Waste Water Treatment Plants (WWTP) in the GCC (Gulf Cooperation Council) region were built to meet the ever-increasing demand due to population growth in the region. This was projected to be a cost-effective venture that would be environmentally friendly and vital in reducing carbon emissions (Al Mazroui, 2000).

The first WWTP to be launched in Abu Dhabi, the second-largest city in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), was done in 1973. This was designed to recycle 4,545 cubic meters of wastewater daily (Vesela, 2007). Nonetheless, with the increasing demand owing to a growing population, the Sewerage Project Committee commissioned the development of another unit with a bigger capacity to meet the water demand. According to the planners, the unit was to be constructed in Al Mafraq, an Abu Dhabi hinterland 40 KM away and 40 meters above sea level (Redouane, 2010). This was designed to treat a volume of approximately 100,000 cubic meters of wastewater per day, serving a population of nearly 332,500 people. However, with the growing pressure due to population increase, this plant was upgraded in 1997 to accommodate a volume of nearly 260,625 cubic meters per day. Furthermore, the Water Research Company (WRC) increased its efficiency to accommodate a capacity of approximately 320,000m3/day. With this capacity, the plant was projected to serve a population of 0.9 million.

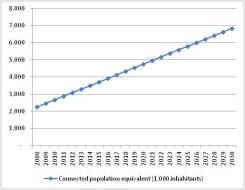

Of note, since the year 1999, the plant has continuously been upgraded. As such, before the year 2001, the initial phase was rehabilitated, and in the year 2003, the management took the initiative to engage in the environmental management of both biosolids and odor. Despite the efforts geared towards increasing the capacity of Mafraq WWTP, the plant’s capacity has continuously been overstretched owing to a higher population growth rate (Fig. 1) that is synonymous with this realm.

With the above projection, the ADSSC (Abu Dhabi Sewerage Services Company) has braced itself to meeting the future demand (Dawoud, 2005). As such, the projects for the construction of WWTPs in Abu Dhabi have been given a priority, becoming part of the state’s vision 2030. The initial plan was meant to build four plants by the year 2013. This was envisioned to increase the overall capacity of recycled water to 850,000 cm3 per day, meant to serve a population of approximately 3 million people. These plants, which form part of the two major projects, are located in Wathba. Once completed, the plants will ease Mafraq WWTP from its current pressure of recycling wastewater that is beyond its designated capacity.

To date, Mafraq WWTP has had to recycle wastewater that is way beyond its capacity following an increased water demand. This has impacted negatively to the environment, prompting the stakeholders to raise an alarm over the same. The problem of wastewater overload in Mafraq WWTP stretches way back beyond the year 2005. Over the years, Mafraq WWTP has had to cope with the overload. The trend of capacity between the years 2005 and 2006 before the plant was upgraded is as shown in the figure below. Basically, as of the year 2006, Mafraq was accounting for 95% of the total wastewater treatment in the UAE.

According to environmentalists, this plant was on the verge of collapsing had it not been upgraded. The amount of sludge generated during this period was overwhelming the plant’s capacity (see Fig. 3 below) (Hyder Consulting, 2002).

Since Mafraq WWTP accounts for a bigger percentage of the wastewater treatment plants in Abu Dhabi, its trend portraying an overload of wastewater (fig. 2) has been replicated in the national arena from the years 2006 to 2010 (fig. 5) (ICBA Report, 2004). According to the ADSSC annual report, over the years, the plant has been incurring high operation costs in water collection activities (over 8 billion AED in 2010). The opposite is true when it comes to the operation cost of wastewater disposal activities (less than 50 million AED in 2010). The treatment costs are fairly constant at below 150 million AED (fig. 6). Overall, the total operating costs have continued to soar with increasing demand. The capital costs follow the same trend, however; recently, the capital cost incurred in wastewater disposal has surpassed the treatment capital costs (fig. 7). Comparatively, the capital cost surpasses the operation costs. A financial report released by ADSSC in the year 2010 shows that the WWTPs are operating at a loss. This trend can, however, be reversed with proper management of both the assets and the human resource (ADSSC Annual Report, 2010).

The cost of wastewater treatment averages at a value of AED 1.52 per cubic metre across all the WWTPs. With this, the consumer’s purchase prizes range between AED 2-3 m-3.

References

ADSSC Annual Report. (2010). ADSSC Mafraq wastewater treatment plant. New York: Dover.

Al Houqani, H. (2005). An ArcGIS Database for Water Resources Management in Abu Dhabi Emirate, United Arab Emirates. In Proceedings of seventh Gulf Water Conference, Kuwait, 5 (1): 3-8.

Al Mazroui, F. (2000). Abu Dhabi Initiative s in re-using its effluent. In Proceedings of Aqu Abu Dhabi, 2000, Wastewater Management for a better environment, 4 (3), 9-10.

Al wathba Veolia Besix Waste Water. (2010). Water Conservation in Abu Dhabi. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Dawoud, M. (2005). The Effect of Water Scarcity on the Future Growth in the Desalination Industry in GCC Countries. Water – Resources, Technologies and Management in the Arab World. Abu Dhabi: University of Sharjah Press.

Hyder Consulting. ( 2002). The Study of Treated Sewage Effluent Transmission and Distribution System and Irrigation Management – Abu Dhabi Municipality Sewerage Projects Committee. Abu Dhabi: Arabian peninsula Press.

ICBA Report. (2004). PMS32Feasibility study for biosaline agriculture in the United Arab Emirates. Abu Dhabi: University of Sharjah Press.

Redouane, C. (2010). Regional Experience of Wastewater Treatment and Reuse in the Arab countries. Abu Dhabi: University of Sharjah Press.

Vesela, T. (2007). New sewage plants to play double role. The National. 2010 Abu Dhabi WWTPs have the EUCH factor. Global Water Intelligence, 8 (6), 3-7.