Introduction and background information

Over the past one hundred years, the rates and extents of deforestation in the Amazon rain forest have been alarming (Coello, 2016). Almost 20% of the Amazon rainforest has been destroyed by the devastating deforestation. Activities such as agriculture, urbanization, settlement, and globalization have had adverse effects on the rainforest’s ecosystem (Vieira, Toledo, Silva, & Higuchi, 2008). The huge destruction in the rainforest happens disregarding the fact that the Amazon is the source of life to thousands of species and is oftentimes referred to as the lungs of the planet.

The Amazon rainforest spreads over the territorial boundaries of nine countries in the Americas and accounts for more than half of the rest of the global rainforest (Vieira et al., 2008). The Amazon Basin and the Amazon River are some of the most important environments in the world supporting various flora and fauna species. In addition, human beings highly depend on the rainforest.

Some of the key factors causing the Amazonian deforestation include farming (soya cultivation and beef cattle farming). It is worth noting that both beef farmers and soya growers use approximately 75% of the deforested land, especially the newly deforested land.

The Amazonian deforestation is a perfect example of the critical dilemma that faces environmentalists globally on how the balance between economic development and biodiversity protection should be attained (Ladlei, Malhado, Todd, & Malhado, 2010; Coello, 2016; Pfaff, Robalino, Herrera, & Sandoval, 2015)

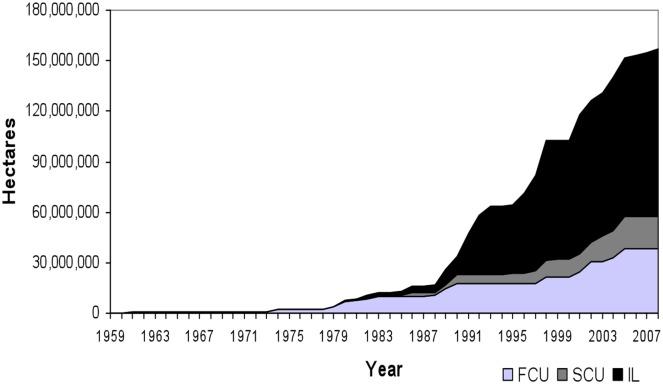

Prior to 2004, the Amazon was adversely affected by deforestation. Nonetheless, since 2004, the rates of deforestation dropped drastically for approximately 10 years. A key drop in the Amazonian deforestation was noted in Brazil after policies such as land protection and planned beef and soya farming were implemented. The civil society and NGOs played significant roles in increasing pressure to deforesters. Furthermore, The Central Bank of Brazil made it compulsory that all organizations that were seeking financial assistance from any bank should be compliant with environmental conservation policies. In addition, the South American region received support from the rest of the world. For instance, in 2007, Norway made significant financial contributions towards the fight against tropical deforestation (Boucher, 2014).

However, in 2014, reports of surging rates of Amazonian deforestation were made. Probably, the Brazilian government and other stakeholders reduced the swiftness and the enthusiasm they had in fighting deforestation. Reports of lack of political will were also made. It is worrying that if the 2014 trends continue, devastating deforestation is likely to be witnessed in the future.

Literature review

Spracklen, and Garcia-Carreras (2015) noted that the Amazon rain forest is a vital component of the global climatic system and, thus, it greatly influences not only the American climate but also the climatic and weather patterns in other parts of the earth. As such, the conditions/states of the Amazon ecosystem highly influence global climate (influencing global climatic phenomenon such as global warming).

Cutting of trees in the Amazon, therefore, has global climatic repercussions. Significant changes in the in energy and water balance are some of the apparent adverse effects of the Amazon deforestation. The meta-analysis of studies done by Spracklen, and Garcia-Carreras (2015) revealed a negative linear relationship between rainfall and deforestation extents implying that less rainfall is experienced when more deforestation is done on The Amazon. For instance, the deforestation in the Amazon rainforest accounted for the drastic drop in the regions annual mean 2010 rainfall by 1.8 ± 0.3%. The study also noted that the earlier studies that adopted nonlinear relationships hindered information correctness and, consequently, explaining the inconsistencies and incorrectness in the data pertaining the rate of rainfall drop and deforestation.

On the hypothetical grounds that the deforestation in the basin is not checked, Spracklen, and Garcia-Carreras (2015) estimated that by 2050, 8.1 ± 1.4% reduction in annual mean would be experienced in the region.

Solinge (2014) carried out a study on some of the legal issues surrounding the deforestation in the Amazon. He highlighted the need to adopt a green criminology perspective in studies on tropical deforestation. The study adopted ethnographic research method to get information concerning the legal and ethical aspects of the tropical deforestation. The study compared illegal deforestation with corruption and violence.

Moraes, Franchito, and Rao (2013) investigated the impacts of land changes that result from deforestation and the implications of the Amazonian deforestation on global warming and the climatic patterns in the world. It was evident that tropical deforestation had huge effects on global warming, evapotranspiration, and precipitation.

Countries in the Amazon region adopt various policies to curb deforestation and the consequent loss of indigenous species. Pfaff et al., (2015) investigated the efficacy of using protected areas as a way of averting deforestation. It was evident that using protection along the land with high settlements and/or developmental pressures was more effective than on lands facing low pressure.

Boucher (2014) noted that the Amazonian deforestation had significantly dropped from 2006, especially along the Brazilian Amazon, which registered a 70% drop. The significant drop was not expected since during the nine years, the global prices of beef and soya registered increases. It is imperative to note that the global demands for beef and soya are the chief proximate causes of deforestation. As such, previous increases on the two products’ prices resulted in increased deforestation in the Amazon rainforest.

Moreover, Boucher (2014) showed that Brazil made noteworthy efforts in reducing emission from tropical deforestation. The study attributed the positive results over the nine-year period to good leadership, the Norway’s pledge incentives, proper law implementation, pressure from environmental conservationists, NGOs, and the civil society.

However, studies indicate that from mid-2014, the rates of deforestation in the Amazon soared drastically (Fearnside, 2015). The Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research reveals that since August 2014, more forest is being lost, contrary to what was earlier estimated. Monthly averages are more than twice the averages of the months of the years 2012 and 2013.

Deforestation seems to have adverse effects on the Brazil economy with the local currency and the exchange rates going down with the escalating deforestation. Comparing the profitability of Brazilian exports between the period when deforestation was low and after mid-2014, Fearnside (2015) realizes that the exports are less profitable with escalating deforestation.

Moreover, Fearnside (2015) observes that the Brazil government is now less committed to the fight against deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. Notably, the 2008 policy by the Central Bank of Brazil, which required that all financing from financial banks be accompanied by proper searches on environmental conservation, is facing the lack of political goodwill. In addition, protected areas are no longer created like before with some protected areas being retitled as unprotected. Further, the government has drastically reduced resource allocation to the fight against deforestation and law enforcement by more than 70%.

Discussions

Deforestation in the Amazon has a long history that dates back to the early 20th century. During the second half of the 20th century, the extents and rates of deforestation in the Amazon and other tropical regions increased sharply raising worldwide concerns (Boucher, 2014). In the 1960s, the Amazon was violently occupied following the regional need to develop the economy.

Environmental degradation and exploitation of natural resources were done hastily with little or no consideration on the peculiar and diverse natural species. Over time, the extents, and rates of deforestation have been increasing.

Causes of deforestation in the Amazon rainforest

There are numerous and complex factors that result in deforestation of the Amazon rainforest. According to Coello (2016), “deforestation is caused by a complex web of interrelated factors there is no one cause or solution” (p. 62). It is worth that the topic of proximate and ultimate causes have been the subject of both the regional and global studies. Moreover, the regional and the global media houses have made significant reporting on both proximate and ultimate causes of deforestation in the Amazon rainforest.

It is generally agreed that soya production constitutes the greatest risk and is the chief cause of deforestation in the Amazon. Other predominant causes of deforestation include logging and beef farming.

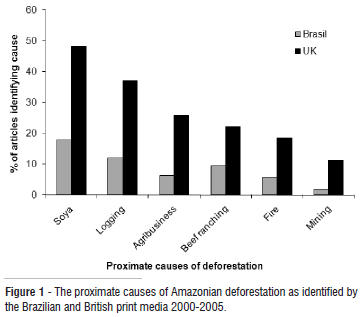

Ladlei et al. (2010) noted that the causes of deforestation in the amazon could be grouped into two broad categories as illustrated in the table below.

Source: (Ladlei et al., 2010).

Although many researchers and reporters generally agree on the grouping of the causes, there are huge discrepancies concerning the extent of the destruction by each cause. The complexities surrounding the subjectivity of reporting and politically instigated reasons are some of the explanations why different media houses report contrarily. As such, readers and news viewers are subjected to conflicting information concerning the extents of the destruction resulting from each of the various causes.

In addition, different media houses (in the region and internationally) report on each of the causes depending on their interests. For instance, Ladlei et al. (2010) demonstrated how the media in the UK differ from the media in Brazil concerning the frequencies on reporting on each of the major causes of deforestation in the Amazon rainforest.

The UK and other international countries have interests in the extent to which the soya cultivation affected the deforestation since they are the major importers of the agricultural products. Therefore, more articles on international demand as a source of deforestation are published in the UK than in Brazil. The Brazilian press has much interest in poor governance, soya production and, development as indicated by the frequency of reporting.

Annual and regional deforestation

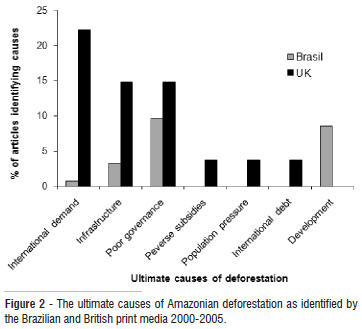

Various studies have been done to investigate the rates and extents of deforestation in the Amazon rainforest. For instance, Song, Huang, Saatchi, Hansen, and Townshend (2015) while trying to investigate the extent of deforestation-related carbon emissions examined the annual rate at which Amazonian deforestation happened from 2000. The study revealed that between 2000 and 2010, approximately 16 million hectares, which was equivalent to almost 3% of the forest in 2000, was lost.

It was noted that Brazil constituted the biggest percentage of the Amazonian deforestation in that decade making 79% of the total deforestation. Bolivia came in second accounting for 12% of the total forest loss. Colombia and Peru contributed 8%.

The southeastern region was the most affected during the 10-year-period. The region, which is commonly referred to as the arc of deforestation, had the largest concentration of deforestation. It was also evident that deforestation was becoming more prevalent in the western region.

There were noticeable declining trends after 2005, findings that were in consistency with various reports. The drop was extremely drastic with Brazil’s contribution dropping from 87% at the beginning of the study to 54% at the end of the study (2010).

Other countries such as Peru and Bolivia had slight decreases in 2006. However, the trees loss in the Colombian Amazon escalated twofold between 2006 and 2009.

Effects of the Amazonian deforestation

Although the deforesters cite economic and agricultural gains as the key justifications for cutting down of trees in the Amazon rainforest, the negative effects exceed the said benefits. In addition, the benefits are not sustainable. Deforestation has many adverse effects, including carbon emissions, loss of biodiversity, unpredictable rain patterns, and global warming (Song et al., 2015; Moraes et al., 2013).

Mitigation efforts

Since the mid-20th century, deforestation has drastically reduced the forest cover in the Amazon region. The adverse effects are evident prompting governments, NGOs, civil society, and businesses to come up with deforestation mitigation measures and forest restoration programs (Docksai, 2013). Some of the efforts adopted include the creation of protected areas, civil society movements, and planned farming among others.

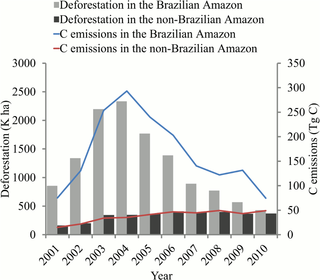

Protected areas

The use of protected areas is one of the most effective methods adopted by governments to curb the Amazonian deforestation (Pfaff et al., 2015). Brazil has predominantly used the method to protect forest loss from the late 1950s. However, most implementations were not realized until between 1990 and 1999.

Approximately, 5 million square kilometres of the Amazon rainforest is under the Brazilian protected areas. Brazilian authorities categorize the protected areas into three broad groups, including State Conservation Units (SCU), Indigenous Lands (IL), and Federal Conservation Units (FCU).

It is evident, from figure 4, that since the beginning of the 21st century more forest cover is under protected areas. This can be linked to the reduced extents of deforestation from 2000 (Pfaff, Robalino, Herrera, & Sandoval, 2015).

Activists’ movements and NGOs’ efforts

The civil society and NGOs have made significant efforts in fighting the Amazon deforestation menace (Boucher, 2014). For instance, the civil society and NGOs pressurized the region’s governments, the business people, and the farmers among other stakeholders and the sharp decline in the forest loss between 2000 and 2014 was realized.

For instance, the civil society has tried to fight environmental noncompliance by suing firms that defy anti-deforestation policies. In addition, the civil society has barred the financing of noncompliant companies. The United Cacao Limited SEZC, for instance, faces financing sanctions after civil society’s outcries (Hill, 2016).

Carefully planned agricultural practices

Crop plantation and beef farming constitutes the highest proximate causes of the Amazonian deforestation. As such, farmers in the region adopted moratorium farming and after some years, positive results were evident. In the 2009/2010 crop year, for instance, less than 0.5% of soya growing was done on the deforested region in the Brazilian Amazon. The moratorium efforts broke the strong links between deforestation and farming that existed since the beginning of the Amazonian deforestation. As such, even with the drastic increases in the global soya prices in 2007, deforestation resulting from soya farming significantly reduced. It is imperative to note that the use of international consumer boycotts highly influenced the regional beef and soya farming.

The international support

The efforts by the countries in the Amazon rainforest region to curb deforestation after 2004 attracted international aid. Brazil, for instance, demonstrated serious commitment to fight deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon when it implemented some significant environmental conservation regulations. The spirit of the Climate Change Law, for instance, endeavours to ensure that 40% of deforestation-related emissions are reduced by 2020.

The Brazilian commitment attracted the Norwegian government financial support. The Norwegian government gave to the Brazil’s Amazon Fund $1 billion to be used in the fight against forest loss. It is worth noting that the pledge was result oriented, and therefore, the money was to be released based on achievements. The program saw huge reductions in deforestation and subsequent carbon emissions making it the world largest program to fight tropical deforestation. Other countries, including Germany, the UK, and the US among other countries have demonstrated their support in fighting tropical deforestation and the related carbon emissions.

The future

The Amazon rainforest war is far from being concluded (Fearnside, 2015). The soaring deforestation rates that were rejuvenated in 2014 set a bad precedence for the future. In addition, the lack of political will, the economic meltdown and political instabilities in the Amazon region are some of the factors that increase the risks of deforestation in the future. However, pressure from the civil society, global leaders, and other stakeholders may keep the deforesters at check.

Conclusion

The Amazon rainforest is the largest rainforest in the world spreading through nine countries in the Americas. It is, therefore, a crucial region supporting various species of flora and fauna. In addition, the Amazon is a vital factor in the global climate with huge implications on carbon emission regulation and global warming.

However, the Amazon rainforest has been attacked by human activities leading to drastic loss of forest cover in over 50 years. There are various causes that have led to the extreme loss of forest including, agricultural activities, economic activities, development, fire, logging, and settlement among others.

Deforestation in the Amazon rainforest has adversely affected the South American region and the earth at large. Some of the key effects of the vice include loss of biodiversity, climate change, and carbon emission among others.

The regional and world governments, civil society, business, and activists have put substantial pressures on deforesters in attempts to reduce the rates of Amazonian deforestation and avoid the related consequences.

Various mitigation measures have been suggested and put in place to curb the Amazonian deforestation. Some of the key methods adopted include the use of protected areas and planned beef and soya farming.

The region has received international aid in the fight against Amazonian deforestation. The Norwegian government, for instance, made a five-year financial pledge to support tropical deforestation. It contributed $ 2.5 billion to fight deforestation from 2007. The Norwegian government also gave $1 billion to the fight against the Brazilian Amazon deforestation and the recovery of the lost forest cover.

The mitigation measures adopted have proved effective reducing drastically the rate of deforestation in the amazon from 2000 to 2014. However, their efficacy was thwarted in the second part of 2014 when the rates of deforestation increased again.

Recommendations

- Cooperation among all the stakeholders, including political leadership, business organizations, civil societies, and other members of the public should be embraced to curb the Amazon rainforest deforestation.

- Data concerning the extents and the rates of deforestation and its effects should be harmonized and made more accurate to allow proper policy formulations. The regional media should make correct reporting on causes and effects of deforestation in the Amazon rainforest.

- More stringent punishment and heftier penalties should be imposed on any person(s) convicted with illegal deforestation.

- The policies set to safeguard the protected areas should be fully implemented. The political class and the government should ensure that the mitigation that led to the earlier drops in deforestation are improved.

- Agriculture, settlement, and other human activities should be done in the unprotected areas following set policies, which should be aimed at conserving the Amazon from further deforestation.

- More research should be done on conservation methods, including evaluating the effectiveness of the currently adopted techniques.

- More support from the international bodies and governments is necessitated by the new waves of deforestation in the Amazon.

References

Boucher, D. (2014). How Brazil Has Dramatically Reduced Tropical Deforestation. Solutions Journal, 5(2), 66-75.

Coello, J. J. (2016). Forest Economies: A Remedy to Amazonian Deforestation? The Indiana University Journal of Underground Research, 2(1), 63-71.

Docksai, R. (2013). Disappearing Forests? Actions to Save the World’s Trees. The Futurist, 47(5), 45.

Fearnside, P. M. (2015). Environment: Deforestation Soars in the Amazon. International Weekly Journal of Science, 521(7553), Web.

Hill, D. (2016). Will London Stock Exchange bar firm over Amazon deforestation? Retrieved from The Guardian. Web.

Ladlei, R. J., Malhado, A. C., Todd, P. A., & Malhado, A. C. (2010). Perceptions of Amazonian deforestation in the British and Brazilian media. Acta Amazonica, 40(2).

Moraes, E. C., Franchito, S. H., & Rao, V. B. (2013). Amazonian Deforestation: Impact of Global Warming on the Energy Balance and Climate. American Meteorological Society , Web.

Pfaff, A., Robalino, J., Herrera, D., & Sandoval, C. (2015). Protected Areas’ Impacts on Brazilian Amazon Deforestation: Examining Conservation – Development Interactions to Inform Planning. PLoS One, 10(7). Web.

Reuters Daily Mail. (2015). Brazil’s vanishing jungle: Haunting images from the Amazon shed light on ongoing destruction of world’s largest intact rainforest. Web.

Solinge, T. B. (2014). Researching Illegal Logging and Deforestation. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy, 3(2). Web.

Song, X.-P., Huang, C., Saatchi, S. S., Hansen, M. C., & Townshend, J. R. (2015). Annual Carbon Emissions from Deforestation in the Amazon Basin between 2000 and 2010. Plose One. Web.

Spracklen, V. D., & Garcia-Carreras, L. (2015). The impact of Amazonian deforestation on Amazon basin rainfall. Geophysical Research Letters, 42(21), 9546–9552. Web.

Vieira, I., Toledo, P., Silva, J., & Higuchi, H. (2008). Deforestation and Threats to the Biodiversity of Amazonia. Brazilian Journal of Biology, 68(4).