery that guiding future shortcomings and accidents or incidents. Improvements in the measurement of assessment criteria will result in better needs identification, enriched conceptualization of CRM skills (related to mental attitudes and motives) and advances in measurement as well as evaluation and training theories. Achieving the combination of better definitions of CRM skills and improved measurement methodologies will be important steps in the identification of definitive standards of CRM behaviors.

References

Butler R. E. ( 1991). Lessons from cross-fleet/cross airline observations: Evaluating the impact of CRM/LOS training. In R. S. Jensen (Culture in the cockpit: A multi-airline study of pilot attitudes and values. In R. S. Jensen (Ed.), Proceedings of the Eighth International Symposium on Aviation Psychology (p.676). Columbus, OH: The Ohio State University.

Canon Bowers, J.A., Tannenbaum, S. I., Salas, E., and Volpe, C.E. (1995). Defining team competencies and establishing team training requirements. In Guzzo, R., Salas. E. et al. (Eds.). Team effectiveness and decision making in organizations. San Francisco, CA. Jossey-Bass.

CAP 719, Fundemental Human Factors Concepts. Issue 1. Civil Avaition Authority. 2002.

CAP 737, Guidance for Flight Crew, CRM instructors (CRMIS) and CRM instructor-Examiners (CRMIES). Crew Resource Management (CRM)Training. Issue 2. Civil Avaition Authority. 2006.

Cooper, G. E., White, M. D., and Lauber, J. K. (1979). Resource management on the flight deck: Proceedings of a NASA/industry workshop (NASA CP-2120). Moffett Field, CA: NASA-Ames Research Center.

Daniel E. maurino. (1999). Crew Resource Management: A Time for Reflection. In Daniel J. Garland, John A. Wise and V. David Hopkin’s Handbook of aviation human factors. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Federal Aviation Administration (1990). Line operational simulations: line oriented flight training, special purpose operational training, line oriented evaluation. Washington, DC: Federal Aviation Administration; 1990. FAA Advisory Circular No. (FAA) 120-35B.

Federal Aviation Administration (1991): Advanced qualification program. Washington, DC.

Federal Aviation Administration. 1991. FAA Advisory circular No. (FAA) 120-54.

Gregorich SE, Helmreich RL, Wilhelm JA. (1990). The structure of cockpit management attitudes. Journal of Applied Psychology; 75: 682-90.

Gregorich SE and Wilhelm JA. (1993).Crew Resource Management Training and Assessment. In Earl L. Weiner, Barbara G. Kanki and Robert L. Helmreich. Cockpit Resource Management. Academic Press.

Gregorich SE, Wilhelm JA, Helmreich, R.L., Chidester, T. R. (1990). Preliminary results from The evaluations of cockpit resource management training: Performance ratings of flight crews. Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine, 61, 576-579.

Harris, Don and Muir, C. Helen. (2005). Contemporary issues in human factors and aviation safety. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.

Helmreich, R. and Wilhelm, J. (1987). Evaluating Cockpit Resource Management Training. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Symposium on Aviation Psychology (p.440-446). Columbus, OH: The Ohio State University.

Helmreich, R.L., Chidester, T. R., Foushee, H. C., Gregorich S. E., and Wilhelm JA. (1989a). Critical Issues in Implementing and reinforcing cockpit resource management (NASA/Universit of Texas technical report 89-5). Austin.

Helmreich, R. and Foushee, C. (1993). Why crew resource management? In E. L. Weiner, B. G.

Kanki, & R. L. Helmreich (Eds.). Cockpit resource management. (pp. 3-45). San Diego: Academic Press.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture ‘s consequences: International differences in work-related values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

JAR-OPS Subpart N (Amendment 3, 2001)(previously NPA OPS 16).

Jensen, R. (1995). Pilot judgment and crew resource management. Burlington: Ashgate.

Lauber, J. K. (1984). Resource Management in the Cockpit. Air Line Pilot, 53, 20-23.

Merritt, A.C. (1993). The influence of national and organizational culture on human performance. Invited paper at an Australian Aviation Psychology Association Industry Seminar, 1993. Sydney, Australia: The Australian Aviation Psychology Association.

Merritt, A.C. (1994). Cultural Issues in CRM training. In International Civil Avaition Organization (Ed), Report of the Sixth ICAO Flight Safety and Human Factors Seminar, Amsterdam, Kingdom of the Netherlands, 1994 (pp. 326-343). Montreal, Canada: Editor.

MacLeod, Norman. (2005). Building safe systems in aviation: a CRM developer’s handbook. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.

O’Hare. 1992. The “artful” decision maker : A framework model for aeronautical decision making. International Journal of Aviation Psychology. 2. 175-191.

Orlady HW, Foushee HC. (1987). Cockpit resource management training. NASA Conference Publication No. NASA-CP-2455. Moffett Field, CA: NASA-Ames Research Center.

Pat Croskerry, Karen S Cosby, Stephen M Schenkel, Robert L Wears. (2008). Patient Safety in Emergency Medicine. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Proctor, R. W., & Dutta, A. (1995). Skill acquisition and human performance. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Richard J. Hackman. (1993). Teams, Leaders and Organizations: New directions for Crew-oriented Flight Training. In Earl L. Weiner, Barbara G. Kanki and Robert L. Helmreich. Cockpit Resource Management. Academic Press.

Rhona H. Flin, Paul O’Connor, Margaret Crichton. (2008). Safety at the sharp end: a guide to non-technical skills. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.

Royal Aeronautical Society, 1999. A Paper by the CRM Standing Group of the Royal Aeronautical Society, London.

Ruth Hausler, Barbara Klampfer, Andrea Amacher and Werner Naef. (2004). Behavioral Markers in Analyzing team Performance of Cockpit crews. In Rainer Dietrich, Traci Michelle Childress, GIHRE Project, Group interaction in high risk environments. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.

Sherman, P.J., Helmreich, R.L., & Merritt, A.C. (in press 1997). National culture and flightdeck automation: Results of a multi-nation survey. International Journal of Aviation Psychology.

SKYbrary. (nd). CRM Skills Training. Web.

Tannenbaum, S. I., & Yuki, G. (1992). Training and development in work organizations. Annual Review of Psychology, 43, 399-441.

Thomas L. Seamster, Deborah A. Boehm-Davis, Robert W. Holt, and Kim Schultz. (1998).

Developing Advanced Crew ResourceManagement (ACRM) Training:A Training Manual. Federal Aviation Administration. AAR-100 Tony Kern. (2001). Culture, Environment, and CRM. McGraw-Hill Professional.

Wilhelm, J. (1991). Crew member and instructor evaluations of line oriented flight training. Proceedings of the Sixth International Symposium on Aviation Psychology (p.676). Columbus, OH: The Ohio State University.

Figures

Tables

Table 1: Recorded accidents and incidents during 1970s

Table 2. CRM Generations

Table 3. National Subcultures

Table 4. Cultural Preferences: Individualism inversely proportional to Power Distance

Table 5. CRM skills and Definition

Table 6. Teamwork competencies (knowledge, skill and attitude based competencies)