Byzantine art is characterized as “dazzling in its virtuoso techniques and coloristic effects” and the art historians call it “a mirror of the pomp and splendor characteristic of Byzantium’s elaborate ceremonials at court and in church” (Laiou and Marguire 83).

Unfortunately, time is merciless and we have been “robbed” of a considerable portion of the art and culture of Byzantium (Laiou and Marguire 83). However, the extant masterpieces created at the time of the Byzantium Empire can tell contemporary people a lot about social, economical, and political situation in the Empire.

Thus, the works of art present the concept of the emperor as the embodiment of state and divine power, placing him below Christ in the hierarchy of power but above other influential personalities as, for instance, empresses.

Since the predominant themes of art in Byzantium were religious and imperial themes, the importance of the emperor for art is unquestionable. Hoffman states that Byzantine artists expected the emperor “to conform to a number of revered models” and the most important and influential “of the virtuous prototypes was Christ himself” while the emperor’s duty was to imitate Christ on the earth (290).

Since the primary source of divine power is Christ while the emperor is its secular bearer who has God-given right to rule (Kleiner 237), the emperor is depicted in lower status than Christ. Considering the example of the Barberini ivory, Louvre (Figure 1), it is possible to state that it demonstrates the power of the emperor Justinian riding “a rearing horse accompanied by personifications of Victory and Earth” (Kleiner 323).

On the upper panel, Christ is depicted blessing Justinian. Thus, though endowed and led by divine power, Justinian is still depicted in lower status than Christ.

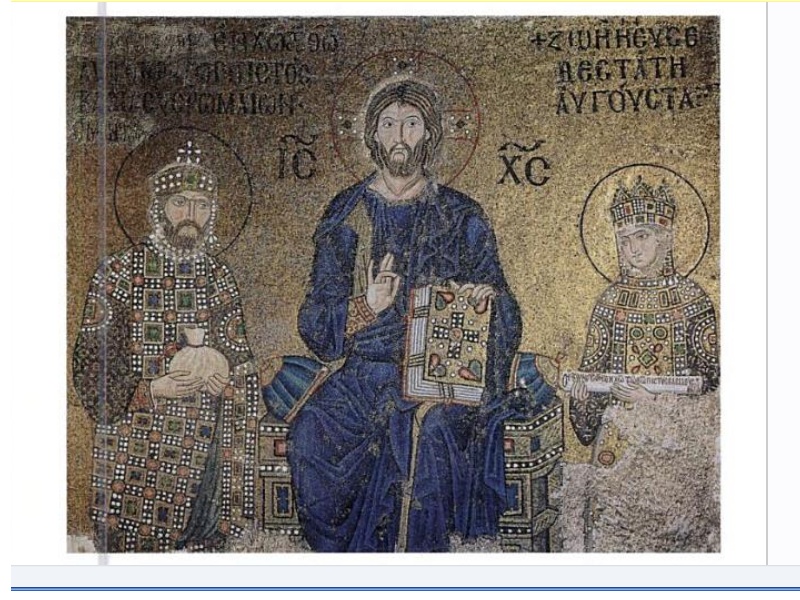

Besides, lower status of the emperor in comparison with Christ can be observed when considering “mosaic panel with Christ, Emperor Constantine IX Monomachos, and Zoe” in St Sophia, Constantinople (Cormack 127) (Figure 2).

The dominance of Christ may be proven by his placing in the center of the mosaic above other figures while the emperor is placed “in pride … at Christ’s right hand holding a purse” (Cormack 128). Thus, the emperor is depicted as the keeper of the wealth of the Empire.

The same mosaic depicts the position of empress in Byzatuim. Zoe, Constantine’s wife, is placed on Christ’s left and she “lower[s] down [more] than her husband” and the empress is holding the document of donation (Cormack 128). This act of lowering symbolizes her inferior position in comparison with the husband.

The mosaic “Theodora and Attendants” in San Vitale, Ravenna, Italy (Figure 3), depicts the empress who is waiting “to follow the emperor’s procession” that also proves her submissiveness to the emperor (Kleiner 240). However, on the whole, empresses also shared high status in art, as Wheeler states, the empress Theodora was a figure “too powerful … for the artist to ignore” (164).

Drawing a conclusion, it is possible to state that the high status of the Byzantine emperor can be easily traced with the help of Byzantine art. Mosaics, ivories and other masterpieces that have remained intact up to the present depict emperors as the embodiment of divine power on earth.

However, Christ is shown as the divinity, blessing the emperors but being ultimately superior to them as Christ is always placed either on the upper panel or in the center of the mosaic. As for empresses, they are recognized as influential figures, but lower than their husbands in the hierarchy of power.

Works Cited

Cormack, Robin. Byzantine Art. NY: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Hoffman, Eva Rose F. Late Antique and Medieval Art of the Mediterranean World. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2007.

Kleiner, Fred S. Gardner’s Art through the Ages: A Global History. USA: Cengage Learning EMEA, 2008.

Kleiner, Fred S. Gardner’s Art through the Ages: The Western Perspective. USA: Cengage Learning, 2009.

Laiou, Angeliki E., and Henry Marguire. Byzantium, a World Civilization. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks, 1992.

Wheeler, Bonnie. Representations of the Feminine in the Middle Ages. Sawston: Boydell & Brewer, 1995.