Introduction

In economic literature, monetary policy is most often defined as central bank policy. Monetary regulation is one of the elements of the state’s macroeconomic policy. This is a set of short and long-term measures aimed to change the money supply in circulation, the volume of credit, the level of interest rates, and other indicators of the loan capital market. Therefore, the central bank of any state acts as a subject of monetary regulation. It controls money turnover not directly but through monetary and credit systems. By influencing credit institutions, it creates specific conditions for their functioning. In the course of the evolution of the world economy, the central bank has become the prevailing type of monetary authority worldwide. It is the monetary authority with discretionary powers in the area of monetary and exchange rate policy and is also responsible for overseeing the banking sector.

Central banks of developed and developing countries function differently due to their distinctive economic capabilities, availability of free funds, interaction with active market participants, and other criteria. At the same time, some similarities may be observed, for instance, courses to maintain price stability. This work aims to identify the similarities and differences between central banks in developed and developing countries by analyzing relevant data and specific conditions that determine the success and sustainability of their operations.

Reasons for Differentiating the Opportunities of Central Banks

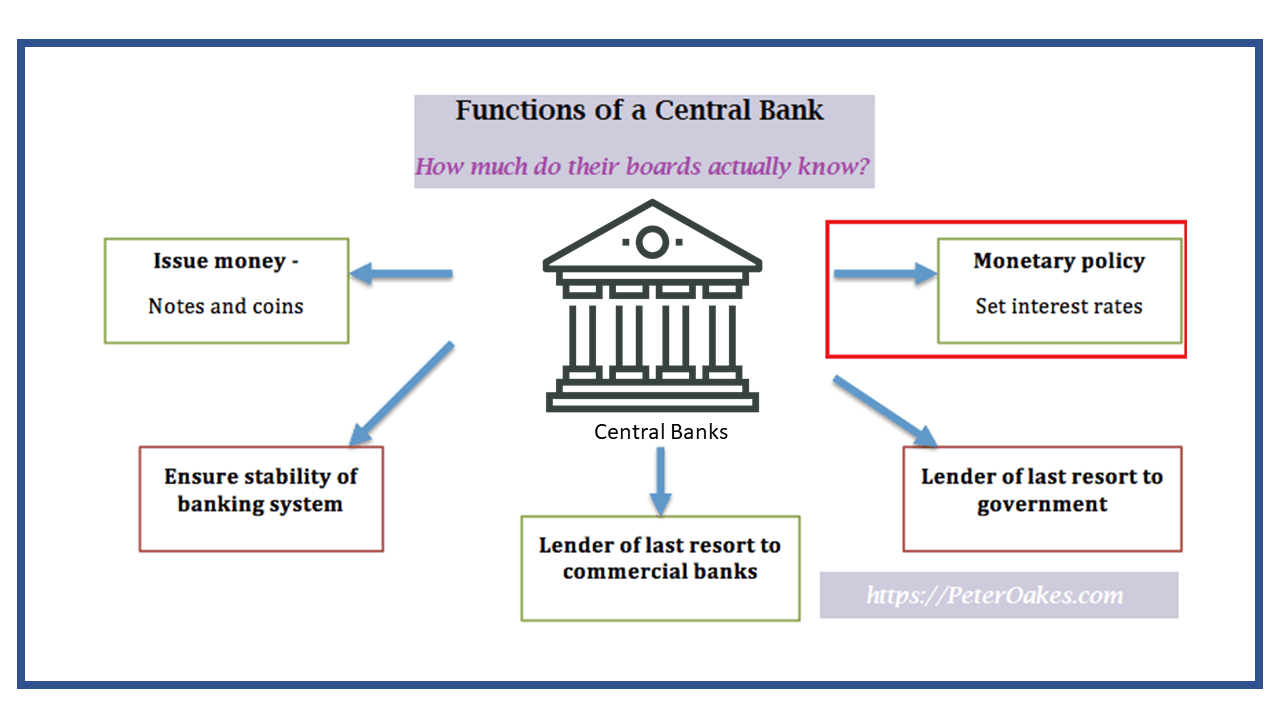

The degree of openness and transparency of central banks depends on each state’s level of economic development and the strategy of monetary policy, and this is politically true for political institutions. Reality shows that developed economies have a higher level of openness and transparency than developing economies (Hughes Hallett and Proske, 2017). Central banks pursue monetary inflation targeting policies with greater transparency than central banks pursuing exchange rate targeting policies. In Figure 1, the main functions of these boards are reflected (Functions of a central bank, 2020). These peculiarities of work are crucial aspects determining the sustainability and effectiveness of central banks.

Central banks occupy a special position in the economy and, for this reason, become the centers of the credit system. They have close ties with governments, advise them, and implement in practice the monetary policies of states. According to the United Nations Environment Programme (2017), this board acts as the banker of the government in the broadest sense of the word. The central bank performs the function of the body of state regulation of the economy. It is empowered to regulate the monetary sphere, keeps official gold and foreign currency reserves, and manage them on behalf of the state (Martínez-Hernández, 2017).

However, central banks of different countries solve their tasks distinctively. The fields of control that differ are the emission of money, the implementation of monetary settlements, performing the role of a financial agent of the treasury, providing loans to the national banking system, and other functions (Vernengo, 2016). The relations between the government and the Ministry of Finance are distinctive. The set of administrative and market methods of regulation in the conduct of credit policy is individual, and the scales and forms of refinancing of commercial banks are unique.

The capital of central banks can have a different form of ownership – state, private (joint-stock), and mixed when the state owns only a part of the bank’s capital. Today, according to Martínez-Hernández (2017), in most countries, this capital is wholly owned by the state. In some states, its shareholders are commercial banks and other financial institutions. Whether the state owns the capital of the central bank or not, there are always close ties between the central bank and the government due to the interests of both sides. Thus, there is a need to compare how such board functions in distinctive economies to find common and distinctive features and highlight the unique peculiarities of the relationship between central banks and financial institutions.

Peculiarities of Central Banks in Developed Countries

In almost all economically developed countries, there are several laws in which the tasks and functions of the central bank, as well as the tools and methods for their implementation, are formulated and fixed. In some states, as Bodea and Hicks (2018) argue, the main task of the central bank is reflected in the constitution. As a rule, the main legal act governing the activities of the national bank is a specific law regulating this board. It determines the bank’s organizational and legal status, the procedure for appointing or electing its senior staff, and its status in relationships with the state and the national banking system. This law establishes the powers of the central bank as the emission center of the country.

Although there are many common points in the banking legislation of different countries, one can find significant differences in the relevant legal acts even among states that are at the same level of economic development. According to Vernengo (2016), the laws on central banks can be differentiated based on the degree of the regulation of this board’s functions. In particular, the topics are raised on how specifically its tasks and the instruments at its disposal are defined. German and Austria can be cited as examples of countries where the legislation on the central bank is most clearly defined (Martínez-Hernández, 2017).

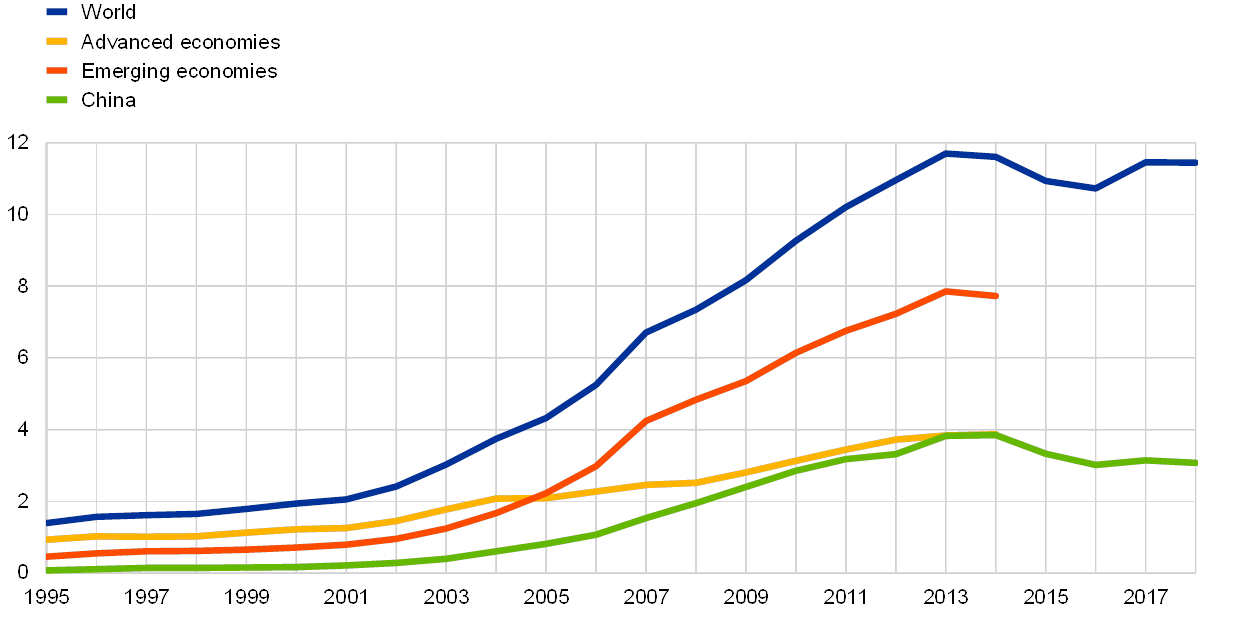

For instance, foreign currency reserves that largely shape the stability of economies are also regulated by these bodies. In Figure 2, the comparison shows how foreign currency reserves are allocated by using the example of advanced and emerging economies, with the Chinese economy as an individual industry (Chiţu, Gomes, and Pauli, 2019). As a result, one of the features of the central banks of developed countries is the presence of a solid legislative framework dictating the functions and powers of this body.

An important condition for the functioning of the central bank in the country’s economy is the degree of consistency of its policy with the economic policy of the government. This implies the principles of interaction of the central bank with the national banking system (United Nations Environment Programme, 2017). The central bank’s policy should be in line with the policy pursued by the government of the country. At the same time, the state cannot have unlimited power. Whether the central bank’s capital is owned by the government or not, this financial board is a legally distinct entity (United Nations Environment Programme, 2017). It disposes of one’s capital as an owner, and its property is separated from the property of the state. A strong economy can allow such independence, and in developed countries, this principle of interaction is clearly expressed in the separation of assets and functions.

As a result, the degree of independence of central banks differs from country to country. According to Martínez-Hernández (2017), in a number of states with strong economies, for instance, the USA, Germany, Switzerland, Sweden, and the Netherlands, central banks are legally accountable to the parliament. It is believed that such banks are more independent and have individual powers. At the same time, the legislation of these countries provides for the reporting of the central bank to the government. Thus, the US Federal Reserve System, which is the central bank of the country, submits to the US Congress a report on its activities twice a year (Jaremski and Wheelock, 2017). According to the European Parliament (2020), the central banks of Germany and Japan send reports to the parliaments of their countries annually. As a result, the considered financial boards in developed countries may be characterized as those with a high degree of reporting.

The banking laws of individual countries also differ in the regulation of the relationship between the central bank and the executive bodies of the government. For instance, in the Law on the German Federal Bank, the provision on the independence of the central bank from the government finds a clear expression (European Parliament, 2020). The independence from the executive branch is characterized by the possibilities of appointing and dismissing the governor, appointing and defining the limits of powers of the Board of Directors, and some other control functions. Therefore, when summarizing the characteristics of central banks in developed countries, one can highlight such distinctive aspects as clear legislative frameworks regarding their work, a high degree of independence, and stable and regular reporting.

Differences between Central Banks in Developing Countries

The economies of developing countries, with all the variety of their features, are characterized by a high dependence on the world market situation and the need to use monetary policy measures to regulate currency rates. According to Dafe (2017), interest rates need to remain high to offset holders of risky currencies, and lower interest rates may lead to capital outflows. Internal vulnerability, high inflation, and an underdeveloped financial market are also the reasons for the low flexibility of interest rate policy, and developing countries may feel “the IMF’s criticism” (Dafe, 2017, p. 321).

Low-interest rates can provoke an escape from the national currency and a spike in the volatility of prices and currency rates in the domestic market. On the one hand, the limited possibilities of applying the interest rate policy presuppose an appeal to non-standard measures. On the other hand, the need for currency targeting in any form reduces central banks’ opportunities to pursue the unconventional monetary policy. As a result, developing countries do not have the same capabilities as developed ones and are forced to adapt to specific conditions, which complicates the free growth of economies.

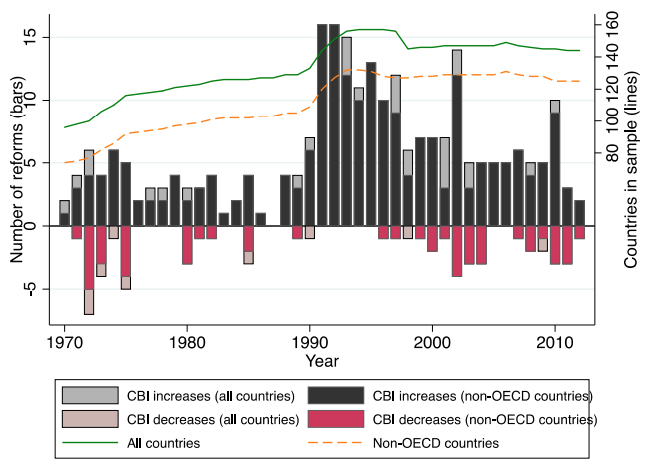

Given this dependence on stronger participants in the global financial market, central banks in developing countries are much less independent. In particular, Masciandaro and Volpicella (2016) note that this criterion correlates directly with the inflation rate and shows that the fewer opportunities central banks have, the higher the risk of inflation. As a result, the distribution of assets is not the prerogative of this body, and the state controls all foreign currency reserve operations, thereby excluding the adoption of non-standard or individual decisions by central banks. Global agencies sometimes offer support for these banks to maintain performance, and in Figure 3, a graph shows how the level of central bank independence (CBI) has evolved over recent years across countries (Garriga and Rodriguez, 2020). However, based on this graph, one can observe that the CBI of non-OECD countries has a tendency to decline, which confirms the idea of insufficient independence of developing countries’ central banks.

The methods of managing the existing assets are a factor that largely distinguishes the central banks of developed countries from those of developing states. While taking into account the fact that in countries with strong economies, special laws exist that determine the measures of operation and control, the gap becomes even wider. The absence of such legislative frameworks in countries with weaker economies makes the management process less regularized. For instance, developed economies actively use balance sheet policies, including quantitative easing, credit easing, and the extended maturity of the central bank’s portfolio (Martínez-Hernández, 2017). Developing economies, in turn, focus on direct instruments, such as lowering reserve requirements, which limits their capabilities and does not allow adopting flexible measures to coordinate development paths.

The intensity of unconventional monetary policy measures in developing countries is significantly lower than in developed countries. In a sustainable financial market, leading central banks are able to apply credit and quantitative easing extensively without fear of inflationary consequences (Dafe, 2017). Developing countries are wary of pursuing loose monetary policies due to potential capital outflows and inflationary implications.

The balance sheets of the central banks of developed countries grow much faster and more successfully than those of the central banks of emerging markets. According to Bodea and Hicks (2018), in developed states, this is due to an increase in credit support measures, quantitative easing, and growth in the reserves of financial institutions. In developing economies, the central banks operate less effectively due to the almost complete absence of credit and quantitative easing. Moreover, in some cases, a decrease in their size is observed due to the depletion of international reserves. As a result, the central banks of developing countries do not feel the need to report regularly since no substantial transactions or operations are conducted. Therefore, in terms of stability, these boards in developed states are more sustainable.

Similarities Between Central Banks in Developed and Developing Countries

Whether the central bank’s capital is owned by the government or not, there should be a clear interaction between them in the conduct of economic policy. The authorities should be interested in the reliability of the bank since it plays a significant role in the implementation of economic policy. In general, Sims and Wu (2021) note that any central bank performs a similar set of functions to its foreign counterparts. The range of tasks and procedures includes issuing banknotes, conducting monetary policy, foreign currency policy, refinancing credit institutions, regulating their activities, that is, banking supervision, acting as a government agent, and many other tasks. Central banks manage the entire credit system of the country, thereby creating a background for cash flows and budget allocation. Therefore, regardless of the stability of the economy or the country’s status, its central bank carries out a certain set of procedures that are invariable and mandatory in any state.

Another similarity between the central banks of developed and developing countries is approximately the same results of policy interventions, which, nonetheless, differ in their scale. As Sims and Wu (2021) argue, the macroeconomic effects of specific optimization measures, for example, strengthening accountability, are directly proportional to the resilience of current banking systems. In other words, the central bank of a developing country can optimize certain aspects of work in the same way as that of a developed country if the right algorithms are applied. For instance, reassigning the bank’s management can bring powerful results and positive implications om the sustainability of current financial policies. Therefore, from the standpoint of organizational aspects, many central banks of different states can operate in a similar way, although the parameters of accountability and independence are distinctive.

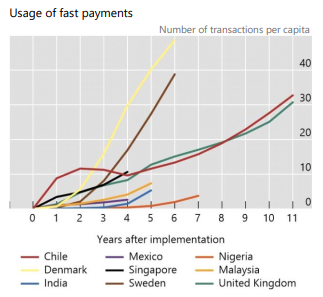

The gradual renewal of the software and technical components of central banks’ work worldwide is a characteristic feature of both developed and developing countries. Despite distinctive performance indicators, the technical optimization of the resource base and operational capabilities is carried out in financial systems globally. For instance, in Figure 4, a graph is presented that reflects the use of fast payments as a technology that has evolved over time (Carstens, 2019). The involvement of countries with growing economies in this process is natural since the dynamics of the world financial market are high. To address the interests of stakeholders, including governments, appropriate innovation is needed. Thus, the gradual optimization of the resource and technical base is a factor that brings the central banks of states with distinctive economies closer and reflects similar trends in the financial market.

In terms of narrower operational specifics, the central banks of developed and developing countries may also share similarities. Despite the distinctive performance and resilience factors, these boards strive to maintain similar goals in their work. According to Bodea and Hicks (2018, p. 362), “credit rating agencies have also explicitly stated that they value the transparency of policies, data reporting, and institutions”. The gradual transition to more advanced management algorithms, the introduction of modern technological innovations, and other interventions bring developed and developing economies closer together and reflect their interests in creating sustainable financial control systems. Thus, the basic transactional and oversight functions, the transition to advanced asset management principles, and the work to optimize internal policies to ensure sustainability are the similarities between central banks in developed and developing countries.

Conclusion

The assessment of the characteristics of central banks in developed and developing countries allows highlighting the common and distinctive features between them and citing specific factors that influence the distinctive management, operational and other practices. High accountability, independence from most oversight bodies, and robust legislation are the features that distinguish the central banks of developed countries from those of developing ones. However, individual factors may be cited as the similarities between these boards. The pursuit of optimization through innovation, promoting identical financial activities, and similar macroeconomic outcomes of interventions are the features that bring central banks of developed and undeveloped countries closer together. Increasing productivity, achieving independence, and strengthening positions in the domestic market are valuable objectives to realize.

References

Bodea, C. and Hicks, R. (2018) ‘Sovereign credit ratings and central banks: why do analysts pay attention to institutions?’, Economics & Politics, 30(3), pp. 340-365.

Carstens, A. (2019)The future of money and the payment system: what role for central banks? Web.

Chiţu, L., Gomes J. and Pauli, R. (2019) Trends in central banks’ foreign currency reserves and the case of the ECB. Web.

Dafe, F. (2017) ‘The politics of finance: how capital sways African central banks’, The Journal of Development Studies, 55(2), pp. 311-327.

European Parliament (2020) Accountability mechanisms of major central banks and possible avenues to improve the ECB’s accountability. Web.

Functions of a central bank (2020). Web.

Garriga, A. C. and Rodriguez, C. M. (2020) ‘More effective than we thought: central bank independence and inflation in developing countries’, Economic Modelling, 85, pp. 87-105.

Hughes Hallett, A. and Proske, L. D. (2017) ‘Conservative central banks: how conservative should a central bank be?’, Scottish Journal of Political Economy, 65(1), pp. 97-104.

Jaremski, M., & Wheelock, D. C. (2017) ‘Banker preferences, interbank connections, and the enduring structure of the Federal Reserve System’, Explorations in Economic History, 66, pp. 21-43.

Martínez-Hernández, F. A. (2017) ‘The political economy of real exchange rate behavior: theory and empirical evidence for developed and developing countries, 1960-2010’, Review of Political Economy, 29(4), pp. 566-596.

Masciandaro, D. and Volpicella, A. (2016) ‘Macro prudential governance and central banks: facts and drivers’, Journal of International Money and Finance, 61, pp. 101-119.

Sims, E. and Wu, J. C. (2021) ‘Evaluating central banks’ tool kit: past, present, and future’, Journal of Monetary Economics, 118, pp. 135-160.

United Nations Environment Programme (2017) On the role of central banks in enhancing green finance. Web.

Vernengo, M. (2016) ‘Kicking away the ladder, too: inside central banks’, Journal of Economic Issues, 50(2), pp. 452-460.