The following learning activity is designed for an adult foreign language learning course, during which groups of adult learners get acquainted with a foreign language in an immersive and collaborative environment. The context for the following lesson is that the students communicate with the teacher online through Zoom and Google Docs to complete assignments and tasks both synchronously and asynchronously. In previous classes, they have learned about the present and past tense verbs and are moving on to future tense verbs. Thus, the students possess a small vocabulary and are familiar with the language enough to build simple sentences and ask questions. Based on the Understanding by Design (UbD) framework, the learning activity is created using a backward design. It starts with the evaluation of expected results, moves to methods of assessing their achievement, and ends with developing instructions and experiences (McTighe & Wiggins, 2012). The following plan presents several assignments and lesson parts that are expected to be completed in 2 hours.

First, the students are introduced to the topic of future tense verbs in several formats during an online Zoom class. The teacher begins by talking about the future, guiding the students to inquire about the related tense. A short video with text, sound, and helpful visuals explains what future tense is and how it is used in speech. Furthermore, it contains the grammatical constructions and words necessary for building sentences for talking about the future. Summaries of the video’s content and the video are made available during the lecture in the shared Google Disc folder. It is assumed that students are already familiar with the platform, as they used it several times and were coached on utilizing it at the course’s start. After reviewing the video, the teacher sends the file with the summary directly through Zoom and provides the link to it in the chat, also sharing it on the screen. Then, the instructor asks each student to build one simple sentence using a provided template with empty spaces for correct verb tenses.

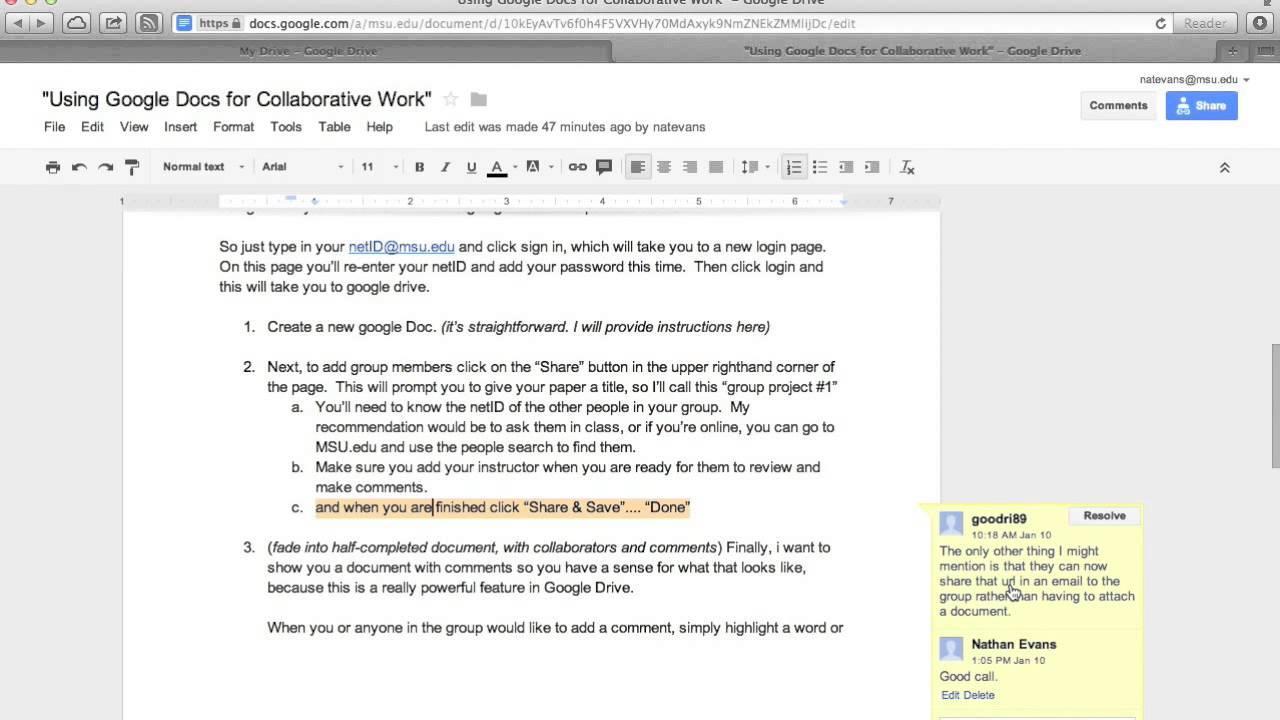

Next, the teacher separates the students into groups of 3 to 4 people and creates separate Zoom calls for each for a limited period of time. Students are instructed to write a short story, a brochure, or a dialogue using about 100 words on the topic, “What will a person do on a typical workday in 100 years?” The students will be able to share opinions using the Zoom call, Zoom chat, and a Google Docs document. An example of collaborative work on the latter platform is shown in Figure 1. The instructor visits each call for a brief period of time, reviewing the progress, answering questions, and providing assistance. Then, the students are called back into the group call to present their results by reading them together or choosing one representative.

Finally, the last part of the learning activity is asynchronous, where students are given a flexible deadline to complete. As the uploaded documents with each group’s texts are saved in the shared folder, other students can view them after the online class. Thus, each student is tasked with asking one question about one of the stories. Furthermore, each student needs to answer one of the questions asked in their story. Students who did not participate in the online part of the lesson could answer any of the questions even if another person had already answered them. The teacher engages by providing written feedback in each Google document and furthering discussion with simple questions. The main instruction is to remain topical and use future tense verbs in questions and answers. Students are given one full day to ask a question and one more day to answer one question.

Rationale and Reflection

The described above learning activity incorporates several online assignments that students can perform during and after the online lesson. As noted previously, the basis for this activity is the UbD framework which asks one to move backward when creating lessons (McTighe & Wiggins, 2012). Therefore, the lesson will be evaluated based on the principles and steps outlined in this model. The framework has three stages for creating a learning activity – the first step is to consider the goals of each exercise. The main objective of this lesson and the course is to learn the vocabulary and grammar structures of the foreign language and use them in written and spoken communication while discussing relevant and useful topics.

Next, one has to assess which tasks help reach this objective and what the students will understand after completing an exercise. It is expected that the students will be able to explain the use of future tense verbs in their own words, using examples. Furthermore, they need to apply the newly learned sentence structures and vocabulary. Explaining and applying are two of the six core facets of understanding in the UbD framework (McTighe & Wiggins, 2012). Finally, based on these aspects, one can propose assignments that target the two facets and engage students appropriately. To tackle the “explain” facet, students are provided with several types of learning material, including video, text, and conversation. This multifaceted approach is consistent with the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) guidelines. UDL principles highlight the need to “provide options for perception” and comprehension (Novak & Thibodeau, 2016, p. 22). Thus, the activity is accessible to students with various learning approaches.

Next, the writing task combines the collaborative strategy, inquiry-based learning, and accessibility. According to a study by Chu and Kennedy (2011), Google Docs is a powerful tool for collaborative learning as it has many features for synchronous and asynchronous knowledge sharing. The ability to present the text in three forms (short story, dialogue, or brochure) gives students enough freedom to choose options for “communication and expression” while focusing on writing as a vital part of language learning (Novak & Thibodeau, 2016, p. 22). Moreover, Google Docs has many features for increasing accessibility and including students with disabilities and different learning strategies in the collaboration (Coffman, 2017). For example, it is compatible with many text-to-speech and text recognition applications. The service also has a built-in translator and a magnifier and allows to format texts to enhance visibility and readability.

Inquiry-based learning for this assignment is caused by the absence of the teacher’s control during the text creation. The students are provided with basic instructions and a question that leads to discussion. Thus, it is expected that the learners will enter an investigation phase, during which they will search for ideas and appropriate words and phrases to express them (Coffman, 2017). Through planning and experimentation, they will create a text that incorporates their group exploration and knowledge sharing. During this assignment, the instructor monitors groups briefly to provide resources if necessary or provide feedback to further the discussion, thus allowing students to tackle the task through peer support.

The presentation of the created collaborative work tests learners’ speaking skills while also giving them an opportunity to avoid speaking if they experience technical or other problems at the moment. It should be noted that the instructor should remember which students are talking more than others to work with the non-speaking students during the following lessons and assignments. This part of the assignment furthers collaboration and active listening among learners from other groups, as they are encouraged to ask questions and react to the story during and after the lesson. The final part of the assignment does not provide much freedom in choosing the medium. However, it is asynchronous to give students time to prepare their questions and answer in a way that suits them. Furthermore, it is short enough not to raise any barriers while strengthening student participation and collaboration outside synchronous lessons.

Adult learning experiences differ from those of children and teenagers due to their different priorities and learning goals. Adults learn when they are motivated by their personal objectives that they want to reach by acquiring specific skills and knowledge (Knowles et al., 2005). Therefore, focusing on information relevant to the learners’ interests is vital. In the case of language learning, verb tenses are necessary for daily conversations, and the topic of work and schedules is an integral part of most adults’ routines. Thus, the students are expected to be engaged in the assignments and contribute to them. Moreover, the topic chosen for the written task fosters creativity and imagination, which allows for wider use of vocabulary, providing adults with an opportunity to create fantastical or serious texts. Access to the internet gives the learners a chance to learn new words while applying the already learned sentence structure and verbs. Creativity increases students’ engagement and raises the possibility of a positive outcome and goal achievement (Hess, 2020). Thus, adult learning has to encourage creativity and focus on relevant information to reach success.

Moreover, online learning poses several challenges and limitations for activity development and implementation. First, not all students can participate in synchronous activities, which may make them feel discouraged or excluded from the course (Azionya & Nhedzi, 2021). To combat this, the current activity plan includes several ways of accessing information and post-lesson exercises to ensure participation and learning. Students who missed the lesson can still download and access all course materials. Moreover, they are encouraged to ask questions about others’ stories and answer questions from other learners. These tasks include students and test their knowledge regardless of whether the individuals were present during other assignments.

Second, learners with disabilities cannot always participate in activities, especially if the chosen method of information sharing and communication is not equipped with accessibility features. The choice of Zoom and Google Docs combination is meant to help overcome this issue. First, the two applications allow one to answer with voice or text, assisting deaf and blind students. As mentioned above, Google Docs supports voice-to-text and screen reader software (Google Docs Editors Help, 2022). Moreover, it has a screen magnifier and formatting features to help people with dyslexia and vision impairments. Multiple means of action are vital for ensuring accessible learning (Novak & Thibodeau, 2016). The selected tools increase the chance that students will be able to participate in a lesson in one way or another. Overall, the activity incorporates several aspects of accessibility, collaboration, and inquiry to increase the participation of adult learners and keep them engaged.

References

Azionya, C. M., & Nhedzi, A. (2021). The digital divide and higher education challenge with emergency online learning: Analysis of tweets in the wake of the Covid-19 lockdown. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 22(4), 164-182.

Chu, S. K. W., & Kennedy, D. M. (2011). Using online collaborative tools for groups to co‐construct knowledge. Online Information Review, 35(4), 581-597.

Coffman, T. (2017). Inquiry-based learning: Designing instruction to promote higher level thinking (3rd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield.

Google Docs Editors Help. (2022). Accessibility for Google Docs, Sheets, Slides, & Drawings. Web.

Hess, A., N. (2020). Modular online learning design: A flexible approach for diverse learning needs. American Library Association.

Knowles, M. S., Holton III, E. F., & Swanson, R. A. (2005). The adult learner: The definitive classic in adult education and human resource development. Taylor & Francis Group.

McTighe, J. & Wiggins, G. (2012). Understanding by Design® framework. ASCD.

MSU Information Technology Academic Technology. (2013). Using Google Docs for collaborative work [Video]. YouTube. Web.

Novak, K., & Thibodeau, T. (2016). UDL in the cloud: How to design and deliver online education using Universal Design for Learning. CAST Professional Publishing.