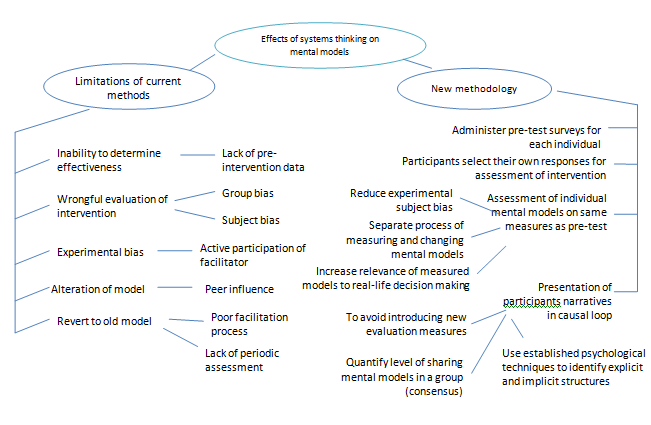

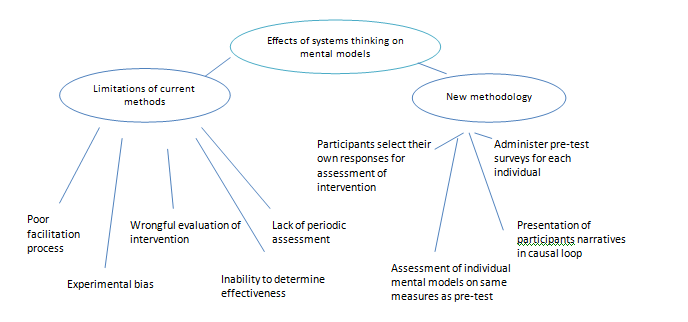

Create one spray diagram to summarize the different ideas of the article respecting the conventions, and techniques

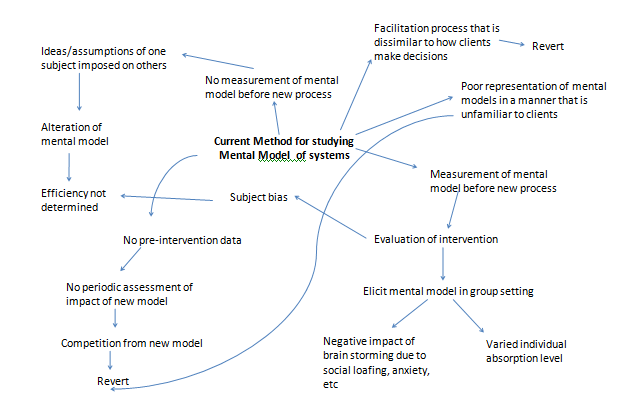

Draw a multiple cause diagram to show all the sources of the Limitations of current Methods for Studying Mental Models of Systems. Reflect on your diagram in no more than 200 words

Some of the limitations with the current study method of the Mental model are caused by the lack of facilitators to measure the present model before implementing the new one. Consequently, there is no way for the facilitators to evaluate the impact of the new model. This causes wrong interventions that may be influenced by a few subjects who impose their ideas and assumptions on other members.

This alters the overall intervention, and its efficiency in that setting cannot be determined. On the other hand, the previous mental process may be evaluated, forming a way for the intervention to be assessed. However, eliciting the mental model based on the views of the group, as opposed to individual perceptions leads to wrongful representation of the impact of the intervention.

On the other hand, the facilitator may influence the opinions of the subjects, leading to subject bias, which poses problems in determining the efficiency of the intervention.

If the individuals administering the intervention use a facilitation process that is unfamiliar with how the clients make their decisions, or use poor representation techniques when introducing the clients to the new mental model, then this increases the chances of the clients reverting to the old model.

Conversely, the lack of periodic assessments of the new model may pose adaptation problems to the clients, causing them to revert to the old model.

Concept of mental models

Mental models reveal and assist individuals in an educational or corporate setting to understand the thought and decision-making process. According to Vosniadou (2002, p. 4) “mental models are analog representations that preserve the structure of the item they represent”.

Mental models reside in the mind of individuals for long periods of time, which poses challenges when introducing new systems. However, Vosniadou claims that most mental models are created on the spot to help individuals cope with the dynamics of the situations that they are facing.

The design process of mental models aims at enhancing the efficiency of individuals when tackling a problem, which enables them to arrive at solution with ease. Vosniadou states “mental models are also constrained by the framework and specific theories within which they are embedded and thus can be valuable sources of information about them” (2002, p.4).

One of the key features of robust mental models is flexibility. Flexibility refers to the ability of a mental model to vary in order to provide individuals with both a positive and negative thought process (Doyle & Ford 1998). Robust models should also lead to selective perception in the decision making process.

This is a necessary aspect of a mental model since it allows the system to reveal core information (Doyle & Ford 1998). Selective perception facilitates filtering of redundant information (WebFinance 2012, p. 1). The third characteristic of a robust mental model is that it should be limited in its scope in order to avoid straining the individual’s memory.

How mental models are central to The Systemic/Holistic Thinking

Positive and high quality system thinking are key attributes for organizations in order to achieve their objectives. This can be achieved through the implementation of mental models. Organizational-positive and high quality system thinking are characterized by consistent, dynamic and complete mental models.

The systematic point of view provided by Doyle and Ford (1998, p. 3) suggests “mental models are the “products” that modelers take from students and clients, disassemble, reconfigure, add to, subtract from and return with value added”.

Mental models provide modelers with a way of measuring the effectiveness of a particular system-thinking-intervention exercise. There are three key features of an effective system intervention exercise. First, it is a technique for eliciting the right mental models. Second, it is a technique for changing mental models.

Third, it is a technique for measuring the change in mental models. Current methods for studying mental models suffer from serious limitations (Doyle 2011, p. 131). According to Doyle, the elicit mental models in use are “substantially different from the mental models that clients actually use to make business decisions” (p. 131).

Limitations of current methods for studying mental models as cited in the article

The inefficiency of the current methods in measuring mental models is mainly due to their primary design function, which is to improve and not to measure mental models (Doyle 2011, p. 129).

The assessment exercise either alters the mental models or is undertaken when the alteration has already occurred. This makes it difficult for modelers to determine the effectiveness of a system-thinking-intervention-exercise since they lack pre-intervention data with which to compare the new data set.

The current methods also lead to reduced effort at the end of the intervention exercise. This is a necessary step that is aimed at gathering evidence that supports the realization of desirable change in mental models (Doyle et al 2011, p.129). Typically, much of the effort in these current methods is skewed towards the beginning of the intervention exercises, whereby it is directed at eliciting the mental models.

The third limitation is due to the disparity in the measurement of the mental models at the beginning and the end of the intervention exercise. This disparity makes it impossible for modelers to determine whether there is actual change in mental models. In addition, modelers cannot detect the implied change due to use of different measurement tools and procedures.

In view of this limitation, it is recommended that, first, the same measurement procedure and instruments be used at the beginning and the end of the intervention exercise, and second, that mental models be elicited again at the end of the intervention exercise instead of asking participants whether or not they perceive any change in their mental models.

Doyle et al (2011, p. 130) claims that inquiring from the subjects about the impact of an intervention enhances the probability of subject-bias since it encourages participants to communicate the true state of affairs and discourages them from giving the answers that the interviewer wants to hear.

Current methods are also ineffective in monitoring the progress of participants when adopting a new mental model (Doyle et al 2011, p. 130). According to cognitive psychology, a new mental model is often in competition with the incumbent and inferior mental model it has set out to replace.

The old mental model is better placed since it has established multiple connections with a participant’s long-term memory (Doyle et al 2011, p.129). The new model can only replace the older mental model entirely if it is used frequently, so that its details are permanently written in the clients’ memory. It is imperative to assess the progress of participants in adopting a new mental model.

This ensures that the adoption process is successful and is not corrupted. Current methods for studying mental models overlook this fact. According to Doyle et al (2011, p.129) the current methods make the assumption “improved, more dynamic mental models facilitated by the system thinking interventions are easily accepted and stable”.

The fifth limitation exhibited by current methods is that they allow eliciting of mental models by participants who are in a group setting (Doyle et al 2011, p. 130). It is mistakenly assumed that there is a shared consensus in a group and that each group member adopts the mental model put forward by the group (Doyle et al 2011, p.129).

Furthermore, psychological studies show that groups facilitate the generation of low quality ideas since they promote social loafing, anxiety and thought process interruptions (Doyle et al 2011, p. 129).

It is advisable that mental models be elicited from individuals when in isolation and not when in a group. This is mainly because in an isolated individual setting, there is no pressure to conform to a collective mental model, and there is a reduced risk of losing valuable information.

Current methods inherently assign facilitators with a problematic role, especially when mental models are being measured (Doyle et al 2011, p.129). Facilitators are required to generate and direct the discussions that elicit mental models. In addition, the current system requires facilitators to summarize the ideas of the subjects that surface.

This arrangement is associated with a high probability of experimenter bias since “the facilitator may inadvertently give the participants clues about what ideas are better than others or lead the discussion in a direction that the participants would not choose on their own” (Doyle et al 2011, p.129).

Furthermore, facilitators may inadvertently loose valuable information or dilute the information they have collected when they determine the lifespan of discussions. Facilitators lose vital information when they end discussions too soon, whereas the latter occurs when they end them too late.

The seventh limitation involves the task assigned to participants. According to Doyle et al (2011, p. 130) these tasks are “often ill-defined and quite different from the way people naturally go about making decisions”.

This technique encourages participants to create on-the-spot mental models instead of encouraging them to elicit the mental models they normally use to make decisions. Such situations arise when modelers change the questions that the participants are asked to monitor the intervention.

The challenge can also be caused by altering the order of questions. Doyle et al (2011, p. 130) points out that “what people remember and think about can be highly dependent on subtle characteristics of the situation they are in at the time and even seemingly inconsequential differences in how questions are worded”.

Hence, it is recommended that participants be subjected to a well formulated decision task that resembles, as much as possible, the one that they encounter on a daily basis.

In addition to the limitations stated above, some current methods also employ intricate communicating techniques when introducing new mental models. Participants are taught using complex techniques that cause them to make numerous errors.

In some instances, these techniques are so complex that they encourage participants to revert to the old techniques for communicating mental models that they were used to. It is, therefore, recommended that the technique for communicating (or expressing) mental models employed in an intervention exercise factor in the manner in which the individuals of interest normally communicate their ideas.

This increases the accuracy of mental model representation and enables modelers, at the end of the intervention exercise, to determine whether there has been any significant progress in changing the mental models of participants.

How mental models can be changed according to the systems thinking approach

Taking these limitations into account Doyle et al (2011 p. 131) proposes a methodology for changing mental models that is based on systems thinking approach. This method is not only effective in changing mental models, but also in measuring the ability of an intervention exercise to change the same.

The new methodology proposes that the intervention exercise should begin with a pretest survey in which participants are asked to explain the cause of a particular pattern of data. At this point, the primary goal of the methodology is to establish the events, factors and variables that caused the pattern. Afterwards, the relationship between them can be determined (Doyle et al 2011, p. 131).

An advantage of this approach is that the participants decide on their own volition, the extent of information to give in their responses. The new methodology also suggests that the intervention exercise ends with a posttest survey, which is conducted in exactly the same manner as the pretest survey.

The advantages of this method include “separation of the processes of changing and measuring mental models, minimizing the potential for the experimenter and subject bias; and increasing the likelihood that the measured models are those that are used in real-life decision making” (Doyle et al 2011, p. 131).

This new model also employs causal loop diagrams technique to represent the participant’s mental models. Participants are supposed to use the techniques they are familiar with to communicate (elicit) their mental models, such as narratives.

Experimenters are then required to code these narratives into the causal loop diagrams. They achieve these using known psychological techniques that are effective in uncovering underlying explicit and implicit structures that are present in narrative text.

Doyle et al (2011, p. 131) states “by identifying the number of subjects who include a variable and counting the number of variables, connections between variables, and feedback relationships, pre-post differences in the content, structure, complexity and dynamics of mental models can be quantified”. This quantification is essential in measuring how effective an intervention is in improving the system thinking of participants.

Conclusion

Mental models are useful tools in aiding us to understand the decision-making process of an individual. They have been and will continue to be central in improving systems thinking in the organization since they provide modelers with a way of getting inside an individual’s mind and tuning it to reason appropriately.

Furthermore with Doyle’s et al’s proposed model, it is possible to measure the effect of a given system intervention exercise on an individual’s mental models (Doyle et al 2011, p. 131). As such, organizations can determine if indeed the system thinking intervention exercises they invest in are worthwhile

Reference List

Doyle, J. K. & Ford, D. N. 1998, Mental models concepts for systems dynamic research. Web.

Doyle, J. K., Radzicki, M. J., & Trees, W. 2011, Measuring the effect of systems thinking interventions on mental models. Web.

Vosiniadou, S. 2002, Mental models in conceptual development. Web.

WebFinance 2012, Selective perception. Web.