The Energy and Environmental Council of Japan (2012) points out that, the oil price shock that was experienced in 1973 had a fundamental impact, as far as the energy policies of many countries is concerned.

According to The Energy and Environmental Council of Japan (2012), this event resulted in many countries reconsidering their energy policies, whereby many countries started considering implementing policies that will secure their energy supplies in the event of a global energy crisis.

Most countries, including the United States, sought for policies that would reduce their dependence on fossil based energy sources, but instead encourage the use of renewable energy sources.

In addition to being environmental friendly, they would ensure that they are in a position to attain some degree of independence, as far as the supply and consumption of energy is concerned (Johansson, 2007).

Since this period, the governments of many countries have turned to alternative energy sources such as geothermal, solar power, and hydro-electric energy to supplement their use of fossil based energy.

In the long run, this has enabled them to significantly reduce their dependence on fossil energy (Maczulak, 2003).

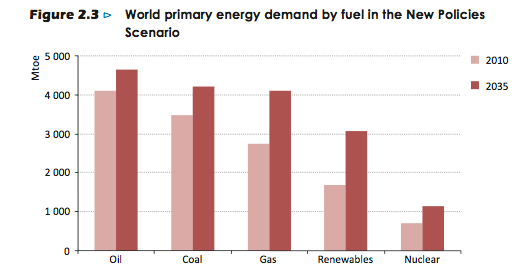

As much as there has been considerable success on this front, Toyoda (2012) points out that the level of use of these environmentally friendly renewable energy sources has largely remained insignificant, as compared to most country’s overall energy consumption.

This has resulted to a situation where most countries still heavily rely on fossil based energy sources, despite the presence of numerous policies aimed at limiting their use.

In addition to the alternative (green) energy sources, another source of energy that has been and is still in use by many of the developed countries is nuclear energy (Rathore & Panwar, 2007).

Nuclear energy is produced as a result of several chemical and physical reactions that result in either the splitting of the atom’s nuclei or the fusion (joining) of the atom’s nuclei.

There are several advantages associated with nuclear energy, as compared to some of the convectional energy sources, including oil and coal.

First and foremost, nuclear energy can be used indefinitely unlike oil or coal, whose supply might run out in the long run (Meltzer, 2012). Secondly, nucleic reactions which form the basis of nuclear energy produce more energy than all of the other energy sources, making nuclear energy one of the best sources of energy available.

Finally, production of nuclear energy results in less pollution of the environment in terms of addition of greenhouse gases to the environment, than production of most of the other convectional sources of energy (Jarvela, 2011)).

Be that as it may, the use of nuclear energy is still limited at bets to only a few developed countries that have the capital and the technology to produce this source of energy.

(Gallagher, 2009) notes that in addition to its associated costs, production of nuclear energy involves the use of potentially dangerous reactions that need careful planning and implementation and in case anything goes wrong, the effects of this error can be catastrophic.

Japan is one such country that not only relies on nuclear energy as one of its main sources of energy but has also experienced firsthand some of the catastrophic effects of botched up nuclear reactions.

De Miguel, Labandeira and Manzano (2006) point out that the Fukushima nuclear energy disaster is one of the most notable nuclear energy disasters experienced in modern times.

It resulted in the death of several people and displacement of hundreds of thousands of people who fled their homes in an effort to prevent them being exposed to radioactive materials.

The magnitude of this disaster was so immense that it has resulted in a complete shift in Japan’s energy policy, whereby the country has now renewed its efforts for the search of a viable alternative energy source, that will significantly reduce its over reliance on nuclear energy.

This paper will discuss Japan’s energy policy, including the impact of Fukushima nuclear disaster in shaping this policy.

Frogatt, Mitchell & Monagi (2012) point out that in light of the Fukushima nuclear disaster and other catastrophic events, such as the recent earthquake, that have adversely affected the country, Japan has started out on a path towards implementing an energy policy that will see reevaluation of the role of nuclear power in its economy.

This is in an effort to significantly reducing the country’s overreliance on this source of energy, and also to renew its environmental conservation efforts.

According to Frogatt, Mitchell & Monagi (2012), Japan is seeking to implement programmes that will directly result in increased use of renewable energy sources and also in the short term, see it increase its use of fossil based energy sources, all in an effort to scale down on the use of nuclear energy.

This policy has seen the country temporarily close down some of its nuclear power plants with and those that remain in operation are being supplemented with other sources of energy.

Being the third largest economy in the world, Japan’s energy policy is likely to have significant global ramifications as far as global energy trends and other related aspects are concerned.

Frogatt, Mitchell & Monagi (2012) note that this position also implies that Japan is one of the countries with the highest energy consumption rates and in order to maintain its economic status, the country will have to ensure that despite its new energy policy, it still has the capacity to efficiently maintain its production capacity and this essentially implies that it will have to maintain its energy consumption at more or less the same level as they are today.

However, Kingston (2012) points out that Japan has limited capacity to fulfill its energy needs from local sources, consequently, the country will have to source for this energy from the international market.

Such a scenario, as pointed out by Kingston (2012), will greatly impact global energy prices and availability since the country’s high energy demand will imply that is likely to affect global energy supply.

According to The Energy and Environmental Council of Japan (2012), there are three main objectives that will guide the implementation of Japan’s new energy policy. The first objective is for the country to reduce its over reliance in nuclear energy.

According to The Energy and Environmental Council of Japan (2012), this is the most immediate of all the three objectives and therefore most of the short-term implementation details of the new energy policy are actually aimed at ensuring that this objective is attained as soon as possible.

Due to the urgency with which this objective is to be attained, the policy seeks to ensure that the country has completely done away with nuclear energy sources by the year 2030.

Currently, nuclear power usage is being closely monitored and only those plants that have passed the safety test are in operation (The Energy and Environmental Council of Japan, 2012).

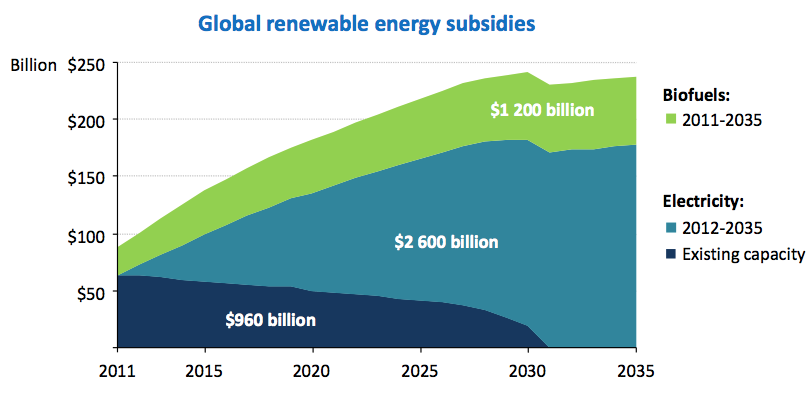

The second objective of the Japan’s new energy policy is to encourage “the realization of a green energy revolution” (The Energy and Environmental Council of Japan, 2012 p. 4).

This objective aims at ensuring that in addition to simply doing away with nuclear energy sources, the country adopts the usage of environmental friendly energy sources whose usage will have no significant negative impact on the environment.

According to The Energy and Environmental Council of Japan (2012), this objective champions the use of renewable sources of energy such as solar, wind and geothermal hose use will see the country greatly increase its energy security while at the same time reducing the harm done to the environment.

In order to achieve this objective, the Japanese public should be educated on the benefits and need to adopt the usage of these renewable and environmental friendly sources of energy.

This will increase social awareness among the general population who will appreciate and promote energy initiatives meant to address environmental issues.

The third and final objective of the new energy policy is to enhance the country’s energy security. This objective aims at ensuring that the country supply of energy is stable and assured.

This objective will therefore see more emphasis being placed on energy sources whose supply is likely to be maintained at a steady rate in the foreseeable future period.

In addition to that, the new policy will see initiatives being implemented that will be aimed at promoting efficient energy use that will result to minimal wastage (The Energy and Environmental Council of Japan, 2012.

Moreover, the policy will also see renewed efforts being placed on research for the new and more efficient energy sources that are likely to increase the country’s overall energy security.

The market dynamics specifically the supply and demand aspects of the market is also an issue that can potentially interfere with stable supply of energy and for this reason, the new policy aims at ensuring that among other things, there is increased regulation of these two aspects.

The Energy and Environmental Council of Japan (2012) points out that one of the ways that the policy proposes to address this issue is through the elimination of monopolies in the energy sector whose activities are likely to interfere with stable energy supply.

Moreover, the Energy and Environmental Council of Japan (2012) explains that the separation of the two functions of supply and generation of electricity will also go a long way in ensuring that supply is maintained at a steady rate.

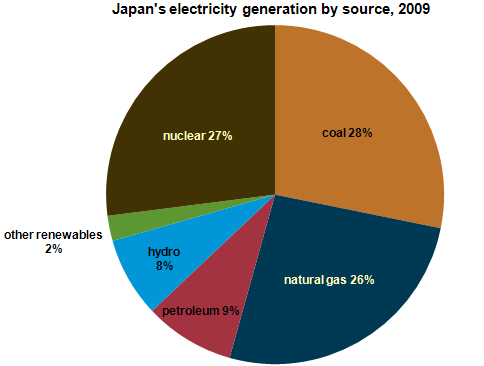

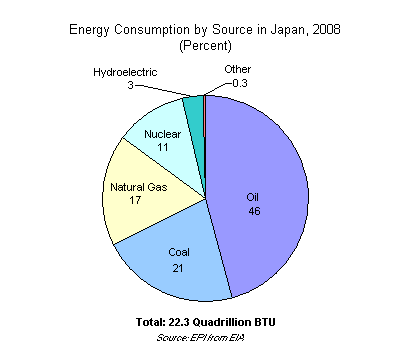

An analysis of Japan’s current energy generation mix reveals that nuclear energy accounts for 26 percent of the total energy generated in the country (Meltzer, 2010).

Other sources include liquid petroleum gas which accounts for 28 percent, coal which accounts for 25 percent, petroleum which accounts for 13 percent and finally renewable energy which accounts for a mere 9 percent with the majority of this being from hydro electric power (Meltzer, 2010).

This generation mix reveals how little emphasis has been placed on renewable energy sources; however, the new policy seeks to alter this situation whereby more emphasis will be placed on the generation of renewable energy as the country gradually increases it reliance on this energy source while at the same time reducing its reliance on the other energy sources.

Elliot (2012) points out that new policy implementation are usually tricky affairs and are normally faced with a myriad of challenges including strong opposition from parties who still favor the old policies.

Indeed, Schuman (2012) notes that many countries have tried to implement new energy policies but have resorted to abandoning these policies midway through their implementation due to one challenge or the other.

One of the challenges on implementing a policy such as an energy policy is the costs associated with implementing such a policy.

Pendergrast (2011) asserts that a country wishing to implement a new energy policy will require a lot of resources including funds and manpower in order to successfully go through with the implementation.

In Japan’s case, a lot of money will go into undertaking research and actually setting up these renewable energy power plants.

In case the country then decides to abandon the policy midway through its implementation, the funds that will have gone into implementing the policy will go into waste and this can adversely affect the Japanese economy (Pendergrast, 2011).

In addition to committing a lot of funds into a project whose outcome is uncertain, another challenge that the Japanese government is likely to encounter in its energy policy implementation is the challenge of convincing the Japanese people that this is the bests move to make (Banerjee, Marcellino & Masten, 2009).

Moony and Lanza (2013) note that the current Japanese energy policy, in as much as it aims at reducing the country’s overreliance on nuclear energy, its objective is not to completely do away with this vital energy source in the short term.

It aims at integrating it with other renewable sources of energy in such a way that it is not the sole significant source of energy for the country, before eventually phasing it out in the long term. This, therefore, implies that even in the new policy, there are provisions for nuclear sources of energy that will be used in the short term.

However, these sources will significantly be complimented by other sources especially renewable ones. The problem present itself when it comes to convincing the Japanese people that nuclear energy will be safe for them, bearing in mind that they have witnessed some of the disastrous effects of this energy source firsthand.

The Fukushima nuclear disaster accorded the Japanese people an opportunity to witness and appreciate the risks associated with nuclear energy sources.

Consequently, most of them are apprehensive about this source of energy in so far as its environmental viability and potential to cause great harm to both the environment and the people is concerned (Byer, 2011).

This, therefore, implies that the Japanese government will have to go out of its way in reassuring the people of the safety of this source of energy, if it wishes to successfully implement the new policy as it is (Moony & Lanza, 2013).

In addition to having to deal with local opposition from its citizens, Japan also has to deal with international opposition.

Hamilton (2012) asserts that the new Japanese energy policy has been the subject of negative reception from various international stakeholders including the United States and Australia who have expressed their doubts on the practicality of such a policy given the current Japanese economic status.

On its part, Australia has expressed doubt as to whether Japan will be able to maintain its status as a major global economic player if it adopts such a policy (Hamilton, 2012).

The United States on the other hand has based its opposition on the fact that this policy will inadvertently result to an increase in fossil fuel prices since Japan will have to source for most of its alternative fuel sources (with fossil fuel being significant source) from the international market (Oshitani, 2006).

This will in turn significantly increase the international demand for fossil fuel, thereby having the ripple effect of increasing fossil fuel prices across the board.

Moreover, the United States has also pointed out that Japan’s policy might compromise the international nuclear non-proliferation initiatives, which aim at ensuring that there is enhanced regulation of the movement of nuclear material (Morata & Sandoval, 2012).

Meyer (2011) points out that the new Japanese energy policy outlines several sources of energy that will be used both in the short term and in the long-term in order to effect its objective of reducing overreliance and eventually completely doing away with nuclear energy.

As already stated, in addition to reducing overreliance on nuclear energy, Japan through its energy policy also aims at enhancing its environmental conservation efforts in the long run and therefore, as much as the policy stipulates various sources of energy such as fossil fuels and coal whose production and use is detrimental to the environment, the use of these sources is aimed to be provide a short-term solution but in the long-run, the country through its policy aims at ensuring that renewable energy sources will be the ones responsible for fulfilling most of the country’s energy requirements (Anceschi & Symons, 2011).

One of the sources that are aimed at reducing the country’s over reliance on nuclear energy is natural gas. According to the current data available on energy usage, natural gas is one of the major sources of energy for Japan.

However, if the new energy policy is successfully implemented, natural gas is likely to be on of the major beneficiaries as the plan proposed an increase in the use of this energy source (Henze, 2012).

Byer (2011) points out that one of the factors that have made the country place more emphasis on natural gas as one of the main sources of energy is the new technology, that has emerged in the United States and has significantly improved the production of natural gas.

This technology has seen the use of efficient drilling techniques that have significantly increased the efficiency with which natural gas is produced. This is likely to increase the global supply of natural gas in the long-term (Perelman, 2011).

An increase in the supply of natural gas will enhance its reliability and also result in the reduction of natural gas prices across the board and therefore greatly benefiting those countries that rely on it as their major source of energy (Sovacool & Valentine, 2012).

In addition to natural gas, another energy source that can be employed to reduce Japan’s overreliance on natural gas is coal. Currently, coal is one of the major sources of energy for Japan. However, Kummel (2011) points out that the implementation of the new energy policy is likely to see an increase in the usage of coal.

The previous energy plan of Japan sought to actually decrease the amount of coal energy used in the country, but the new energy plan formulated after the Fukushima nuclear disaster actually seeks to increase the usage of this source of energy in the short-term.

However, the long-term objective of this policy is to reduce the usage of cola energy and other such energy sources whose production and usage impacts negatively on the environment (Kingston, 2012).

The third source of energy beside natural gas and cola that will be important in reducing Japan’s overreliance on coal energy is oil. Currently, oil is one of the major sources of energy in Japan and the new energy policy seeks to maintain the current levels of oil usage (Lusted, 2011).

Michaelides (2012) asserts that Japan has one of the largest consumption of oil. According to global oil consumption data, Japan is the third largest consumer of oil with the United States being first and China being second.

This therefore means that oil can replace nuclear as the major source of energy in the short-term if it is properly balanced by the other sources of energy (Solway, 2009).

All in all, Japan is a country that is still emerging from one of the most devastating nuclear disasters in modern day history. Presently, Japan still largely relies on nuclear energy as its main source of energy. However, the Fukushima nuclear disaster has acted as a wakeup call as far as the country’s energy sector is concerned.

Japan is now at an advanced stage at implementing a new energy policy that will see it greatly reduce its overreliance on nuclear energy in the short-term, and completely do away with this source of energy in the long-term (Gallagher, 2009). There are three objectives that will guide the implementation of this new policy.

The first objective seeks to reduce the country’s overreliance on nuclear oil before eventually phasing it out.

The second objective of this policy is aimed at encouraging the use of renewable sources of energy as a replacement for convectional energy sources. The third objective seeks to enhance the country’s energy security (Baumol, 1967).

The Japanese government is likely to be faced with several challenges in implementing this new energy policy. Some of these challenges include the monetary aspect of implementing the policy, convincing people on some of the implementation details of the policy, and opposition from the international community.

The country will have to effectively address these challenges if it wants to successfully implement this new policy. Failure to address any of them might result in the policy not being implemented at all or being partly implemented.

In order to reduce over reliance on nuclear energy and eventually completely do away with this source of energy, the Japanese government will have to employ the use of other alternative sources of energy or increase the use of some of the energy sources that are already in use in the country.

These include coal, oil, and natural gas (Banerjee, Marcellino & Masten, 2009). Japan plans to increase its usage of coal in the short-term, but the long-term outlook of the policy actually seeks to eventually do away with this source of energy because of its environmental effects.

When it comes to oil, Japan plans to maintain its current consumption rates as the country is already one of the largest consumers of oil However, in the case of natural gas, the policy seeks to increase its usage.

References

Anceschi, L & Symons, M 2011. Energy Security in the Era of Climate Change: The Asia-Pacific Experience, Palgrave, New York.

Banerjee, A, Marcellino, M & Masten, I 2009,Forecasting macroeconomic variables using diffusion indexes in short samples with structural change, Emerald Group Publishing Limited, London.

Baumol, W. J 1967, “Macroeconomics of unbalanced growth: the anatomy of urban crisis”, The American Economic Review, vol. 57no. 3, pp. 415-426.

Byer, R. J. 2011, A Rational Energy Policy, Xlibris, Pennsylvania.

De Miguel, K. & Labandeira, I. 2006, Economic Modeling of Climate Change And Energy Policies, Edward Elgar Publishing, London.

Elliot, D. 2012, Fukushima: Impacts and Implications, Macmillan, London.

Frogatt, A., Mitchell, C. & Managi, S .2012, Reset or Restart? The Impact of Fukushima on the Japanese and German Energy Sectors, EERG, Munich.

Gallagher, S. 2009, Acting in Time on Energy Policy, Brookings, London.

Hamilton, K. 2012, Energy Policy Analysis: A Conceptual Framework, M.E Sharpe, London.

Henze, T. 2012, Nuclear power in Germany – History and future prospects, GRIN Publishers, New York.

Jarvela, M. 2011, Energy, Policy, and the Environment, Springer, London.

Johansson, B. 2007, Renewable Energy: Sources for Fuels and Electricity, Island Press, Michigan.

Kingston, J. 2012, Natural Disaster and Nuclear Crisis in Japan: Response and Recovery After Japan’s 3/11, John Wiley & Sons, Boston.

Kummel, R. 2011, The Second Law of Economics, Springer, London.

Lusted, M. A. 2011, Japan Disasters, ABDO, New Jersey.

Maczulak, A. 2003, Renewable Energy: Sources and Methods, infobase, Philadelphia.

Meltzer, J. 2011, After Fukushima: What’s Next for Japan’s Energy and Climate Change Policy, Brookings, London.

Meyer, C. 2011, China Or Japan: Which Will Lead Asia,? Hurts Publishers, New Jersey.

Michaelides, E. E 2012, Alternative Energy Sources, Springer, London.

Moony, I. & Lanza, K. 2013, De-Centering Cold War History: Local and Global Change, Routledge, London.

Morata, L. & Sandoval, K. 2012, European Energy Policy: An Environmental Approach, Edward Elgar Publishing, London.

Oshitani, S. 2006, Global Warming Policy in Japan and Britain: Interactions Between Institution and Issue characteristics, Manchester University Press, Manchester.

Pendergrast, M. 2011, Japan’s Tipping Point: Crucial Choices in the Post-Fukushima World, Cengage Learning, New York.

Perelman, J. 2011, Energy Innovation – Fixing the Technical Fix, Lewis Perelman, San Diego.

Rathore, P. & Panwar, L. 2007, Renewable Energy Sources for Sustainable Development, New India Publishing, New Hampshire.

Schuman, F. 2012, Schuman Report on Europe: State of the Union 2012, Springer, London.

Solway, A. 2009, Renewable Energy Sources, Heinemann, New York.

Sovacool, K. & Valentine, J. 2012, The International Politics of Nuclear Power, Routledge, London.

The Energy and Environmental Council of Japan, 2012, Innovative Strategy for energy and the environment, The Energy and environmental Council of Japan, Tokyo.

Toyoda, M. 2013, Energy Policy in Japan: Challenges after Fukushima, IEE Press, Tokyo.