Morphology and life cycle

The adult Artemia is about 1cm long with a pair of stalked complex eyes, 11 pairs of thoracopods, sensory antennulae, and a linear digestive system. The male possesses a pair of the posterior penis, while the female has a conspicuous brood pouch located behind the thoracopods. Eggs grow in a pair of tubular ovaries situated in the abdomen (Van Stappen 41).

Normally, fertilized eggs grow into swimming nauplii following their release by the mother. However, in unfavorable conditions such as low O2 levels and high salinity, the embryo only grows up to the level of gastrula and gets cocooned and enters a state of dormancy prior to their release. Theoretically in all Artemia strains, females can switch in between oviparity and ovoviviparity mode of reproduction (Van Stappen 87).

In its natural habitat at the appropriate time, Artemisia lays biconcave-shaped cysts which float on the water surface to be washed ashore by waves and wind. The cyst is metabolically dormant and does not undergo further development in dry conditions. However, when they get immersed in seawater the cysts absorb water, attain a spherical shape and the embryo inside the cyst resumes its metabolism. In 20 hrs time, the shell burst releasing the embryo which hangs beneath the shell and the hatching membrane burst to release a free-swimming nauplius shortly (Van Stappen 43).

The initial larval stage is 400-500µm long, brownish-orange in color, with a red-eye in the head area and three couples of appendages with distinct functions. The first antennae perform the sensory function, the second filter-feeding plus locomotory function, and the third appendage is the mandibles is used for food uptake. A large labrum ventrally situated performs food uptake from the filtering setae into the mouth.

The first larval stage thrives entirely on its yolk since its digestive tract is not yet fully developed. The second larvae stage can ingest substrates such as detritus, algal cells, and bacteria, ranging from 1-50µm. The larva develops through approximately 15 molts during which a pair of lobular attachments develop in the trunk region differentiating into thoracopods. Optimally the sea monkey can attain maturity in just 8 days and achieve a reproduction rate of up to 300 nauplii (cyst) after every 4 days with a lifespan of several months, (Browne 949).

Ecology and geographical distribution

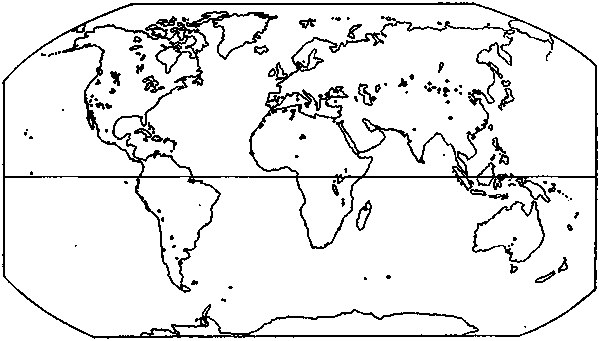

Artemia strains inhabit approximately 500 natural saline lakes as well as man-made salterns found across the tropical, temperate climates and subtropical regions of the world. However, the brine shrimp population is not continuous since not all salty biotopes are inhabited. Their physiological adaptation to highly salty waters for survival hinders their migration from one biotope to another through the sea. The “sea monkey” possesses a proper osmoregulatory system which allows it to synthesize respiratory pigments to cope with compromised O2 levels of elevated salinity; and the capacity to develop dormant cysts at extreme salinity. Therefore, Artemia inhabits waters with salinity hostile to its predators (70 g.l-1). However, the brine shrimp cannot survive in waters near and above 250 g.l-1 salinity (Persoone 18).

Artemia strains can adapt to varying environmental conditions including a temperature range between 6-350C, ionic composition and the salinity of the biotope. Thalassohaline waters (sea waters with NaCl as the main salt) compose most of the coastal brine shrimp habitats. Other thalassohaline habitats are interior; including the Great Salt Lake in Utah, US. Some biotopes have an ionic composition different from those of the seawaters in that they are sulphate waters including Chaplin Lake and Saskatchewan in Canada. Others are carbonate waters, like Mono Lake in California, and potassium concentrated waters like the Nebraska lakes (Van Stappen 88).

Artemisia sp. dispersion

The prominent agents of dispersion include waterfowl such as flamingos and wind. The nauphiils cling to the feathers and feet of the fowls and are able to resist digestion for a couple of days following their ingestion by the birds. This accounts for lack of Artemia sp in some suitable areas lacking the migratory birds; such as the biotopes of the northeastern coast of Brazil.

Works Cited

Browne, Robert. et al. Partitioning genetic and environmental components of reproduction and Lifespan in Artemia. Ecology, 65.3(1984): 949-960.

Persoone, George. General Aspects of the ecology and biogeography of Artemia. In: The brine shrimp Artemia. Vol. 3. Ecology, culturing, use in aquaculture. Persoone, G. et al. (Eds). Wetteren, Belgium: Universa Press 1980.

Tackaert, Wilson. Semi-intensive culturing in fertilized ponds. In: Artemia Biology. Browne A., Sorgeloos P. and Trotman C.N.A. (Eds). Boston, USA: CRC Press, 1991.

Vanhaecke P. Tackaert W. and Sorgeloos P. The biogeography of Artemia: an updated review. In: Artemia research and its applications. Vol. 1. Morphology, genetics, strain characterization, toxicology. Sorgeloos, P. Bengtson A. Decleir W. and Jaspers E. (Eds). Wetteren, Belgium: Universa Press, 1987.

Van Stappen, Gilbert. Introduction, biology and ecology of artemia.Fisheries and aquaculture Department. n.d. Web.