Executive Summary

This report reviews research on mass incarceration or imprisonment. Its anticipated outcome is to help in reforming Florida and the American justifications with reference to the number of incarceration times for wrongdoers within the criminal justice system. The State of Florida falls in the 10th position in terms of incarceration. It falls below Louisiana, which has the highest incarceration rate.

Louisiana has significantly higher rates of incarceration compared to States such as Minnesota and North Dakota, which are the only similar-sized regions that have been found to record the lowest incarceration rate (Wagner, Sakala, & Begley, 2016). Incongruence is obvious between the States with lower incarceration rates and the ones that have recorded higher incarceration levels. This report evaluates this divide.

Through concrete research, it brings the political issue to light. The audiences being sought are lawmakers, the legislative body, and state governments. Calls are made for the audience to consider bringing the number of incarceration to similar levels throughout the United States. It advocates for the necessity to bring the rates down beginning with states with the highest rates of incarceration, namely, Louisiana and Florida. It also proposes the need for obtaining accurate rates of incarceration, for instance, parole and mental illness reports (Florida Commission on Offender Review, 2014).

Introduction

Do states with the highest rates of incarceration have higher levels of crimes that lead to a conviction? Even though the response to such an interrogative cannot be put forward explicitly, different policy frameworks and disparities in the dominant political views of any state may contribute to the witnessed variations in incarceration rates among States. This hypothetical position underlines the ultimate significance of this paper. It suggests the need for a policy that harmonizes the political and ideological positions from Republicans or Democrats across different states to bring down the rate of incarceration.

Thus, a reduction of the incarceration rates attracts the development of the appropriate policy framework that embraces alternative mechanisms for punishing some crimes, which are currently handled and/or rehabilitated through incarceration. All States in America, especially those that have recorded a high rate of incarceration, for instance, Florida and Louisiana, should embrace such a policy. Felony and other offenses that contribute to mass incarceration may be addressed using alternative strategies such as community rehabilitation through an intermediate sanction policy framework.

Policy Options and Research

The term incarceration refers to the state of one being locked up in prison. In the US, incarceration is deployed as the mechanism for punishing and/or rehabilitating offenders who are found guilty of felony crimes coupled with other offenses. The term mass incarceration implies a high number of people who are confined in prison compared to the total population of any State (Taibbi, 2014). Tasliz (2011) asserts that America relies heavily on incarceration to rehabilitate or punish felony crimes, a fact that cannot be questioned. He further argues that the phenomenon is explosive to the extent that the vocabulary ‘mass incarceration’ has been coined to describe it.

Different nations and States have different rates of incarceration. The US possesses the largest population of incarcerated citizens (Institute of Criminal Policy Research, 2016; Mahapatra, 2014). In terms of incarceration per capita, it falls in the second position after Seychelles. Although the nation (Seychelles) has a population of about 92,000, about 785 people were incarcerated in 2014 (Institute of Criminal Policy Research, 2016). In the case of the United States, for every 100,000 people, 698 were incarcerated in 2013 (Institute of Criminal Policy Research, 2016). Louisiana has the highest rate of incarceration. Indeed, the statistical findings on the incarceration rate in the US vary according to States.

The most reliable source of data that can demonstrate the significance of the problem of mass incarceration in the United States is the US Bureau of Justice Statistics (BSJ). In 2013, the organization reports, “2,220,300 adults were incarcerated in the US federal and state prisons and county jails in 2013– about 0.91% of adults (1 in 110) in the US resident population” (Glaze & Kaeble, 2014, p.10).

The organization further indicates that in the same year, 1 out of 51 citizens were on parole or placed on probation. The implication of these statistics is that 1 out 35 residents in the US were either on parole, serving a jail term, were in detention centers, or placed on trial. Hence, the high prevalence of mass incarceration in punishing or rehabilitating felony convicts may call for the need to establish other policy alternatives, for instance, putting petty offenders on community-based correctional facilities.

Indeed, Glaze, Kaeble, Anastasios, and Minton (2015) inform that the number of young offenders placed on correctional systems reduced by more than 52,000 with reference to the 2013 and 2014 data. However, this finding does not imply that crime rates reduced during this period. Indeed, Glaze et al. (2015) argue that the number of incarcerated adults was on the rise in 2014 compared to 2013.

In 2013, the number of juveniles held in youthful detention facilities stood at 54,148 (Sickmund, Sladky, Kang, & Puzzanchera, 2014). The problem of mass incarceration in the USA is amplified by the fact that the US residents can still be incarcerated because of debts, even though debtors’ prisons were scrapped off (Genevieve & Adrienne, 2012). Driven by this concern, Timothy (2015) observes that various jails in the US serve the role of warehousing the poor, drug addicts, mentally ill persons, and people with financial challenges, a situation that limits their capability for posting bail.

Human Rights Watch (2014) echoes similar concerns by noting that laws labeled ‘tough-on–crimes’ that found their way into the US judicial criminal system in the 1980s have led to the filling of American jails with a large number of nonviolent people. It indeed suffices to establish an alternative policy that can reduce mass incarceration, especially of nonviolent offenders.

Different states have recorded a history of specific political views or inclinations. For example, Minnesota has a history of democratic political inclination while Republicans dominate Louisiana (Croockett, 2016). Such inclinations have had ramifications on mass incarceration in the US. Chettiar (2015) supports this view by arguing that Republicans have now shifted their policy from leaning toward President Regan’s staunch support for policies aimed at fighting drugs to now supporting Democrats in a call for judicial reform.

Indeed, States such as Minnesota, which traditionally voted for autonomous political views, have lower rates of mass incarceration compared to Louisiana that has an incarceration rate of 867 for every 100, 000 individuals (Archambeault & Donald, 2009), yet the two States are almost the same in terms of their population sizes.

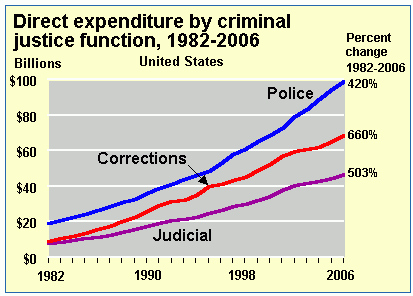

Maintaining a high population in prisons requires heavy expenditure. Taslitz (2011) suggests, “The sheer cost of maintaining this prison state may indeed be making it buckle somewhat under the weight of the incarcerates’ fiscal burden” (p.332). However, Wolff and Gottschalk (2008) counter this argument by positing that amid the different prevalence levels of mass incarceration in different states, the reformatory state continues to survive in the USA. Hence, a mechanism for reducing it requires the involved parties to address its key drivers. One such driver is the availability of funds to run prisons in the USA as shown in Figure 1 below.

The need to increase such funds was supported by policies that campaigned for tough responses to crimes. For example, in 1992, during his presidential campaign, President Clinton promised to react toughly to crimes. He delivered his promise through legislation facilitating the flow of billions of dollars to different States. This plan would help in increasing and managing the large population of inmates in American prisons.

Conclusion

An obvious incongruence exists between American regions with lower incarceration rates and the ones that have elevated imprisonment levels. The paper has argued that political-ideological positions from Democrats and Republicans have implications on the prevalence of incarceration rates in any State in the US. Republicans have history-supported policies for increasing incarceration as a mechanism for punishing felony crimes coupled with other offenses, despite today’s change of support to such policies.

The paper suggests that this situation may explain why States such as Louisiana, which have traditionally upheld the Republican political views, have the highest incarceration rate in the US. While the phenomenon of mass incarceration persists in the US, the issue is a necessary cause of alarm that requires urgent attention by lawyers, the legislative body, government, human rights entities, and policymakers in all states across the US, especially those with high incarceration rates, including Louisiana and Florida.

Policy Recommendations

Option 1: Releasing Wrongfully Convicted Persons

A policy initiative aimed at reviewing determining cases in which the probability of wrongful conviction is high can incredibly help in the reduction of incarceration rates in the United States and consequently a decrease in mass incarceration in Louisiana and Florida. Such implications depend on the evidence concerning the success of such a policy. Norris, Bonventre, Redlich, and Acker (2011) argue that the number of people identified as wrongly convicted increases as more cases continues to be revisited.

Since the 1989 successful prosecution of the first case involving DNA testing in the US, Innocence Project, an advocacy group that fights for the rights of wrongly convicted persons, reveals that 272 people were exonerated in 2011 (Norris et al., 2011). The organization only considers cases where DNA evidence has been retained after conviction to permit re-testing. It estimates that such cases only account for about 10% of all criminal convictions in the US (Norris et al., 2011).

According to Acker (2013), advocates of reform in judicial systems argue that DNA testing only encompasses a conclusive approach to a successful conviction in a few criminal cases. The observation suggests many more wrongfully convicted people in prisons whose ability to prove their innocence is void due to the inexistence of any retained DNA evidence. Indeed, DNA testing is only important in crimes involving DNA exchanges such as murder and rape.

In most cases, it is only reliable where murder preceded a rape. In this case, sufficient DNA testing becomes available. Nevertheless, this claim does not imply that DNA must always be preserved even in these two classes of crimes. It does not give valid results in all situations in terms of identifying the crime perpetrators (Garrett & Neufeld, 2010).

The prevalence levels of wrongful convictions may be more than the figures cited by the Innocence Project. In 2007, Risinger, a law professor at Seton Hall, studied 328 different cases of exoneration involving convicts of felonies such as murder and rape from 1989 to 2003. In his study, he also compared these cases to various other incidents that involved rape or murder, in which DNA was a crucial factor in their successful prosecution (Radley, 2014).

He deduced that the total number of people convicted to death accounted for 1% of the entire prison population in the US and 22% of all exonerated people. Hypothetically, assuming that persons who are wrongly convicted to life imprisonment also account for 1% similar to the case of those convicted to death as Resinger suggests, a 2% (about 46,000) of US prisons’ population would have been wrongly convicted to either life imprisonment or death penalty by 2008.

The above hypothetical figures of wrongful convictions in the US attract high criticism with commentators arguing that they are too high. For instance, Joshua Marquis, Clatsop County’s DA, criticizes the arguments raised by Resinger and statistics from the Innocence Project. He maintains that although wrongful convictions may occur, they are uncommon. He further suggests that he would even consider resigning if he, for sure, knew 2 to 5% of all prisons’ population was innocent (Radley, 2014).

However, whatever the actual number of wrongful convictions, they are a necessary cause of alarm, especially by noting the upwards trend of the number of cleared cases of wrongful convictions (Radley, 2014). Hence, a review of all wrongful convictions can incredibly reduce the problem of mass incarceration, especially in States with harsh crime policies.

Option 2: Community-based Rehabilitation

Justice is delivered to match the threshold of the committed offense. Therefore, incarceration in States such as Florida and Louisiana can be reduced using a policy directive for putting petty offenders into community rehabilitation facilities through intermediate sanctions. Indeed, for a state interested in seeking to reduce incarceration rates, an intermediate sanction or prisons are more appropriate depending on the crime committed.

For example, a terrorist who bombs 1000 people leaving them dead while he or she narrowly escapes death can only be an aggravated source of national and international security when an intermediate sanction is deployed to punish him or her. Such a person needs not to be in contact with other people who he or she can potentially harm or citizens who he or she can conspire to commit another deadly crime.

Depending on the threshold of the crime, intermediate sanctions for selected groups of offenders can be effective in reducing high incarceration rates in Louisiana and Florida. Instead of bringing petty offenders in contact with hardcore criminals who can train them to commit serious crimes when released to the communities, an intermediate sanction is effective since it reduces the chances of recidivism (Shalev, 2009). There should be no worry that intermediate sanctions can expose communities to risks. The exercise can be done in a manner that offenders are monitored for them not to cause safety challenges to the communities that integrate them. This way, high incarceration rates also become possible to reduce.

The State of California provides an important benchmark for the effectiveness of a community-based correctional policy directive. California Welfare-To-Work-Act, enacted in 1997, led to the creation of the Comprehensive Youth Service Act, which was meant to provide “Country Probation Departments (CPDs) with federal Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) funds to be used to help attain overarching federal TANF goals by providing services to youths and their families” (Turner, Davis, Steinberg, & Fain, 2003, p. 11). Services provided at the juvenile halls influenced the youths in various ways. Through the CYSA/TANF, many counties argued that they experienced observable changes with real impacts on persons who were seeking services from the juvenile halls.

In terms of collaboration, mental health and drug abuse programs were implemented in various counties. Such programs were instrumental in helping to provide mechanisms for reforming juveniles since substance abuse is one of the major drivers of youths’ engagement in a felony (Grady, 2012). CYSA/TANF curriculum also provided funds that were deployed to enhance activities, which were pivotal in the achievement of other goals of juvenile service as intended by the CYSA/TANF legislation.

The goals included the investment of CYSA/TANF funds in teaching at-risk youths subjects such as anger management, counseling, and even educational advocacy mechanisms among others. This strategy is desirable and appropriate in reducing the probability of increased mass incarceration in the State of California. Such success will influence the situation in Louisiana and Florida, which have a high rate of mass incarceration.

References

Acker, J. (2013). The flipside injustice of wrongful convictions: When the guilty go free. Albany Law Review, 76(3), 1629-1672.

Archambeault, W., & Donald, D. (2009). Cost effectiveness comparisons of private versus public prisons in Louisiana: A comprehensive analysis of Allen, Avoyelles, and Winn correction centers. Journal of the Oklahoma Criminal Justice Research Consortium, 4(1), 1-10.

Chettiar, I. (2015). Republicans and Democrats agree: End mass incarceration. Web.

Croockett, Z. (2016). How your state voted in the past 15 elections. Web.

Florida Commission on Offender Review. (2014). Year end summary statistics. Web.

Garrett, B., & Neufeld, P. (2010). Invalid forensic science testimony and wrongful convictions. Virginia Law Review, 95(1), 1-97.

Genevieve, L., & Adrienne, R (2012). Confining social insecurity: Neoliberalism and the rise of the 21st century debtors’ prison. Politics and Gender, 8(1), 25–49.

Glaze, L., & Kaeble, D. (2014). Correctional population in the United States. Washington, DC: US Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Glaze, L., Kaeble, D., Anastasios, T., & Minton, T. (2015). Correctional populations in the United States, 2014. Washington, DC: U.S Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Grady, S. (2012). Civil death is different: An examination of a post-Graham challenge to felon disenfranchisement under the Eighth Amendment. The Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology, 102(2), 441-470.

Human Rights Watch. (2014). National behinds bars: A human rights solution. London: Routledge.

Institute of Criminal Policy Research. (2016). Highest to lowest- prison population rate. Web.

Mahapatra, L. (2014). Incarcerated in America: Why are so many people in the US prisons? New York, NY: International Business Times.

Norris, R., Bonventre, C., Redlich, A., & Acker, J. (2011). Than that one innocent sufferer: Evaluating state safeguards against wrongful convictions. Albany Law Review, 74(3), 1301-1364.

Radley, B. (2014). Wrongful convictions. Web.

Shalev, S. (2009). Supermax: Controlling risk by solitary confinement. Cullompton, England: Willan Publishing.

Sickmund, M., Sladky, J., Kang, W., & Puzzanchera, C. (2014). Easy access to the census of juveniles in residential placement. New York, NY: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

Taibbi, M. (2014). The divide: American injustice in the age of the wealth gap. New York, NY: Spiegel and Grau.

Taslitz, A. (2011). The criminal republic: Democratic breakdown as a cause of mass incarceration. Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law, 9(1), 133-193.

Timothy, W (2015). Jails have become warehouses for the poor and addicted, a report says. New York, NY: New York Times.

Turner, S., Davis, L., Steinberg P., & Fain, T. (2003). Evaluation of the CYSA/TANF program in California: Final report. Santa Monica, CA: RAND.

Wagner, P., Sakala, L., & Begley, J. (2012). States of incarceration: The global context. Web.

Wolff, N., & Gottschalk, M. (2008). The prison and the gallows: The politics of mass incarceration in America. Journal of Health Policy, 33(1), 332-337.