Introduction

Opening: In order to ease off the pandemic, many countries implemented health policies ensure the societies can recover successfully, vaccination became the most efficient and effective tool. Compulsory and voluntary vaccination programs are the current leading tactics. Although voluntary options may not attribute high vaccine uptake rate as compulsory program, compelling strategies may potentially backfire the results such as public anger, distrust and hesitancy (Jennings et al., 2021; Sherman et al., 2020; Motta et al., 2021).Safety concerns also play an important role in public attitude (Neumann-Bohme et al., 2020; Robertson et al., 2021; Kerr et al., 2021; Craig, 2021). Many incentive programs had been promoted but results are not prominent, such as money (Sprengholz et al., 2021), frame (Palm et al., 2021; Davis et al., 2021), social norm (Sinclair &Agerstrom et al., 2021), certificate (Mills &Ruttenauer et al., 2022). This research is going to examine under what circumstancesthe type of vaccination (Savulescu, 2021; Savulescu et al., 2021) will make people hesitate to take the vaccine. Mainly focus on public anger (Graeber et al., 2021; Renstrom& Back, 2021; Abadi et al., 2021; Han et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2020) andidentification to the government.

In order to mitigate the pandemic, numerous governments pursued public health policies for society to recover successfully. Therefore, humanity has observed various development programs launched worldwide to create proven practical, cost-effective vaccines and obtain regulatory approval quickly. It is reasonable to state that the scientific communities have discovered an approach to an impossible mission. Several vaccines have completed trial phases in record time for the first anniversary of the WHO announcement of the COVID-19 pandemic (Anderson et al., 2020). However, this rapid progress has been weighed down by the grave crisis: infodemia in the age of social media. Pseudoscientific misinformation and conspiracy theories have blurred public perceptions of the disease, distorted general understanding of preventive measures, and undermined public attitudes toward vaccination programs.

The success of an immunization campaign relies not solely on the availability and accessibility of vaccines but correspondingly on people’s attitudes. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines vaccine hesitancy as behavior influenced by a set of factors (Cislak et al., 2021). They include mistrust (people do not trust the vaccine, manufacturer, or supplier), complacency (do not see the need for the vaccine), and availability of drugs. The world crisis caused by the coronavirus affects people’s attitudes toward the health care system, science, and medicine in numerous ways. The novelty of the disease and concerns about the safety and efficacy of antivirals have led to many people in the United States stating their reluctance to be vaccinated against COVID-19. This phenomenon is common in other countries: in May 2021, about 25% surveyed stated they would refuse to be vaccinated – they doubted the reliability of the emergency vaccine (Cislak et al., 2021). Italian scientists have also analyzed the concern of hesitancy to immunize during the COVID-19 pandemic.

They searched the PubMed electronic database for original peer-reviewed articles by keyword – their review ended up with 15 studies from the United States, United Kingdom, Turkey, France, Malta, Italy, Canada, Japan, Spain, and Switzerland. The review showed a high overall level of indecision about COVID-19 vaccines. These results are predictable: the number of antivaccers worldwide ranges from 7% to 33% (D’Ancona et al., 2019). According to the analysis, there is a high degree of skepticism about the flu vaccine among African Americans. Unemployed and low-income people rarely agreed to be vaccinated; however, some studies noted that income did not affect attitudes toward vaccination. Moreover, participants with lower levels of education were also less likely to agree to be vaccinated (D’Ancona et al., 2019). There are numerous diverse studies of various populations and reasons for their different attitudes toward immunization. However, no single relevant source analyzes the relationship between anger and individuation on vaccination decisions. Therefore, the correlation of these variables became the central and relevant topic for the thesis.

One of the most prominent aspects of the study is the influence of political beliefs: support for populist parties can be an indirect indicator of hesitancy to vaccinate, at least in Western European countries. Therefore, increasing populist support among the population can be regarded as a threat to public health. Forcing people to be vaccinated has often been a cause of public anger, which has also become a significant issue in today’s world. Therefore, there is a need for a program that will meet the population’s needs and address the high level of anger, which is often caused by the need to obey (Dror et al., 2020). Public anger is an essential variable to identify and influence people’s beliefs. It should be analyzed as an integral part of vaccination programs, which can be changed qualitatively according to the indicators.

Furthermore, coercion is foremost a psychological influence on another person to obey the desired action without informed and deliberate consent. It can include manipulation, threats, blackmail, pressure, and ultimatums (Feng et al., 2018). Altering a person’s feelings and thinking, not just their actions, cannot be attained by violence, which is why coercion causes anger. There must be the person’s desire, interest, involvement, and will in this process. Lately, the fight against the coronavirus epidemic has become identified with the introduction of a more comprehensive regime of QR codes confirming that their owners are inoculated against the SARS-CoV-2 virus (Feng et al., 2018). Having QR codes, a person has rights to move freely around the country and their place of residence. People without QR codes are affected in their freedoms significantly. There are natural ethical questions connected with the admissibility of forcing people to go through the experimental medical procedure. There are also political concerns that widespread opposition to compulsory vaccination, primarily if it affects children, could result in destabilization, taken advantage of by forces hostile to the government and its constitutional order.

Promoting vaccination is a crucial strategy for gaining collective immunity against COVID-19 and a condition for overcoming the pandemic. Advocacy ranges from the mere provision of information to policy prescriptions (Giubilini, 2020). Nevertheless, some degree of autonomous choice is preferable since public health is guided by the principle of the least restrictive alternative. It states that to achieve the general good of collective immunity, people must choose the measures that limit individual rights and freedoms the least (Glenn & Kenney, 2018). The ability to make one’s own decisions and conduct daily life following one’s values and preferences is central to human dignity. Any restrictions on choice lead to agitation, which in turn can affect the vaccination process.

Several COVID-19 vaccines are developed with modern technologies and involve new processes in manufacturing; therefore, some uncertainty surrounds them. Vaccine efficacy is clarified through randomized controlled trials at the approval stage, and then it is refined through field studies (Goralnick et al., 2017). However, mutations in the virus may reduce or influence the effectiveness of the immunization. People have different emotions because this is a very controversial issue and no one can accurately determine the consequences of vaccination for everyone. Therefore, coercion stirs the mind and causes immediate reactions in individuals. Respecting people’s autonomy in deciding is crucial with all the uncertainties surrounding vaccines. Research indicated that some nudges can interfere with autonomous decision-making, cause negative emotions, and force people to make choices they may not want to make (Gualano et al., 2019). While they may quickly lead to desirable results in terms of collective behavior, such interventions may reduce the level of cooperation later. Even though such interventions may promote vaccination now, they may reduce the effectiveness of controlling the spread of other infections and the level of immunization against them in the future.

To maintain social well-being, governments should use nudge-comparison instead of nudge-loss of influence, which emphasizes the negative impact on society of a personal refusal to vaccinate. Moreover, there is a direct link between identification with the government and the stringency of measures. It can be assumed that the higher the credibility is, the easier it is to convince people to get vaccinated. Conversely, where it is low, one must resort to harsher measures. This was the case, for example, in the Congo during the Ebola epidemic in 2018-2019 (Hasan et al., 2021). At the same time, studies confirm that excessive pressure has the opposite effect and undermines the desire to be vaccinated. In the UK, a survey of health and social service workers showed that employer pressure on employees made the latter more likely to refuse vaccination (Hasan et al., 2021). This effect could undermine trust in medicine for years to come – forced vaccination in Africa more than half a century ago still negatively affects health systems. In addition, harsh coercion can undermine trust in the government, and a vicious circle of mistrust and intimidation will emerge. In such a case, bans can only be used as a last resort, but the government should explain why it has decided to use them.

Unity of communication is the key to success: a common stance by doctors, scientists, civil servants, religious leaders, and opinion leaders will influence the general population. Effective persuasion also depends on the speaker’s reputation and credibility (Hosangadi et al., 2020). In the moments of crisis, credibility is made up of transparency, commitment, level of professionalism, and empathy. Withholding information, inconsistent messages from management, and disregard for people’s opinions all reduce people’s willingness to vaccinate. Moreover, group affiliation and general thinking can also have a significant influence on people’s actions and reasoning.

Working in a group, people can make the most unpredictable decisions, and not all of them are rational. A so-called “risk-taking phenomenon” emerges-the tendency to make riskier decisions if responsibility for their consequences is shared with others. Willingness to make risky decisions depends mainly on the individual characteristics of meeting participants and the relationships developed in the group (Krasser, 2021). People present at a meeting may make a difficult decision because no one is personally responsible for it. The process of group decision-making is similar to the operation of individual decision-making. In both cases, the same stages are present – understanding the problem, gathering information, proposing and evaluating alternatives, and choosing one of the alternatives. However, group decision-making is more complex in socio-psychological terms, as each stage is accompanied by an interaction between group members and, accordingly, the clash of different views.

Despite this, it is scientifically proven that belonging to a group directly impacts decision-making. After all, dissent often has negative consequences and can lead to expulsion from the group. For this reason, decisions are more often all taken by consensus, and each particular group shares opinions and views. In the course of numerous studies conducted by followers and social psychologists, it has been revealed that a person often decides based on belonging to a group (Krasser, 2021). In this group, one forms the beliefs, which one does not later abandon. They, in turn, influence the process of decision-making and, consequently, choice.

The essence of the phenomenon of group polarization lies in the fact that in the process of discussion, aimed at working out a decision, significant for the group, a kind of extremization of group opinions occurs. They begin to gravitate to the extreme values of the preference scale, and the number of middle, intermediate decisions significantly decreases. For example, if a group of moderate liberal politicians makes a joint decision, it will be more liberal (Lucia et al., 2021). Conversely, if a group of moderately conservative politicians makes a collective decision, the decision will be more conservative. The primary result of polarization is the following: whatever the initial preference of the group before the discussion, this preference is reinforced during the discussion.

Despite a large amount of research on vaccines, there are still no reliable sources regarding the effects of vaccination programs on the population. Therefore, the purpose of the study is to examine the impact of compulsory and voluntary vaccination programs on vaccine hesitancy. The thesis will focus on the variables of public anger and identity to establish their relationship and influence on people’s choices. Numerous models and calculations will be used so that the truth of the conception can be proven and provide a qualitative basis for further research.

Hypothesis:

- When people negatively identify themselves with the government, compulsory vaccination program increases their anger level.

- When people negatively identify themselves with the government, compulsory vaccination program increases the hesitancy towards the vaccine uptake.

- Compulsory (vs voluntary) vaccination leads to greater anger and hesitation; these effects are reduced for those who identify with the government.

Methods

Participants

Total of 124 participants were recruited via the social media website such as Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp. Of these, 12 responses were excluded from the data due to incomplete responses (7), did not consent (1), did not pass the manipulation check (4). Proceeding with 112 responses, 38 Asian or Asian British (34%), 24 Black, African, Caribbean or Black British (21%), 25 Mixed or Multiple ethnic group (22%), 2 Other ethnic group (2%) and 23 White (21%). Participants aged between 18 and 56 years (M = 28.10, SD = 8.11). This study does not interested in gender difference, thus participants were not required to disclose their gender. Participation was completely voluntary, while participants were incentivised by the opportunity to win a £25 Amazon voucher in a prize draw.

Materials

An online questionnaire was applied in this study, which consists of three scales and a vignette, representing the condition the participants are randomly assigned to. Four major factors were measured, namely the identification level with the government, anger level of the government action and the hesitancy level of vaccine uptake. The questionnaire was developed using an online questionnaire service Qualtrics and there are total of 28 questions developed. The data from the questionnaire were exported from Qualtrics and imported to RStudio for data analysis.

The questions used in this study were adopted from previously established research that generated valid and reliable results. All of the questions were adopted from the original studies, but the wording of the questions were modified to match the current study. This section below provides the adjustment made to the scales.

Identification Scale with the Government: The Identification Scale consists of three questions. All the items are originated from Leach et al. (2008). For instance “I see the government as part of my in-group.”. The Identification scale was measured on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly disagree and 7 = Strongly agree).

Anger Scale: An extensive 18 items Anger scale was derived from the Salzburger State Reactance Scale (SSR Scale) (Sittenthaler et al., 2015), which provided reliable and valid results. The SSR scale is developed based on the nature of reactance, proposed by Dillard and Shen (2005). For example “To what extent do you perceive the reaction of the government as a restriction of freedom?”. The questions were measured on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = Not at all and 7 = Very much).Three items were reversely coded before entering the data analysis process (items 11, 15, 16, Appendix 2).

Hesitancy Scale: There are 8 items in this measurement, which were adopted from Freeman et al. (2021). Although this is a newly developed scale, the scale mostly focuses on the COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK and also generated a good fit of the statistical models. For example “If a COVID vaccine was available at my local pharmacy, I would…”. Hesitancy was measured on a 6-item scale.

Table 1. Question examples for each subscale

The full set of questionnaire questions can be seen in Appendix 1.

Design

The present study used an independent measures questionnaire design. The total of 112 participants were evenly distributed into either compulsory (58) or voluntary (54) vaccination conditions.In data analysis, participants compulsory condition was coded 1, while voluntary condition was coded 0. All participants were required to answer the 3 items Identification scale, 18 items Anger scale and the 7 items Hesitancy scale. To elicit the vaccination program effect, two vignettes were designed to condition either compulsory or voluntary vaccination program. Different wordings were used in each vignette, while the images were kept the same for both conditions in order to reduce confounds.

Procedure

Participants were recruited via different social media website such as Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp. A weblink containing the questionnaire was sent out and the recipients were told that the questionnaire measured their attitude towards vaccination. Participants were required to provide consent to take part in the study once they entered the website. Then they had to complete the three itemsIdentification scale. After that, they were presented the vaccination vignette which was either compulsory or voluntary condition. Followed by the 18 items Anger scale and the 7 items hesitancy scale at the end. Participants were also debriefed with the purpose and the hypothesis of the study, and were reminded that their responses and the email for prize draw were stored separately and anonymously in the University online storage.

Result

Reliability Analysis

High reliability scores are generated from all three scales, Identification Scale α= 0.96, Anger scale α= 0.98and Hesitancy scale α= 0.97. Therefore, all three scales are deemed to be appropriate to treat as three independent variables.

Descriptive Data

Table 2.Descriptive Statistics and Correlations between Study Variables for Overall Sample (N = 112)

Note. *p <.05, **p <.01, ***p <.001

In general, there is a clear difference between compulsory (M = 4.34) and voluntary (M = 2.02) vaccination on vaccine hesitancy. The Pearson’s Correlation plot displays the overview of relationship between each variables. It shows that only vaccination type, anger level and hesitancy level have positive relationship; while Identification has norelationship with vaccination type, anger level and hesitancy level. In terms of the overall performance of allresponses. The mean of 0.52 implies that both conditions were evenly distributed. In the 7-points Identification scale, a mean of 3.7 shows that participants slightly identified with the government. While participants moderately showed anger against the government, with the mean of 4.38 in a 7 points scale. Additionally, a 6 points hesitancy scale gathered a mean of 3.22 which is above the scale mid-point.

Moderation

Table 3. Relationship between compulsion and anger moderated by identification

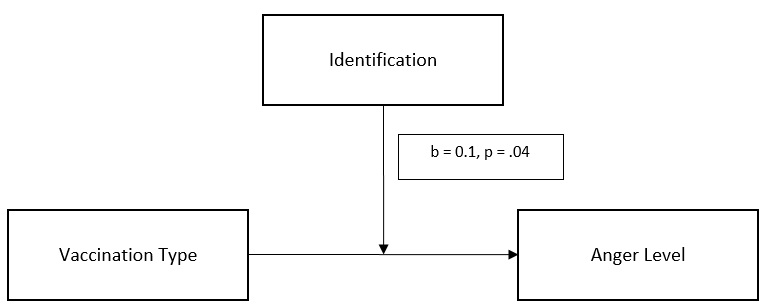

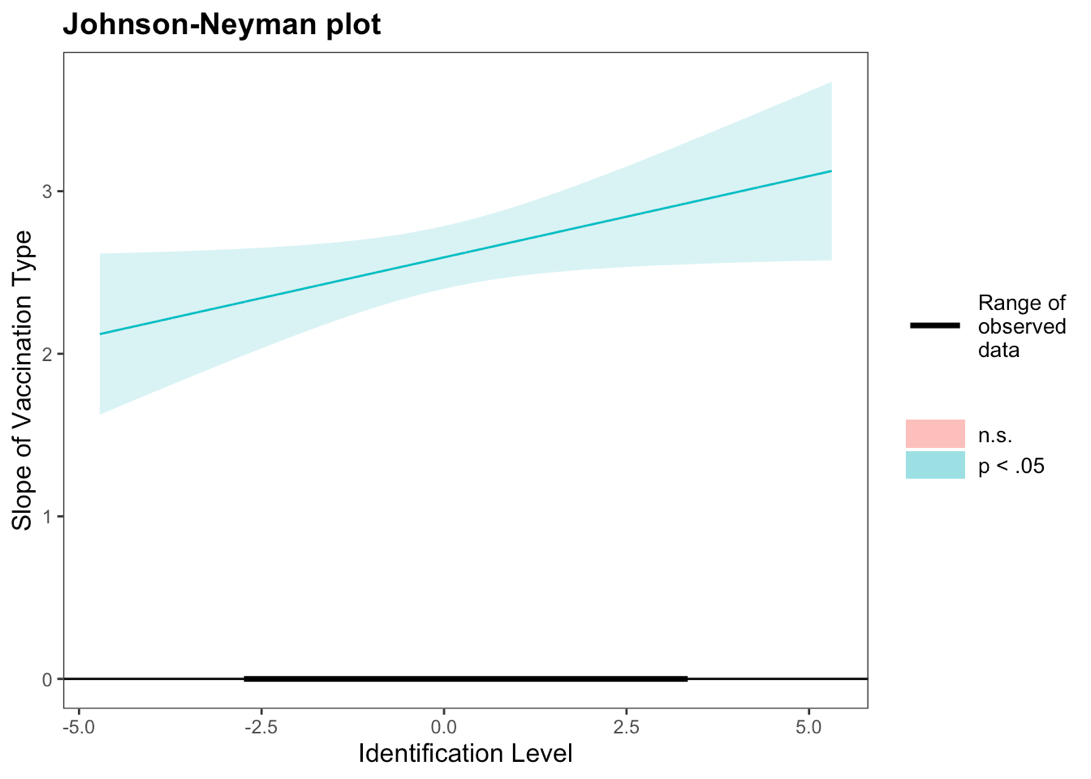

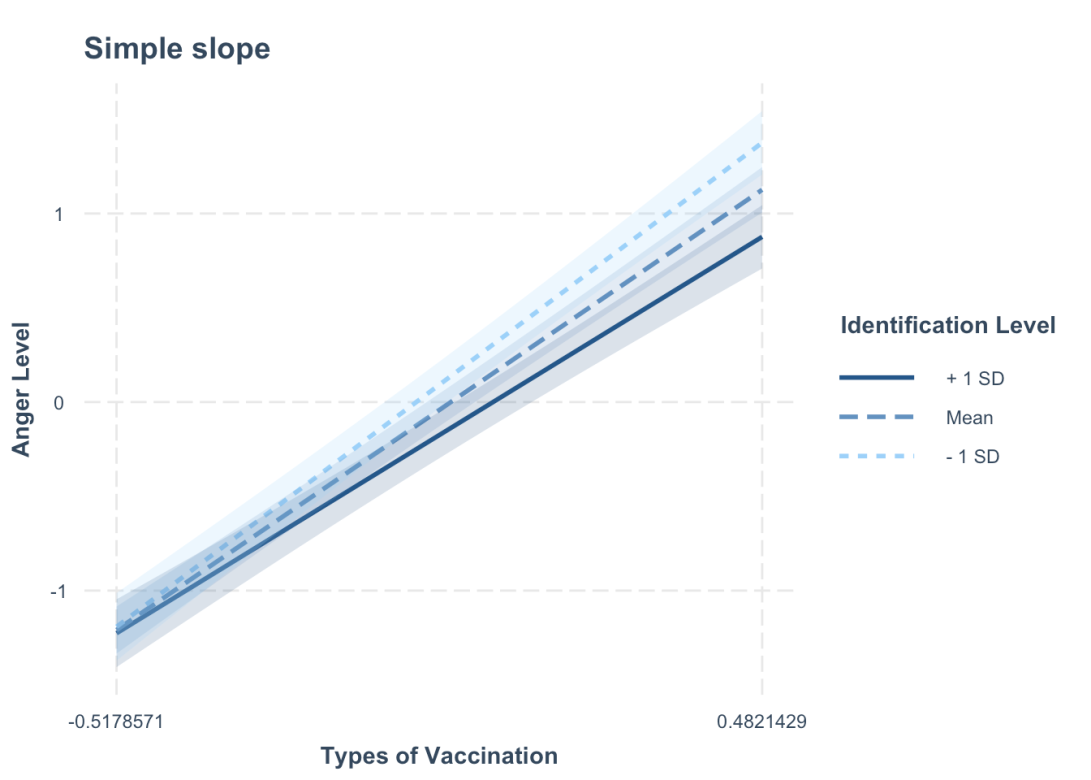

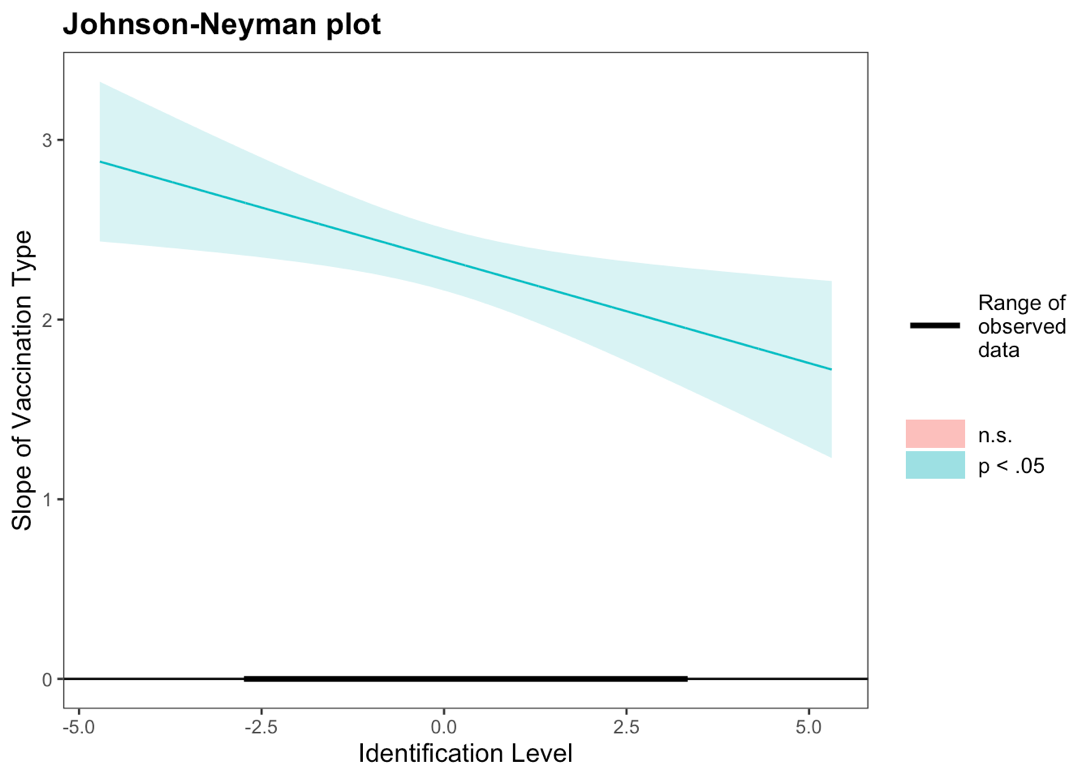

The interactive effect between Vaccination type and Identification issignificant b = 0.1, 95% CI [0.00, 0.20], t = -2.05, p =.04.The confidence interval did not across zero, indicating that the relationship between anger level and the type of vaccination ismoderated byidentification. The positive interaction effect means that anger level increase along with the increase of identification level. When people identify more with the government, they are more agitated when they are forced to get vaccinated. According to the Johnson-Neyman plot, the effect is significant across all different Identification level.In the simple slopes results,lowIdentification level (-1 SD) b = 2.39, t = 17.28, p < 0.01, mean level b = 2.59, t = 26.6, p < 0.01 and high level (+1 SD) b = 2.79, t = 20.19, p < 0.01, the type of vaccination is significantly related to the anger from low to high level.

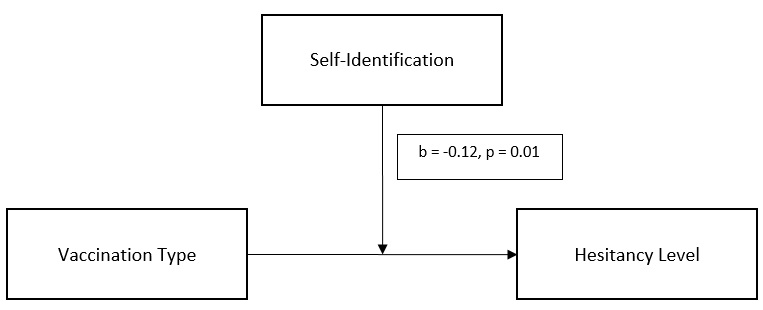

Table 5. Relationship between the type of vaccination and hesitancy moderated by identification

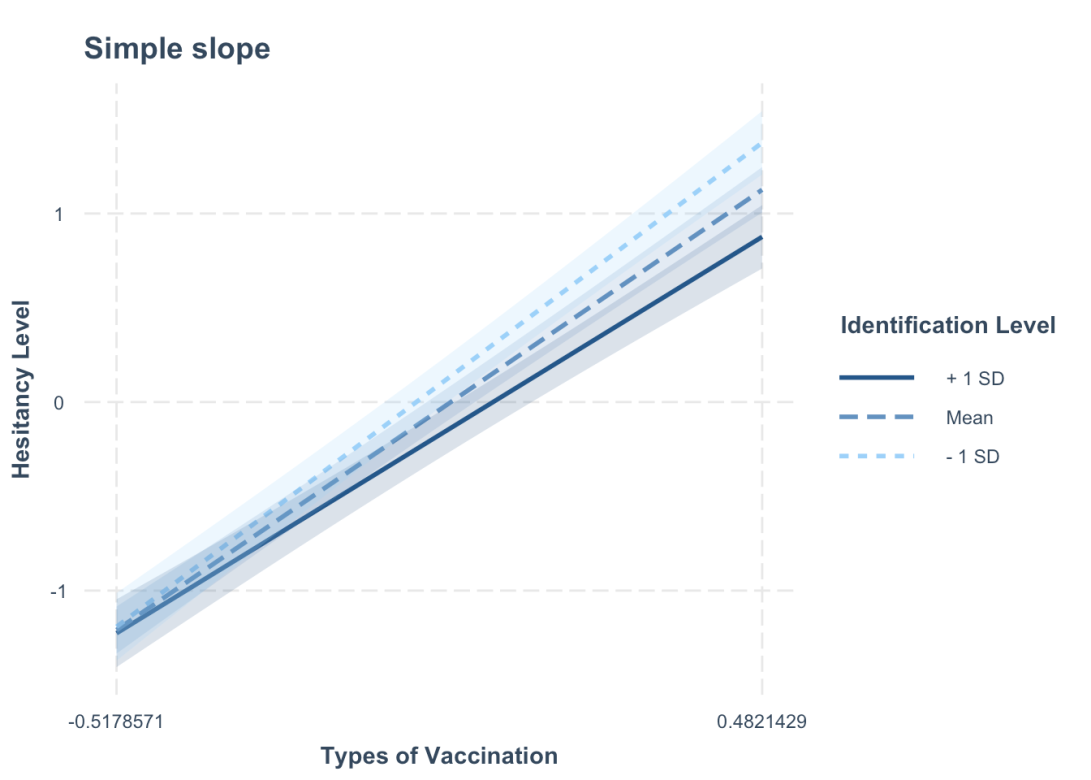

Moderation is shown up by a significant interaction effect b = -0.12, 95% CI [-0.20, -0.03], t = -2.64, p = 0.01, confidence interval does not across zero, indicating that the relationship between hesitancy and the type of vaccination is moderated by identification. Meanwhile the interactive effect is negative, it shows that the hesitancy level increases when theidentification level decreases. In other words, when people are lessidentified with the government, they are more likely to hesitate against vaccination when it is compulsory. The Johnson-Neyman plot showed that the effect is significant across all different Identification level. In the simple slopes results,lowIdentification level (-1 SD) b = 2.57, t = 20.68, p < 0.01, mean level b = 2.33, t = 26.7, p < 0.01 and high level (+1 SD) b = 2.1, t = 16.93, p < 0.01, the type of vaccination is significantly related to the hesitancy from low to high level.

Mediation

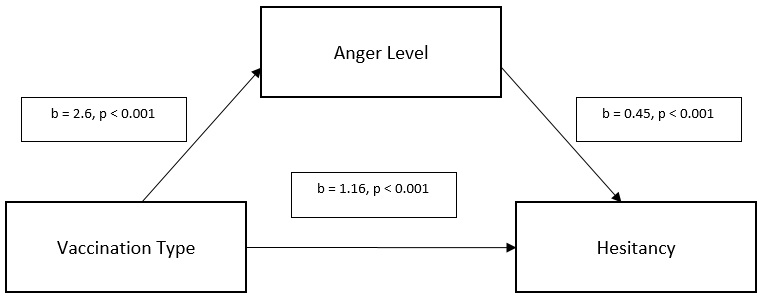

Table 6. Relationship between the type of vaccination and hesitancy mediated by compulsion

In term of the fitting of the model, missing data were handled using maximum likelihood and the number of observations is the same as the number of original observations, thus none were excluded, and bootstrapping was also used. Refers to the mediation equation, the direct effect is b = 1.16, 95% CI [0.77, 1.55], t = 5.87, p < 0.001; the effect of mediator (Anger Level) predicted from predictor (Vaccination Type) is b = 2.60, 95% CI [2.36, 2.82], t = 21.92, p < 0.001; the relationship between the mediator and the outcome (Hesitancy Level) is b = 0.45, 95% CI [0.32, 0.58], t = 6.90, p < 0.001; the total effect of predictor on the outcome is b = 2.33, 95% CI [2.15, 2.52], t = 25.23, p < 0.001; the overall indirect effect of the vaccination type (predictor) on hesitancy (outcome) via the relationship of anger level (mediator) is b = 1.17, 95% CI [0.81, 1.53], t = 6.31, p < 0.001. In general, compulsory vaccination predicts higher vaccine hesitancy because compulsory vaccination predicts increased anger level, which predicts higher hesitancy towards vaccine uptake. Anger level mediates the relationship between vaccination type and hesitancy level, thanks to the significant indirect effect = 1.17, 95% bootstrapped CIs [0.81, 1.53], and which does not includes 0.

Discussion

The purpose of the thesis was to establish the truth of the hypotheses concerning voluntary or compulsory vaccination, considering the variables of anger and identification with the government. A significant finding is that positive identification with the government increases rather than decreases the level of outrage when coercive measures are introduced. Thus, individuals who have experienced high levels of trust in government may lose it or become more hostile toward politicians who campaign against their will. People do not perceive all the government’s actions blindly, even if they have a positive attitude towards it. On the contrary, they perceive the vaccination itself much more harshly than those who did not initially try to trust the government. The second and third hypotheses were confirmed in the course of the study. They suggest that when people identify negatively with the government, a mandatory vaccination program increases hesitancy to use the vaccine. At the same time, the effects of hesitancy decrease for those citizens who identify with the government.

Vaccine safety conveys a lot of public attention, and it has numerous grounds. When situations arise where adverse events are wrongly or adequately attributed to vaccines, they can undermine confidence in vaccines and the official bodies administering them (Machingaidze & Wiysonge, 2021). This can ultimately become a significant cause of numerous public health risks. The results of the vaccination campaign and the rate have failed to stem the spread of the virus, and there have been renewed calls to make vaccination compulsory everywhere (Machingaidze & Wiysonge, 2021). Numerous governments have refrained from this measure on the grounds of respecting the fundamental rights and freedoms of their citizens. However, the attitude toward the COVID-19 vaccine is a particular case: here, the doubts are not due to anti-vaccination sentiments (Machingaidze & Wiysonge, 2021). People most often explain their reluctance to be immunized by the fact that they do not know about the side effects of the vaccine and are unsure of its effectiveness.

COVID-19 vaccination is voluntary in most countries, but in order to influence the category of unvaccinated, some countries have introduced several measures that make life without vaccination uncomfortable. For example, by banning the unvaccinated from public places, requiring them to wear a mask and social distance once these restrictions are lifted for the vaccinated, and introducing quarantines for tourists without vaccination certificates. Several countries have already imposed a mandatory vaccination requirement on specific categories of the population (Murphy et al., 2021). Another incentive could be the threat of losing one’s job. Furthermore, with the introduction of compulsory vaccination coverage, vaccination coverage rose by a third. In the CIS countries, the percentage who had received at least one dose of vaccine increased 1.5-fold to 18% in three weeks by July 6 (Murphy et al., 2021). Mandatory vaccination, including vaccination against COVID-19, can be justified ethically if the threat to public health is significant, confidence in the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine is high, and the expected benefits of mandatory vaccination exceed the alternative solutions.

The population of several countries also supports compulsory vaccination against COVID-19. For example, three-quarters of Australians support introducing such a requirement for workers, students, and travelers. Moreover, the mandatory introduction of vaccination would be supported by half of Belgians, half of the managers of British firms, almost 70% of the Brazilian population, and over 60% of residents of South Korea, Spain, China, and Italy (Puri et al., 2020). At the same time, the study results conclude that there is a clear difference between compulsory and voluntary vaccination in terms of hesitancy to vaccinate. Voluntary vaccination is perceived more acceptably and positively than mandatory immunization.

Therefore, it is conceivable that the administrative costs of coercive influence may be too significant, and it may exacerbate anti-vaccination attitudes. Counterproductive can be another, softer form of persuasion – limiting the access of unvaccinated people to specific activities that are not vital, the researcher adds (Sallam, 2021). This could be perceived as discrimination, especially while the vaccine is difficult to obtain. In addition, such a measure would require a whole list of exemptions and certainly does not promote a positive narrative about the pro-social effects of vaccination.

First, if individuals are convinced that they do not need the vaccine, the need to be vaccinated to continue working will, in some cases, cause them to quit rather than get vaccinated. Second, penalties for violating such requirements, such as fines, hit the least protected and lowest-income populations (Salali & Uysal, 2020). In general, mandatory vaccination predicts greater hesitancy to vaccinate because mandatory vaccination predicts higher levels of anger, which signifies greater reluctance. The level of rage mediates the relationship between the type of vaccination and the level of indecision through a significant indirect effect.

Correspondingly, people’s willingness to be vaccinated is closely related to the level of trust in the authorities. The most painful effect of harsh measures is the reduction of this confidence. Compulsory vaccination signals that the rules do not trust society, provoking a similar reaction (Sasaki et al., 2022). Firstly, the imposition of a requirement for mandatory vaccination induces what is known as psychic reactivity, that is, resistance associated with the individual’s desire to maintain personal freedom of choice. Secondly, such a decision leads to a moral disconnect between the individual and those who force him to take specific actions.

If voluntary vaccination stimulates members of society to unite – many are inclined to show themselves to be responsible citizens in such a situation – then coercion leads to the opposite effect. The third reason is decreased intrinsic motivation: pressure undermines trust in both the authorities and other community members (Sasaki et al., 2022). If the authorities force vaccination, other members of society refuse to be vaccinated, which increases the resistance to vaccination in general. Moreover, this effect also works for law-abiding citizens who plan to be vaccinated voluntarily.

The conducted interviews suggest that people’s reactions to coercion differ depending on their experience of living in a democratic or authoritarian regime. Finding the reason for the rejection of vaccines in a particular country or community would require a careful examination of the local culture and political structure. Still, the main issue in any vaccination campaign is one of trust. A vaccination campaign must be based on trust between those who offer vaccines and those who receive them (Troiano & Nardi, 2021). If it does not, it becomes a struggle, and then it is challenging to keep the spread of the disease under control. In principle, there will always be a proportion of people in society who cannot be convinced to get vaccinated. People need to be motivated to get vaccinated, explain what it gives, what it protects against, and explain what to expect.

Moreover, the type of vaccination, the level of anger, and the level of indecision have a positive relationship. Still, identification has no ties to vaccination type, anger level, and indecisiveness. Vaccination attitudes have a strong influence on vaccination decisions (Sok & Fischer, 2020). Strong attitudes can take over-informed opinion and the decision-making process. They can arise because of a particular identity (religious, anthroposophical, or other), a lack of trust in the appropriate governing bodies, or other factors. Social norms influence individual intentions and attitudes about vaccination in various ways. They subdivide the rules in the group, which determine the position, as they describe how one person should behave or how most people should behave. In this case, a group can be defined by where people live, but it can also be determined by age, gender, socioeconomic status, education, profession, religion, or other beliefs (Sok & Fischer, 2020). That is why a group can be an ethnic group, a specific urban neighborhood, or an online anti-vaccine group.

Both the belief that others think one should be vaccinated and the fact that others are vaccinated can influence your stance on vaccination. Group members tend to conform to the majority position. Thus, when vaccination in a group increases, other members tend to be inclined to get vaccinated. Norms can also be counterproductive, where the social example in a community is not to get immunized (Troiano & Nardi, 2021). Belonging to a group that shares particular religious, educational, philosophical, or other views can also influence one’s stance on vaccination.

When a group’s norms do not support vaccination, its members will refrain from immunization in order to preserve their identity and belonging to the group. Culture influences attitudes and risk awareness in the same way that it influences willingness to participate in community activities (e.g., contributing to collective immunity) and approval of governing bodies. It should be noted that culture is not static; it is pretty fluid. Global networks and global social connections have an enormous impact on culture – it no longer belongs to a specific country. Global online user communities opposed to vaccination are an example of this. Concerns about vaccine safety represent a situation in which adverse events are rightly or wrongly associated with vaccination and create a sense of danger and lack of trust in vaccination and health authorities.

Distrust of vaccination and concerns about vaccine safety are interrelated. When mistrust of vaccines is high, populations are more easily exposed to misperceptions about vaccines. Concerns about vaccine safety in a number of countries have increased distrust of vaccination, as demonstrated by decreased confidence in vaccination and health authorities (Wilson & Wiysonge, 2020). This means that addressing mistrust of vaccination is essential not only to increase vaccination coverage but also to ensure that the public is held firm against concerns about vaccine safety. It also implies that an effective response to vaccine safety concerns can help prevent the escalation of public distrust of vaccination. Coercive measures would temporarily raise the vaccination rate, adding another 10-15% to the current level (Troiano & Nardi, 2021). Simple administrative coercion will save the management system from stupor and the search for complicated moves. However, it will be risky to increase the pressure further because of the Duma campaign, and after the elections, other circumstances may change. Therefore, vaccination is likely to be mandatory but highly inconsistent.

However, sometimes, in the public interest, in the desire of protecting the vast majority of the population, these kinds of decisions can also be generally compulsory. In this case, the balance between voluntariness and obligation can be reversed in favor of commitment. Even though, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), vaccination saves 4 to 5 million lives worldwide each year (Wilson & Wiysonge, 2020). No preventive intervention, including hygiene and sanitation, the use of antibiotics, mammograms, and colonoscopies, has proven as effective in preventing disease as the use of vaccines.

Vaccination, however, requires an earnest collective effort and the close cooperation of citizens with health workers. Nevertheless, many people in today’s world distrust having their health issues handled by the government. When people identify less with the government, they are more likely to hesitate against vaccination when it is mandatory. However, it should be noted that the study may be inaccurate because the efficacy and stimulus of the vaccine are not taken into account.

Different types of vaccines have other effects on the human body, adverse reactions, and hence determination. Considering these indicators together with the study already conducted may be a valid topic for further research. Establishing a correlation between the type of vaccine and its stimuli might show changes in people’s determination in more detail. In this way, an accurate conclusion can be drawn about how voluntary or compulsory vaccination affects choice. It would also be interesting to determine whether the level of anger decreases when vaccinated with a particular type of drug whose effectiveness has been most widely confirmed.

Conclusion

Vaccination is the most reliable way to control infectious disease or weaken its course. It is a typical preventive procedure, a thoroughly controlled process, the reaction to which is comprehended to doctors and is entirely predictable. Nevertheless, the coronavirus infection forced a changed attitude toward vaccination among the population, distrustful of previously untested medicines. It was found that there is a clear difference between compulsory and voluntary vaccination in terms of hesitancy to immunize. Applying a Pearson graph, it was possible to display an overview of the relationship between each variable taken. It demonstrated that only vaccination type, level of anger, and indecisiveness had a positive relationship. On the other hand, identification has no connection with vaccination variety, irritation level, or grade of uncertainty. Moreover, it is revealed that when people identify more with the government, they feel more annoyed when forced to vaccinate. When individuals place less with the government, they are more conceivable to hesitate against vaccination when it is mandatory. Furthermore, compulsory vaccination predicts greater hesitancy to vaccinate because mandatory immunization predicts higher levels of anger.

Everyone should have the freedom to manage his or her own body and health independently. When the state starts to adopt the principle of the forcible provision of a good, it is out of the realm of health care. Suppression, coercion, violence are not about medicine or health, nor about notorious rights and liberties. They raise a question about whether there is the liberty of choice, conscience, and decision-making. The government often stands up for freedom of opinion during the election period, trying to fill the polling stations as much as possible. After all, officials often provide citizens with violent interference with their health. Those measures immediately provoke a reaction of anger, and as the study demonstrated, people who identify with the government have an even more negative perception of coercive measures. Irritation and identification correlate directly with determination about vaccines. Voluntary immunization is sufficiently received by the population and does not contradict the rights of citizens, so it is a program that should be present in every democracy.

References

Anderson, R. M., Vegvari, C., Truscott, J., & Collyer, B. S. (2020). Challenges in creating herd immunity to SARS-CoV-2 infection by mass vaccination. The Lancet, 396(10263), 1614-1616.

Cislak, A., Marchlewska, M., Wojcik, A. D., Śliwiński, K., Molenda, Z., Szczepańska, D., & Cichocka, A. (2021). National narcissism and support for voluntary vaccination policy: The mediating role of vaccination conspiracy beliefs.Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 24(5), 701-719.

Craig, B. M. (2021). United States COVID-19 vaccination preferences (CVP): 2020 hindsight. The Patient-Patient-Centered Outcomes Research, 14(3), 309-318.

D’Ancona, F., D’Amario, C., Maraglino, F., Rezza, G., & Iannazzo, S. (2019). The law on compulsory vaccination in Italy: an update 2 years after the introduction. Eurosurveillance, 24(26), 1900371.

Dillard, J. P., & Shen, L. (2005). On the nature of reactance and its role in persuasive health communication. Communication monographs, 72(2), 144-168.

Dror, A. A., Eisenbach, N., Taiber, S., Morozov, N. G., Mizrachi, M., Zigron, A., & Sela, E. (2020). Vaccine hesitancy: the next challenge in the fight against COVID-19.European journal of epidemiology, 35(8), 775-779.

Freeman, D., Loe, B. S., Chadwick, A., Vaccari, C., Waite, F., Rosebrock, L., & Lambe, S. (2020). COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK: the Oxford coronavirus explanations, attitudes, and narratives survey (Oceans) II. Psychological medicine, 1-15. doi:10.1017/S0033291720005188

Feng, X., Wu, B., & Wang, L. (2018). Voluntary vaccination dilemma with evolving psychological perceptions.Journal of Theoretical Biology, 439, 65-75.

Giubilini, A. (2020). An argument for compulsory vaccination: the taxation analogy. Journal of applied philosophy, 37(3), 446-466.

Glenn, G. M., & Kenney, R. T. (2018). Mass vaccination: solutions in the skin.Mass vaccination: global aspects—progress and obstacles, 247-268.

Goralnick, E., Kaufmann, C., & Gawande, A. A. (2021). Mass-vaccination sites—an essential innovation to curb the Covid-19 pandemic. New England Journal of Medicine, 384(18), 67. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2102535

Gualano, M. R., Olivero, E., Voglino, G., Corezzi, M., Rossello, P., Vicentini, C., & Siliquini, R. (2019). Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs towards compulsory vaccination: a systematic review.Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 15(4), 918-931.

Han, J., Cha, M., & Lee, W. (2020). Anger contributes to the spread of COVID-19 misinformation.Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review, 1(3).

Hasan, T., Beardsley, J., Marais, B. J., Nguyen, T. A., & Fox, G. J. (2021). The implementation of mass-vaccination against SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review of existing strategies and guidelines. Vaccines, 9(4), 326.

Hosangadi, D., Warmbrod, K. L., Martin, E. K., Adalja, A., Cicero, A., Inglesby, T., & Connell, N. (2020). Enabling emergency mass vaccination: innovations in manufacturing and administration during a pandemic. Vaccine, 38(26), 4167. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.04.037

Davis, C. J., Golding, M., & McKay, R. (2021). Efficacy information influences intention to take COVID‐19 vaccine. British Journal of Health Psychology, 2(1), 22-23.

Graeber, D., Schmidt-Petri, C., & Schröder, C. (2021). Attitudes on voluntary and mandatory vaccination against COVID-19: Evidence from Germany. PloS one, 16(5), 23-34.

Jennings, W., Stoker, G., Willis, H., Valgardsson, V., Gaskell, J., Devine, D., & Mills, M. C. (2021). Lack of trust and social media echo chambers predict COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. MedRxiv, 2021-01.

Kerr, J. R., Freeman, A. L., Marteau, T. M., & van der Linden, S. (2021). Effect of information about COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness and side effects on behavioural intentions: two online experiments.Vaccines, 9(4), 379.

Krasser, A. (2021). Compulsory vaccination in a fundamental rights perspective: Lessons from the ECtHR. ICL Journal, 15(2), 207-233.

Leach, C. W., Van Zomeren, M., Zebel, S., Vliek, M. L., Pennekamp, S. F., Doosje, B., & Spears, R. (2008). Group-level self-definition and self-investment: a hierarchical (multicomponent) model of in-group identification.Journal of personality and social psychology, 95(1), 144.

Lucia, V. C., Kelekar, A., & Afonso, N. M. (2021). COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among medical students. Journal of Public Health, 43(3), 445-449.

Machingaidze, S., & Wiysonge, C. S. (2021). Understanding COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy.Nature Medicine, 27(8), 1338-1339.

Mills, M. C., & Rüttenauer, T. (2022). The effect of mandatory COVID-19 certificates on vaccine uptake: synthetic-control modelling of six countries. The Lancet Public Health, 7(1), 15-22.

Motta, M., Sylvester, S., Callaghan, T., & Lunz-Trujillo, K. (2021). Encouraging COVID-19 vaccine uptake through effective health communication. Frontiers in Political Science, 3, 1.

Murphy, J., Vallières, F., Bentall, R. P., Shevlin, M., McBride, O., Hartman, T. K., & Hyland, P. (2021). Psychological characteristics associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance in Ireland and the United Kingdom.Nature communications, 12(1), 1-15.

Neumann-Böhme, S., Varghese, N. E., Sabat, I., Barros, P. P., Brouwer, W., van Exel, J., & Stargardt, T. (2020). Once we have it, will we use it? A European survey on willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19. The European Journal of Health Economics, 21(7), 977-982.

Palm, R., Bolsen, T., & Kingsland, J. T. (2021). The effect of frames on COVID-19 vaccine resistance. Frontiers in Political Science, 3, 41.

Puri, N., Coomes, E. A., Haghbayan, H., & Gunaratne, K. (2020). Social media and vaccine hesitancy: new updates for the era of COVID-19 and globalized infectious diseases. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics, 16(11), 2586-2593.

Renström, E. A., & Bäck, H. (2021). Emotions during the Covid‐19 pandemic: Fear, anxiety, and anger as mediators between threats and policy support and political actions.Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 51(8), 861-877.

Robertson, E., Reeve, K. S., Niedzwiedz, C. L., Moore, J., Blake, M., Green, M., & Benzeval, M. J. (2021). Predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK household longitudinal study.Brain, behavior, and immunity, 94, 41-50.

Sittenthaler, S., Traut-Mattausch, E., Steindl, C., & Jonas, E. (2015). Salzburger state reactance scale (SSR Scale). Zeitschrift für Psychologie.

Savulescu, J. (2021). Good reasons to vaccinate: mandatory or payment for risk?. Journal of medical ethics, 47(2), 78-85.

Sallam, M. (2021). COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy worldwide: a concise systematic review of vaccine acceptance rates.Vaccines, 9(2), 160.

Salali, G. D., & Uysal, M. S. (2020). COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy is associated with beliefs on the origin of the novel coronavirus in the UK and Turkey. Psychological medicine, 1-3. doi:10.1017/S0033291720004067

Sasaki, S., Saito, T., & Ohtake, F. (2022). Nudges for COVID-19 voluntary vaccination: How to explain peer information?Social Science & Medicine, 292, 114561.

Savulescu, J., Giubilini, A., & Danchin, M. (2021). Global ethical considerations regarding mandatory vaccination in children. The Journal of Pediatrics, 231, 10-16.

Sherman, S. M., Smith, L. E., Sim, J., Amlôt, R., Cutts, M., Dasch, H., & Sevdalis, N. (2021). COVID-19 vaccination intention in the UK: results from the COVID-19 vaccination acceptability study (CoVAccS), a nationally representative cross-sectional survey. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics, 17(6), 1612-1621.

Sinclair, S., & Agerström, J. (2021). Do social norms influence young people’s willingness to take the COVID-19 vaccine?. Health Communication, 1-8.

Smith, L. E., Duffy, B., Moxham-Hall, V., Strang, L., Wessely, S., & Rubin, G. J. (2021). Anger and confrontation during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national cross-sectional survey in the UK. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 114(2), 77-90. doi: 10.1177/0141076820962068

Sok, J., & Fischer, E. A. (2020). Farmers’ heterogeneous motives, voluntary vaccination and disease spread: an agent-based model.European Review of Agricultural Economics, 47(3), 1201-1222.

Sprengholz, P., Eitze, S., Felgendreff, L., Korn, L., & Betsch, C. (2021). Money is not everything: experimental evidence that payments do not increase willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19. Journal of Medical Ethics, 47(8), 547-548.

Troiano, G., & Nardi, A. (2021). Vaccine hesitancy in the era of COVID-19. Public health, 194, 245-251.

Wilson, S. L., & Wiysonge, C. (2020). Social media and vaccine hesitancy. BMJ Global Health, 5(10), 4206-4209.