Introduction

Throughout the 20th century’s second half, the explicitly and implicitly themes of feminism have been finding their way into children’s books to an ever larger degree. The reason for this is that one of the most notable discursive aspects of the historic period in question is that, throughout its entirety, the idea of women’s emancipation has been growing increasingly popular in the West. This simply could not be otherwise, because the ideals of gender egalitarianism, commonly associated with the notion of feminism, are indeed fully consistent with the overall logic of history.

Nevertheless, the adoption of ‘political correctness’ in just about every Western country (including Britain) by the late 1990s, as the governmentally endorsed social policy, resulted in the notion of feminism being deprived of its original aura of progressiveness. The reason for this is apparent – this specific development established the objective preconditions for the mentioned notion to grow increasingly distanced from the idea of gender equality, while becoming synonymous with the notion of mental and physical degeneracy, as something that has the value of a ‘thing in itself’. In its turn, this allows us to hypothesise that, when it comes to discussing the theme of women’s empowerment in the works of children’s literature, one must be capable of distinguishing the motifs of ‘emancipatory’ feminism from those of what can be defined as ‘pathological’ feminism. Whereas, the former is being concerned with the promotion of the idea that men and women are thoroughly equal, in the social sense of this word, and that they should treat each other with respect, the latter has to do with its advocates’ insistence that women are somehow ‘superior’ to men, and that the particulars of one’s gender-affiliation have nothing to do with the concerned person’s sense of self-identity (Nachescu 2009).

In my paper, I will explore the validity of this suggestion at length, in regards to the picture-book Piggybook by Anthony Browne and the novel The Illustrated Mum by Jacqueline Wilson (representing the examples of children’s literature in Britain), which clearly belong to two of the earlier outlined feminist writing-approaches. While addressing the task, I will argue that it is specifically Browne’s book, which does deserve to be recommended for reading by children, because as opposed to what it is being the case with The Illustrated Mum, it promotes the cause of the ‘emancipatory’ (socially beneficial) feminism.

The main qualitative features of children’s literature

Before proceeding to analyse the discursive significance of Piggybook and The Illustrated Mum, we will need to outline the qualitative features of children’s literature, in general. This has to be done, in order to define the degree of each of these books’ compliance with the methodological provisions of the genre in question. The main of these features can be defined as follows:

- The objective value of a particular children’s book is reflective of its ability to serve as the tool of ‘character education’, as defined by Arthur (2003). According to the author, “Character education can be understood to be a specific approach to moral or values education. Character is ultimately about who we are and who we become, good or bad. It constitutes an interlocked set of personal values” (p. 46). The reason for this is that children are naturally driven to assess the surrounding reality, and their place within it, in the value-based manner. However, given the fact that a child’s sense of the moral appropriateness/inappropriateness is essentially underdeveloped, it represents the matter of a crucial importance for writers to be able to ensure that, as a result of having been exposed to their books, children will be able to gain valuable clues, as to what accounts for the proper mode of addressing a particular challenge of life.

- A children’s book of value must provide young readers with the opportunity to interact (perceptually and cognitively) with whatever happen to be its actual subject matter. In this respect, we can only agree with Thomas, who pointed out that “reading is an interactive act” (1998, p. 138). There are a number of ways to have it accomplished. The main of them is adjusting the book’s themes and motifs to be consistent with the workings of a child’s psyche, and embellishing such a book with colourful illustrations, in order to ensure that young readers will indeed regard it; as such that represents a strong emotional appeal.

- By being introduced to a particular children’s book, young readers are expected to develop their skill of a dialectical reasoning, in the sense of being able to understand what accounts for the relationship between causes and effects, which in turn should contribute towards increasing the measure of these readers’ ‘quick mindedness’ (Fremantle 2006). The concerned activity is also anticipated to help children grow increasingly knowledgeable of the fact that the structure of written sentences has a strong effect of the actual messages that they convey. As Meek noted, while actively engaging with the book, children should become ever more aware of the fact that “words mean more than they say” (1988, p. 16). This, in turn, will come as a great asset, within the context of how young readers remain on the path of expanding their intellectual horizons.

- A children’s book must capable of keeping the targeted audience thoroughly entertained (McGillis 2009). The reason for this is apparent – as psychologists are being well aware of, the most effective way of ensuring that a child’s exposure to such literature will prove an educational asset of a high value, is establishing the objective prerequisites for the reading-process to be simultaneously both: experientially enjoyable and intellectually stimulating.

Piggybook by Anthony Browne

In light of the above-stated, Browne’s book can indeed be given much credit for meeting just about every of the mentioned criteria. After all, there can be only a few doubts that the author did succeed rather spectacularly, within the context of how he went about combining the elements of entertainment and education, in order to encourage readers to adopt a progressive outlook on what should be considered the role of women within the society. Browne also succeeded in helping children to recognise the sheer fallaciousness of the male-chauvinistic assumptions about the representatives of the ‘weak sex’, which continue to affect the existential attitudes of a great many men in the UK. What is particularly notable, in this respect, is that despite promoting the strongly defined idea of women’s social emancipation, Piggybook is the least concerned with trying to undermine the soundness of the traditional outlook on what is the actual purpose of the marital relationship between men and women, or with subjecting readers to any form of ideological indoctrination.

Browne’s approach towards encouraging young children to appreciate women (mothers), reflects his understanding of the fact that, in order for just about anyone to become emotionally comfortable with the idea in question, he or she must be prompted to perceive the alternative points of view, in this respect, as utterly unnatural (Meyer 2007). This helps to define the discursive significance of the book’s introductory lines, “Mr. Piggott lived with his two sons, Simon and Patrick, in a nice house with a nice garden, and a nice car in the nice garage. Inside the house was his wife” (Browne 1990, p. 1). Apparently, the author strived to prompt readers to realise that there is something utterly wrong with the manner, in which Mr. Piggot’s wife is being referred to, because the concerned referral implies her status having been that of a soulless commodity – much like that of the mentioned house and garage.

It is understood, of course, that there are strongly defined feminist overtones to the above-quoted, as it implies the sheer wrongness of the male-chauvinist practice of dehumanising women – even when it assumes the form of the seemingly ‘innocent’ patronisation of wives by their husbands. For example, prior to Mrs. Piggott’s ‘disappearance’, it would never occur to Mr. Piggott that there was anything wrong about his habit of using affectionate-diminutive words, when he needed to refer to her, “Hurry up with the meal, old girl” (Browne 1990, p. 5). Yet, the quoted referral implies that Mr. Piggott used to unconsciously believe that his wife was ‘inferior’ to him, because the word ‘old girl’ evokes the image of a woman, who despite being an adult, acts like a child.

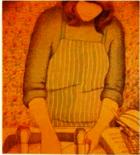

The format of picture-book provided Browne with yet additional opportunity to strengthen the emotional appeal of his subtle criticism of male chauvinism. This opportunity had to do with the fact that, just as it is being the case with the properly constructed rhetorical sentences; visual depictions are able to emanate a certain discursive ethos. For example, as it can be seen in the screenshots below, Mrs. Piggott is being depicted faceless, as she takes care of her domestic chores of a housewife.

This is meant to symbolise the fact that, metaphorically speaking, while having been treated by her husband and children as a servant, Mrs. Piggott was being slowly reduced to nothing short of an automaton, which does not have any personality, by definition. The chosen gamma of colours (brown and yellow-brown) accentuates the clearly defined pessimistic overtones of both pictures, as if implying that, while taking care of her husband and kids, Mrs. Piggott simply did not have any time to enjoy herself. There is, however, even more to it – Mrs. Piggott’s depiction as a faceless individual, implies that in Piggybook she acts as a ‘collective character’ – someone who embodies the anxieties of just about every housewife in this world. It is understood, of course, that this conveys a powerful message with the clearly defined feminist undertones to it – it is utterly arrogant, on the part of married men, to think of their wives in terms of ‘natural born’ servants.

Nevertheless, there is nothing truly innovative about this message. After all, it merely promotes the idea that the relationship between men and women should be harmonious – something of which the intellectually advanced individuals have been aware, throughout the history’s entirety (Barry, Chandler & Berg 2007). This again highlights the progressive sounding of Piggybook. As opposed to what it is being the case with the proponents of ‘radical feminism’, who believe that the representatives of two opposite sexes remain in the state of a perpetual war with each other, this book endorses the idea that, in order to be able to realise their full existential potential, men and women must be willing to cooperate.

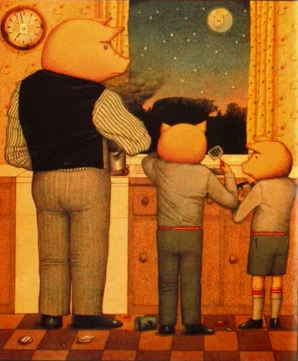

The book’s only motif, which appears to be formally related to this type of feminism, has to do with the contained implication that, when treating women disrespectfully, men in fact are being turned into pigs, in the allegorical sense of this word – hence, the discursive significance of the name Piggybook. The same can be said about the semiotic purpose of the book’s illustrations, which depict Mr. Piggott and two of his sons having undergone the transformation from humans into animals, such as the one seen below.

It will not require the application of any excessive effort to realise that this particular illustration evokes the notion of ‘sexist pig’, which is being commonly used by radical feminists, as a synonym of the notion of ‘male’. Yet, the book’s actual context makes this seemingly offensive aspect of how the author went about striving to educate children to be respectful of women, thoroughly justified. After all, it is not the particulars of the featured male-characters’ gender affiliation, which prompted Browne to consider that it will be fully appropriate, on his part, to accentuate their ‘piggishness’, but the fact that, prior to having been ‘abandoned’ by Mrs. Piggott, they did exhibit the essentially piggish behaviour.

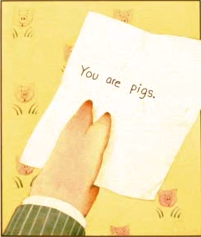

What is also particularly notable about how Browne have gone about exploring the theme of feminism in Piggybook, is the fact that, despite the author’s explicit and implicit criticism of the sexist prejudices towards women, he nevertheless could not help proving himself the affiliate of the patriarchal conceptualisation of the idea of womanhood. The validity of this suggestion can be shown, in regards to the illustration, which presents readers with the view of Mrs. Piggott’s note.

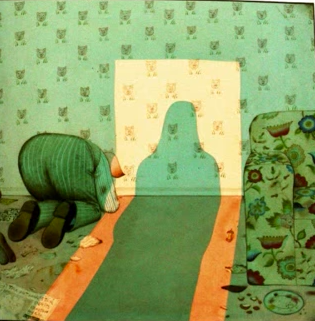

As it can be seen on the provided screenshot, Browne made a deliberate point in implying that the message, contained in this note, had an instantaneous effect on Mr. Piggott’s physical appearance, in the sense of turning him into a pig. In its turn, this can be interpreted as the indication of the author’s highly idealised view of women, as those who are being able to exert ‘magical’ powers over men. For just about anyone, familiar with the theory of psychoanalysis, there can be only a few doubts that this ‘knightly’ view of women, on Browne’s part, sublimates his deep-seated fear of them (Solomon 2004). After all, women are indeed well known for their ability to deprive men of what continues to allow the representatives of the ‘strong sex’ to enjoy the patriarchal dominance within the society – men’s aptitude in addressing life-challenges in the thoroughly rational/unemotional manner (Björn & Knights 2013). The validity of this statement can illustrated, in regards to what account for the psychological state of a man that has found himself fallen in love with a woman (Hancock 2007). Essentially the same line of argumentation can be applied, when it comes to discussing the significance of the book’s illustration, in which Mrs. Piggott is shown walking into the house.

After all, even a brief glance at this picture will reveal that it emanates the Freudian spirit of ‘uncanny’. As the father of psychoanalysis pointed out, “An uncanny experience occurs either when infantile complexes which have been repressed are once more revived by some impression, or when primitive beliefs which have been surmounted seem once more to be confirmed” (Freud 2003, p. 33). It is quite clear that the picture in question can be discussed as the visual sublimation of one’s archetypal fear of the unknown. The reason for this is that the shadow of Mrs. Piggott radiates both: strangeness (there is nothing ‘housewifey’ about it) and omnipotence (even though Mr. Piggott is shown simply bending over, readers get the impression that he in fact prays the shadow of his wife). Given the fact that archetypal anxieties in children are especially strong, after having been exposed to this picture, they would be naturally provided with the powerful (because it exists in the realm of the unconscious) incentive to regard women in terms of ‘authority figures’ – something that is being visualised by the picture below.

As readers learn at the end, the reason for Mrs. Piggott’s ‘mysterious’ absence had to do with her decision to mend the car in the garage, which given the story’s context, took the woman a long time. It goes without saying, of course, that the most plausible interpretation of this clearly feminist twist of the plot would be concerned with emphasising the fact that women are just as technically minded, as it happen to be the case with men (Jun 2012). The fact that Mrs. Piggott seems to have enjoyed herself, while addressing this essentially masculine task, confirms the validity of such our suggestion.

However, because Browne’s exploration of the theme of feminism has been undertaken from the position of a male, we can also speculate that this reflects the author’s lack of emotional comfort with the process of British men growing increasingly feminine, on one hand, and with the tendency of British women to become ever more masculine, on the other – at least, for as long as the existential attitudes of the latter are being concerned (Knights 2000). This, of course, implies that the book’s feminism-related themes and motifs are indeed socially relevant, because they appear to be thoroughly consistent with the qualitative aspects of a post-industrial living in Britain. Consequently, this provides us with yet another reason to suggest that Piggybook does have what it takes to be recommended for reading by children. In the aftermath of having been introduced to it, they will not only be able to learn to appreciate women, but also to gain a preliminary insight into the challenges of adulthood.

The Illustrated Mum by Jacqueline Wilson

As it was mentioned in the Introduction, there are a number of reasons to think that of Jacqueline Wilson’s novel The Illustrated Mum; as such that promotes the conventions of the ‘pathological’ (degenerative) form of feminism, reflective of its affiliates’ emotional discomfort with their gender-based identity.

To exemplify the soundness of this statement, we can refer to the character of Marigold, which in Wilson’s novel serves as the actual embodiment of the values of this type of feminism. The rationale behind this suggestion is quite apparent – throughout the novel’s entirety, Marigold never ceases to experience the elusive anxiety of not being able to relate to her self-identity of a woman and a mother. Marigold’s obsession with tattoos is perfectly illustrative, in this respect, “I love all my tattoos. They’re all so special to me. They make me feel special” (Wilson 1999, p. 13). Because most women do not experience any urge to cover their bodies with tattoos, in order to feel special, we can safely conclude that Marigold’s mental fixation on ‘body art’ was essentially pathological. After all, it remains a well-established fact among psychologists that one’s preoccupation with trying to accentuate its ‘uniqueness’, by the mean of altering its physical appearance to the extent that it would shock others, signifies that this person suffers from experiencing the unconscious sensation of self-loathing (Nicki 2001).

Wilson presents us with a number of additional proofs that this indeed must have been the case, the most notable of which are the novel’s implicit references to Marigold’s mental inadequacy, and to the fact that this character was addicted to drinking, “She (Marigold) drank her wine in less than half an hour and then said she felt a little sleepy… She fell asleep in the middle of a sentence” (Wilson 1999, p. 19). Yet, the author made a deliberate point in connecting these less than admirable qualities of Marigold to the idea that they are somehow reflective of the concerned character’s ‘feminist progressiveness’. The fact that this indeed happens to be the case can be illustrated, in regards to Marigold’s tendency to think of her decadent ways in terms of a social statement, “I don’t have to conform to your narrow view of society, Star. I’ve always lived my life on the outside edge” (Wilson 1999, p. 13). Moreover, the novel’s overall ethos implies that, despite Marigold’s lack of existential adequacy, she does deserve to be considered an intellectually liberated woman.

This alone makes it possible for us to suggest that the exploration of the theme of feminism in The Illustrated Mum is being concerned with the author’s strive to encourage readers to think of the notion of women’s empowerment, as such that has been triggered of the process of this country becoming increasingly ‘asexual’ – in full accordance with the provisions of political correctness. The most peculiar aspect of this process is that its agents tend to regard the indications of one’s mental/behavioural abnormality, as such that establish him or her as an intellectually sophisticate person. Thus, it will not be much of an exaggeration to suggest that, while working on her book, Wilson remained thoroughly observant of Watson’s suggestion that, contrary to the provisions of a commonsense logic, children’s writers must be socially irresponsible, “We need irresponsible writers if the prevailing complacencies of our age – however benevolent – are to be challenged…

Writers must be allowed to take risks…to be offensive… to challenge our most cherished assumptions about morality and the family” (1992, p. 6). Probably the main proof that this indeed must have been the case, can serve the fact that the way, in which the novel’s characters address life-challenges, presupposes their emotional detachment from British society, as a whole. In its turn, this prompts readers to think that there is indeed nothing wrong with one’s commitment (such as that of Marigold and Star) to exist in the socially alienated mode (Evans 2015). It is understood, of course, that this can hardly be considered as such that contributes to the literary value of Wilson’s novel.

There is even more to it – the novel in question contains many clues that the author’s feminist agenda is concerned with her intention to reassess the validity of the traditional outlook on what accounts for the relationship between a mother and a daughter. One of them is the fact that there are some rather suggestive overtones to Dolphin’s admiration of Marigold: “She (Marigold) was back. I (Dolphin) smelt her as soon as we opened the front door. Marigold’s sweet strong musky scent… ‘Oh Marigold,’ I said, and I flew at her” (Wilson 1999, p. 35). It may well be the case that some parents would not mind allowing their kids to be exposed to the literature, which endorses the unconventional views of what parenting is ought to be all about.

This, however, most definitely will not be the case with those parents who do not consider ‘irresponsibility’ to be the appropriate methodological approach to raising children.

There is another notable feature of the theme of feminism in The Illustrated Mom – the fact that, as it can be inferred from the novel, the issues that relate to the cause of women’s emancipation, have very little to do with the class-stratification of British society. For example, even though the novel’s female-characters of Marigold, Dolphin and Star appear to be socially disadvantaged in a variety of different ways, there is not even a single instance of them having suffered from a material hardship can be found in the novel. In fact, every time when the issue of shortage of money finds its way into the plot, the author is being quick enough to eliminate it out of sight, “Marigold: ‘You (Star) haven’t got any money’. Star: ‘Half my school hang out down there. I bet one of the boys will buy me a Coke and some French fries’” (Wilson 1999, p. 41).

The same can be said about the significance of the discussed book’s another important feature – the fact that, despite being shown as unconventional/rebellious individuals, Marigold, Dolphin and Star could not help turning such their rebelliousness into the mean of making the outwardly eccentric but essentially meaningless behavioural statements. To illustrate the validity of this statement, we can refer to the book’s ‘ice-cream eating scene’, “Marigold told us to open the fridge and there it was simply stuffed with ice cream… We ate Cornettos and Mars and Soleros and Magnums, one after another after another, and then when they all started to melt Star mixed them all up in the washing-up bowl and said it was ice cream soup” (Wilson 1999, p. 39). After all, the mentioned scene is indeed being fully consistent with the tendency of ‘pathological’ feminists to do just about anything, in order to prove themselves utterly ‘progressive’ – even at the expense of indulging in behaviour that can hardly be considered socially/mentally appropriate.

This once again points out to the fact that the manner, in which the theme of feminism is being explored in The Illustrated Mum, does not quite correlate with that of ‘classical’ feminist writers, such as Kate Chopin, for example. The reason for this is apparent – the discursive premise of Wilson’s novel does not take into account the socio-economic factors of influence, within the context of how many British women struggle with the legacy of patriarchialism. In its turn, this undermines the educational value of The Illustrated Mom, as a children’s novel.

Conclusion

In light of the earlier outlined qualitative specifics of children’s literature, it appears that it is namely Browne’s Piggybook, which should be deemed fully consistent with the genre’s provisions. The main reason for this is that the reading of this particular book by children will not only teach them to respect women, but also to understand what predetermines the appropriateness of such of their would-be behaviour. The same, however, cannot be said about Wilson’s novel The Illustrated Mum, as a literary work that establishes parallels between the ideals of gender egalitarianism, on one hand, and some women’s tendency to exhibit a psychologically deviant behaviour, on the other. Apparently, it never occurred to Wilson that by challenging the traditional assumptions about morality/facility, she in fact contributed to the process of the integrity of British society being undermined from within. The irony here is concerned with the fact that is that this appears to be the main reason why The Illustrated Mum ended up being critically acclaimed, in the first place.

I believe that this conclusion confirms the validity of the paper’s initial thesis that, even though the theme of feminism does define the semiotics of many modern works of children’s literature in Britain, it is important to be able to understand what account for the qualitative subtleties of this theme’s presentation in each of these works.

References

Arthur, J 2003, ‘Character education in British education policy’, Journal of Research in Character Education, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 45-58.

Barry, J, Chandler, J & Berg, E 2007, ‘Women’s movements: abeyant or still on the move?’, Equal Opportunities International, vol. 26, no. 4, pp. 352-369.

Björn, R & Knights, D 2013, ‘Open innovation, gender and the infiltration of masculine discourses’, International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 275-297.

Browne, A 1990, Piggybook, Dragonfly Books, London.

Evans, M 2015, ‘Feminism and the implications of austerity’, Feminist Review, , no. 109, pp. 146-155.

Fremantle, S 2006, ‘The power of the picture book’, in P Pinsent (ed), The power of the page, David Fulton, London, pp. 6-13.

Hancock, T 2007, ‘The chemistry of love poetry’, Cambridge Quarterly, vol. 36, no. 3, pp. 197-228.

Jun, Z 2012, ‘Gender identity and language usages in masculine-feminine discourse’, GSTF Journal of Law and Social Sciences (JLSS), vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 201-208.

Knights, D 2000, ‘Unmasking the masculine: “men” and “identity” in a sceptical age’, Human Relations, vol. 53, no. 8, pp. 1099-1105.

McGillis, R 2009, ‘What is children’s literature?’, Children’s Literature, vol. 37, pp. 256-262.

Meek, M 1988, How texts teach what readers learn, Thimble Press, London.

Meyer, A. 2007, ‘The moral rhetoric of childhood’, Childhood, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 85-104.

Nachescu, V 2009, ‘Radical feminism and the nation: history and space in the political imagination of second-wave feminism”, Journal for the Study of Radicalism, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 29-59.

Nicki, A 2001, ‘The abused mind: feminist theory, psychiatric disability, and trauma’, Hypatia, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 80-104.

Salleh, A 2003, ‘Ecofeminism as sociology’, Capitalism, Nature, Socialism, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 61-74.

Solomon, B 2004, ‘Psychoanalysis and feminism: a personal journey’, The Annual of Psychoanalysis, vol. 32, pp. 149-160.

Thomas, H 1998, Reading and responding to fiction: classroom strategies for developing literacy, Scholastic, London.

Watson, V 1992, ‘Irresponsible writers and responsible readers’, in M Styles et al. (eds). After Alice: exploring children’s literature, Cassell, London, pp. 1-8.

Wilson, J 1999, The illustrated mum, Doubleday, London.