Artist’s Work and Ideas

Albert Namatjira was born on July 28, 1902, in the heart of Australia, not far from Alice Springs, where his native Aranda tribe roamed from time immemorial. At birth, he received the pagan name Elea (Williams, 2007). Nearby was the Lutheran mission of Hermannsburg, where the tribespeople of Namatjira often visited to earn extra money and, at the same time, listen to the priests’ sermons. The father of the future artist imbued with the ideas of Christianity, baptized his son (Wall, 2022). At baptism, he was named Albert, but when the boy was 13 years old, he passed the rite of initiation into men or initiation according to the customs of his tribe and became a full member of it.

Soon, however, Namatjira broke the laws of the tribe by marrying a woman from another tribe named Ilikalita. The artist was engaged in producing traditional drawings – animals and hunting scenes (Aitken & Wareham, 2017). However, he did not achieve success in this field. These were ordinary crafts akin to rock carvings. At the time, Rex Batterby, an artist from Melbourne, came to Hermannsburg, decided to paint a series of local landscapes, and hired Albert as a guide (Giffard-Foret, 2018). Albert watched with interest how the artist worked. One day he asked him for a brush, paper, and watercolors and confidently painted a landscape in the style of Batterby.

In 1938, in Melbourne, the first exhibition of Namatjira was held with great success. Over the next ten years, Namatjira worked hard, and his fame spread far beyond Australia: he was talked about in England and America (McLean, 2018). The world has not forgotten about the original Australian, who, with his work, proved the inconsistency of the racist theory about the inferiority of some people. His work can be seen in major museums around the world. His work became an example for many talented natives who followed in the footsteps of their famous fellow citizens. Albert’s sons also became artists; they continued the traditions of their father.

Namatjira began to paint in a unique style. His landscapes typically emphasized the rugged geological features of the land in the background and the distinctive Australian flora in the foreground with ancient, majestic, and majestic white gum trees surrounded by twisted shrubbery (Wall, 2022). His work had a high quality of lighting, showing the irregular patches of land and the curves of the trees. His colors were similar to the ochres his ancestors used to depict the same landscape, but Europeans appreciated his style because it matched the aesthetics of Western art.

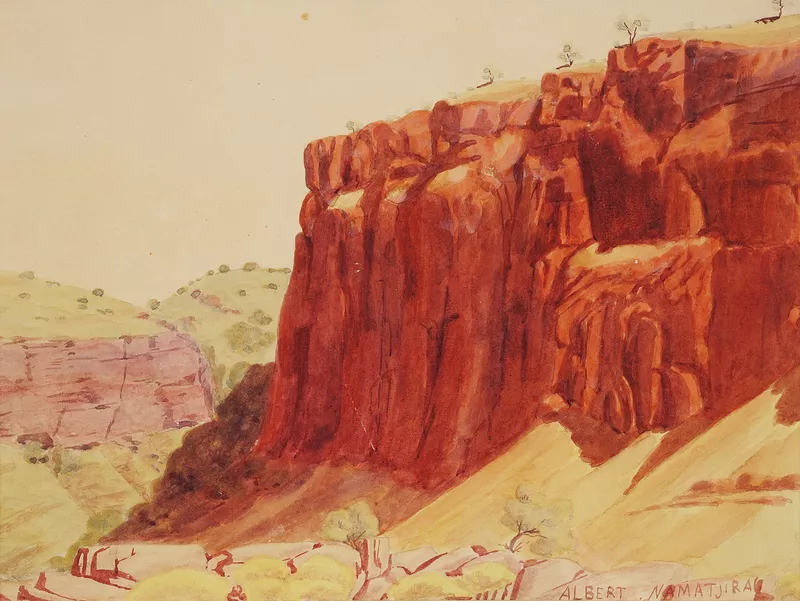

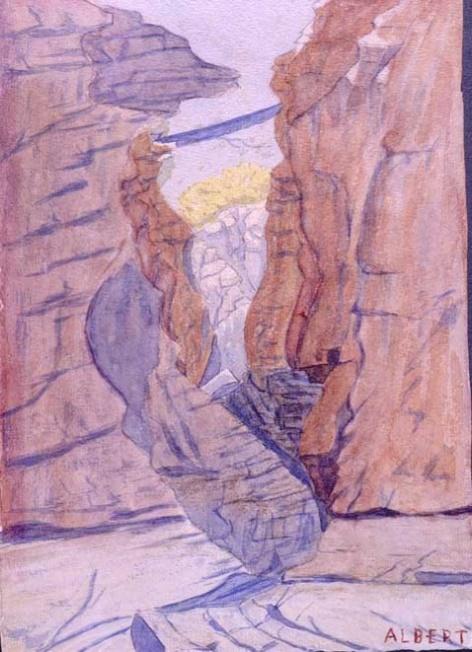

Early in his career, Namatjir’s work included drawings of sacred objects, biblical themes, and symbolic objects, and he carved and painted various artifacts. The artworks were colorful and varied depictions of the Australian landscape. One of his first landscapes from 1936, Landscape of Central Australia in Figure 1, depicts a country of green hills (Namatjira, 1936). Another early work in Figure 2, Waterhole Ajantzi from 1937, shows a close-up view of a small watering hole in which Namatjira captured the reflection in the water (Namatjira, 1937). We can assume that this artist captured in his paintings not only the beautiful landscapes of his native area but also filled them with his deeds with sharp meanings on the rights of the natives. Heartfelt for his lands, Namatjira invested in his work something more than a colorful representation of remote places on the earth, which allows touching the study of his paintings in more detail.

Teaching Methods and Activities

All children strive to learn about the world around them and are fond of various processes. They are interested in many things and learn new skills easily and quickly. That is why it is helpful at an early age to cultivate a sense of aesthetics in a person to develop creative inclinations. Painting for children is perhaps best suited for these tasks. In this regard, it is proposed to enter information and works of this artist to students of the second stage, aged from seven to eleven years. Painting classes develop taste and develop imagination (Probosiwi & Hastuti, 2019). They teach to notice the beauty around them, recreate it through fine art, and express their ideas and fantasies on paper in the form of visual images. It does not matter that children’s drawings are much less accurate and realistic than the work of adult artists. The main thing is that the child gradually learns to speak the language of art.

The example of Namatjira is clear enough from the point of view of his work. Children of this age can easily perceive landscapes with familiar elements while discovering new settings (Probosiwi & Hastuti, 2019). Flora and fauna of Australia are pretty unique, in connection with which the curiosity functional is manifested and various questions and interests are stimulated (Gurr, 2020). The artist’s style is maintained throughout his work, making it easier for young children to perceive his work for the most part. Consequently, children begin to get acquainted with the technique of performing work, just as Namatjira once moved from rock paintings to landscapes, and study the world around him.

Accordingly, the chosen methods involve acquaintance with the artist and his works at the initial stage. The traditional art of the Aranda tribe has pictorial elements but cannot be called a painting. It was a syncretic verbal and visual art in which the image was explained by speech and the image concretized speech. Aborigines, telling something, drew circles, semicircles, spirals, and straight and curved lines on wooden shields, sacred objects, and the sand, each of which has its meaning. In fact, creativity was on the border of the writing of the language and painting, with which Namatjira began and with which the curriculum of children began. Such a transition to classical painting with a recognizable touch is a logical and recognizable approach in education that children will understand at a logical level, which only confirms the need to get to know the artist at this stage.

The Australian region’s remoteness and uniqueness attract children’s attention, given the color schemes in the artist’s paintings. At the moment, many may not be geographically familiar in such detail about the structure of the world and the existence of this continent as a whole, which creates fertile ground for new knowledge. Children open up to explore new regions by meeting someone who puts true love into the depicted landscapes through the severe pain of harsh reality in the struggle for their rights. However, the negative side of his biography can be saved for a later acquaintance, when students will already be able to demonstrate critical thinking skills and study more complex social and political interaction structures. In this case, a delayed image of the artist is formed, which first reveals itself as a talented creator in students’ childhood and then as a person in a more mature sense.

Acquaintance with the works of the artist can take place in various forms: from a classical exhibition to a play. For example, it is possible to present the work in the form of puzzles to engage children’s fine motor skills and add a competitive element to the lesson. Artistic elements without proper accompaniment can be boring for a child who would instead find something else to do. In this regard, in the methodology, it is essential to accompany acquaintance with creativity with certain games, sketches, listening to music, and an attempt by children to try their hand at creativity. For example, each class can choose any picture from the impromptu exhibition and try to depict it using the necessary drawing tools or choose their own. The fewer restrictions at this stage, the more creativity can be nurtured in students within the framework of the work program.

The uniqueness of Albert Namatjira’s works also lies in their involvement in the ancient foundations of the aboriginal world, which is extremely far from modern man, and can be incredibly interesting for children. Totem art, isolation from civilization, and many of the most important rituals in the life of every aboriginal, supported by the entire community – all these events have an imprint on a person and his paintings and can tell a lot to modern children.

Thus, it is possible to acquaint students with history if they are invited to perform any ritual from the antiquity of the aborigines in a playful way, presenting the artist’s paintings as the surrounding landscape. At the same time, Namatjira’s work remained non-politicized, despite his active civic position. The example of the artist is also highly indicative from the point of view of the values brought up in children: he remained a man and used fame and improvement in his financial situation as an opportunity to help his settlement, relatives, acquaintances, and even unfamiliar natives.

Diverse Learners

In this way, children are exposed to inclusiveness and diversity. These critical values are vital goals in the school’s educational function (Sanchez et al., 2018). Embracing a different culture through similar stories and a person’s creativity from the other side of the world can contribute to a healthier classroom atmosphere. Considering that diverse learners should be considered, such practice should be carried out relatively often and in an accessible, playful, and easy way for children in the second stage. For example, if there are students with disabilities in the team, then it is necessary to highlight a course of activities that would help, by their capabilities, to involve them in everyday activities within the lesson. If the student has difficulty moving, then putting the puzzles into pictures with further conversation and discussion of the story may better develop a sense of diversity and inclusion among other students and a sense of need and importance in a child with a disability.

Ethnic minorities, ATSI, and students with low SES reflect the artist’s personality, as his history is closely connected with the constant struggle against discrimination. This story can be presented in the form of various team-building games when everyone is engaged in the same activity and has the same opportunity to show their inner creativity. It includes drawing sketches based on the artist’s style, either copying his paintings or giving the task of drawing a landscape of his native lands.

Further discussion can be developed with an exposition of works in the next lesson, where students will look for parallels with the artist’s style or give the children the opportunity to talk about their work, thereby making the most straightforward project activity. An important point is the feedback that both students and the teacher will give, introducing facts from the artist’s life and giving students food for thought and discussion. As a result, regardless of background, students can recognize the distinctive color of each other’s cultures and develop a sense of respect in this respect.

The study of English as a second language in this situation again correlates with the life of Namatjira, who was faced with the need to adapt to other societies. It is possible to implement such adaptation mechanisms in a simplified form to a small community of the class team to improve familiarization with the culture of the language. It is important to note that learning English is quite successful and is often woven into the CLIL methodology when the lesson is filled with thematic meaning with related disciplines (Coyle, 2018). Finally, project activity is much more helpful in this situation, which involves reading, listening, and searching for information in a foreign language. The result is comprehensive training based on the story of the artist Namatjira.

Summary

The use of history and the work of artist Albert Namatjira in teaching second-stage students can be used in various playful and interactive ways to instill inclusive values and an educational function. The personality of the artist, combined with captivating landscapes of a recognizable style, can serve as the basis for a long-term program with the gradual introduction of various tasks aimed at developing communication and professional skills. Finally, even in a team with diverse learners, this topic positively affects various educational methods with a factual basis and ready-made visual accompaniment.

References

Aitken, W., & Wareham, C. (2017). The narratives of Albert Namatjira. Australian Aboriginal Studies, (1), 56-68. Web.

Coyle, D. (2018). The place of CLIL in (bilingual) education. Theory Into Practice, 57(3), 166-176. Web.

Giffard-Foret, P. (2018). Settling Scores: Albert Namatjira’s Legacy. Commonwealth Essays and Studies, 41(41.1), 31-42. Web.

Gurr, D. (2020). Australia: The Australian education system. In Educational Authorities and the Schools (pp. 311-331). Springer, Cham. Web.

McLean, I. (2018). Modernism and the Art of Albert Namatjira. Mapping Modernisms: Art, Indigeneity, Colonialism, 187-208. Web.

Namatjira, A. (1936). Central Australian Landscape [Painting]. Charles Nodrum Gallery, Richmond, Australia. Web.

Namatjira, A. (1937). Ajantzi Waterhole [Painting]. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia. Web.

Probosiwi, P., & Hastuti, Y. (2019). Visual aesthetics understanding of elementary students in creating the artworks. International Journal of Visual and Performing Arts, 1(2), 80-89.

Sanchez, J. E., DeFlorio, L., Wiest, L. R., & Oikonomidoy, E. (2018). Student perceptions of inclusiveness in a college of education with respect to diversity. College Student Journal, 52(3), 397-409. Web.

Wall, J. (Ed.). (2022). The cultural value of trees: folk value and biocultural conservation. Taylor & Francis.

Williams, C. (2007). Albert Namatjira: the rich heritage of our desert earth painter.Australian Humanities Review, 43. Web.