Abstract

This study investigates poverty in urban Brunei, specifically the famous cultural heritage site within the city center, Kampong Ayer. While Kampong Ayer was an impressive city and center of trade in the 15th century, it had deteriorated into a fishing village in the 20th century. Today, due to developments and resettlements aided by the discovery of oil and gas, only 5% of the country’s population live in Kampong Ayer, with the majority coming from lower-income families (Noor Hasharina Hassan & Yong, 2019).

For this study, a qualitative approach was employed with four families interviewed using semi-structured interviews with observations on the condition of their livelihoods and houses. Findings show that many of the families do not earn enough to meet their basic needs, even with welfare provisions from the government. Nevertheless, they prioritize their children’s education first by consuming and spending on things required for their schooling. Despite such effort, these families, including the children, still struggle to attain success.

Part of the reason is likely malnutrition that results from the eating or consumption patterns of the families and also dependency on the children to help out with the family or house chores. Poor academic achievements may result in a lack of capability and level of competitiveness for employment to remove themselves from the vicious cycle of poverty (Gweshengwe & Noor Hasharina Hassan, 2019). Thus addressing this issue will facilitate the government’s drive to achieve zero poverty.

Background on Brunei Darussalam

Brunei Darussalam, usually shortened to Brunei, is a wealthy nation due to its abundant natural resources, particularly oil and gas, with a gross domestic product (GDP) per capita of US$ 31,628.30 in 2018 according to the World Bank (n.d.). Despite Brunei’s high GDP per capita, income is unevenly distributed among its people, as its Minister of Culture, Youth, and Sports, Brunei Darussalam reported in the 14th Legislative Council Meeting, with 5,472 families consisting of 27,360 people reported to be poor (Ministry of Culture, Youth & Sports, Brunei Darussalam, 2011) which is about 6.9% (based on 2011 population figure) despite not having a poverty line in the country. Marginalized urban communities are in danger of slipping through the cracks of governmental policy.

The sultanate has instituted various policies to support its citizens through various ministries such as the Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sports (MCYS) and the Ministry of Religious Affairs (MoRA). However, so far, they have been less effective or sustainable than desired. The government has set the goal of reaching a zero poverty rate by 2035 and continues to introduce initiatives that are more aggressive to help the population improve their income and the quality of their lifestyle. With its wealth and relatively small population, Brunei should have enough resources to succeed in this initiative. However, this assertion only holds if the measures that are implemented address concerns that are relevant to the population.

International organizations, such as UNICEF and the World Bank, have conducted extensive research into the nature of poverty and developed metrics to report the poverty of individual nations. In the past, Brunei has instituted policies to combat poverty that were based on such findings and employed a general theory of poverty. However, these efforts, which apply a “one size fits all” approach, have ultimately been ineffective because they lack an understanding of poverty within the local context in sufficient detail (Gweshengwe & Noor Hasharina Hassan, 2019).

The meaning of poverty and conditions of poverty will vary geographically and temporarily. For example, Brunei is a welfare state. It provides welfare provisions including subsidized education, health services, electricity and water, allowances for the poor and old age, free or subsidized housing, and others (Noor Hasharina Hassan, 2017). This study will examine the poor in Kampong Ayer, an area in Brunei’s capital, Bandar Seri Begawan, and a well-publicized and known cultural heritage tourism site. This paper aims to explore the consumption and identity of some of the low-income families in Kampong Ayer, Brunei Darussalam, in particular, and identify the children’s educational needs. The objectives of this study are as follows:

- To identify the characteristics and causes of poverty in Kampong Ayer;

- To examine income and sources of funding;

- To investigate the consumption patterns and education priorities of children.

Literature Review

General Metrics

Various countries worldwide are becoming concerned with income inequality and the high rates of poverty that emerge when it escalates to extremely high rates. Banerjee, Benabou, and Mookherjee (2006) claim that many developed Western countries relied on the now questionable Kuznets curve, which claimed that as a country grew, income inequality would increase before falling sharply. Pioneered in the middle of the 20th century, the model was true to reality until the characteristic rebounded and began increasing again. As a result, wealthy countries, such as the United States, now have excessively high inequality rates (Osberg, 2017). They also have some poverty issues, though their overall wealth may be mitigating part of that problem. However, the exact state of these countries is not as important as the implications of the failure of their model.

The measures used by entities such as the World Bank are derived from the findings of past economists, many of whom have been influenced by Western schools of thought. Their models, while perhaps appropriate to the time and environment of their introduction, do not necessarily apply nowadays. Gheshengwe (2019) argues that the Income Poverty Line and the Global Multidimensional Poverty Index, two often-used measures of the characteristic, are flawed because they ignore many details that define it. Moreover, Hickel (2016) claims that the United Nations have intentionally manipulated data on their Millennium Development Goals to create a falsely optimistic narrative. He argues that instead of trying to do productive work to eliminate poverty, they redefine it so that fewer people qualify. The validity of the idea requires additional research, but the fact that these studies highlight potential issues in international guidelines is sufficient for this study.

The metrics used by entities such as the World Bank are not necessarily accurate to reality, either. Prydz, Jolliffe, Lakner, Mahler, and Sangraula (2019) admit that the entity’s data is mostly based on projections based on past information, as only 65 out of over 1800 sources that were used for the 2015 global poverty line estimation were from that year. The organization took measures to try and approximate reality as closely as possible, but there is still cause for concern. Moreover, the organization cannot be used as a reliable source of warnings regarding rising poverty rates. The poverty map provided by World Bank (2018) lists Brunei as a country whose poverty levels are unknown, but the report does not demonstrate significant concern over the nation. Whether Brunei does not provide it with relevant information, or the Bank does not investigate it as a non-issue, the country will have to recognize issues and deal with them internally.

There are two potential reasons why the measurements performed by the World Bank and other international organizations would not be valuable beyond being tools for international comparisons. One, identified by World Bank (2016) itself, is that it relies on broad characteristics such as CPI because of the time and cost involved in conducting regular surveys. The metric introduces potential biases and can be inaccurate depending on how countries construct their price indices. Another, as highlighted by Bach and Morgan, is that the United Nations and its associated agencies are beginning to focus on matters such as environment rather than poverty. As a result, they will be devoting fewer resources to investigating it, hoping to eliminate the issue as a part of a more comprehensive approach to improve people’s lives.

Brunei’s Poverty Reduction Efforts

Brunei’s initiative to help its population escape poverty is partly humanitarian in nature, but it is also motivated by other concerns. The oil and gas that have created Brunei’s wealth are non-renewable resources that will eventually run out. As such, the country has to focus on enabling development after its oil money runs out. Dayley (2020) claims that this event will happen by 2040 and that before then, Brunei will have to diversify its economy, a task at which it has so far failed. A possible reason is its unique status of wealth with a significant poor population and the differences between growth factors for low-and-high income status (Bulman, Eden, & Nguyen, 2016). However, another significant reason is that Brunei’s population struggles to support the advanced and high-technology industries that can maintain its wealth despite the small population size in the long term.

As a developing nation, Brunei has to consider the broader picture and observe smaller-scale details with extreme care. For example, Neumayer and Plumper (2016) find an association between income inequality and longevity. While the improvement of the life expectancy of a nation’s citizens is a highly important task in every nation, there are additional reasons why it is particularly crucial for Brunei. Bucci, Prettner, and Prskawetz (2019) identify a possibility that life expectancy can be the determinant in a country’s final state as wealthy and highly developed or deteriorated. If the nation addresses the matter inappropriately, it will struggle to grow and require a robust effort to correct its trajectory. However, as it has a 2040 deadline, there may not be enough time to correct its course to establish a system for maintaining its wealth while the oil on which it depends is still available.

There is a significant disparity in the jobs available to the people of Brunei based on the quality of their education, which may contribute to the inability of people to escape poverty. Cleary and Wong (2016) claim that the country has a case of the Dutch disease, where government-owned oil companies have inflated the public sector to a degree where private enterprises struggle to compete. However, Cobbinah, Erdiaw-Kwasie, and Amoateng (2015) state that poverty has consistently been a significant inhibiting factor for developing countries. With that said, Sehrawat and Giri (2016) note that economic development correlates with poverty reduction. These findings imply that by finding a solution for the issue, Brunei can achieve a synergistic effect, where its growth and poverty reduction supported each other in turn. The question is how this solution may be developed based on the nation’s unique experience.

Concerning Brunei’s future growth, children are particularly important, as they will enter the workforce in the future. Chaudry and Wimer (2016) highlight how poverty and low income, in general, cause children to perform worse than their peers. One of the reasons is that, as described by Halim, Wahyudi, and Prasetyo (2015), low-income families respond to rising food prices by choosing to eat less, potentially leading to malnutrition. Malik, Hazli, and Whitney (2015) also find that, even though such households focus on high-energy food to the detriment of balanced diets, they often consume less than the recommended amount of calories. As a result, children who are expected to guarantee stability and growth for Brunei’s future are not developing adequately and may not succeed at their task. Children are a critical group for poverty elimination, and it is critical to understand their situation and the measures that can be used to help them.

The Poverty Situation in Brunei

Along with Singapore, Brunei is an outlier in its region, likely due to the wealth that each country was able to generate compared to its neighbors. According to Renwick (2011), both countries held high ranks in the Human Development Index in 2011, though they also refused to provide poverty line information and, in Brunei’s case, inequality statistics. The behavior is noteworthy, as the nation collects this information regularly and analyzes it. The report by the Department of Statistics and the Department of Economic Planning and Development (2018) demonstrates a significant shift toward higher incomes between 2005 and 2015. However, it should be noted that the bottom 9.7% of households have slightly higher average expenditures than income.

While the average incomes of most population categories are close to their expenditures or higher than them, there is a noteworthy factor in the report that warrants consideration. Department of Statistics and the Department of Economic Planning and Development (2018) statistics show that nearly a quarter of the average income in the bottom quintile of population is transfer income, which others also receive. This figure is likely to be welfare, which is so widespread in the nation that many no longer consider receiving it as an indicator of poverty (Gweshengwe, Noor Hasharina Hassan, & Hairuni Mohamed Ali Maricar, 2020). However, according to Rose Abdullah (2012), extensive welfare tends to create chronic dependency instead of motivating people to start working. Moreover, these levels of welfare are only sustainable while the nation is wealthy and cannot be considered a viable solution to the problem if they do not lead recipients to become self-reliant.

The income-based metric is not the only measure that can be used to determine whether someone is living in poverty. Gheshengwe and Noor Hasharina Hassan (2019) describe three different views on the matter: income, basic needs, and capability, recommending the third one. Income metrics fail to acknowledge differences in populations and situations, and basic needs metrics disregard the person’s quality of life as long as they can survive. On the other hand, capability metrics create policies that enable people to achieve their aspirations if they put in the effort. When viewed in this light, poverty has severe implications, as, according to Hair, Hanson, Wolfe, and Pollak (2015), it can hurt children’s academic achievements and, hence, their success in life. If not viewed through the capability lens, poverty can become self-perpetuating and ruin the lives of generations of people permanently.

Single Motherhood and Poverty

The existence of single mothers is a particularly prevalent obstacle to Brunei’s mission of eradicating poverty. Gordon, Nandy, Pantazis, Townsend, and Pemberton (2003) identify them as the target of a disproportionate burden alongside some other categories such as senior citizens and people with disabilities. Single mothers are often paid low wages, likely due to their low qualifications and the emphasis on physical labor in jobs with lax requirements. Few to no countries worldwide, regardless of their wealth, have been able to resolve the issue of single motherhood and poverty. According to Brando and Schweiger (2019), in wealthy developed Western nations, women almost always keep the child in separations and are three to six times as likely to live in poverty as those in two-parent households. As such, the task of addressing this issue is likely going to be extremely challenging.

Single-parent families are naturally more inclined to be poor than two-parent ones because they can only use one source of income. According to Bradshaw et al. (2012), this trait leads to higher income instability, particularly for young mothers, which can lead them to struggle to meet their needs. It should be noted, however, that the same consideration can be applied to males, as well. Chant (2007) concludes that single women can raise their children to achieve outcomes comparable to those of two-parent families, while males often cannot, though the study was limited to societies with high single motherhood rates. This tendency can imply underlying issues that would lead the researcher to confound the results, but the finding still warrants consideration. It suggests that single motherhood is not a negative influence if the mother has enough resources.

With that said, when single mothers do reach that financial condition, they tend to struggle to leave it while also raising their child. McKeown and Sweeney (2001) note that the US and UK are concerned because of findings that single-mother households were increasing in number and remained reliant on welfare for extended periods. In a country with a robust welfare system, such as Brunei, such a tendency is also likely to surface, impeding the progress toward its goal. Concerns over the development of children in such households, as described above, are also appropriate. It should be noted that Hamilton and Catterall (2007) find that mothers would often sacrifice their needs to ensure that their children are satisfied. Regardless, their resources are limited in conditions of poverty, and they may not necessarily know how to recognize or prevent malnutrition that stunts children’s growth.

Methodology

Poverty is a complex phenomenon that can be the result of any of a large number of reasons, whether combined or otherwise. As such, the author chose to use interpretative methods to conduct the research. It aims to determine why people are in poverty or remain there for extended periods by analyzing their perceptions and overall circumstances. The study will be qualitative because of its nature as an initial inquiry into the generally underexplored background of poverty in Brunei. There is not enough knowledge to say definitively which factors are relevant in the situation and which are not. First, research into what influences there are is required to identify the principal causes. Quantitative investigations can follow later, based on the findings of qualitative works and covering a more extensive section of the population.

In terms of structure, the study will use the exploratory approach to define the problem and identify its various aspects. It focuses on the present, though it considers the participants’ past if necessary. It also takes advantage of the strengths of the qualitative approach, such as its flexibility and freedom of analysis. As a result, it is highly suitable for the goal of this paper, which makes it overall the best method for the task. The author used two methods to collect information for the paper: semi-structured interviews and observation. Throughout the first approach, they collected specific information throughout a lengthy conversation with a participant and their spouse. The goal of the observation was to analyze the conditions at the participants’ houses and obtain an overview of their overall state and the significant issues that affect them.

The study will use content analysis to derive useful information from the data collected throughout its progress. They can then discuss shared trends as well as differences between situations and the reasons behind them. The observations can highlight the housing concerns of the population in question, which are often not considered in welfare payouts. While the work to address poverty can take a long time because of the scale of the endeavor, unstable housing is an immediate concern. The author chose the Kampong Ayer area for their study for a variety of reasons. The villages on Kampong Ayer are known for their potentially volatile wooden constructions on the water, with many homes having no direct land access. Moreover, the rural environment can provide some perspective on poverty in older areas of Brunei, as opposed to modernized urban ones that may have higher living standards.

The author has chosen four families for the investigation and interviewed the mother in each of them, with the husband being present in one case. The BANTU Services agency, which works with people in poverty and provides them with assistance and jobs, facilitated the researcher’s access to these people. The reason why the author has not covered more cases is partly time constraints and willingness of the informant or participant to be interviewed. Each participant required a significant amount of work to be devoted to them. The limitations of the research warrant a mention, as they may have a significant adverse effect on the findings. The foremost issue is the small sample size, which makes unintentional misrepresentation more likely. Another potential issue is bias on the side of the researcher, who will be gathering and examining information under the influence of their perceptions and beliefs. The author has tried to recognize and eliminate as many concerns as possible and adhered to ethical requirements.

Findings

This section will report on the findings from the interview as well as observations and will be categorized into several sub-sections:

Family Identity: Characteristics and Employment

One prominent theme across each family interviewed in the study is that they have six to seven children per family, at least one of which is a dependent. Out of the twenty-six children (some of whom are adults) in the study, eighteen did not have a job at the time of the conversation, though some were on the waiting list for a job, and others were waiting for their O-level certification. Those who work try to help the family, both monetarily and by buying household needs, but their low and sometimes inconsistent salaries limit their contributions. A few of these working offspring were employed as security personnel or shop assistants. The needs of younger children may not be met, especially in families with lower incomes. However, the families try to keep their children’s best interests in mind, encouraging them to complete their education and move on to a college if possible. They do not mention the reason why education is necessary; in the case of the second family, a family’s son disagrees with his mother regarding the need to complete his education.

Only one of the four women (a few of the women are the household leader as they have separated from their husbands) interviewed in the study holds a full-time job as a phone operator as well as a cleaner, and another works part-time as a masseuse but considers herself incapable of holding a full-time occupation due to health concerns. The three who do not hold a full position also claim that they have not worked for a long time, if ever. One claims that she worked before marriage: “My husband pressured me to stop working but I do not know what his motive is.” The single mothers do not mention receiving any financial assistance from their former husbands, implying no help is given by their estranged or previous husband. As such, they are dependent on their adult or older children and the income that they earn for the family’s day-to-day survival. All of the women receive welfare from several sources.

One prominent theme that emerges throughout the interviews is that the family members who work tend to get low wages. The salaries listed in the interview tend to be in the B$ 300-450 a month, which is close to the total amount majority of the families get in the form of welfare before housing aid, irregular payments, coupons, and other forms of help are accounted for. The total incomes of the families are low, with large numbers of children. Unfortunately, due to the financial desperation at home to sustain the family, the adult children appear to believe that getting a job, especially a government job, is more important than completing their studies despite the grades they attain: “I can just be a military officer, Ma’. Because he got 8 O’s” (speaking of a son in family 2). He was ready to drop his studies to apply for the position of a pilot. Other participants also noted that their children wanted to join the military, and one person studied at a police academy before dropping out for family reasons.

Financial Support from Government and Private Agencies

All of the families interviewed but the third received monetary assistance from one of two organizations: the Baitulmal and JAPEM (The Baitulmal oversees the distribution of zakat, and JAPEM provides various forms of welfare to the poor). They provide many different kinds of help, including assistance for children under 18, housing aid, and others. The former provided B$ 400 per month, and the latter gave the family B$ 260. The third family, which did not receive welfare payments, was the one where both parents are together and are employed. The fourth family asked for additional help for the children still in school (there were four of them, and they would receive B$ 65 per child). However, the Baitulmal had not responded to the request at the time of the interview, several months after the request.

Interestingly, one of the families was continuously receiving aid for their children who were above 18 years old, which is the maximum eligible age limit. Sometimes, the families will also get non-regular help, such as coupons or royal rewards during festivals, but those are unreliable. Additionally, they received indirect assistance such as rent coverage, business lessons, and free hostels for their children who were in college, which were provided by several organizations such as BANTU and Yayasan.

Consumption

When comparing their overall income with the expenditures, respondents 2 and 4 say they do not have enough, family 3’s income and consumption were breakeven, and respondent 1 had surplus income. The extra money is saved though she notes that sometimes she has to spend them on medication. Of the two with inadequate income, respondent 2 explicitly says she does not have enough for basic needs, while respondent 4 does not go into detail. The third person is glad that she can help her husband with his debts but wishes she could start saving money.

All four families have implemented stringent yet simplified budgeting policies to deal with their issues, having varying priorities in everyday products but generally putting a high priority on giving their children access to quality education. According to respondent 1, “If the teacher asks him to buy, we have to buy because the school projects are included in their marks. If we do not buy, he will be scolded by the teacher. So we have to buy for school”. With that said, they receive assistance for school needs, as mentioned by respondent 3, and can typically afford most items necessary other than laptops. Concerning smartphones, only family 3 bought them for the children, and in the rest of the cases, they had to save pocket money to afford them, and not all children own a smartphone.

The analysis of the food that the families eat shows that their range of consumption is limited. Family 1 mostly eats rice pastries and instant noodles, and the children in family 3 consume rice and eggs with soy sauce. None of the children eat meat or vegetables often, and each respondent but the first mentions that their children dislike the latter. Family 2 often has its children skip breakfast, which consists of bread and water when it is available. Family 4 gives some of the children kiwi and limau juice, but only because it is necessary because of their genetic disorder. Overall, the nutritional needs of the children are likely unmet, particularly concerning vitamins. Parents appear to be unconcerned with their children’s nutrition despite the apparent concerns regarding it. The reason for this behavior is unknown, though likely causes are ignorance and a lack of resources.

Marginalized and Identity

Marginalization may be a notable problem that affects some family members who are not Bruneians but have Permanent Resident status because they were born in neighboring Malaysia or their father is a Malaysian. Respondent 2 said the following about her husband: “BANTU Services gave him a job but gave up because of what people said about him. He is Malaysian right? So the one helping him is Bruneians. Someone said to him, ‘Why are you the one who got the job even though you are Malaysian, [name]?’”.

Family 1’s children are Malaysian citizens and have to pay fees for passport renewal and school though they were born in Brunei and have lived in Brunei all their life. Additionally, Malaysians cannot apply for government housing unless they marry a Brunei citizen. This policy of excluding migrants or foreigners in their welfare system may be common around the world. However, there have been exceptions that are not present in Brunei. One of the respondents (family 1) discusses her daughter, the child of a Brunei citizen who has lived in the country for a considerable time but cannot be considered for housing welfare provisions. In the current circumstances, the lack of help provided to this population category, combined with their inability to leave due to poverty, perpetuates the issue.

Education and Employment

The last significant issue that has emerged throughout the interviews is the inability of the children to escape poverty. The reason is that, as mentioned by Cleary and Wong (2016), the pay in the private sector, which is more easily accessible to people with lower education, is much lower than that in the public professions. In addition to this high pay, the public sector also has strict requirements that involve getting O’Level qualifications in many subjects.

Poor people struggle to retake the tests if they fail them because the second attempt costs an unspecified amount of money, though they will repeatedly try: “That is why his only result is 1 ‘O.’ That is why he will take the exams again but paid exams. So we have the budget, he will take the exams again in the future”. Due to other factors that inhibit academic achievement, they ultimately struggle to reach a public position unless they have considerable talent or are lucky. As a result, they have to work in the private sector at low-level jobs, which are underpaid, which ultimately makes them poor in the capacity worldview as per Gweshengwe and Noor Hasharina Hassan (2019). As such, even if people put in significant effort, there are many obstacles to their success.

Housing Conditions

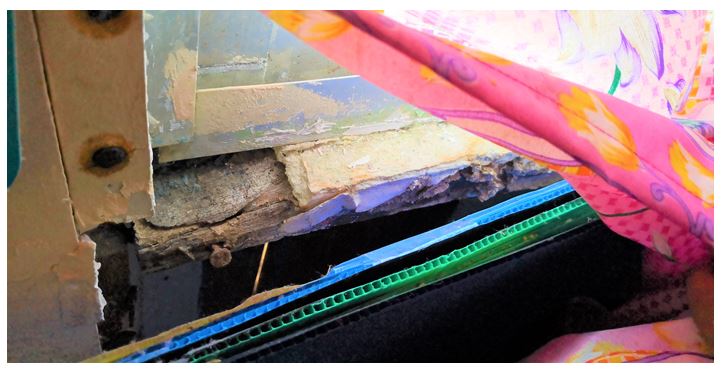

The observation of the house of participant 1 shows several problems. One issue is that there is not enough room in the house, with narrow walkways and overcrowded storage spaces.

Only three people live in the two-story house, but the available space is still limited, and much vertical stacking has to take place. With that said, some spaces are conspicuously empty despite sometimes having storage shelves there. The reason is that parts of the house are decaying, and in places, there are gaps in the wooden floors through which people or things can fall into the water below.

Overall, many parts of the house appear to be in a state of disrepair, and some of them are actively dangerous. In these conditions, it is difficult for children to have their private space to study and concentrate. Any repairs are makeshift and of uncertain quality, and a more skilled intervention is required.

Discussion

The Western view of poverty is based on the European and American perspectives of high urbanization and a robust private sector along with theories that may have been proven incorrect over time (Banerjee, Benabou, & Mookherjee, 2006). Brunei, which has a significant rural population and a significant disparity between the public and private fields, defies these expectations. The Western definition cannot be applied to the population of Kampong Ayer because though Brunei’s high GDP due to the income disparity of people in lower-income groups. Welfare money is likely distributed evenly between families in need regardless of their respective conditions.

However, families that are affected by poverty in Kampong Ayer likely find escaping it more challenging than their urban counterparts on land. When the respondents talked of higher education or occupations such as the police, they necessarily mention going elsewhere. Moreover, all three views on poverty that are listed by Gweshengwe and Noor Hasharina Hassan (2019) apply to the participants. They have low incomes, their expenditures are higher, and they struggle to escape their conditions. While their basic educational needs are mostly met in terms of resources, their food consumption warrants concern, the families mostly tend to rely on public transportation, and many of their children have to work in low-paid jobs to support the family. As such, a comprehensive approach that addresses all three types of issues is required to address the problem.

The exclusivity of the help is also problematic, as there is no unified system, the performance of various agencies differs, and special circumstances appear to be ignored. As such, people do not know where they can turn or what help they can receive. If the help they get is not enough, there is still nowhere else for them to turn, as the agencies in question have limited resources and may be either unable or unwilling to respond to some queries. Moreover, some of them appear to have lax checking procedures that enable people who do not qualify for aid to get it. Overall, the system is flawed and requires considerable improvements to achieve its goals.

Two of the participants were in broken families, living separate from their husbands and having poor relations with them. One chose to dissociate from the family after taking one of the three children while the other remained vindictive, refused to let his wife divorce him, and worked to obstruct her efforts to feed her children. Husbands that are present are helpful to the family’s finances, but there are still issues. In one case, the wife does not work, and in the other, the husband is in debt and has other issues that make his effective income lower than his wife’s. With that said, the dual-income family is the only one that does not rely on material assistance, which indicates that the model is likely helpful. Considering that extended family members appear to be irrelevant in the lives of all participants, this model appears to be the only viable one.

The families’ eating habits match the findings from Pakistan that are discussed by Malik et al. (2015). The families predominantly eat energy-rich foods, such as rice, with little meat or vegetables. This limited range of food consumption may lead to long-term issues, especially in the family that sometimes cannot afford breakfast. Two of the children in one family have a genetic disorder that makes them need to drink citrus juice, so the mother buys the fruits for them. However, this is a matter of necessity, and on the whole, the children’s nutritional needs are likely not met.

As a result of these issues, they may struggle academically, though their families put a high priority on ensuring that each child is educated. They lack the resources to ensure that their children’s education is as good as that of their peers. As a result, children from families that are affected by poverty will likely have worse average outcomes than the others. Additionally, they do not have the knowledge they need to feed their children appropriately and fail to recognize the harm that they cause. Overall, with the inability to buy the more expensive learning equipment and nutrition problems, the poverty of the family likely damages the child’s prospects.

Overall, as mentioned in the findings section, in Brunei, one has to be well-educated and socially networked to have a substantial chance to escape poverty because they have to qualify for a public position for better pay. Otherwise, poor young adults have to apply for unskilled or lower-paid positions in the private sector with little chance of advancement and struggle to maintain themselves. However, poverty is not responsible for their failure in the sense that they cannot buy the necessities. Even low-income families can afford essential school equipment or receive the aid necessary for their purchase. Instead, the principal problems are the various pressures of a poor and possibly discordant household and less noticeable factors, such as nutrition.

Because schools often struggle to perceive these problems due to their tendency to take place at home or not have an apparent cause, the children fall through the cracks’ of the system and are trapped in their financial position for life. Although education is nominally free, it will frequently require the students to supply some materials and penalize them if they fail to do so. Such items tend to be inexpensive, but to a low-income family, these expenses can be challenging to avoid. Over time, the various issues compound each other, and the outcomes of such children become below average, leading them to settle for lower-end jobs and fail to escape poverty in their generation.

Conclusion

Poverty in Kampong Ayer is not unique, but it is different from the Western conception of how the phenomenon takes place. The local opportunities are inadequate, and people move away rather than work to improve the conditions in the area. However, low-income families have barriers to doing so such as weaker educational outcomes and the pressure to support the family. Families in Kampong Ayer struggle to care for their children despite putting considerable effort into the task, and many of these children have to perpetuate the cycle. As such, this study recommends the Brunei government to attempt to create opportunities in Kampong Ayer or near it. Alternatively, it can expand welfare to address needs that are currently unmet, such as healthy food. In the future, researchers should try to consider the factors that hinder poor children’s education in more detail and try to develop healthier but still affordable diets to ensure that children can grow healthy.

References

Bach, M., & Morgan, M. S. (2019). Measuring difference? The United Nations’ shift from progress to poverty. History of Political Economy, 33(2), 26-30.

Banerjee, A. V., Benabou, R., & Mookherjee, D. (Eds.). (2006). Understanding poverty. Oxford University Press.

Bradshaw, J., Chzhen, Y., Main, G., Martorano, B., Menchini, L., & De Neubourg, C. (2012). Relative income poverty among children in rich countries. UNICEF Innocenti Research Center. Web.

Brando, N., & Schweiger, G. (eds.). (2019). Philosophy and child poverty: Reflections on the ethics and politics of poor children and their families. Springer.

Bucci, A., Prettner, K., & Prskawetz, A. (eds.). (2019). Human capital and economic growth: The impact of health, education and demographic change. Springer.

Bulman, D., Eden, M., & Nguyen, H. (2017). Transitioning from low-income growth to high-income growth: Is there a middle-income trap? Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 22(1), 5-28.

Chant, S. (2007). Poverty begins at home? Questioning some (mis) conceptions about children, poverty and privation in female-headed households. UNICEF. Web.

Chaudry, A., & Wimer, C. (2016). Poverty is not just an indicator: The relationship between income, poverty, and child well-being. Academic Pediatrics, 16(3), S23-S29.

Cleary, M., & Wong, S. Y. (2016). Oil, economic development and diversification in Brunei Darussalam. Springer.

Cobbinah, P. B., Erdiaw-Kwasie, M. O., & Amoateng, P. (2015). Rethinking sustainable development within the framework of poverty and urbanization in developing countries. Environmental Development, 13(3), 18-32.

Dayley, R. (2020). Southeast Asia in the new international era (8th ed.). Routledge.

Department of Statistics & Department of Economic Planning and Development (2018). Report of the household expenditure survey 2015/16.Ministry of Finance and Economy Brunei Darusallam. Web.

Gordon, D., Nandy, S., Pantazis, C., Townsend, P., & Pemberton, S. (2003). Child poverty in the developing world. Policy Press.

Gweshengwe, B. (2019). A critique of the Income Poverty Line and Global Multidimensional Poverty Index. Southeast Asia: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 19, 37-46.

Gweshengwe, B., & Noor Hasharina Hassan. (2019). Knowledge to policy: Understanding poverty to create policies that facilitate zero poverty in Brunei Darussalam. Southeast Asia: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 19, 95-104.

Gweshengwe, B., Noor Hasharina Hassan, & Hairuni Mohamed Ali Maricar. (2020). Perceptions of the language and meaning of poverty in Brunei Darussalam. Journal of Asian and African Studies. Advance online publication. Web.

Hair, N. L., Hanson, J. L., Wolfe, B. L., & Pollak, S. D. (2015). Association of child poverty, brain development, and academic achievement. JAMA Pediatrics, 169(9), 822-829.

Halim, A. R., Wahyudi, I., & Prasetyo, M. B. (2015). Pattern of consumption budget allocation by the poor families. Journal of Economics, Business, and Accountancy Ventura, 18(1), 47-64.

Hamilton, K., & Catterfall, M. (2007). Love and consumption in poor families headed by lone mothers. Advances in Consumer Research, 34, 559-564.

Hickel, J. (2016). The true extent of global poverty and hunger: Questioning the good news narrative of the Millennium Development Goals. Third World Quarterly, 37(5), 749-767.

Malik, S., Nazil, H., & Whitney, E. (2015). Food consumption patterns and implications for poverty reduction in Pakistan. The Pakistan Development Review, 54(4), 659-669.

McKeown, K., & Sweeney, J. (2001). Family well-being and family policy: A review of research on benefits and costs. Kieran McKeown Limited.

Neumayer, E., & Plumper, T. (2016). Inequalities of income and inequalities of longevity: A cross-country study. American Journal of Public Health, 106(1), 160-165.

Noor Hasharina Hassan (2017). Everyday Finance and Consumption in Brunei Darussalam. In V. T. King, Zawawi Ibrahim & Noor Hasharina Hassan (Eds.), Borneo Studies in History, Society and Culture. Springer.

Noor Hasharina Hassan, & Yong, G. Y. V. (2019). A vision where every family has basic shelter. In R. Holzhacker & D. Agussalim (Eds.), Sustainable development goals in Southeast Asia and ASEAN: National and regional approaches (pp. 190–209). Brill.

Osberg, L. (ed.). (2017) Economic inequality and poverty: International perspectives. Routledge.

Prydz, E., Jolliffe, D., Lakner, C., Mahler, D., & Sangraula, P. (2019). Global poverty monitoring technical note 8: National accounts data used in global poverty measurement. The World Bank.

Reinwick, N. (2011). Millennium Development Goal 1: Poverty, hunger and decent work in Southeast Asia. Third World Quarterly, 32(1), 65-85.

Rose Abdullah. (2012). Zakat management in Brunei Darussalam: Funding the economic activities of the poor. Sultan Sharif Ali Islamic University.

Sehrawat, M., & Giri, A. K. (2016). Financial development, poverty and rural-urban income inequality: Evidence from South Asian countries. Quality & Quantity, 50(2), 577-590.

World Bank. (2016). Monitoring global poverty: Report of the Commission on Global Poverty. World Bank Publications.

World Bank. (2018). Poverty and shared prosperity: Piecing together the poverty puzzle. World Bank Publications.

World Bank. (n.d.). GDP per capita (current US$) – Brunei Darussalam. Web.