The power of advertising has often been underestimated in society because of the limited understanding of its effects on human behavior. However, the definition, role, and perceived value of “femininity” in society are constantly influencing how advertisements are designed today. Indeed, equality is constantly assuming new definitions because more advertisements are focusing on the equality of men and women in society. Therefore, women can pursue their career goals in a world that is more tolerant of gender differences. Nonetheless, the advertisement landscape today is still male-dominated and has a lot of opportunities for advertisers who are willing to tap into this culture.

For example, a recent collaboration between Unilever and Kantar Watson revealed that advertisements showing progressive male images are more impactful than those that do not. However, as Bob Liodice, CEO of the National Association of Advertisers (ANA) once said, “The right advertising environment for women can improve ad effectiveness by as much as 30%” (Neff 2016, para. 13). However, the convergence of “traditional” gender roles and the emergence of more progressive ideas about sexuality have made the situation more complicated (Fridlund 2017; Kilbourne 2000). This paper is a literature review of articles that have focused on explaining the evolution of advertising through the sexualization of the media and technological progress. However, before reviewing the literature, it is vital to understand how women are portrayed in advertisements.

Review

Objectification of Women in Advertisements

The sexualization of women in advertisements comes from a larger trend of making advertisements appealing and entertaining. From a technical point of view, sexually suggestive ads are so popular that they are supported by some advertising theories and models, such as the three principles of advertising creativity: fear, humor, and sex appeal (Unnithan 2018). The sexual appeal of advertisements is also explained by the three B principles of advertising performance: beauty, baby, and beast or beauties, children, and animals. Studies that have assessed these items of analysis rank sexy carrier beauty or the sex appeal of products before all others (Unnithan 2018).

In the early 1970s, British cultural critic Berger et al. (1972) put forward in the book “Ways of Seeing”, collecting oil paintings and viewing oil paintings, how men have strong desires to possess objects. The problem of the “male gaze” in the aesthetic tradition, as proposed by Berger et al. (1972) had an important influence on the analysis of feminist views about the female body. Based on this review, the relationship between viewing and possession became another item for analyzing gender images in advertising. Therefore, the problems associated with the sexualization of women can be compared to debates surrounding oil paintings, which are completed by men to depict women’s nudity.

For example, in the centuries of European painting tradition, male audiences often consumed male-created content depicting nude female bodies (Unnithan 2018). This practice is also evident in modern advertising because goods that are targeting men contain women’s images as an object of persuasion. This advertisement strategy has been applied to several products. For example, most traditional advertisements involving females but targeted men had a large number of female workers (Fridlund 2017). In line with this view, the images of ships, houses, and riders that appeared in past cigarette advertisements, such as that of Marlboro, represented objects of male desire. The target market was equally male because advertisers hoped to attract seafarers, craftsmen, and athletes. The images of children and women in the cigarette posters and advertisements were just “bait” for tobacco companies to persuade men to buy their products. Therefore, advertising uses consumers’ love of female images to create brands and promote products.

According to Fridlund (2019), a broad overview of the use of women and sexuality in advertisements suggest that there are three stages of ‘sexual’ advertisement from the past to the present. The first one represents traditional advertisements, where women rarely appeared in advertisements, and those that did, had low-status roles, such as a washer, cleaner, or nanny (Fridlund 2017). In the second stage of sexual advertisement, people tried to express gender differences and the conflict between men and women (Dittrich 1994). Particularly, they strengthened the dominant position of men in society and ignored the subjectivity of female roles or indirectly supported their conception as sexual objects.

Relative to this assertion, Anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss (1969) found that human societies have three cultural exchange processes: information, women, and goods. To promote the commercial appeal of products and maximize financial interests, women are often materialized and become commoditized for commercial appeal. In some advertisements, they appear as decorative objects, whereby they are placed next to a product, even though they may have no substantial relationship with the product function. In this regard, women influence the value of commodities by accepting to take part in the advertisement process to fulfill this role. For example, most advertisements match women with goods, implying that both of them are equivalent to each other, are possessions of men, and represent symbols of status upgrades.

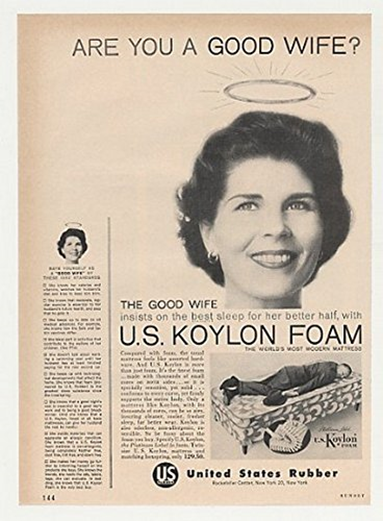

Comparatively, emerging forces are trying to question the sexualization of women in the advertisement. For example, the publication of Betty Friedan’s “The Feminine Mystique” in 1963 started a wave of women’s liberation movement. In line with this trend, advertisements showing the rigid or traditional view of women as sex objects were rebuked. Companies are also following the trend, as can be seen by the improved use of women in cigarette advertisements. In addition, under Friedan’s influence, the National Women’s Organization and other female-based groups in the United States have criticized the sexualization of women in advertisements. This criticism has been highlighted in several advertisements, such as the one highlighted in figure 1 below.

As highlighted above, the ad contains the image of a woman smiling and another one where a man is sleeping comfortably on a bed. The title of the advertisement is: “Are you a good wife?” meaning that the better half of her has the best sleep because it uses a Koylon foam mattress (Jones & Reida 2009). This kind of prejudice promotes the sexualization of women in marketing. To illustrate this point, it is important to analyze the advertisement of car seat belts because even though they are deemed safer than not having one at all, most crash tests have used male-modeled dummies. Alternatively, in June 2016, Unilever started a company-wide initiative dubbed “Unstereotype Alliance” to re-examine the company’s description of women in advertising campaigns and work to present a more aggressive female identity, image, and vision of future marketing communications (Ads Past 2019). This movement encourages the whole industry to improve the equality of men and women.

For example, one World Cup advertisement contained a quote that said, “We don’t have balls. But we know how to use them” (Beer 2019, para. 1). This statement highlights the reengineering of sexual roles to have more impact on audiences. As part of critical consciousness to promote equality, the highest ideal type provided by gender-based advertisements is pluralism, which discards the concept of gender and replaces it with a more fluid identity of men and women as individuals rather than groups. At this level of assessment, society accommodates individuals with different biological makeups, gender traits, or sexual orientations, and individuals no longer have to live to fulfill their traditional male and female roles. Therefore advertising sexualized images at this level of perception reflects diversity because there are rich and diverse men or women with physical and sexual characteristics, personality types, abilities, professional roles, and family ties that make it essential to go beyond gender role stereotypes in advertisements and give audiences more choices. In this sense, advertising is no longer one type of media content that reinforces traditional gender construction (or sexism).

Journals and Books Reviewed

Gunter (2014) talks about the role of the media in promoting a sexualized agenda of childhood advertising. Although the sexualization of children is largely seen as a negative attribute, Gunter (2014) invites readers to think of the process positively by suggesting that children who have been exposed to sexualized advertisements will stay ahead of the rest. Relative to this assertion, the author says, “IT will still be the young digital natives brought up with this evolving world of rapidly changing computer technology who will stay ahead of the rest – as it has always been in the past” (Gunter 2014, p. 211). Broadly, the information contained in this book helps to explain the origins of female sexualization in modern advertisements and examines how new advertisements could be changed based on the same nuances.

In their book, Reichert and Lambiase (2014) discuss the role of sex in advertisements by suggesting that it creates an erotic appeal to consumers, which enables brands to develop effective and memorable messages for their products or services. The book also talks about the role of technology in distributing these messages with a keen focus on how men have shaped public discourse in this regard. For example, the authors say that “technology itself is gendered” (Reichert & Lambiase 2014, p. 262). This statement was made to suggest that technology has “male creators” who control it. The pieces of information contained in this book are useful in understanding how women are used in advertisements to make effective brand imaging using technology as a tool.

In his book, Berger (2008) discusses how consumers view art. Particularly, it talks about the power of perception in influencing people’s buying choices. To demonstrate this point, the researcher referred to the “sexualization” of women in advertisements by saying, “You painted a naked woman because you enjoyed looking at her, put a mirror in her hand and you called the painting Vanity, thus morally condemning the woman whose nakedness you had depicted for you to own pleasure” (Berger 2008, p. 29). This statement talks about how different perceptions of branding could be developed from the same object or premise of discussion. Overall, the book is relevant in informing consumers’ understanding of market effectiveness in today’s globalized world because it helps to explain how technology can create alternate views about products and services by influencing people’s perceptions of them.

In his book, Williamson (1991) discusses how people interpret advertisements by examining psychological links in messaging. Relative to this view, the author says, “Advertising seems to have a life of its own, it exists in and out of other media, and speaks to us in a language we can recognise but a voice we can never identify” (Williamson 1991, p. 14). This statement is a powerful reminder of the role consumers play in giving advertisements an identity or impetus to influence consumer behavior. Overall, the book is useful in understanding how sexuality and gender have evolved in an era characterized by increased consumer power because of technology’s pervasiveness.

Klein (2009) highlights the role of powerful branding in today’s modern world and how there is a movement to resist it through self-determination and personal branding. To affirm this position, the author says, “What haunts me is not exactly the absence of literal space so much as a deep craving for metaphorical space: release, escape, some kind of open-ended freedom” (p. 56). The freedom referred to in the text is largely offered through various technological platforms, including social media. The findings of this study are useful in understanding the role of technology in advertisements because the platform gives people an opportunity to control public discourse away from traditional brands and companies.

Osborne and Coombs (2015) highlight the sexualization of women in advertisements using the National Football League (NFL) as an example. The researchers suggest that although people may find the use of “sex” to sell products as an objectification of women, few find it offensive. Relative to this observation, the author says, “Young women, it appears, have grown to expect sexualised images in advertising and, likely, even fail to pay attention to them” (Osborne & Coombs 2015, p. 182). This book does not closely focus on the role of technology in shaping advertisements but highlights the attitudes women and the public have towards their objectification. The findings also show that people have generally become insensitive to such prejudices and companies are benefitting from the situation because nobody seems to care.

Walters (2014) discusses the role of the media in shaping popular culture and advertisements. Particularly, the role of changing media is highlighted as one of the most powerful forces shaping public opinions about different products and services. Relative to this statement, Walters (2014, p. 81 ) says “Over the last two decades, perhaps as a response to these changes, the media has valorised traditional second homes, and the ‘bach’ has been increasingly constructed as a form of ‘cultural icon.” This statement was made about advertisements in the real estate sector but they are useful to branding in general because they highlight the role of technology in shaping people’s opinions about products and services.

Andersen, Taylor, and Logio (2014) reinforce the views highlighted above (about women in advertisements) but take a sociocultural approach in investigating the insensitivity of modern advertisements towards the objectivity of women. It suggests that such practices are deeply embedded in traditional patriarchal norms of various religions. The authors use this explanation to say that “women are more likely now to be portrayed as employed outside of the home and in professional jobs, but it is still more usual to see them depicted as sex objects” (Andersen, Taylor & Logio 2014, p. 262). This book is useful in linking traditional advertisement practices and modern nuances on branding to have a broader understanding of why the sexualization of women in advertising is pervasive.

Greenwood and Dwyer (2014) draw attention to the challenges of information complexity in engaging the advertisement industry. The authors say that “Information complexity can sometimes be reduced by drawing on the experience of more knowledgeable friends and relatives (word of mouth), by access to internet sites” (Greenwood & Dwyer 2014, p. 5). This statement highlights the role of technology as a tool for helping researchers assess market information.

Robbins (2014) highlights the role of body image in advertisements as a source of pride and shame for women. The analysis mostly relates to how some women have been made to feel “unworthy” because their body images do not conform to the mainstream perception of “perfect bodies.” Nonetheless, Robbins (2014, p. 111) recognizes the intertwined nature of gender roles with society’s constructs of masculinity and feminism when he suggested that, “future research investigating body image may also need to include the role of sociocultural factors, as well as personality disposition and gender role orientation in analysing markets.” Relative to this statement, this article is relevant to understanding how advertisements are designed because they tap into the role of body image in shaping the psychological processes affecting buying behaviors.

Angell et al. (2016) explained the role of technology in creating multiple gadgets for consumers to decipher the information. The multiplicity of technological devices has made it possible for customers to multitask but doing so has harmed their memory. Relative to this assertion the authors suggest that “when motivation is high, memory for advertising delivered via the medium of the primary activity, will be better recalled and recognised” (Angell et al. 2016, p. 20). The findings of this paper are useful in understanding the attitudes consumers hold about brands and their intentions to purchase products and services.

Phippen (2018) highlights the role of technology in shaping gender identities in advertisements. Particularly, the researcher draws attention to how personal advertisements have been changing via social media and how women are being sexualized through changes in communication behaviors, such as “sexting.” Relative to this statement, the researcher said, “The issue of self-generated images being shared through sexting has been overtaken by girls posting pictures of themselves on social media wearing little or no clothes, citing the media as an influence…” (Phippen 2018, p. 1). The findings of this study would be useful in understanding how consumers use technological platforms to make purchasing decisions. They are also vital in understanding consumer trends and how brands can leverage the same to increase their profitability.

Unnithan (2018) explains what it means to be an ideal woman by examining gender roles in advertising. The findings suggest that stereotypical roles of women in advertising come from different intrinsic and extrinsic factors that shape a woman’s life from birth. Consequently, Unnithan (2018, p. 33) says, “Efforts to adhere to the ideal woman benchmark are reflected in women’s consumption.” The findings of this article are useful in understanding why there is an overemphasis on gender stereotyping in marketing.

Rocha and Frid (2018) investigated why companies use attractive images of women in Brazilian magazines. In line with this discussion, the authors argue that “the existence and operation of an underlying recurrent pattern that intends to classify products and services according to female body fragments is a process analogous to the system known as totemism” (Rocha & Frid 2018, p. 83). In other words, the sexualization of women in advertisements comes from a mysterious relationship that human beings have with a spiritual being, which is hereby represented as a woman. The findings of this study are instrumental in understanding the fascination with women’s bodies in advertisements.

Cummings (2018) underscores the relationship between representations of white male masculinity, modern advertisements, and technology. Using advertisements on Twitter as a case study, the article suggests that “cultural representations are reflective of Twitter’s specificities as a social media platform, and second, that these representations work in conjunction with cultural norms of the contemporary US” (p. 1). The findings of this study are useful in understanding the relationship between gender stereotypes, technology, and the present socio-cultural environment of the global society.

3.0 Summary

The notes highlighted in this paper show that gender roles and technology are intertwined to the extent that existing stereotypes about sexism (in advertisements) represent human prejudices about gender roles in society. Comparatively, technology is presented as a platform through which such prejudices are expressed. However, the articles and books sampled in this review are only indicative of the extent that companies use gender and technology to create effective advertisements. A deeper interrogation of their findings is essential in improving current discourse on the subject.

Reference List

Andersen, ML, Taylor, HF & Logio, KA 2014, Sociology: the essentials, Cengage Learning, London.

Angell, R, Gorton, M, Sauer, J, Bottomley, P & White, J 2016, ‘Don’t distract me when I’m media multitasking: towards a theory for raising advertising recall and recognition’, Journal of Advertising, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 198-210.

Beer, J 2019, This World Cup ad for Germany’s women’s soccer team brilliantly addresses gender inequality in sports, Web.

Berger, J, Blomberg, S, Fox, C, Dibb, M & Hollis, R 1972, Ways of seeing, Penguin, London.

Berger, J 2008, Ways of seeing, Penguin Books Limited, New York, NY.

Cummings, K 2018, ‘Life savers: technology and white masculinities in Twitter-based superhero film promotion’, Social Media and Society, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 1-10.

Dittrich, L 1994, About-face facts on the MEDIA, The Commercial Press, New York, NY.

Fridlund, A 2017, Gender differentiated design: does your brand do it, Web.

Fridlund, A 2019,Gender intelligent design: what brands, product designers and customer services need to know, Web.

Greenwood, V & Dwyer, L 2014, ‘Challenges to consumer protection legislation in tourism contexts’, Journal of Tourism Consumption and Practice, vol. 6, no. 2, pp.1-22.

Gunter, B 2014, Media and the sexualization of childhood, Routledge, London.

Jones, S & Reid, A 2009, ‘The use of female sexuality in Australian alcohol advertising: public policy implications of young adults’ reactions to stereotypes’, Journal of Public Affairs, vol. 10, no. 1, pp.19-35.

Kilbourne, J 2000, Deadly persuasion, Simon & Schuster, New York, NY.

Klein, N 2009, No logo: no space, no choice, no jobs, 3rd edn, Picador, London.

Lévi-Strauss, C 1969, The elementary structures of kinship, Beacon Press, Boston, MA.

Osborne, AC & Coombs, DS 2015, Female fans of the NFL: taking their place in the stands, Routledge, London.

Neff, J 2016, ANA moves to eliminate bias against women from ads and media, Web.

Phippen, AD 2018, ‘Sexting and sexting behaviour – oh you’re all children, children do silly things. You’ll be fine. Get over it!’, Entertainment Law Review, vol. 28, no. 6, pp. 1-10.

Reichert, T & Lambiase, J (eds) 2014, Sex in advertising: perspectives on the erotic appeal, Routledge, London.

Robbins, A 2014, ‘The interplay of gender role orientation and type-D personality as predictors of body dissatisfaction in undergraduate women’, The Plymouth Student Scientist, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 101-117.

Rocha, E & Frid, M 2018, ‘Classified beauty: goods and bodies in Brazilian women’s magazines’, Journal of Consumer Culture, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 83-102.

Unnithan, AB 2018, ‘Self and identity of being an ideal woman: an exploratory qualitative study’, IIM Kozhikode Society & Management Review, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 33-44.

Walters, T 2014, ‘Cultural icons: media representations of second homes in New Zealand’, Journal of Tourism Consumption and Practice, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 81-103.

Williamson, J 1991, Decoding advertisements: ideology and meaning in advertising, Boyars, London.