Description of the issue

“One man, one vote” — this statement is used to describe the American democracy that presupposes the right to vote for every individual, regardless race and socio-cultural background. Throughout the history, America practiced the limitations of rights for particular groups of people. Although the country demonstrates its ability to eliminate racial discrimination, other related issues exist. Disenfranchisement of ex-felons may be regarded as a new form of discrimination of basic human rights.

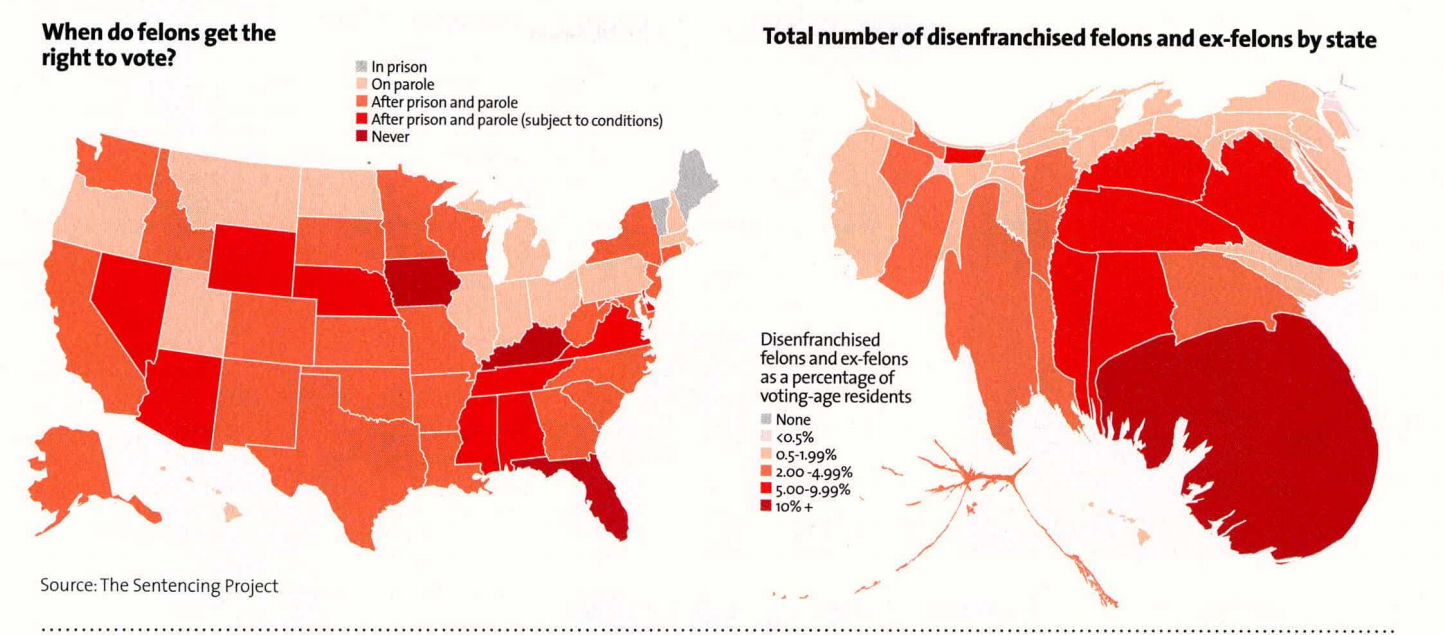

Laws regarding felon disenfranchisement prohibit the right to vote for convicts who have served their sentences. This prohibition is a collateral consequence of the conviction of the crime. This law varies from state to state. The variation usually concerns the process of returning the right to vote and the accompanying procedures. Thus, most states support the law that allows felons to receive the right to vote after prison and parole (“The Unforgiving State”, 2015). The following pictures demonstrate the number of individuals without the right to vote as well as rules for receiving this right (“The Unforgiving State”, 2015).

Florida has the most severe rules concerning ex-felon disenfranchisement. The proportion of African-Americans who cannot vote because they are former felons comprises almost 20%. Residents of Florida may lose the right to vote for different crimes including the presentation of the forged lottery ticket (“The Unforgiving State”, 2015).

The practice of disenfranchisement is not new. It was known in the first civilizations. For instance, people were exiled from the public life in Greece for the commitment of the crime. It was known as atima or dishonor. Felons were not allowed to vote and conduct other activities that were guaranteed to every free citizen (Hamilton-Smith & Vogel, 2012). In the United States of America, the 1965 Voting Rights Act (VRA) was a step towards the democratic citizenship. The VRA repealed the disenfranchisement of African-Americans, and it was a significant development of the system of law. Over the last few decades, the number of felons increased substantially in the U.S., and it resulted in the situation that about five million people could not vote because they were ex-felons in 2010 (Hamilton-Smith & Vogel, 2012).

In my opinion, such situation challenges the democracy of the country. Individuals who have served their sentences should not be deprived of the right to vote and, consequently, the right to become active members of society. Still, the issue is rather controversial. I find it useful to analyze opinions both for and against disenfranchisement to be aware of the most significant aspects of the issue.

Supporters of disenfranchisement argue that felons cannot be trusted even after prison. There is always a risk that they may be corrupted for voting in elections (Manza, Brooks, & Uggen, 2003). The other factor used by supporters is about “the purity of the ballot box”. Some people believe that ex-convicts’ participation in voting taints the politics of the state and government. This suggestion concerns “moral qualifications” of voting that have been discussed for more than hundred years (Sigler, 2014). Also, some ideas do not allow restoring rights to criminals who have committed violent crimes, otherwise “rapists, murderers, robbers, and even terrorists or spies would be allowed to vote” (Manza et al., 2003, p. 280).

Opponents of disenfranchisement of ex-felons claim that the country should follow the rule of universal suffrage for all citizens. Restrictions on voting should be enforced very carefully and only in special cases. A universal suffrage is an integral part of democracy, and it should not be violated without relevant explanations and reasons. All ex-felons are required to respect the law, pay taxes, follow the rules of the local authorities. Opponents of voting right prohibition state that it is unfair to prohibit the right to vote when the individual is expected to become a citizen who follows all obligations (Manza et al., 2003).

These points of view are taken from political debates. In addition, it is necessary to evaluate the public opinion concerning disenfranchisement. Dhami and Cruise (2013) have investigated the attitude of public towards the prohibition of the right to vote. They have found out that people favored disenfranchisement for felons who are already in prisons, serve community services, or are on parole. “It appears that people see the removal of voting rights as an additional penalty for those who have been convicted of an offence and are serving a sentence” (Dhami & Cruise, 2013, p. 222).

Taking into consideration provided facts, one may come to the conclusion that the issue may be changed with the help of advocacy. However, the public opinion may remain the same regardless of changes in the law. Social change may be required for the improvement of public opinion concerning rights of ex-felons. Addressing of the issue is crucial for the right to be called a democratic country. Also, it can contribute to the development of the better society where all people have the chance to become happy and full value citizens.

The Needed Change

Before the identification of the needed change, it is appropriate to evaluate reasons that predetermine that need and may alter the approach to change.

Political Consequences of Disenfranchisement

Eisenberg (2012) writes, “The clearest and most obvious effect — one that became very clear during the 2000 presidential election and sparked renewed scholarship on the issue — is the increasing potential for disenfranchisement laws to change the outcome of an election” (p. 547). In those years, the amount of Americans who committed felony increased — almost two million people were deprived of the right to vote. Many researchers tried to find the connection between the outcome of the election and disenfranchisement laws. Some argued that the different outcome would be possible only if all prisoners voted. Eisenberg (2012) also provides the results of the research of other sociologists who consider that disenfranchisement laws have allowed Republicans to gain the advantage in the electoral campaign.

The fairness of elections can also be argued because of the other reason. The statistical data show that most prisoners are African-Americans. In states with the most severe disenfranchisement laws (including Florida, Alabama, Maryland, and Virginia,), African-Americans comprise the majority of imprisoned population. What concerns the rest of the population, the number of black population is significantly smaller in comparison to white. Consequently, the number of African-Americans who are eligible to vote is dramatically small. It may lead to the unfair elections with the African-Americans’ opinion being neglected (Rajan, 2003). The same idea was introduced by Mauer (2002) in his study of disenfranchisement’s effects. The other opinion was presented by Miles (2004) in his empirical analysis of the impact of disenfranchisement laws on African-Americans. The author believed that the ex-felons’ prohibition to vote does not influence the outcome of the election as far as those indviduals were not likely to actively exercise this right before imprisoning.

As it has been already mentioned, the number of ex-felons increased by almost five million. This fact explains the need to allow ex-felons to vote to make results of elections fair. This change can be achieved only with the help of advocacy. Thus, it is necessary to gather information about and the impact of disenfranchisement on the electoral process.

Collateral Consequences

In some of the states, ex-convicts cannot achieve the right to vote for the rest of their lives. Such system bereaves them from the opportunity to become active members of society and leads to different long-lasting consequences.

Christian (2015) writes about labeling as the collateral consequences of being an ex-felon without the right to vote. In many cases, such experience as being in prison is not easily accepted by society. People continue looking at ex-felons like they are still guilty. The labeling theory suggests that ex-convicts feel that they cannot change. The absence of the right to vote aggravates the situation. As a result, there is a high risk of recidivism.

Recidivism is regarded as one of the most widespread collateral consequence of ex-felon disenfranchisement. As Mitchell (2004) states, “Faced with a denial of rights, ex-felons are likely to have a lack of respect for the law, and view the commission of future not as a violation of the social compact, because they are not participants in that compact” (p. 4). The deprivation of the right to vote shows ex-felon that they no longer belong to society, and they do not care about it. In such a way, a silent and invisible punishment turns out to be a significant problem of the society as a whole. Hamilton-Smith and Vogel (2012) have conducted an empirical investigation of the connection between disenfranchisement laws and recidivism in ex-felons. Recidivism is defined as the repeated commitment of crime within three years after full release from prison.

Researchers used data from the Department of Justice. In general, more than three hundred thousand prisoners from fifty states became subjects of the empirical study. The overall process of data collection lasted for fifteen years, and it was the most comprehensive records in the 1990s. The final findings of the study demonstrated that there was the connection between ex-felons’ behavior and state’s regulation of disenfranchisement. Thus, states that preferred the long-lasting prohibition of law to vote to ex-convicts experienced higher rates of recidivism among ex-felons in comparison to states with more tolerant legal practices.

Apart from labeling and recidivism issues, one more aspect of disenfranchisement has not been analyzed properly. This aspect refers to health equity. Purtle (2013) has conducted research aimed to investigate the collateral consequences of disenfranchisement from the perspective of health equity. The author employs ecosocial theory to evaluate whether there is a connection between health disparities and rights of ex-felons. Purtle has also pointed out the fact that the white population represents the majority of voters and is more likely to make decisions that are beneficial only to them. Purtle (2013) assumes, “Given the high rates of disenfranchisement in African American communities, it is plausible that disenfranchisement weakens the political influence of minority communities, thereby contributing to racial health disparities because public policy decisions do not fully reflect minority interests” (p. 634). This conclusion is logical and should be taken into account when deciding about needed changes too.

Collateral consequences demonstrate that the disenfranchisement laws have a negative influence on ex-felons and society as a whole. That is why their efficiency and implementation should be reviewed as well.

Goals

The goals are to be predetermined not only on the basis of the described needed changes. Five Core Notions of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights are taken as a cornerstone for goals and changes. These five notions include:

- Human dignity. Article 1 of Declaration states, “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood” (The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, n.d., para. 9);

- Non-discrimination that presupposes the equal treatment of all individuals regardless of race, color, sex, religion, or language;

- Civic and political rights such as freedom of thought, expression, religion, etc.;

- Economic, social, and cultural rights (rights to pleasure, employment, healthcare, food, etc.);

- Solidarity (Wronka, 2008).

Taking all of the described aspects into consideration, the following goals are to be achieved with the help of social change and advocacy:

- Restoration of voting rights for ex-felons;

- Elimination of societal resistance towards change;

- Establishment of the system of notification about possible deprivation of rights.

Analysis

The force-field analysis is to be employed to identify and briefly describe forces for and against of the needed changes.

Forces for change include substantive knowledge, political expertise, and social elements of the environment. Substantive knowledge of the issue is necessary for the understanding of major problems. Thus, substantive knowledge presupposes the existence of numerous materials and empirical studies that demonstrate the adverse effects of ex-felon disenfranchisement. All findings from studies may be concluded with the help of Sugie’s (2011) words: “A large and growing population of the politically disengaged, economically marginal, and socially excluded likely has critical repercussions for US politics, democracy, and our social contract” (p. 1).

Political expertise comprises the second force for the needed change. For example, Conn (2003) provides a detailed examination of the U.S. “partisan politics” concerning controversy about disenfranchisement laws on both state and national levels. Other similar investigation can be used as sources of political expertise that are beneficial for the accomplishment of set goals. Finally, explorations of social environment comprise the last favorable aspect for the change. Disenfranchisement laws are not positive for the society in political, social, and even health-based perspectives. These ideas have been also developed by Hull (2006).

However, several forces are against the achievement of goals. The first obstacle concerns people. As it has been showed by Manza et al. (2003), society is prejudiced when it comes to ex-felons. Such attitude may hinder the achievement of the goal. The other obstacle refers to politicians who are interested in keeping these laws. Wright (2006) has evaluated the relation between politics and voting rights and has come to the conclusion that the restoration of the voting rights is not advantageous for Democrats. The second hindrance is previous experiences. Only two states, namely Maine and Vermont, provide no restrictions for ex-felons (Policy Brief: Felony Disenfranchisement, n.d.).

Haase (2015) exhibited the difficulty by analyzing the attempts to change disenfranchisement laws in Minnesota and concluding that many efforts were made but with little progress. Other states have many rules that make it rather difficult to restore the right to vote. The last impediment is the lack of awareness of ex-felons of their rights. Some of them do not know that they can vote after prison again (Leong, n.d.).

Objectives

Set goals can be accomplished only with the help of careful and well-thought objectives. The first goal is the restoration of the voting rights of ex-felons. This target presupposes that the changes should be made in laws regulating disenfranchisement. Thus, it is necessary to provide reasons for the current laws being not appropriate. The first objective is to analyze laws and previous precedents concerning the ex-felon disenfranchisement. The aim is to demonstrate the incompetency and suggest changes to the policies.

The second goal is the elimination of the social resistance towards change. The suggestion that the society may not favor enfranchisement of ex-felons is made on the basis of previous investigations of the people’s attitude towards ex-convicts being involved in the political process. Consequently, it is necessary to report people that disenfranchisement has an adverse impact on the community as a whole. The second objective is to reveal negative consequences of ex-felon disenfranchisement for society.

The third goal recommends the creation of the system of notifications for all people who are about being (or have already been) convicted of the certain crime. This goal is predetermined by felons’ lack of knowledge of personal rights. The objective is to promote the education of felons about their rights and freedoms.

Action Plan

The first objective is to prove that the disenfranchisement laws are not competent and suggest other solutions. John Kingdon’s “policy window” theory of change (Stachowiak, 2013) will be used as a basis for advocacy. Thus, the first step is to identify the problem. Then, it is recommended to provide the proof of the statement. Finally, new policy options should be developed.

Supporters of ex-felon disenfranchisement share the opinion that ex-felons cannot be trusted because they have committed different crimes. In such a way, these proponents undermine the efficiency of the legal system of the United States of America. Criminals are convicted of the felony and are placed in correctional institutions for punishment. The task of prisons is to teach a lesson for felons. When the person has served its sentence, he or she has fulfilled its obligation. Still, supporters of disenfranchisement laws believe that ex-felons cannot be trusted, and it shows their doubts concerning the efficacy of the system of penalties of the country. As Brooks and Holmes (2004) conclude, “The logic is simple and fair: If an individual has served their time and has been determined not to be a threat to society, why should they be considered a threat to the ballot box?” (p. 17).

Disenfranchisement law has been adopted in Richardson v. Ramirez Supreme Court Decision in 1974. The decision was motivated by the Section Two of the Fourteenth Amendment, namely by the statement that individual may be deprived of the particular rights because he committed a crime that fell under the definition of the Other Crime Exception. Despite several rejections, the practice became widely used in subsequent cases (Conn, 2003). Lawyers and attorneys prove that “ex-felon disenfranchisement would be invalidated under the modern doctrine of equal voting rights under the Equal Protection Clause” (Cosgrove, 2004, p. 170). Cosgrove (2004) also evaluate other legal aspects of disenfranchisement.

These factors demonstrate the relevance of the recommendation to restore voting right for felons upon release from prison. The restoration of rights should serve as the example of entering society and becoming its member.

The second objective is to eliminate the negative attitude of society towards disenfranchisement. The Prospect Theory or “Messaging & Frameworks” theory of change will be used for this purpose (Stachowiak, 2013). This theory means that the society should be informed about negative aspects of ex-felon disenfranchisement and potential positive outcomes of the change. The successful experience of the restoration of the right to vote in Connecticut may be taken as the example. Authorities recognized the need to familiarize the community with the issue. They developed messages about the positive outcome of the policy. Those messages were spread via local media, newspapers and radio in particular. In addition, they made billboards and established campaigns that enhanced the acceptance of the change in society (Coyle, 2003).

The third objective is to promote the education of felons about their rights. Two possible ways may be used for the increasing felons’ awareness of their rights. The first is a system of notifications. Thus, upon convicted of crime commitment and sentence, felons should receive the notification about the restoration of the right to vote upon release. Rogers (2014) also adds, “Upon release, the offender should be fully informed of his rights under state law and, where appropriate, should be offered assistance in the enfranchisement process” (p. 7).

Evaluation

The evaluation of the action plan is a significant step in addressing the particular issue. The aim of the assessment is to identify potential flaws in the action plan and eliminate them. Also, the evaluation should provide some insight into the effectiveness of the action plan.

The first thing is to make sure that there are provided solutions for all goals and objectives. The need to restore voting rights of ex-felons, being the first goal, is explained in the actions plan. However, it can be rather a challenge to implement this change. The support of communities may be required. Thus, it is advisable to spread the policy plan and engage other individuals who are also concerned with this issue.

The second goal is the elimination of the society’s disapproval of the policy. The action plan presupposes the usage of media and campaigns for spreading the information about the negative impact of disenfranchisement laws on the society. The effectiveness of this objective may be checked via communication with leaders of the community where the change should be implemented. Authorities can provide additional information about peculiarities of the society and people who live there. The second goal should be effective because it is based on the evaluation of literature and pieces of research devoted to the problems of public’s attitude towards ex-felon disenfranchisement laws.

The effectiveness of the last goal is predetermined but the fact that some former felons do not know that they have the right to vote. It is estimated that the education and notification system will be useful for the formation of the feeling of belonging to society. Upon release, ex-felons will know what to do to enter society again.

Ethics and Diversity

Ex-felon disenfranchisement laws have aroused numerous discussions about ethical issues. The first ethical issue appears when it comes to the protection of rights of ex-felons. Many people who favor disenfranchisement laws argue that individuals who have committed the crime cannot be trusted anymore. It is irrational to let murderers, rapist, or thieves the right to predetermine the future and development of the country. Such considerations seem logical. However, Manza and Uggen (2006) have investigated that concern and came to the conclusion that “empirical evidence that criminal offenders would be more likely to commit electoral fraud is essentially nonexistent” (p. 13).

The democracy presupposes that all people are equal and have rights that make them a part of the society. The significance of the right to vote should not be underestimated. It belongs to the essential rights of the individual that is guaranteed by Constitution. When the person is bereaved of the right to vote, he or she experiences what is called “civic death” (Mauer, 2002). “Civic death” is a term used to describe the devastating effect on individual’s life the absence of the right to vote. Thus, it is not ethical to divest any rights upon release from prison.

Ex-felon disenfranchisement often leads to the discrimination issues. The fact is that most felons are African-Americans, and it means that many of them cannot demonstrate their interest in elections. Some scholars argue that it is a new form of racial discrimination because it is obvious that interests of African-American minorities are not represented efficiently (Mauer, 2002).

The last ethical issue refers to the discrimination of the poor. Thomson (n.d.) adds that people who experience the lack of financial resources are more likely to be sentenced and sent to prison than those who have money. Thomson (n.d.) cites the conclusion of one of the studies: “The low-income defendant [has] a greater chance than the higher-income defendant of emerging from the criminal court with an active prison sentence” (p. 9). As a result, more poor people become ex-felons who cannot vote and represent their interests. The primary aim of the action plan is directly connected to the elimination of ethical issues via the restoration of voting rights to former convicts.

Projected Results

I believe that the successful implementation of my action plan can make the life of society better. I would like to dwell on the estimated positive outcome of every goal that is defined in the action plan. The accomplishment of the first goal, the restoration of the right to vote to former felons, will reduce racial, social, and health disparities in communities. However, I understand that such positive result cannot be achieved immediately. I consider that initially it may lead to the disorientation. Proponents of ex-felon disenfranchisement will try to prove the negative consequences of the restoration of rights. In the long-term perspective, the number of individuals who are eligible to vote will increase and, consequently, they will be able to protect their interests.

The successful change in society’s attitude towards ex-felons’ rights to vote will result in the building of strong community. On the one hand, ex-felons will feel that they are full value members of society. The rate of recidivism will decrease. On the other hand, people from communities will be safe in a place with lower rates of crimes in comparison to previous years.

Reflection

In my opinion, social change, leadership, and advocacy are interconnected. I consider that advocacy and leadership are constituents of the social change to some extent. Social change presupposes that some aspects of the social life are to be modified. These changes may include people, their way of life, behaviors, relations, institutions, or activities. No change can be achieved without the leader. Although the concept of leadership may not be identified separately during the process of social change, there is no doubt that some individuals will become leaders. Leadership is crucial and unavoidable part of any change. Without the leader, any change will turn into chaos rather than an organized process. Advocacy comprises another integral constituent of the social change. It protects interests of individuals, empowers them to defend their interests and do not be afraid of changes. Thus, all three concepts are interconnected and form one unity necessary for the successful change.

My understanding of social change, leadership, and advocacy has been broadened after the preparation of the action plan addressing ex-felon disenfranchisement issues. I did not think that social change could be used for protection of the rights of convicts. The investigation of the issue made me understood that social change is much larger concept than I assumed. Also, my vision of social change and advocacy shaped my perspective on former felon disenfranchisement. I realized that all people need protection, and I felt like I could contribute to the accomplishment of important goals that would eliminate social and racial disparities.

Brief Summary of the Sources

All sources used in the current paper are peer-reviewed. The information from multiple sources was used to gather the most relevant data. Also, findings of empirical studies were utilized as well.

Rajan (2003) writes about the principle of the American democracy that can be described as “One Man, One Vote”. The author pays attentions to the fact that throughout the history, America practiced various forms of the prohibition of rights and freedoms and individuals. Although racism is believed to be overcome in the country, there are other sources of prejudices and discrimination. Ex-felon disenfranchisement laws may be called a new form of discrimination as well. Sigler (2014) describes the historical background of the problem and provides information about the current situation of disenfranchisement of ex-convicts.

The principles of the disenfranchisement laws are also described by Thompson (n.d.). Manza et al. (2003) provide readers with information about arguments for and against disenfranchisement laws. Authors use these opinions to form the overall picture of people’s attitude towards allowing ex-felons to participate in elections. Their findings demonstrate that most people are satisfied with the prohibition to vote upon the release from prison. This suggestion was supported by the other study conducted by Dhami and Cruise (2013).

Consequences of the disenfranchisement laws have been evaluated by Lynn Eisenberg (2012). The author pays attention to the fact that the prohibition to vote after prison may influence the outcomes of elections. Other collateral results of ex-felon disenfranchisement laws such as labeling, recidivism, and racial discrimination, have been identified in works of Christian (2015), Mitchel (2014), and Hamilton-Smith and Vogel (2012).

Other authors made a significant contribution by analyzing legal prerequisites for disenfranchisement laws. Thus, Cosgrove (2004) introduced the idea that these laws are no longer relevant because they do not meet the basics of modern notions of equality. Conn (2003) and Leong (n.d.) also argued the applicability of ex-felon disenfranchisement laws.

References

Brooks, T., & Holmes, B. (2004). Unlock Voting Rights: Society Suffers when Ex-Felons can’t participate. The Atlanta Journal and Constitution, 17. Web.

Christian, J. K. (2015). Re-Entering Society from Prison. Research Starters: Sociology (Online Edition). Web.

Conn, J. B. (2003). Excerpts from the Partisan Politics of Ex-Felon Disenfranchisement Laws (Doctoral Thesis, Cornell University, New York, USA). Web.

Cosgrove, J. R. (2004). Four New Arguments against the Constitutionality of Felony Disenfranchisement. Thomas Jefferson Law Review, 26(2), 158-202. Web.

Coyle, M. (2003). State-Based Advocacy on Felony Disenfranchisement. Web.

Dhami. M., & Cruise, P. (2013). Prisoners Disenfranchisement: Prisoner and Public Views of an Invisible Punishment. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 13(1), 211-227. Web.

Eisenberg, L. (2012). States as Laboratories for Federal Freedom: Case Studies in Felon Disenfranchisement Law. Legislation and public policy, 15(539), 540-581. Web.

Haase, M. (2015). Civil Death in Modern Times: Reconsidering Felony Disenfranchisement in Minnesota. Minnesota Law Review, 4(26), 1913-1933. Web.

Hamilton-Smith, G., & Vogel, M. (2012). The Violence of Voicelessness: The Impact of Felony Disenfranchisement On Recidivism. Berkeley La Raza Law Journal, 22(2), 407-431. Web.

Hull, E. (2006). Disenfranchisement of Ex-Felons. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press. Web.

Leong, N. (n.d.). Felon Reenfranchisement: Political Implications and Potential for Individual Rehabilitative Benefits. Web.

Manza, J., Brooks, C., & Uggen, C. (2003). Civil Death or Civil Rights? Public Attitudes Towards Felon Disenfranchisement in The United States. Public Opinion Quarterly, 68(2), 275-286. Web.

Manza, J., & Uggen, C. (2006). Locked Out: Felon Disenfranchisement and American Democracy. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. Web.

Mauer, M. (2002). Race, Poverty, and Felon Disenfranchisement. Poverty & Race, 11(1), 1-2. Web.

Miles, T. (2004). Felon Disenfranchisement and Voter Turnout. Journal of Legal Studies, 33(1), 85-129. Web.

Mitchell, S. (2004). The New Invisible Man: Felon Disenfranchisement Laws Harm Communities. Bad Subjects: Political Education for Everyday Life, 71(1), 1-20. Web.

Policy Brief: Felony Disenfranchisement. (n.d.). Web.

Purtle, J. (2013). Felon Disenfranchisement in the United States: A Health Equity Perspective. American Journal of Public Health, 103(4), 632-637. Web.

Rajan, S. (2003). A Modified Version of Double Jeopardy — Rehabilitated African-American Felons Barred from the Voting Box. Conference Papers — American Political Science Association, 1-27. Web.

Rogers, E. (2014). Restoring Voting Rights for Former Felons. Web.

Sigler, M. (2014). Defensible Disenfranchisement. Iowa Law Review, 99(1), 1726-1729. Web.

Stachowiak, S. (2013). Pathways for Change: 10 Theories to Inform Policy Advocacy and Policy Change Efforts. Web.

Sugie, N. (2011). Chilling Effects: The influence of partner incarceration on political participation. IDEAS Working Paper Series from RePEc, 1(1339), 1-15. Web.

The Unforgiving State. (2015). Mother Jones, 40, 26. Web.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights. (n.d.). Web.

Thomson, E. (n.d.). Felon Disenfranchisement: Why Perverts, Pedophiles, Larsonists and Arsonists Should be Allowed to Vote. Web.

Wright, J. (2006). Ex-felons still struggle to vote. Afro-American Red Star, p. 1. Web.

Wronka, J. (2008). Human Rights and Social Justice: Social action and service for the helping and health professions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Web.