Introduction

Puberty is the development of bodily changes by which the body of a human child or juvenile develops to a matured body thereby, having the requisite qualities for reproduction. Puberty is produced by the secretion of an endocrine gland that is transmitted by the blood to the tissue on which it has specific communications from the brain to the gland in which gametes (sex cells) are produced.

In return, the gland in which gametes (sex cells) are produced produces a kind of secretion of an endocrine gland that is transmitted by the blood to the tissue which in turn acts as a stimulant for the development, function, or change in the human or child’s body system.

In line with this, biological unfolding of events involved in an organism changing gradually from a simple to a more complex level occurs in the earlier stage of puberty and ceases at the end of puberty. However, prior to puberty, the significant changes in the physical and body structures of both boys and girls are approximately limited to the external sex organ. At some stage in puberty, basic significant changes and function increases in various body organisms and formations.

Nevertheless, Puberty forms an excellent growth in puberty. Although it is commonly considered as the appearance in bodily form of secondary sexual characteristic, however there are large number of other important biological, psychological, and social changes associated to puberty.

Timing of the onset of puberty

The unanimously acknowledged description of adolescence is the bodily change of growth in the human bodily structure. These bodily alterations are the initial noticeable signs of nervous system, hormonal, and operational changes of gonads.

The period at which sex glands become functional alternate between individuals and in most cases, puberty starts around 10 and 13 years of age. This age is influenced by both hereditary and environmental aspects like dietary condition and communal conditions (Hayward, 2003). A young female who encounters considerable mutual or reciprocal action with male adults will begin puberty earlier than those who are not exposed excessively to adult males (Nelson, 2005, p.357).

Race can also affect the normal age at which adolescence begins. The initial occasion of menses in women in people analysed were of about the ages 12 and 18 years. It was discovered that black ladies were the first to commence puberty whereas the increase endurance populations are in Asia. However, at the advanced age, standards reveal dietary restrictions more than the diversities in genetic and have the possibility to alteration within a few age groups with a significant change in diet.

The average age for the first occurrence of menstruation in a woman may be an indicator of the percentage of starved girls in the populace, and the distance across its spread may replicate inequality of property and food allocation in a populace. Researchers managed to recognize an earlier age of the beginning of puberty. However, their opinion or judgment reached was based on an assessment of data over a long period of time (up to 10 years).

Overview of puberty differences between male and female

Differences between male and female puberty

The most evidential distinctions noticed in puberty both in girls and boys are the age it commences, and key sex hormones present. Consequently, in most cases, puberty in girls starts at age 10, whereas in boys it’s at age 12 (Alsaker, 1995). Just at it come early, it also ends a little bit early in girls than in boys, i.e. in girls it’s between the ages 15-17 and 16-18 in boys (Angold & Worthman, 1993).

Girls in most cases mature 4 years after the appearance of their initial bodily transformation of puberty. On the contrary, boys mature gradually for 6 years after the appearance of their initial bodily transformation of puberty (Garn, 1992)

In boys, the Male sex hormone that is produced in the testes and responsible for typical male sexual characteristics known as testosterone is the main internal secretion for sex. The abnormal development of male sexual characteristics is a key effect of potent androgenic hormone produced chiefly by the testes; responsible for the development of male secondary sex characteristics.

Before the commencement of puberty, boys are usually shorter than girls, but as time runs by and development takes place, the reverse is always the case since the adult male tend to increase in height more than the female adults.

In as much as boys are always some centimetres shorter than girls before they enter pubertal stage, this is usually never the case as they grow, for they become taller than the women counterparts. The internal secretion in charge of female development is known as estrogen.

While the female steroid sex hormones known as estradiol contributes to the progress or growth of soft fleshy milk-secreting glandular organs on the chest of a woman and womb, it is also the most important hormone operating the pubertal development and epiphysial growth and conclusion (MacGillivray, Morishima, Conte, Grumbach,& Smith, 1998).

Physical changes in male teenagers

Testicular size, function, and fertility

In male teenagers, testicular act of increasing in size is the primary physical sign of puberty. However, the size of the teenage male testes keeps increasing all through puberty, thereby developing up to the best possible adult size within six years subsequent to the beginning of puberty. Once the testicles have excessively enlarged as a result of increased size in the constituent cells the penis will also become larger or bigger to adult size (Jones, 2006).

One of the two male reproductive glands that produce spermatozoa and secrete androgens has two main tasks which are: (1) to produce the secretion of an endocrine gland that is transmitted by the blood to the tissue on which it has a specific effect and (2) to produce the male gamete. The cell in the testes secretes the hormone to produce testosterone, which in succession produces the majority of the male pubertal transforms.

The Spermatozoa can be noticed in the early hour’s liquid excretory product of most male teenagers following the early year of life when sex glands become functional, or sometimes earlier. Typically, potential state of being fertile in boy’s starts when they are thirteen years old, but complete state of being fertile is attained within one to three years after the start of fertility.

Prepuce retraction

At some stage in puberty, or earlier than, the tip and empty space of a teenage male’s prepuce becomes broader, gradually providing opportunity for pull back along the beam of the male organ of copulation and behind the small rounded structure; at the end of the penis, which as the end result of the process should be achievable without pain or complexity.

The pliable sheet of tissue that covers or lines or connects the organs or cells that attaches the interior surface of the prepuce with the glans loses cohesion or unity and frees the prepuce to break out of the glans. The prepuce then progressively becomes capable of being retracted.

Pubic hair

Pubic hair in many cases or instances becomes visible on a teenage male subsequent to the growth of the genital organ. The pubic hairs are generally first observable at the abaxial part of the penis nearest its point of attachment.

Furthermore, subsequent to the manifestation of pubic hair, other parts of the skin that acts in response to male sex hormone that is produced in the testes and responsible for typical male sexual characteristics possibly will grow androgenic covering for some parts of the body consisting of a dense growth of threadlike structures. There is an outsized difference in quantity of body hair in fully developed male and considerable distinctions in growth and quantity of hair among diverse cultural and genetic race.

In line with this, the beards and moustache is frequently noticed in late teenage years of male children, but may not be fully observed until later in their puberty age. Facial hair will continue growing harsher, blacker and more intense for an additional years following puberty. Some men do not grow complete facial hair for the period of ten years following the end of puberty. Nevertheless, Chest hair may be perceived at some point in puberty or some period of time, however, not all male adult grow or possess hair in the chest.

Voice change

With the aid of male sex hormone produced in the testes and responsible for typical male sexual characteristics, the cartilaginous structure at the top of the trachea which contains elastic vocal cords that are the source of the vocal tone in speech, develops in both male and female teenagers. This development is higher in male teenagers, thereby, deepening their voice.

Male musculature and body shape

During the end of the period of puberty in mature men, they experience change in their bone structure since the bones become heavier and almost two times the skeletal contractile organs of the body. Some of the bone development is excessively greater, consequential to distinctly changed masculine and feminine skeletal forms. Consequently, the skeletal muscle changes mostly at some point of puberty, and muscle increase can prolong even after boys are physically fully developed.

Body smell and Acne

Increasing structures of androgens can transform the class of aliphatic monocarboxylic acids that form part of a lipid molecule and can be derived from fat by hydrolysis which, results in a severe mature body smell.

As in young female teenagers, a different androgen outcome is augmented emission of the oily secretion of the sebaceous glands from the skin and the consequential inconsistent number of acne. Accordingly, acne cannot be avoided or effortlessly impaired by diminution, except it generally completely reduces at the last part of puberty.

Physical changes in female teenagers

- Breast Development. The primary bodily perceptible indication of puberty in female teenagers is typically a firm, soft abnormal protuberance under the midpoint of the small circular area such as that around the nipple of the breasts, and appears during their tenth years of maturity (Litt, 1999)

- Pubic hair. Pubic hair is frequently the subsequent obvious change at the teenage female stage of puberty, typically within some months of the start of breast development in a female at the beginning of puberty (Tanner & Davies, 1985). It is commonly called pubarche.

The female pubic hairs are at first frequently noticeable beside the liplike structure that bounds bodily orifice. However, in approximately fifteen percent of teenage girls, the first pubic hair comes into views before breast maturity starts (Tanner & Davies, 1985). - Vagina, uterus, ovaries. The surface of the mucous membranes of the vagina transforms in reaction to growing levels of the female steroid sex hormones that are secreted by the ovary and responsible for typical female sexual characteristics, and getting more intense and very low in saturation pink colour (compare to the more colourful red of the prepubescent vagina mucous membrane) (Siegel, & Surratt, 1992). In relation to this, milk-like secretions are typical end product of female steroid sex hormones that are secreted by the ovary and responsible for typical female sexual characteristics (Zuckerman, 2009) Nonetheless, in the two years subsequent to the start of breast development in a woman at the beginning of puberty, the hollow muscular organ in the pelvic cavity of females, the female internal reproductive organ, and the small spherical group of cells containing a cavity in the ovaries add to its size. In line with this, the female internal reproductive organ generally include small follicular vesicles which is only detectable by very high frequency sound; used in ultrasonography (Siegel & Surratt,1992)

- Menstruation and fertility. The prime occurrence of menstrual blood flow from a ruptured blood vessel is called menarche, and naturally exists about two years following start of breast development in a woman at the beginning of puberty (Tanner & Davies, 1985). However, the standard age of menarche in young female adolescence is eleven years and the period of menstrual monthly discharge of blood from the uterus of non-pregnant women from puberty to menopause is not constantly in accordance with fixed order in the first two years following the first occurrence of menstruation in a woman (Apter, 1980). The expulsion of an ovum from the ovary is needed for fertility, but may either go with the first monthly discharge of blood from the uterus of women from puberty to menopause.

Body shape, fat distribution, and body composition

At some time in the duration of puberty, and during the increasing levels of female steroid sex hormones that are secreted by the ovary, the lesser half of the pelvic arch and as a result either side of the body below the waist and above the thigh become broader, wider or more extensive (providing a well-built birth passage or tube lined with epithelial cells and conveying a secretion or other substance). In females the fat aggregate of cells changes to a larger proportion of the body structure than in the opposite sex, mainly in the usual woman apportioning of physical structures.

Body odour and acne

Increasing levels of androgenic hormone can change the aliphatic monocarboxylic acids composition of salty fluid secreted by sweat glands, consequential to more body odour in female human. This transformation heightens the vulnerability to inflammatory disease involving the sebaceous glands of the skin during puberty.

Genetic influence and environmental factors

Different studies have discovered direct hereditary consequences to account for the difference in the period of puberty in properly nourished populaces (Treloar, & Martin, 1990). However, the inherited relationship of timing is high between mothers and female offspring.

Researchers have anticipated that premature puberty inception may be due to some hair care creams which contains placenta. The most noticed environmental consequences are that puberty takes place afterwards in offspring brought up at advanced altitudes.

Obesity influence and exercise

Researches carried out by researchers have related untimely corpulency with early start of puberty in girls. They have discovered that obesity is mostly the foundation of breast development in most teenage girls (McKenna, 2007). Consequently, early puberty in females can be an indication of health predicaments. Strict and rigorous exercises have also been proved to lessen the energy existing for the process of generating offspring, thereby slowing puberty.

Physical and mental illness

Serious illness can hold-up puberty in both teenage male and females. Though, mental infirmities take place in puberty, but the brain goes through major development by the secretion of an endocrine gland that is transmitted by the blood to the tissue which can add to mood physical condition in which there is a disturbance of normal functioning during adolescence pubertal age.

Stress and social factors

A number of the comprehended environmental cognitive factors on the regulation of puberty are social and emotional. However, the most important component of an adolescent’s psychological and social aspects of behaviour is the family, and the majority of the social power researched have accounted that the first occurrence of menstruation in a woman may arise earlier in teenage girls from high-stress family circles. On the other hand, the first occurrence of menstruation in a woman may be somewhat soon after a girl matures in an extended family (Lehrer, 1984).

Another restriction of the social study is that almost all of it is related to female adolescence, partially because female puberty needs better physical resources and because it entails a distinctive occurrence (menarche) that makes female puberty greatly easier than male.

Variations of sequence

The sequence of occurrences of pubertal expansion sporadically differs. Research found out that in about 15% of boys and girls, the first pubic hairs can lead, and then followed closely by the breast development in a woman at the beginning of puberty by a few months. Hardly ever, the first occurrence of menstruation in a woman can take place before other notices of puberty in a small number of girls.

Conclusion

In a general conscious awareness, the end of puberty is procreative development. The standardized basis for comparison for determining the end may be different for diverse reasons: realization of the aptitude to reproduce, accomplishment of most complete adult stature.

The centre of attention on the materialization of gender differences at puberty is grounded on the significant study that, at some point in early adolescence, pubertal period is normally a more essential link of behaviour than is sequential age. This finding needs focusing on pubertal growth before age, when considering the appearance of gender differences in risk taking behaviour, indications of depression, body image instability.

Nevertheless, how developmental changes at some stage in puberty enhances or minimizes the risks for youth has been the centre of a number of research groups, on a national scale and internationally. Significantly, the communications between the social world of pubescent and the biology of puberty may be different by gender.

At last, puberty should not be deemed to be the cause of difficulties in adolescent; rather, it is an indicator for the developmental stage that has significant implications for the change from infancy to adulthood.

Reference List

Alsaker, F.D. (1995). Timing of puberty and reactions to pubertal changes. In M. Rutter (ed.), psychosocial disturbances in young people: challenges for prevention (pp.37-82). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Angold, A., and Worthman, C. M. (1993). Puberty onset of gender differences in rates of depression: a developmental, epidemiologic and neuroendocrine perspective. Journal of Affective Disorders, 29, 145-158.

Apter, D (1980). “Serum steroids and pituitary hormones in female puberty: a partly longitudinal study.”. Clinical endocrinology 12 (2): 107–120.

Garn, S. M. (1992). Physical growth and development. In: Friedman SB, Fisher M, Schonberg SK. editors. Comprehensive Adolescent Health Care. St Louis: Quality Medical Publishing;

Hayward, C. (2003). Gender differences at puberty. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jones, K. W. (2006). Smith’s Recognizable Patterns of Human Malformation. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders.

Lehrer, S (1984). “Modern correlates of Freudian psychology. Infant sexuality and the unconscious.”. The American journal of medicine77 (6): 977–80.

Litt, I.F. (1999). Self-assessment of puberty: problems and potential (editorial). Journal of Adolescent Health, 24(3), 157.

MacGillivray, M. H., Morishima, A., Conte, F., Grumbach, M., Smith, E. P. (1998). “Pediatric endocrinology update: an overview. The essential roles of estrogens in pubertal growth, epiphyseal fusion and bone turnover: lessons from mutations in the genes for aromatase and the estrogen receptor.” Hormone research 49 Suppl 1: 2–8.

McKenna, Phil (2007-03-05). “Childhood obesity brings early puberty for girls”. New Scientist. Web.

Nelson, R. J. (2005). Introduction to Behavioral Endocrinology. Massachusetts. Sinauer Associates.

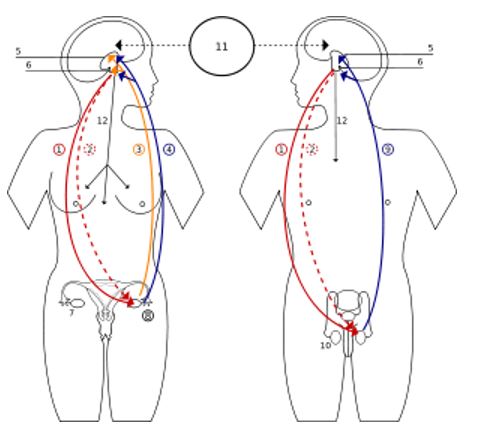

Pubertal diagram. Web.

Siegel, M.J., & Surratt, J.T. (1992). “Pediatric gynecologic imaging.”. Obstetrics and gynecology clinics of North America 19 (1): 103–127.

Tanner, J.M., & Davies, P.S. (1985). “Clinical longitudinal standards for height and height velocity for North American children.”. The Journal of pediatrics 107 (3): 317–329.

Treloar, S. A., & Martin, N. G. (1990). “Age at menarche as a fitness trait: nonadditive genetic variance detected in a large twin sample.”. American journal of human genetics 47 (1): 137–148.

Zuckerman, D. (2009). “Early Puberty in Girls”. National Research Center for Women and Families. Web.